The safety profile of preoperative administration of heparin for thromboprophylaxis in Chinese patients intended for thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery: a pilot randomized controlled study

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), mainly consisting of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is the third commonest cause of cardiovascular death after myocardial infarction and stroke with high morbidity and mortality (1,2). Patients who underwent major thoracic surgery including lobectomy, pneumonectomy, esophagectomy are often at a higher risk for VTE (3). The incidence of VTE for patients following major thoracic surgery was estimated to be as high as 19–26% (4). Even though American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines recommended routine VTE prophylaxis with either heparin sodium (unfractionated heparin) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for those high risk patients after thoracic surgery, the rational timing and dose of heparin thromboprophylaxis is still lack of consensus (5,6). Recent researchers have found that even though patients who underwent thoracic surgery received thromboprophylaxis postoperatively there was still chance of VTE after thoracic surgery (7,8). Therefore, some investigators have raised the doubt that whether postoperative heparin once or twice a day could provide sufficient thromboprophylaxis for patients following major thoracic surgery (5). Moreover, many patients underwent major thoracic surgery for cancer, and cancer patients were reported to be about 5- to 7-fold higher risk of VTE compared with normal population (9). Cancer patients were also found to be more than threefold of risk of fatal PE than non-cancer patients undergoing similar thoracic surgery (10). Therefore, there is an urgent need for investigating the rational timing and dose of heparin for thromboprophylaxis in patients intended for thoracic surgery. Due to the special medical conditions in China, patients intended for thoracic surgery usually need an average preoperative time of 3–5 days for surgery preparation after hospital admission, not the same as those in western countries who undergo surgery at the day of admission, and different human races have different risks of DVT, which indicated a need of specific plan of thromboprophylaxis for Chinese patients. Since American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines recommended starting heparin as thromboprophylaxis of orthopedic surgery 12 h or more preoperatively (11), we therefore believe that preoperative administration of heparin for thromboprophylaxis in major thoracic surgery is still reasonable and safe. As there is no relevant study available, we conducted this pilot randomized controlled trial to explore the safety profile of preoperative administration of heparin as thromboprophylaxis for Chinese patients intended for thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the safety profile of preoperative administration of heparin for thromboprophylaxis in patients intended for thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery.

Methods

Patients

Our current study was conducted prospectively and approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (approval number: 20160601). Patients who were intended to receive thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery (including lobectomy, esophagectomy, and thymectomy) under general anesthesia in our hospital from June 2016 to August 2016 were recruited in our study. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before taking part in our study. All those patients were routinely screened for VTEs by ultrasound before hospital admission. The inclusion criteria were as follow: (I) 18–75 years old without any preoperative VTEs; (II) patients intended for video-assisted thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery (including lobectomy, esophagectomy, and thymectomy). The exclusion criteria included: (I) patients with coagulation disorders: preoperative international normalized ratio (INR) >1.5, or blood platelet count <50×109/L; (II) patients receiving any therapeutic anticoagulation preoperatively; (III) patients undergoing planned open thoracic surgery; (IV) patients with severe renal or liver dysfunction.

Procedure

This is a single center study conducted in the Department of Thoracic Surgery, West China Hospital, Sichuan University from May 2016 to August 2016. All those included patients were treated by one single surgical team (directed by Dr. Lin) and were randomly assigned into two groups by computer after admission into our department: the case group started heparin sodium (5,000 U, bid) rightly after admission and continued until discharge, and the control group started heparin sodium (5,000 U, bid) from the first postoperative day and also continued until discharge. If the postoperative drainage volume exceeded 500 mL per day, heparin sodium would be temporally ceased and re-started when the drainage volume was less than 500 mL per day in both group. The indications for remove of chest tube was the same in both groups: (I) for lobectomy and thymectomy, if the chest tube drainage volume was less than 250 mL/day, without air leak, the tube would be removed; (II) for esophagectomy, the chest tube would be removed if the drainage volume was less than 250 mL/day after oral intake begins (usually on postoperative day 6). All those patients were again routinely screened for VTEs rightly after remove of chest tube.

