Outcomes after implementing the enhanced recovery after surgery protocol for patients undergoing tuberculous empyema operations

Introduction

In addition to conservative drug therapy, surgical management has become a mandatory treatment option for patients with tuberculous empyema. Surgical management exhibits several advantages including facilitating diagnosis of the disease condition and stage, alleviating infection, re-expanding the compressed lung, and preventing subsequent chronic respiratory lesion. Several surgical modalities are options for primary empyema management, including surgical drainage, lavage techniques, debridement by video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), decortication, thoracoplasty, and open window thoracostomy (1). With the wide application of decortication by VATS, it is imperative to develop a suitable auxiliary scheme to improve postoperative recovery and quality of life.

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols are currently applied for the care for subjects undergoing lung resection surgery (2). High-rank evidence retains to sustain their applications (3). ERAS involves preoperative optimization, minimization of preoperative fasting, and normal physiological restoration. However, there is relatively scarce data on the application of ERAS protocols in patients undergoing tuberculous empyema operations. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to identify differences in these specific outcomes. In addition, no investigations have yet evaluated the effect of ERAS protocols on quality of life outcomes (4). Moreover, a previous report noted heterogeneity in the characterizations of ERAS programs (5).

Real-time clinical practice usually incorporates advancements over time as new evidence becomes available. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the recommendations of an ERAS program for tuberculous empyema patients undergoing VATS. The study was conducted over a 5-year period to determine whether the introduction of ERAS protocols shortens the length of hospital stay for patients and improves their quality of life.

Methods

Subject enrollment

All subjects were diagnosed with tuberculous empyema based on the following criteria: patients exhibited fever, emaciation, fatigue, chest pain, cough, and shortness of breath with a history of tuberculosis pleurisy. Local chest percussion demonstrated dullness or flatness, and auscultation indicated that breath sounds were absent or diminished. Thoracentesis obtained straw yellow colored turbid liquid or pus. X-ray or computed tomography demonstrated pleural wall thickening and pleural effusion, together with oppressive pulmonary atrophy.

All of the subjects received at least 2 weeks of standard antituberculosis therapy before surgery to control tuberculosis and prevent dissemination and recurrence. The therapy consisted of 0.3 g isoniazid once a day, 0.45 g rifampicin once a day, 0.75 g ethambutol once a day, and 0.5 g pyrazinamide 3 times a day. The inclusion criteria included age ≥14 and ≤70 years old; no severe organic disease in the brain, heart, liver, and kidney; no pulmonary cavity, bronchiectasis, or bronchial stenosis; no bronchopleural fistula or pyothorax penetrating the chest wall; pleural thickening <1.0 cm without calcification; and no obvious thoracic collapse or intercostal stenosis. The exclusion criteria were age <14 or >70 years old, high surgical risk due to severe organic disease, ineffective antituberculosis therapy, and significant foci absorption after antituberculosis therapy. The subjects were randomly divided into the ERAS group and the conventional control group.

ERAS procedure

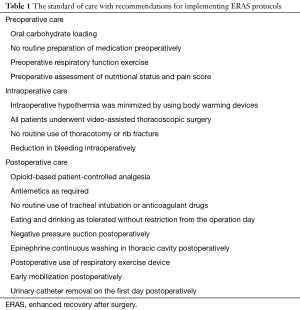

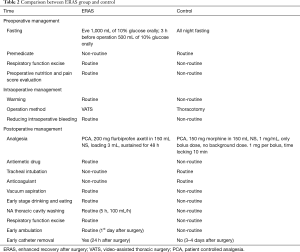

All patients were treated by VATS lesion clearance plus fibrous dissection. The ERAS principles for preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care are listed in Tables 1 and 2 (6). Each patient met with the nurses and physicians in the outpatient clinic before surgery. At this time, the patients were informed of their prospective date of discharge. After surgery, patient-controlled non-opioid analgesia was employed until the patient seemed comfortable with regard to oral analgesia.

Full table

Full table

Patients were considered ready for discharge when their indexes were regular and their pain was suitably managed by oral analgesics. The patients also needed to have an adequate diet and social support. Increased levels of C-reactive protein and prothrombin and decreased hemoglobin were not considered contraindications for discharge; however, these tendencies and evidence of stability were believed to be important. Each patient was reexamined on the 7th day after discharge.

Data collection

The intraoperative information included the size of the incision, continuous rinsing with adrenaline saline, regional blockade with intercostal nerve block or intravenous morphine, and persistent negative pressure aspiration (7,8). The postoperative data included the time of chest tube placement, volume of pleural fluid drainage, and the incidence of complications.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed on SPSS 22.0 software. The measurement data were depicted as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were compared by the t-test. The enumeration data were compared by the chi-square test. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

General information

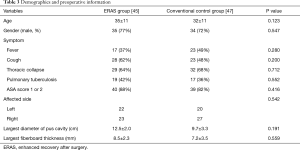

A total of 94 patients who underwent tuberculous empyema operations performed by a single surgical team at the Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital between March 2011 and March 2016 were evaluated in this retrospective analysis. Two patients were excluded from further analysis because of coagulation hemothorax clearance plus fibrous dissection (n=1) and pleural biopsy rather than lesion clearance plus fibrous dissection (n=1). The 92 patients had a total of 93 hospital admissions for tuberculous empyema procedures. One patient (1.08%) underwent two tuberculous empyema operations. The patient demographics and baseline characteristics, including age, gender, symptoms, ASA score, position, pus cavity diameter, and fiberboard thickness were collected and listed in Table 3. No statistical differences were observed in the preoperative information between the two groups.

