Surgical treatment of bronchiectasis: a retrospective observational study of 138 patients

Introduction

Bronchiectasis is defined as permanent dilatations of bronchi with destruction of the bronchial wall. Bronchiectasis was first described by Laenec in 1819 and, before the antibiotic era, was considered a morbid disease with a high mortality rate from respiratory failure and cor pulmonale (1). The clinical picture varies greatly and may involve repeated respiratory infections alternating with asymptomatic periods or with chronic production of sputum. Bronchiectasis should be suspected especially when there has been no exposure to tobacco smoke. The sputum may be bloody or hemoptysis might be recurrent (2).

Today, with the improvement of health care and the availability of suitable antibiotics, the prevalence of bronchiectasis has declined and the patients with early disease can be treated successfully by conservative procedures in developed countries. Bronchiectasis still constitutes an important problem in developing countries because of tuberculosis, pneumonia, pertussis and serious rubeola infections (3). Current reports about the surgical management for bronchiectasis show that limited localized disease was associated with good postoperative prognosis (4).

The aim of this study was to analyze the cases of bronchiactesis in our tertiary referral hospital; its presentation, etiology, diagnostic tools, indications for surgery, surgical approach, and the outcome.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 138 patients who underwent surgical resection for bronchiectasis between March 2003 and March 2010, at the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery in Mansoura University Hospital. Variables of age, sex, symptoms, etiology of bronchiectasis, lobe involved, inductions and types of surgery, mortality, morbidity and the result of surgical therapy were analyzed. All patients with bronchiectasis were included in the study except patients with bronchial adenomas.

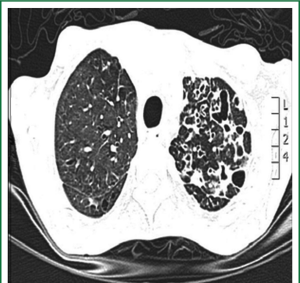

Patients were admitted to the department from either the chest disease department or our outpatient clinic as a referral from another chest hospitals. Chest radiography (CXR), computed tomography of the chest (CT) to evaluate the type, severity, and distribution of bronchiectasis (Figure 1) and pulmonary function tests were carried out for selected patients. All patients had intensive chest physiotherapy in the preoperative period. Sputum culture and sensitivity tests of all patients were examined and prophylactic antibiotics were given accordingly. Chest physiotherapy was continued until the daily volume of the sputum decreased to 50 mL or less. Rigid and/or flexible bronchoscope was performed for all patients for the removal of secretion and determining foreign body or endobronchial lesions. The bronchial aspirate was sent for microbiologic culture analysis. Prophylactic antibiotics were given for 48 hours prior to surgery to prepare all patients undergoing surgery.

Surgical treatment was considered if the symptoms persisted in spite of several courses of treatments and if the extent of diseased lung to justify operations is localized to achieve complete resection. Non surgical treatments included appropriate antibiotic therapy, postural drainage, and possibly bronchodilators. The persisting symptoms justifying operations were recurrent pneumonia that requires hospitalization and recurrent significant hemoptysis.

A double-lumen endotracheal tube was used in order to avoid contralateral contamination of secretions. A posterolateral thoracotomy was used for all patients. Complete resection is defined as an anatomic resection of all affected segments that were assessed preoperatively by computed tomography. If the disease is limited to one lobe, lobectomy was done and when the whole lung was affected, pneumonectomy was performed. When the disease is fairly limited, segmentectomy was performed. During pulmonary resection, excessive bronchial dissection was avoided, and peribronchial tissues were preserved. The bronchial stump was closed by using a polypropylene suture in two layers. Usually, we use a flap of mediastinal pleura or tissue for covering the bronchial stump. All resected specimens were subjected to histo-pathological examination in order to confirm the diagnosis.

Postoperative management included intensive chest physiotherapy and administration of antibiotics and analgesics. Operative mortality included patients who died within 30 days after thoracotomy or those who died later but during the same hospitalization. All patients were followed up in our outpatient clinic.

Statistical analysis

All data were stored using SPSS 16.05 for Windows. Quantitative variables were compared by t test and qualitative variables by chi-square test. A value of P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

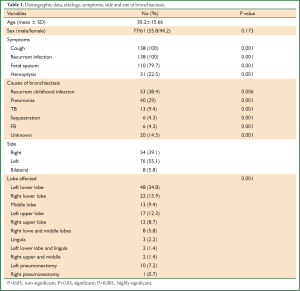

A total of 138 patients underwent surgical treatment of bronchiectasis in our department in the study period. The mean age of these patients was 30.2±15.7. Male to female ratio was 77/61 where 55.8% of patients were male but it was not statistically significant.

