One successful primary closure case of bronchopleural fistula after pneumonectomy by a new method

Introduction

A bronchopleural fistula (BPF) is a cavity that develops between the bronchial tree and the pleural space. It is estimated that the incidence of BPF after pneumonectomy for lung cancer is 4.5–20% (1). It is a severe complication after pneumonectomy and carries a high mortality rate, ranging from 25% to 67% (2,3). The etiology of BPF includes incomplete tumor resection, use of steroids, intraoperative infection and prolonged postoperative mechanical ventilation as major risk factors of BPF (1). The clinical manifestations of BPF can be frequently classified as acute, subacute, or chronic. An acute BPF presents as tension pneumothorax, with the pleural cavity communicating abnormally with the airways, and is associated with purulent sputum expectoration, dyspnea, and reduction in established pleural effusion (3). The management of this serious postoperative complication remains a challenge. Therapeutic options range from extensive surgical procedures, including a repeat thoracotomy, thoracoplasty, or chest-wall fenestration. Traditional treatments of BPF include thoracotomy after drainage and primary repair, which is based on vascularized muscular flaps and omental grafts tissues (4). Closure of a fistula using endoscopy constitutes a therapeutic alternative, and major surgery can be avoided. The use of fibrin glue has been recommended for closure of BPFs smaller than 3 mm (5), and there are a few recommendations of using a fibrin gluecoated collagen patch for closure of BPFs (6). Thus, although a wide variety of bronchoscopic procedures have been developed recently, no gold standard has yet been established regarding the treatment of choice. Herein, we report one case of successful closure of a BPF by sealing from both inside the chest cavity and bronchus, and so far there is no such case reported before.

Case presentation

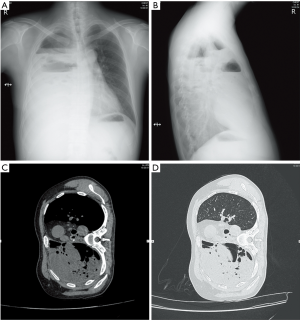

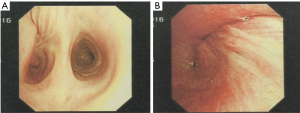

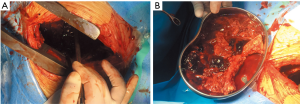

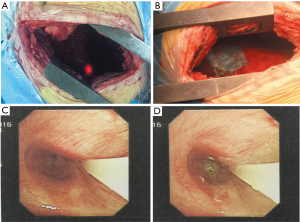

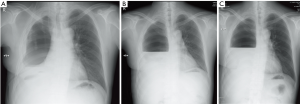

A 47-year-old male patient, who had short of breath and chest distress for 1 week and was found to have a mass in the chest cavity 5 years ago. Chest DR and CT scan (Figure 1) showed a huge cystic space-occupying lesion in the right chest cavity and the right lung was completely compressed. Diagnosis before surgery was considered as teratoma. The cyst located in the right pleural cavity occupied most of the cavity. Cyst resection was planned and severe adhesion (Figure 2A) to chest wall and right lung was found during the operation. About 3,000 mL of brown and nepheloid liquid was extracted from the cyst. Most of the right visceral pleura were cut off because of serious adhesion. The right lung was completely compressed and atelectatic with severe air leakage when the cyst was completely resected, so a right pneumonectomy was made to prevent pyothorax and further complications. The cyst is about 30 cm × 20 cm in size (Figure 2B,C), and pathological diagnosis confirmed simple cyst. The patient was discharged on postoperative day (POD) 6 with anemia and hypoproteinemia because of personal reasons and was readmitted on POD 20 for serious cough with plenty kermesinus begma. At the time of admission, the patient had WBC 3,190/mL, ALB 3.4 g/dL, HBG 80g/L, height 171 cm, weight 55.7 kg, heart rate 87/min, blood pressure 122/66 mmHg, temperature 36.5°C, and SpO2 97%. BPF was suspected and radioscopy revealed air and multiple encapsulated effusion in the right chest cavity with no obvious fistula was found between bronchial stump and chest cavity (Figure 3). The effusion was encapsulated and partly organized, so a thoracotomy was planned to clean up the right cavity because it was hard to find an appropriate position to take close drainage. Bronchoscopy was performed before surgery and kermesinus liquid was found flowing from the bronchial stump (Figure 4). There was plenty of kermesinus pleural effusion in the chest cavity with some blood coagulum (Figure 5). Defect lack oxygen bacterium was found from the bacterial culture of the effusion. After cleaning up the effusion and coagulum, thick pleural fibrous membranes were found without visible fistula. No air leakage was found during thoracic washing, but a bright spot (Figure 6A) could be seen when the bronchoscope was inserted to bronchial stump, so medical anastomotic glue (OB Glue) was smeared to the spot and covered with NEOVEIL (Gunze Co., Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 6B). Meanwhile OB Glue (Gzbme Co., Guangzhou, China) was emitted to the bronchial stump by bronchoscope (Figure 6C,D). Closed drainage was made after the operation. The patient recovered well after the treatment, repeat bacterial culture was negative, and the patient was discharged on POD 7.

