The great challenge of the public health system in Spain

Introduction

Article 43 of the Spanish Constitution of 1978 establishes the right to health protection and healthcare for all citizens (1). The political organization of the Spanish state is made up of the central state and 17 highly decentralized regions (termed autonomous communities) with their respective governments and parliaments. In terms of health care, political devolution to regional governments has been incrementally implemented over the last 35 years. The taking-up of responsibilities in the field of health by the autonomous communities brings the management of healthcare closer to citizens and guarantees (2):

- Equity: access to benefits and right to health protection under conditions of effective equality throughout the country and free movement of all citizens.

- Quality: in the evaluation of the benefit delivered by clinical actions, incorporating only those which contribute added value to the improvement of health, implicating the healthcare system.

- Participation: public of citizens both in respect for the autonomy of their individual decisions as well as in the consideration of their expectations as users of the healthcare system.

Spanish health system

Over the last years, the establishment of health systems providing universal coverage in the most advanced European countries has contributed to a permanent improvement in many health indicators like population health status parameters, health care amenable outcomes, coverage, access and financial equity parameters, health care quality, users’ satisfaction and system legitimated by the population. According to the last OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) health statistics report, Spanish life expectancy is the highest in Europe (2.7 years above average) (3), clinical results are at the level of the most advanced countries (same cancer survival rates as in Sweden, France or Germany) (4) and its cost is on the average of the 35 OECD economies, in terms of total spending on gross domestic product (GDP), 9%, and below the average if we compare it in terms of per capita spending (5,6). In addition, it is an international benchmark for its universality and level of access compared to many other developed countries.

This improvement in all these parameters has been associated to a continued increase in health spending. In all EU countries (including Spain), during most of the second half of the 20th century, health expenditure has been growing faster than national income. The same is happening in all member countries of the OECD, so this situation calls into question whether the economic sustainability of healthcare systems, most of which were created and developed in times of greater prosperity, will be guaranteed in the future (7). In the context of a worldwide economic crisis, the impact of financial difficulties of healthcare systems has become particularly evident in Spain, where unemployment rate is one of the highest in the European Union.

Governance of the health system and management autonomy

The world health organization (WHO) defines governance for health as the attempts of governments or other actors to steer communities, countries or groups of countries in the pursuit of health as integral to well-being through both whole-of-government and whole-of-society approaches (8). In Spain, as previously commented, health system governance is decentralized. During the last decade, though the decentralization paradigm has not been put into question, there have been measures aimed at “striking a balance” between decentralization and the national character of the health systems. In response to the economic crisis, the role of the national level has been strengthened.

The autonomy of health institutions is imperative to obtain greater and better use of resources. We truly believe that management autonomy involves the transfer of responsibility to hospitals and their professional staff. In order to obtain this autonomy, the institutions need to have legal standing and a professional governing body that is independent and not politically colonized. In addition, some variables have been cited as essential requirements for good government: transparency, accountability and incentives to promote participation (9). Unfortunately, none of these characteristics are found in the Spanish health care system.

Health care spending

The containment of health care expenditure is one of the major challenges facing public policymakers in the developed countries. Expenditure on health care is driven by a complex set of interrelated demand and supply side factors. In Spain, several factors have clearly contributed to the continued growth of health spending.

Demand and use of services

In the last years, it has been a progressive demand and use of health services due to the aging of the population, the chronification of diseases and the increasing medicalization of the population. The aging of the population is considered one of the most important factors in all developed countries and, as suggested by some authors, may be responsible for around 20% of the increase in health spending. In spite of this widespread belief that links the average health care expenditure to the age of an individual, several studies show that the demand for and use of health care depends ultimately on the health status and functional ability of citizens (10). The population of Spain is highly aged and we know that almost 80% of the consumption of health resources occurs in individuals above 65 years old. Also of remark, Spain is one of the European countries where individuals visit the doctor more often: there are 7.5 visits per capita per year, whereas in Sweden the rate is 2.9 visits per year (6). Another factors that have also contributed to raised health care spending are unhealthy lifestyles, particularly obesity. Spain is one of the European countries with a higher percentage of obese individuals.

Technology and medical progress

On the supply side, technological developments and constant evolution in the state of the art of medical science are variables that have decisively contributed to improving public health but also major factors affecting the level and rate of change in health care spending. Medical technology can be defined as the drugs (pharmaceuticals and vaccines), medical equipment, health-care procedures, supportive systems, and the administrative systems that can tie all these disparate elements together (10).

Pharmaceutical expenditures

In the recent published OECD health statistics report (11), the current expenditure on pharmaceuticals (prescribed and over-the-counter medicines) and other medical non-durables in Spain reached the 17,9% of current expenditure on health (1,6% above the OECD countries average, year 2014). In terms of impact on GDP (year 2013), pharmaceutical spending represented 1.6% of GDP, ranging from 0.5% in Denmark to 2.8% in Greece (year 2013, 1,4% average, OECD countries).