All patients were symptomatic. The most common presenting symptom was recurrent infection with productive cough where it occurred in all patients. Copious amount of fetid sputum was found in 110 (79.7%) patients and recurrent hemoptysis was found in 31 (22.5%) patients. The duration of symptoms ranged from one to 9 years (mean of 3.7±2.3 years). The possible etiologies of bronchiectasis were listed in Table 1.

Full Table

Postero-anterior and lateral chest roentgenographs and CT scan were done for all patients, but the diagnosis of bronchiectasis was based mainly on the chest CT scan finding. It determines the type and extent of bronchiectasis. Rigid and/or flexible bronchoscope was performed for all. The disease was on left side in 76 (55.1%) patients and in the right side in 54 (39.1%). The disease was bilateral in 8 (5.8%) patients. Bronchiectasis involvement was predominantly in the lower lobes. The left lower lobe was affected in 48 (34.8%) patients and right lower lobe in 22 (15.9%).

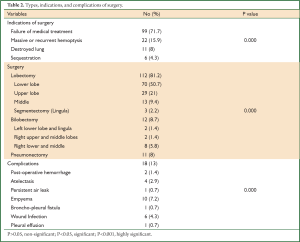

The indications for pulmonary resection were failure of medical therapy in 99 (71.7%) patients, recurrent or massive hemoptysis in 22 (15.9%), destroyed lung in 11 (8%), and sequestration in 6 (4.3%). Posterolateral thoracotomy and complete resection of all diseased segments were performed in all patients except in patients with bilateral disease. A hundred and twelve patients (81.2%) had a lobectomy, 12 (8.7%) patients had a bilobectomy, 3 (2.2%) patients had segmentectomy (lingulectomy), and 11 (8%) patients had a pneumonectomy (Table 2).

Full Table

Complications occurred in 18 (13%) patients and included postoperative bleeding that required exploration in 2 (1.4%) patients, atelectasis requiring bronchoscope in 4 (2.9%) patients, a persistent air leak (more than 7 days) in one (0.7%) patient and this patient was proved to have bronchopleural fistula later on, empyema in 10 (7.2%) patients, wound infection in 6 (4.3%) patients, and pleural effusion in one (0.7%) patient.

Follow-up data were obtained for 120 (87%) of the patients. The mean follow-up of these patients was 2.1±1 years (range from 1 to 4 years). The symptoms disappeared in 101 (84.2%) patients and 19 (15.8%) patients showed residual symptoms. During the follow up period, three patients developed recurrent hemoptysis. Completion pneumonectomy was done after one year for one patient and 2 years for the other two. Right lower lobectomy was done for one of the patients for whom middle lobectomy was done because of frequent re-admission due to recurrent chest infection and hemoptysis.

Discussion

Bronchiectasis is pathologically defined as a condition in which there are abnormal and permanent dilatations of proximal bronchi (1,3,5). It is defined on a pathological basis of different etiologies ending in bronchiectatic changes such as tuberculosis and sequestration (1,2,6,7). Before the antibiotic era the disease was considered a morbid one with a high mortality rate from respiratory failure and cor pulmonale (3,5). It is usually caused by pulmonary infections or bronchial obstruction (3,4). The incidence of bronchiectasis is unknown (3,5). The prevalence of bronchiectasis decreased significantly over recent decades due to the proper use of antimicrobial therapy and immunization against viral and bacterial agents. Early recognition of foreign bodies with bronchoscopy also decreased the incidence of post-obstructive bronchiectasis (8). However, the incidence of bronchiectasis is still high in developing countries (8,9). In spite of the advances in thoracic surgery, the optimal treatment for bronchiectasis remains controversial (10).

Vendell and colleagues reported different causes of bronchiectasis including post infection, bronchial obstruction, immune deficiency, impaired mucocilinary clearance, inflammatory pneumonitis, structural airways abnormalities and association with other disease (2). They also reported that the cause remains unknown in a fairly high percentage of patients ranging from 26% to 53% (2,11). Recurrent pulmonary infection or pneumonia either in childhood or adulthood (67.4%) was the most common cause in our patients followed by pulmonary tuberculosis in (9.4%) of patients and pulmonary sequestration and foreign body obstruction in (4.3%) of patients for each. Unknown etiology was reported in (14.5%) of patients. In our study, there was mix of etiologies because the number in each category is not enough for statistical sampling (1,6,7,12).