Full table

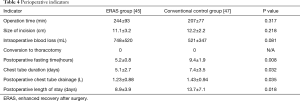

Perioperative comparison

Perioperative results are shown in Table 4. There were no statistical differences in the operation time, size of incision, and intraoperative blood loss between the two groups. No patients suffered from open surgery conversion in either group. Compared with the conventional control group, the patients in the ERAS group exhibited a significantly shorter postoperative fasting time, chest tube duration, and length of stay in the hospital (P<0.05). In addition, the volume of chest tube drainage in the ERAS group was smaller than in the conventional control group (P<0.05).

Full table

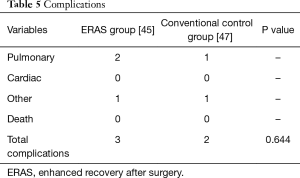

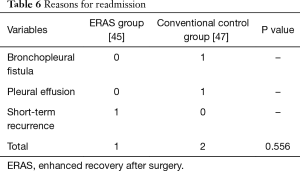

Comparison of complications

In total, 5 of the 92 patients (5.4%) had complications, including perioperative pulmonary atelectasis (n=2, 2.16%), bronchopleural fistula (n=1, 1.08%), postoperative active bleeding (n=1, 1.08%), and wound infection (n=1, 1.08%) (Table 5). No patient died postoperatively. The reasons for readmission included bronchopleural fistula (n=1, 1.08%), pleural effusion (n=1, 1.08%), and nearby recurrence (n=1, 1.08%) (Table 6). No significant differences were found in the complication and readmission rates between the ERAS group and conventional control group (P>0.05).

Full table

Full table

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that implementation of ERAS protocols for patients receiving tuberculous empyema operations led to a significant decrease in the median postoperative length of hospital stay from 13.7 to 8.9 days. This reduction is in agreement with a previous study of outcomes of tuberculous empyema operations (9). However, there is still lack of information about the role of ERAS protocols in patients undergoing tuberculous empyema operations. Therefore, it may be necessary to optimize the nontechnical aspects of the ERAS protocols rather than focusing attention on the minimally invasive procedures. A previous study (10) reported that this optimization is important given the similarity in economic cost between minimally invasive surgery and open surgery. Thoracic surgeons performing VATS to treat tuberculous empyema require a relatively high level of technique, and the procedure has a long-term learning curve. Moreover, it should be noted that the present research did not evaluate other important aspects, such as the time required to resume work or ordinary activities following surgery. In terms of these aspects, VATS may demonstrate beneficial results compared with conventional open thoracotomy.

In two studies of patients (9,11) who underwent conventional hepatic resection, the mean lengths of stay were 6 and 7 days. A study on the application of the ERAS protocol for hepatic resection seemed to reduce the length of stay to shorter than 4 days. However, this improvement led to a higher readmission rate, which increased to 22% (6). This result emphasizes the need for early postoperative and follow-up care for patients when applying the ERAS protocol. Success of the ERAS protocol requires that surgeons pay close attention to patients to treat potential complications after tuberculous empyema operations and to minimize readmissions.

In this study, the incidence of postoperative complications was steady throughout the evaluation period. A previous study (12) demonstrated both a decreased complication rate and an increased readmission rate related to ERAS protocols. However, additional research is needed to determine the optimal postoperative length of stay and chest tube duration that minimizes the readmission rate. There are notable differences between the present study and the former report with regard to discharge exercises. For instance, Lin et al. (13) reported that a postoperative length of stay of 6 days was ideal, and considered discharge before this time to be too early. It is difficult to confirm in a retrospective study if discharge was premature; however, it should be noted that the same discharge criteria were maintained throughout this study.

There are several limitations in this study. One limitation is that it was a retrospective study, so it was inconvenient to collect all data on readmissions and complications because the patients could visit other hospitals and this information may have been lost. Additionally, this study could not fully evaluate factors affecting quality of life, which should be examined in future research.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Al-Kattan KM. Management of tuberculous empyema. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;17:251-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ansari BM, Hogan MP, Collier TJ, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial of High-Flow Nasal Oxygen (Optiflow) as Part of an Enhanced Recovery Program After Lung Resection Surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:459-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Evidence-based surgical care and the evolution of fast-track surgery. Ann Surg 2008;248:189-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loop T. Fast track in thoracic surgery and anaesthesia: update of concepts. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2016;29:20-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eskicioglu C, Forbes SS, Aarts MA, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs for patients having colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:2321-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Connor S, Cross A, Sakowska M, et al. Effects of introducing an enhanced recovery after surgery programme for patients undergoing open hepatic resection. HPB (Oxford) 2013;15:294-301. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deng B, Tan QY, Zhao YP, et al. Suction or non-suction to the underwater seal drains following pulmonary operation: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;38:210-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanni A, Critchley A, Dunning J. Should chest drains be put on suction or not following pulmonary lobectomy? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2006;5:275-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen B, Zhang J, Ye Z, et al. Outcomes of Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgical Decortication in 274 Patients with Tuberculous Empyema. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;21:223-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zehr KJ, Dawson PB, Yang SC, et al. Standardized clinical care pathways for major thoracic cases reduce hospital costs. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:914-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Molnar TF. Current surgical treatment of thoracic empyema in adults. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:422-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schatz C. Enhanced Recovery in a Minimally Invasive Thoracic Surgery Program. AORN J 2015;102:482-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin DX, Li X, Ye QW, et al. Implementation of a fast-track clinical pathway decreases postoperative length of stay and hospital charges for liver resection. Cell Biochem Biophys 2011;61:413-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]