Discussion

BPF is defined as an abnormal communication between a lobar or the main bronchus and the pleural space, and continues to be a severe surgery complication, which is related to high morbidity and mortality (7). Risk factors associated with BPF incidence are technical errors, anemia, hypoproteinemia, steroid use, etc. (8). Anemia and hypoproteinemia resulted an undesirable healing leading to a BPF after right pneumonectomy to this patient. Hemoglobin was 63 g/L and ALB was 26.5 g/L when the patient was discharged from the hospital. Clinical manifestations of BPF after pneumonectomy can present as cough, purulent sputum expectoration, and reduction in established pleural effusion, fever, leukocytosis, etc. Kanakis et al. (9) reported patients presenting with a sudden drop in the pleural fluid level after a pneumonectomy in the absence of a recognizable BPF have been classified as cases of benign emptying of the post-pneumonectomy space (BEPS). The study identified four cases in 1,378 pneumonectomies of BEPS (0.29%). Although BEPS is an extremely rare complication, early recognition and close patient monitoring will prevent unnecessary interventional strategies. Although this patient was recognized as having a BPF on POD 20 by obvious manifestations and bronchoscope examination, there were no infectious symptoms, the WBC test and temperature were normal or it could be thought in earlier stage of BPF. The CT scan showed the effusion was encapsulated and partly organized, so a thoracotomy was planned to clean up the right cavity and take close drainage because it was hard to find an appropriate position to take close drainage by CT scan. After the effusion was cleaned up, no visible fistula was found, even though it was difficult to find the bronchial stump which was identified by the bright spot from the bronchoscope. The medical anastomotic glue used in this case had a much better adhesion compared to fibrin glues, and the NEOVEIL patch is absorbable which can prevent infection and rejection. For this patient, by sealing from both inside the chest cavity and the bronchus, it received better results compared to single sealing through endoscopy.

The patient recovered well and follow-up radiograph showed normal clinical manifestation after pneumonectomy in follow-up for over one month (Figure 7).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the case reported here indicates that sealing from both inside the chest cavity and bronchus is applicable as a therapeutic option, at least for BFS patients with low diameter size and in earlier stage. The described procedure is simple, safe, and effective for BPF patients.

Acknowledgements

We thank Amanda Khuong for assistance with paper editing and revision of wording and grammar at Stanford.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

References

- Shekar K, Foot C, Fraser J, et al. Bronchopleural fistula: an update for intensivists. J Crit Care 2010;25:47-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cerfolio RJ. The incidence, etiology, and prevention of postresectional bronchopleural fistula. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;13:3-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lois M, Noppen M. Bronchopleural fistulas: an overview of the problem with special focus on endoscopic management. Chest 2005;128:3955-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kramer MR, Peled N, Shitrit D, et al. Use of Amplatzer device for endobronchial closure of bronchopleural fistulas. Chest 2008;133:1481-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nagahiro I, Aoe M, Sano Y, et al. Bronchopleural fistula after lobectomy for lung cancer. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2007;15:45-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takanami I. Closure of a bronchopleural fistula using a fibrin-glue coated collagen patch. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2003;2:387-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamid UI, Jones JM. Closure of a bronchopleural fistula using glue. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2011;13:117-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chawla RK, Madan A, Bhardwaj PK, et al. Bronchoscopic management of bronchopleural fistula with intrabronchial instillation of glue (N-butyl cyanoacrylate). Lung India 2012;29:11-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanakis MA, Misthos PA, Tsimpinos MD, et al. Benign emptying of the post-pneumonectomy space: recognizing this rare complication retrospectively. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2015;21:685-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]