Patients with bronchiectasis typically present with recurrent pulmonary infections, productive cough, bronchial suppuration and purulent bronchorrhea (1,13). Similar to our series, cough, purulent and fetid sputum, and hemoptysis are the most common symptoms in other series (1,6,10,13).

Diagnosis of bronchiectasis is based on clinical history and CT scan findings (1,2,14). All the patients in our study had CT scan. CT criteria for diagnosis of bronchiectasis are well established (internal diameter of the bronchus more than 1.5 times than that of accompanying artery and evidence of lack of tapering of bronchi) (2,14). Bronchoscopy is not a main diagnostic method for bronchiectasis, but it may be helpful in identifying and removing foreign bodies, for locating the site of bleeding in patients with hemoptysis, and for diagnosing narrowed bronchi or neoplasms (3,6,8,9,12,15). Preoperative bronchoscopy should be routinely done to rule out benign or malignant cause of obstruction (3,15). In our study, rigid and/or fiber-optic bronchoscopy was performed for all patients for the above mentioned reasons in addition to preoperative cleaning of the tracheobronchial tree in preparation of the selected patients for surgery.

In general, bronchiectasis affects most dependent portions of the lung, which includes posterior basal portions of the lower lobes, middle lobe and lingula. Overall one third of bronchiectasis is unilateral and affects a single lobe, one third is unilateral but affects more than one lobe, and one third is bilateral (1,10). In our series, the disease affected the left lung in 76 (55.1%) of patients. It was mainly confined to the lower lobes either alone in 70 (50.7%) of patients or in conjunction with middle lobe or lingual in 10 (7.2%) of patients.

The initial treatment strategy for all patients with this disease should be conservative. Infection control, bronchodilatation and chest physiotherapy (postural drainage) are the main components of conservative treatment. If medical treatment is unsuccessful or frequent episodes of hemoptysis exist surgical therapy should be considered (1,3,16-18). As was the case with other series (3,4,6,12,14-17), the indications for surgery in our study were failure of medical therapy, recurrent or massive hemoptysis, destroyed lung, and sequestration.

The goals of surgical therapy for bronchiectasis are to improve the quality of life and to resolve complications such as empyema, severe or recurrent hemoptysis, and lung abscess. There is also consensus that, because bronchiectasis is a progressive disease, affected regions should be resected in a way that preserves uninvolved lung parenchyma, and early pulmonary resection while the disease is still localized is preferred (3,6,9,10,12,16-19). Complete and anatomical resection should be done with preservation of as much lung function as possible in order to avoid cardiorespiratory restriction. Therefore every type of resection is possible for these purposes. Ultimately, a minimum of two lobes or six pulmonary segments must be spared to ensure adequate pulmonary function (1,14,16,20,21). For successful surgery, Kutly and colleagues recommend that the operation should be performed in ‘dry period’, complete resection of suspected areas by intraoperative examination that could not be determined by radiological examination to decrease relapse rates, and surgical treatment in childhood because the residual lung could still grow to fill the space left in the chest after resection (10).

Apart from the eleven patients who underwent pneumonectomy for destroyed lung, most of our patients had a localized disease to one or more lobe. Complete resection was achieved in 130 (94.2%) of patients. Bilateral bronchiectasis does not present a contraindication to surgical therapy in selected patients (3,7,10). In our series, eight (5.8%) patients had bilateral bronchiectasis. A staged thoracotomy for these patients was performed.

Complication occurrence is 9.4-24.6% in the current literature, therefore our result of (13%) is within the reported incidence (3,4,7,10,12,14,15,21,22). It included early and late complications. Early complications included bleeding requiring exploration, empyema, and prolonged air leak more than 7 days… and the late one included the recurrence of symptoms and extension into other lobes or segments. There was no reported any postoperative arrhythmias. Apart from the patient developed bronchopleural fistula, all complications were successfully treated. That patient developed empyema with persistent air leak and was proved to have bronchopleural fistula. He was re-admitted 8 months after surgery with persistent air space, recurrent empyema, and chest infection. He was proved to have open tuberculosis and his clinical condition deteriorated. Mortality ranges from 0% to 8.3% in the literature and current mortality is less than 1% (10,12,15). There was no operative mortality in our series.

