Comparison of multiple techniques for endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration specimen preparation in a single institution experience

Introduction

Endobronchial ultrasound-transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) is a well established, minimally invasive procedure for biopsy of mediastinal structures under real-time ultrasound guidance. Introduced in the last decade, this technique has been the subject of many publications that have analyzed performance influencing factors, such as needle size, number of passes per lymph node, use of suction and rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) of sampling (1,2). Multiple techniques for specimen acquisition and preparation have been described, but only few studies comparing these techniques have been published (3,4). Currently there is no consensus on the optimal EBUS-TBNA specimen preparation method.

Here we aimed to analyze and compare five methods of EBUS-TBNA specimen preparation (cytology slides, cell-block, core-tissue, combination of cytology slides and core-tissue, combination of cytology slides and cell-block) in order to identify the technique(s) with the highest diagnostic performance.

Methods

We retrospectively collected and analyzed the data of the consecutive series of patients who underwent EBUS-TBNA between January 2012 and December 2014 at the Center for Thoracic Surgery of the University of Insubria, Ospedale di Circolo, Varese, Italy. Ethical approval was not required, as this study was observational. De-identified data were used for analyzing the results. Individual patient consent was waived due to the study retrospective nature.

For each patient we collected the following data: age, gender, suspect diagnosis, station and size of sampled lymph nodes, size of needle used during the procedure and number of passes performed for each lymph node station, procedure duration, specimen preparation technique, pathologic diagnosis and patient follow-up.

All EBUS-TBNAs were performed by two experienced bronchoscopists on rotation, under monitored conscious sedation with midazolam, fentanyl and topical anesthesia (lidocaine). The instrument used was an ultrasonographic bronchofibervideoscope, 6.9 mm wide, with 2.2 mm working channel, 35° optical system and EU-C60 7.5 MHz ultrasound processor (BF-UC180F, Olympus Medical System). Each lymph node station was sampled 1 to 3 times using 22- or 21-G needle (NA-201SX-4022/21, Olympus Medical System). ROSE was not used. The specimen was processed using 1 of 5 different techniques: cytology slides, cell-block, core-tissue, combination of cytology slides and core-tissue, combination of cytology slides and cell-block.

The cytology slides were prepared by smearing the specimen on two glass slides, one of them with 95% ethanol fixation. The cell-block was obtained by extruding material directly from the needle lumen into polyethylene glycol solution. The core-tissue was collected with 21-G needle and ejected directly into formalin solution. The samples were read by two pathologists dedicated to thoracic diseases, and disagreement was resolved by consensus.

EBUS-TBNA cytohistological results were classified inadequate in presence of an excess of red blood cells, or if only bronchial cells were identified, or if the concentration of lymphocytes was not representative of lymph node tissue. Pathological and non-pathological adequate results confirmed at surgery or at 1-year follow-up were defined respectively true positive and true negative. EBUS-TBNA pathological results confirmed to be non-pathological at surgery or at 1-year follow-up were defined false positive. Finally, non-pathological adequate results confirmed to be pathological at surgery or at 1-year follow-up were defined false negative.

Diagnostic yield (percent of adequate samplings), diagnostic accuracy and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were calculated for each of the five specimen preparation techniques and compared.

Continuous data were reported as median with interquartile range (IQR). Categorical and count data were presented as frequencies and percentages. The diagnostic yield and diagnostic accuracy of the five specimen processing techniques were compared using the Chi-square test. The AUCs were compared by the DeLong method. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were undertaken using MedCalc statistical software version 17.1 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium; http://www.medcalc.org; 2014).