Data for analysis

The baseline data including demographic data as well as preoperative coagulation function data [blood platelet count, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), and INR] and major comorbidities of those included patients (including high blood pressure, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, mild to moderate narrow in coronary artery, and arrhythmia) were collected and compared. The end points included operation time and data for postoperative coagulation function as well as data of intraoperative bleeding volume and postoperative chest tube drainage (collected by other colleagues in our department who were outside of the trial).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0 software (SPSS Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). Data were represented as the mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables or number (%) for categorical data. For continuous variables, Student’s test was applied; while for categorical data, the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was applied. A two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

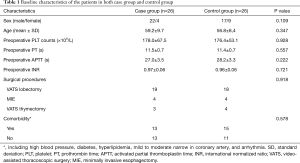

Baseline level characteristics of the included patients

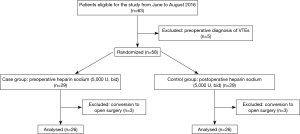

A flow chart of the recruitment of those patients was shown in Figure 1. A total of 58 patients who met the inclusion criteria were randomized into case and control groups upon the admission day by computer: 29 patients in case group and 29 patients in control group. All of those patients intended to undergo thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery (consisting of lobectomy, esophagectomy, and thymectomy). Six patients who were converted to open surgery were excluded from analysis because the intraoperative bleeding volume had been greatly influenced by their conditions of severe pleural adhesion or bleeding happened in dissecting the major vessels invaded by the tumor. The baseline characteristics of those included patients in both groups were comparable, and major comorbidities of the patients in each group were also similar (Table 1).

Full table

Safety profile of preoperative administration of heparin for patients undergoing thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery

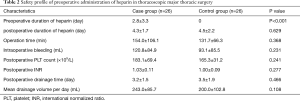

The intraoperative and postoperative characteristics for each group were listed in Table 2. Although the postoperative duration of the administration of heparin in each group was similar (P=0.629), the preoperative duration was significantly longer in the case group than that in control group (2.8±3.3 and 0 days, respectively; P<0.001). However, the operation time in each group was not significantly different (154.0 and 131.7 min, respectively; P=0.368). Even though the mean intraoperative bleeding tended to be increased in case group compared with control group (120.8 and 92.1 mL), no significant difference was observed (P=0.231). No significant difference was also observed in postoperative INR (1.03 and 1.00, respectively; P=0.227), postoperative platelet count (183.1×109/L and 165.3×109/L, respectively; P=0.241), and postoperative drainage time (3.2 and 3.5 days, respectively; P=0.466) between these two groups. Moreover, postoperative chest tube drainage volume also showed no significant difference between the two groups (243.0 and 200.0 mL/day, respectively; P=0.108).

Full table

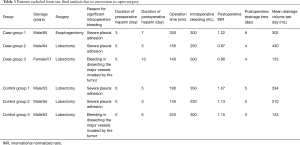

The detailed characteristics of those patients excluded from final analysis due to conversion to open surgery were also presented in Table 3. In these patients with open surgery, the intraoperative time and bleeding volume as well as postoperative chest tube drainage volume and duration seemed not to be different in those two groups. Moreover, the coagulation function of those patients undergoing open thoracic surgery was not significantly influenced in the case group as compared with control group.

Full table

All of our patients had no major postoperative complications such as severe pulmonary infection, bronchopleural fistula, or anastomosis leakage.

Efficacy of preoperative administration of heparin for thromboprophylaxis in thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery

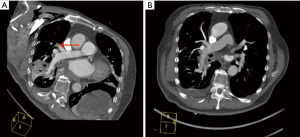

No VTEs was observed in control group, but there is one case of PE happened in the case group. This 61-year-old male patient was diagnosed with lung cancer and hyperlipidemia, and underwent lobectomy. On postoperative day 2, he suffered transient syncope, and the following computed tomography pulmonary angiography uncovered small embolisms in the pulmonary artery (Figure 2). This patient recovered quickly after continued administration of heparin plus warfarin.