In most OECD countries, pharmaceutical expenditure containment policies have been introduced in the last years, generally based on price controls, the number of prescriptions, the introduction of generic medicines and increasing costs assumed by users. In Spain, it has been a reduction in pharmaceutical expenditure, which fell by more 6% in real terms in 2011. Spain has introduced a series of measures to reduce spending on pharmaceuticals, including a general rebate applicable for all medicines prescribed by national health service physicians in 2010, and mandated price reductions for generics and increase in co-payments in 2012. The share of the generic market also doubled in Spain between 2008 and 2012, to reach 18% of the total pharmaceutical market in value (40% in volume) (12).

Finally, a new debate is ongoing regarding the impact of new high cost, specialty medicines targeting small populations on the long term sustainability and efficiency of pharmaceutical spending.

Efficiency of the model

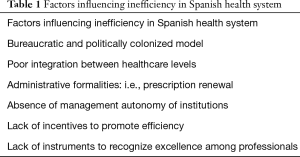

Improving health care system management efficiency may be an alternative to be considered in containing health care expenditure. The application of efficiency concepts to health care systems is challenging. Measurement of productive efficiency is based on the relationship between output produced and inputs required for production. This measurement is not free from difficulties. In the particular case of health care efficiency, despite even the definition of output is not exempt from controversies, the literature appears to have reached a consensus on life expectancy as the main output in the health care production function (13). OECD [2010] estimates that average life expectancy could increase by about 2 years for the OECD as a whole, if resources were used more efficiently. Although the results depend on the indices taken in account, there are significant differences across countries in health care management efficiency levels. In an analysis of efficiency estimates of different health care systems, Spain consistently scores among the top seven performers in most of the models and is clustered in the group of countries with highest average efficiency scores (14). The prevailing model in Spain is salaried professionals and despite the difficulties in applying efficiency concepts to health systems, there is a considerable body of evidence on the pervasiveness of inefficiency in the health sector (15). Several factors have been related to the lack of efficiency, directly influencing the overall growth of health spending (Table 1).

Full table

Conclusions

In terms of socio-economic development and in relation to similar countries, the Spanish health system is generally comparable in almost all dimensions: population coverage, global equity, access equity, technical quality and economic efficiency.

The Spanish national health system is in itself a great success of Spanish society, for its technological capacity and human capital, for the accessibility of its service network, for offering access to the latest advances in medicine and medical technology. For the entire Spanish population, the national health service represents security and tranquility in case of illness or accident. All these characteristics have a great consensus and social support, only clouded by the surprisingly low priority that health—and to a lesser extent other public services—have on the Spanish political agenda. The sustainability of the system is under debate. There are basically three ways to guarantee the financing of a quality public health system with universal coverage and free of charge: to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the health provision system, prioritize health spending in relation to other public policies and/or increase income taxes for that purpose.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Constitución Española. Boletín oficial del Estado. Gaceta de Madrid. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-1978-31229

- Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality. National Health System of Spain, 2012 [Internet monograph]. Madrid; 2012. Available online: www.msssi.gob.es

- OECD Health Statistics 2016 - Frequently Requested Data. October 2016. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/oecd-health-statistics-2014-frequently-requested-data.htm

- Sant M, Allemani C, Santaquilani M, et al. EUROCARE Working Group. EUROCARE-4. Survival of cancer patients diagnosed in 1995-1999. Results and commentary. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:931-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- OECD Health Statistics 2016 - Frequently Requested Data. October 2016. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/oecd-health-statistics-2014-frequently-requested-data.htm

- OECD, Health Policy Studies. Value for Money in Health Spending. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2010.

- Peiró M, Barrubés J. New context and old challenges in the healthcare system. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2012;65:651-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kickbusch I, Gleicher D. Governance for health in the 21st century. World Health Organization 2012.

- Meneu R, Ortún V. Transparencia y buen gobierno en sanidad. También para salir de la crisis. Gac Sanit 2011;25:333-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Przywara P. Projecting future health care expenditure at European level: drivers, methodology and main results. European Commission 2010.

- OECD Health Statistics 2016 - Frequently Requested Data. October 2016. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/oecd-health-statistics-2014-frequently-requested-data.htm

- OECD (2015), Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/ [Crossref]

- Hernández de Cos P, Moral-Benito E. Health care expenditure in the OECD countries: efficiency and regulation. Documentos Ocasionales 2011.

- Medeiros J, Schwierz C. Efficiency estimates of health care systems in the EU. European Commission. Economic papers 2015;549.

- Beltrán A, Forn R, Garicano L, Martínez M, Vázquez P. Impulsar un cambio posible en el sistema sanitario. Madrid: McKinsey & Company y FEDEA; 2009 y García Vargas J, Pastor A, Sevilla J. Diez temas candentes de la sanidad española para 2011. El momento de hacer más con menos. Madrid: Pricewaterhouse-Coopers, S.L.; 2010.