Results

In the period 2012–2014 overall 199 patients underwent EBUS-TBNA. Of these patients, 145 (73%) were male, and median age was 64 years (IQR: 52–74 years). The 139/199 cases (70%) were clinically suspect for neoplastic disease and 60 (30%) for granulomatous disease. Three lymph node stations were sampled in 5 patients (3%), two stations in 56 patients (28%), only one node station in 138 patients (69%). The 21-G needle was used in 83% of cases, the 22-G in 17%. The median number of passes performed for each lymph node was 3 (IQR: 2–4). The median duration of the procedure was 20 min (IQR: 20–30 min). No severe complications occurred. Only in one case a cardiac patient developed an atrial fibrillation after the procedure. The sampled lymph node stations were: right or left high-paratracheal in 3% (5/199) of cases, right or left inferior-paratracheal in 43% (86/199), subcarinal in 65% (130/199). The sampled lymph node median size was 22 mm (IQR: 19–32 mm).

The specimen-processing techniques used were: cytology slides in 42 cases (21%); cell-block in 25 (13%); core-tissue in 60 (30%); combination of cytology slides and core-tissue in 51 (26%); combination of cytology slides and cell-block in 21 (10%).

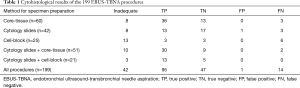

The results are summarized in Table 1. EBUS-TBNA sampling was inadequate in 42/199 cases (21%). Among the 157 adequate samples, 95 were true positive (72 malignant and 23 granulomatous diseases); 1 case (0.6%) was false positive (EBUS-TBNA cytology slides interpreted as lymphoma, but further biopsies—a second EBUS-TBNA and a subsequent surgical biopsy—revealed a normal lymph node, in presence of lung interstitial disease); there were 14 false negative results (9%).

Full table

Sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV) and diagnostic accuracy among all EBUS-TBNA procedures were respectively 87%, 98%, 77% and 90%. The false negative rate expressed as the ratio of false negative EBUS-TBNAs/all adequate EBUS-TBNA samplings, was 9% (14/157).

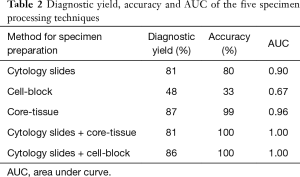

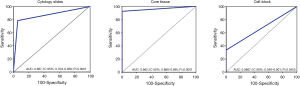

Diagnostic yield, accuracy and AUC are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. EBUS-TBNA specimen preparation with cytology slides and core-tissue had high and similar diagnostic performance; the two methods did not show significantly different diagnostic yield (81% vs. 87%; P=0.44) and AUC (0.90 vs. 0.96; P=0.15).

Full table

Discussion

EBUS-TBNA with its high sensitivity and specificity is an effective tool for diagnosis of hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes suspect of malignant or granulomatous disease involvement. However, the risk of false negative EBUS-TBNA biopsies is a relevant issue, as the pooled NPV was 89% (range, 57–93%) in the recently reviewed literature (5). The 77% NPV recorded in our study likely reflects the scarce performance of the cell-block method in our hands, and the learning curve of the three different methods tested for the preparation of samples. If we exclude the 25 cases processed only by the cell-block method, in our series the NPV was 85%, in agreement with the literature (5). The suboptimal NPV generally recorded suggests that when the clinical-radiological suspicion of mediastinal node involvement is high and the EBUS-TBNA biopsy is negative, repeat nodal biopsy (by EBUS-TBNA or mediastinoscopy) should be done. Regarding EBUS-TBNA specimen preparation method, cytology slides and core-tissue technique in our study demonstrated a high and similar diagnostic performance, while the cell-block technique alone showed a poor yield. Notably, in our experience the highest diagnostic yield of EBUS-TBNA was attained by the combination of two methods (cytology slides and core-tissue, or cytology slides and cell-block).

The diagnostic yield of slide cytology and core-tissue are reported to be greater than 80% also in previous series (4,6-8). In our study no significant differences were seen between the diagnostic performances comparing these two techniques. Comparing cytology slides and core tissue samplings, in cases of benign disease Toth et al. identified a significantly higher diagnostic performance of core-tissue biopsy (4). However, these authors suggested to use both slide cytology and core-tissue sampling, since their combination provided fewer missed diagnoses than either individually (4).