Discussion

PE caused by DVT represents a disastrous complication for both surgical and nonsurgical patients. The risk factors associated with VTE included age, bed rest, malignancy, as well as surgical procedures, and so on (12). Therefore, patients undergoing major thoracic surgery especially for cancers were at a relatively high risk of VTE perioperatively (13). Current guidelines have recommended thromboprophylaxis for those high-risk patients (3). As to thoracic surgery, for the fear of increased bleeding during surgical procedures, the thromboprophylaxis often starts postoperatively or 6–12 h before operation. Obviously, this kind of thromboprophylaxis only aims to prevent surgery-induced VTE, lacking of the concerns for prevention of VTE caused by other conditions (for example, age, bed rest, and malignancy). Despite of the postoperative administration of thromboprophylaxis, there was still chance of VTE after thoracic surgery (7,8). Here comes the question: whether postoperative administration of heparin is sufficient for patients undergoing major thoracic surgery and whether prolonging the preoperative time of administration of heparin is reasonable and safe. Recently, American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines have recommended starting heparin as thromboprophylaxis of orthopedic surgery 12 hours or more preoperatively (11), and some studies have found that preoperative start LMWH yielded lower mortality rate as compared with postoperative start without any increased risk of bleeding complications in patients with orthopedic surgery (14). Therefore, we hypothesized that preoperative administration of heparin for thromboprophylaxis in major thoracic surgery is reasonable and safe. Herein, we conducted this pilot randomized controlled study to explore the safety profile of preoperative administration of heparin as thromboprophylaxis for patients intended for thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery. To our best knowledge, this is the first study of the current issue.

In our study, we randomized 58 patients who were intended for thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery into case group (the preoperative heparin group) and control group (the postoperative heparin group). The baseline characteristics of both groups were comparable. Preoperative administration of heparin did not significantly increase the operation time. Even though preoperative administration of heparin tended to increase the intraoperative bleeding, it did not show significant difference. Moreover, we believe that a mean intraoperative bleeding volume of 120.8 mL in the preoperative heparin group was rational and acceptable as compared with 92.1 mL in the postoperative heparin group. We also found that preoperative administration of heparin did not influence postoperative coagulation function or increase the chest tube drainage duration time. Moreover, preoperative administration of heparin did not significantly increase the mean drainage volume per day compared with postoperative administration of heparin. The similar results could also be observed in those excluded patients who experienced conversion due to severe pleural adhesion or tumor invasion. Therefore, our study proved that preoperative administration of heparin as thromboprophylaxis for patients intended for major thoracic surgery was safe without significantly increased risk of bleeding (a numeric difference of about 30 mL in intraoperative bleeding). Interestingly, in all of our patients, only one patient started preoperative administration of heparin was incidentally diagnosed with mild PE due to less prominent symptom of transient syncope and he recovered soon from continued administration of heparin plus warfarin. Considering the fact that this patient just started heparin only one day before operation, we suspect that if he could have started heparin earlier preoperatively he would probably avoid PE. On the other hand, the reason why he only had suffered minor symptom and recovered quickly could be well explained for the fact that he had preoperative administration of heparin.

Heparin exerts its anticoagulant function via catalyzing the inactivation of thrombin, factor Xa, and other clotting enzymes (15), and it is one of the commonly used anticoagulants in clinical practice as it was applied in our current randomized controlled study due to its cost advantages (16). However, heparin could also bind to cells and plasma proteins, which could lead to side effects of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and osteoporosis (15). Thus, LMWH, which has more predictable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties, has become more popular and replaced heparin in many clinical indications (15,17). Recent studies have compared the thromboprophylaxis efficacy of heparin with that of LMWH and found that LMWH was as effective as heparin for VTE prevention (18,19) and was even superior in PE prevention to heparin (20). However, due to longer activity duration of LMWH, there is a potential increased risk of bleeding. Therefore, the roles of heparin and LMWH playing in VTE prevention for major thoracic surgery still need to be well established.