In our study, patients with complete resection of a localized bronchiectasis had better outcomes than those with incomplete resection. Regarding symptoms, the results of surgery can be considered satisfactory in our experience. More than 84% of our patients had relieved their preoperative symptoms. These results are similar to other series (1,6,7,10,12,14,15,22).

The follow up time was short as we depend mainly on the outpatient department visits. Follow up data were obtained from (87%) of the patients and the others lost to follow up. Our center is a referral center that covers a wide area and most of the patients with improvement of symptoms lost to follow up as they are far from the center and their concept that they need no more follow up.

In conclusion, surgical resection of bronchiectasis can be performed with acceptable morbidity and mortality at any age for localized disease. Proper selection and preparation of the patients and complete resection of the involved sites are required for the optimum control of symptoms and better outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the staff of cardiothoracic surgery department at Mansoura University Hospital for their assistance and support in conducting this research.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Balkanli K, Genç O, Dakak M, et al. Surgical management of bronchiectasis: analysis and short-term results in 238 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003;24:699-702. [PubMed]

- Vendrell M, de Gracia J, Olveira C, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of bronchiectasis. Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery. Arch Bronconeumol 2008;44:629-40. [PubMed]

- Agasthian T, Deschamps C, Trastek VF, et al. Surgical management of bronchiectasis. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62:976-8. [PubMed]

- Ashour M, Al-Kattan K, Rafay MA, et al. Current surgical therapy for bronchiectasis. World J Surg 1999;23:1096-104. [PubMed]

- Seaton D. Bronchiectasis. In: Seaton A, Seaton D. eds. Crofton and Douglas’s respiratory diseases. Volume I. 5th ed. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000:794-808.

- Prieto D, Bernardo J, Matos MJ, et al. Surgery for bronchiectasis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:19-23, discussion 23-4. [PubMed]

- Sehitogullari A, Bilici S, Sayir F, et al. A long-term study assessing the factors influencing survival and morbidity in the surgical management of bronchiectasis. J Cardiothorac Surg 2011;6:161. [PubMed]

- Campbell DN, Lilly JR. The changing spectrum of pulmonary operations in infants and children. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1982;83:680-5. [PubMed]

- Otgün I, Karnak I, Tanyel FC, et al. Surgical treatment of bronchiectasis in children. J Pediatr Surg 2004;39:1532-6. [PubMed]

- Kutlay H, Cangir AK, Enön S, et al. Surgical treatment in bronchiectasis: analysis of 166 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;21:634-7. [PubMed]

- Pasteur MC, Helliwell SM, Houghton SJ, et al. An investigation into causative factors in patients with bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;162:1277-84. [PubMed]

- Yuncu G, Ceylan KC, Sevinc S, et al. Functional results of surgical treatment of bronchiectasis in a developing country. Arch Bronconeumol 2006;42:183-8. [PubMed]

- Deslauries J, Goulet S, Franc B. Surgical treatment of bronchiectasis and broncholithiasis. In: Franco LF, Putnam JB. eds. Advanced therapy in thoracic surgery. Hamilton, ON: Decker; 1998:300-9.

- Giovannetti R, Alifano M, Stefani A, et al. Surgical treatment of bronchiectasis: early and long-term results. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2008;7:609-12. [PubMed]

- Fujimoto T, Hillejan L, Stamatis G. Current strategy for surgical management of bronchiectasis. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:1711-5. [PubMed]

- Neves PC, Guerra M, Ponce P, et al. Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011;13:619-25. [PubMed]

- Sanderson JM, Kennedy MC, Johnson MF, et al. Bronchiectasis: results of surgical and conservative management. A review of 393 cases. Thorax 1974;29:407-16. [PubMed]

- Stephen T, Thankachen R, Madhu AP, et al. Surgical results in bronchiectasis: analysis of 149 patients. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2007;15:290-6. [PubMed]

- De Dominicis F, Andréjak C, Monconduit J, et al. Surgery for bronchiectasis. Rev Pneumol Clin 2012;68:91-100. [PubMed]

- Laros CD, Van den Bosch JM, Westermann CJ, et al. Resection of more than 10 lung segments. A 30-year survey of 30 bronchiectatic patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1988;95:119-23. [PubMed]

- Sirmali M, Karasu S, Türüt H, et al. Srgical management of bronchiectasis in childhood. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;31:120-3. [PubMed]

- Al-Kattan KM, Essa MA, Hajjar WM, et al. Srgical results for bronchiectasis based on hemodynamic (functional and morphologic) classification. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;130:1385-90. [PubMed]