Regarding cell-block, our results are not as satisfactory as the >80% diagnostic accuracy reported in the literature (3,7,9,10). This discordance could be due in part to our pathologists’ scarce confidence with cell-block technique, as cytology slide and core-tissue are the predominantly used methods in our institution. Therefore our results with the cell-block technique should be considered with caution.

The use of two combined sampling techniques led to ideal diagnostic performance results in our study. Also in the literature the combination of two techniques, both slide cytology and cell-block or core tissue, are reported to increase the diagnostic performance of the same methods alone (4,6-8). However, processing the specimen in two different ways at the same time requires more resources and raises the question of which method should be trusted in case of discordant results.

Our results suggest to adopt either slide cytology or core-tissue as EBUS-TBNA specimen processing technique, since the combination of two methods is more resource-consuming. However, considering the impact of the pathologists’ expertise on the diagnosis of the processed sample, we concur with Heijden et al. that the EBUS-TBNA specimen processing method should be chosen according to the preference and expertise of the pathology colleagues (3).

This study has limitations, as it is retrospective. However, all patient clinical records and EBUS-TBNA results were reviewed, thus providing more granular data than an administrative study. Moreover, in the vast majority of patients (97%) of our series only one or two node stations were sampled. Nonetheless in our hands the diagnostic performances of the specimen processing techniques analyzed are similar to those reported in the literature, except for the cell-block, suggesting that they are well representative of the overall scenario. A point of strength is that all EBUS-TBNA procedures were performed by the same team of two expert bronchoscopists on rotation, and the cytohistological analyses were conducted by pathologists dedicated to thoracic diseases, reducing in this way the learning curve bias.

Conclusions

EBUS-TBNA is an accurate and safe technique, representing a precious tool for diagnosis of hilar and mediastinal lymph node disease involvement. In our single-institution experience, cytology slides and core-tissue preparations demonstrated high and similar diagnostic performance. Cytology slides in combination with core-tissue or cell-block showed the highest performance, however the simultaneous use of two methods is more resource-consuming. Finally, considering how much the pathologists’ confidence in using a familiar processing technique impacts on the final results, the specimen processing methods should be chosen according to the pathologist’s preference and expertise.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: Ethical approval was not required, as this study was observational. De-identified data were used for analyzing the results. Individual patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

References

- Wahidi MM, Herth F, Yasufuku K, et al. Technical Aspects of Endobronchial Ultrasound-Guided Transbronchial Needle Aspiration: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2016;149:816-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kennedy MP, Jimenez CA, Morice RC, et al. Factors influencing the diagnostic yield of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2010;17:202-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden EH, Casal RF, Trisolini R, et al. Guideline for the acquisition and preparation of conventional and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration specimens for the diagnosis and molecular testing of patients with known or suspected lung cancer. Respiration 2014;88:500-17. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toth JW, Zubelevitskiy K, Strow JA, et al. Specimen processing techniques for endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Ann Thorac Surg 2013;95:976-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dhooria S, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, et al. Utility and Safety of Endoscopic Ultrasound With Bronchoscope-Guided Fine-Needle Aspiration in Mediastinal Lymph Node Sampling: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Respir Care 2015;60:1040-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Santos J, Serra P, Andreo F, et al. Contribution of cell blocks obtained through endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration to the diagnosis of lung cancer. BMC Cancer 2012;12:34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alici IO, Demirci NY, Yılmaz A, et al. The combination of cytological smears and cell blocks on endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspirates allows a higher diagnostic yield. Virchows Arch 2013;462:323-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gauchotte G, Vignaud JM, Ménard O, et al. A combination of smears and cell block preparations provides high diagnostic accuracy for endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Virchows Arch 2012;461:505-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Navani N, Brown JM, Nankivell M, et al. Suitability of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration specimens for subtyping and genotyping of non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter study of 774 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:1316-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steinfort DP, Russell PA, Tsui A, et al. Interobserver agreement in determining non-small cell lung cancer subtype in specimens acquired by EBUS-TBNA. Eur Respir J 2012;40:699-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]