Even though our pilot study proved that preoperative administration of heparin as thromboprophylaxis in Chinese patients intended for thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery was safe and reasonable, there are still several limitations. First, as a pilot study, a relatively small sample size could limit our analytical power. Second, due to low occurrence rate of VTE, the actual efficacy of preoperative administration of heparin needs to be validated. Finally, in our study, we only conducted this pilot study in Chinese patients, while for African and Caucasian patients, further studies are needed. Moreover, LMWH is also worthy of being studies.

Conclusions

In this pilot randomized controlled study, we explored the safety profile of preoperative administration of heparin as thromboprophylaxis in thoracoscopic major thoracic surgery in Chinese patients. Our study proved that preoperative administration of heparin was safe and reasonable in patients intended for major thoracic surgery. Our trial keeps going on, and we will present our further results in the future.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81672291, No. 31071210) (to YD Lin).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (approval number: 20160601) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

References

- Di Nisio M, van Es N, Büller HR. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Lancet 2016;388:3060-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Monreal M, Mahé I, Bura-Riviere A, et al. Pulmonary embolism: Epidemiology and registries. Presse Med 2015;44:e377-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141:e227S-77S.

- Avidan MS, Smith JR, Skrupky LP, et al. The occurrence of antibodies to heparin-platelet factor 4 in cardiac and thoracic surgical patients receiving desirudin or heparin for postoperative venous thrombosis prophylaxis. Thromb Res 2011;128:524-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Attaran S, Somov P, Awad WI. Randomised high- and low-dose heparin prophylaxis in patients undergoing thoracotomy for benign and malignant disease: effect on thrombo-elastography. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:1384-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song JQ, Xuan LZ, Wu W, et al. Low molecular weight heparin once versus twice for thromboprophylaxis following esophagectomy: a randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled trial. J Thorac Dis 2015;7:1158-64. [PubMed]

- Gómez-Hernández MT, Rodríguez-Pérez M, Novoa-Valentín N, et al. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in elective thoracic surgery. Arch Bronconeumol 2013;49:297-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhong M, Tan L, Xue Z, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation as a bridge therapy for massive pulmonary embolism after esophagectomy. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth 2014;28:1018-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blom JW, Doggen CJ, Osanto S, et al. Malignancies, prothrombotic mutations, and the risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA 2005;293:715-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Di Nisio M, Peinemann F, Porreca E, et al. Primary prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing cardiac or thoracic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015.CD009658. [PubMed]

- Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141:e278S-325S.

- Caprini JA. Thrombosis risk assessment as a guide to quality patient care. Dis Mon 2005;51:70-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agnelli G, Bolis G, Capussotti L, et al. A clinical outcome-based prospective study on venous thromboembolism after cancer surgery: the @RISTOS project. Ann Surg 2006;243:89-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leer-Salvesen S, Dybvik E, Dahl OE, et al. Postoperative start compared to preoperative start of low-molecular-weight heparin increases mortality in patients with femoral neck fractures. Acta Orthop 2017;88:48-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Garcia DA, Baglin TP, Weitz JI, et al. Parenteral anticoagulants: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012;141:e24S-43S.

- Olson EJ, Bandle J, Calvo RY, et al. Heparin versus enoxaparin for prevention of venous thromboembolism after trauma: A randomized noninferiority trial. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2015;79:961-8; discussion 968-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abi Ghanem M, Saliba E, Irani J, et al. Effects of preoperative enoxaparin on bleeding after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Med Liban 2015;63:185-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- PROTECT Investigators for the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, Cook D, Meade M, et al. Dalteparin versus unfractionated heparin in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1305-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pastores SM, DeSancho MT. ACP journal club. Dalteparin was at least as effective as UFH for VTE prevention in critically ill patients, with similar costs. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:JC13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li G, Cook DJ, Levine MA, et al. Competing Risk Analysis for Evaluation of Dalteparin Versus Unfractionated Heparin for Venous Thromboembolism in Medical-Surgical Critically Ill Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1479. [Crossref] [PubMed]