小细胞肺癌的化疗进展

引言

肺癌是近几十年来世界范围内最常见的肿瘤,估计每年有160万新发病患者(占恶性肿瘤的12.7%)[1]。它也是恶性肿瘤导致死亡的首要原因,每年估计有138万人死于肺癌。SCLC占肺癌总数的10%~15%,其发病与长期吸烟有关[2]。因此,典型的SCLC患者一般是老年人、有吸烟史者或者重度吸烟者,并伴有多个心血管和肺部并发症,这可能会影响最佳治疗方案的效果。SCLC的特点是侵袭性、快速增长、癌旁内分泌性和早期转移。在发达国家,小细胞肺癌的发病率在1980年达到高峰,这于20年前的吸烟率高峰期相对应,目前由于吸烟模式的改变,发病率在缓慢下降[2,3]。

未经治疗的SCLC患者在2~4个月内就可出现死亡[3,4]。SCLC开始的治疗方案包括手术治疗,不能手术治疗的患者可以选择单独放疗[3,5]。最终证实,这两种治疗方案的长期生存率都非常低,且易出现早期复发,通常还伴有远处转移。1969年,有学者报道与支持疗法相比,单纯使用环磷酰胺化疗药物治疗,可以将存活率提高两倍[6]。随后,联合化疗被证实优于单一用药[7,8]。随着20世纪80年代的到来,联合化疗由于具有包括完全缓解的显著反应率,为肿瘤的治疗提供了新的希望。然而,SCLC在开始治疗时对化疗和放疗敏感,随后会出现不可逆的复发,对一线药物耐药或者治疗无效[9,10]。

对于其他一些恶性实体瘤,诊断和治疗方面的研究进展能够提高生存率。然而,对于SCLC来说,自过去的40年以来,其五年存活率却没有显著提高,目前仍趋于稳定状态[2,11,12]。在澳大利亚,1982—1987和2000—2007期间,男性的五年存活率提高了3%~5%,而女性提高了5%~8%[12]。

在过去的30年里,SCLCⅢ期临床试验仅平均提高了2个月的存活时间[10]。采取预防性脑照射的放射治疗方法,可以提高初始治疗达到完全或接近完全缓解的患者的存活率(3年生存率从5.4%提高至15.3%到20.7%)[13]。

与非小细胞肺癌相比,SCLC在肿瘤基因组学、化疗以及靶向治疗的进展相对缓慢。除了在20世纪70年代和80年代首次用于SCLC的化疗药物外,目前铂类与依托泊苷仍然是化疗的主要药物[14,15]。最近,对分子途径和基因异常可能参与SCLC发病机制的研究进展,有望为改善SCLC治疗效果提供新的治疗靶点[16,17]。

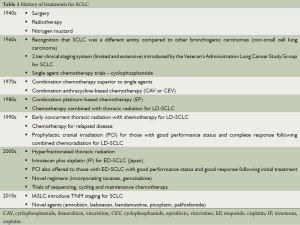

本文聚焦于化疗,简单介绍SCLC的治疗发展历史(表1)。然后,全面地介绍初发和复发疾病如何选择化疗方案,以及新出现的化疗药物和化疗方案。

Full table

SCLC:组织学和分期

SCLC最初被认为是由矿工接触砷而发病,并被冠以“纵隔腔的淋巴肉瘤”之名[18]。1926年,Barnard发现“燕麦细胞肉瘤”实际上来源于肺上皮细胞[19]。1967年,世界卫生组织(WHO)根据Barnard的观察将SCLC分为四种组织亚型。Barnard的观察包括:① 淋巴细胞样,② 多边形,③ 纺锤形,④ 其他[3,9]。随后,WHO又经过数次修订,直到1988年,国际肺癌研究协会(IASLC)使用“小细胞肉瘤”来代替“燕麦细胞肉瘤”。

1968年退伍军人局肺癌研究组引入SCLC的最初分期系统,包括局限期小细胞肺癌(LD-SCLC)和广泛期小细胞肺癌(ED-SCLC)两种临床亚型[20]。LD-SCLC定义为肿瘤部位和结节限制于半侧胸部,并可以被包括在一个放射治疗野内,除此之外的其他SCLC都是ED-SCLC[11,20]。

大概有30~40%的患者表现为LD-SCLC,最佳治疗方案是联合化疗和胸部放疗。中位存活时间为15~20个月,2年和5年存活率分别为20%~40%和10%~20%[21]。不幸的是,大部分(60%~70%)患者表现为ED-SCLC,通过联合化疗后中位存活时间为8~13个月。而且,2年和5年存活率都很低,分别为5%和1%~2%[21]。

很多文献都使用两个亚组的临床分期系统,它仍然与临床治疗决策相关。然而,在限制性患者组内,生存结果也有显著差异。当LD-SCLC根据IASLC的肿瘤大小、是否有淋巴结浸润和远处转移(TNM)(第7版,2010年)进一步分期,其5年存活率也从ⅠA期的38%降到ⅢB期的9%[11]。这也凸显出需要更精确分期的重要性,因此至少在非转移肿瘤临床试验阶段TNM分期是值得推荐的分期系统[11,15]。

联合化疗的进展

现在联合化疗作为整体方案被广泛接受,应用于各阶段的小细胞肺癌,这与以前的系统性治疗策略有一定差别[15,22,23]。20世纪40年代,手术方案开始用于治疗SCLC,直到1969年,放疗的治疗效果被证实优于手术治疗,甚至在可以手术的患者中也是如此[5,14,18]。早在1942年就开始使用烷基化制剂如氮芥,但是在当时SCLC的本质还没有被发现,所有的肺癌治疗方法都相似[18,23-26]。氮芥将肺癌的中位存活时间从93天提高到121天(特别注意的是468例患者中仅81例为燕麦细胞癌)[25,26]。1962年,Watson和Berg提出,燕麦细胞癌具有显著的进展性和早期转移的倾向,积极的化疗与放疗联合治疗比局部治疗(例如单独手术治疗或者放疗)更优越[23]。

与安慰剂相比,环磷酰胺作为一种细胞毒性化疗药物,是第一个被证实可以提高肺癌(包括SCLC)生存时间的药物[1969](4.0个月对比1.5个月)[6]。此外,1979年以环磷酰胺作为基础的化疗方案并联合胸部放疗,比单独放疗具有更好的治疗效果[7,27]。

紧随着环磷酰胺的可喜成果,关于肿瘤对单一细胞毒性制剂的总体有效率(ORR)出现了很多研究,这其中包括蒽环类抗生素、依托泊苷、阿糖胞苷、异磷酰胺、六甲密胺、顺铂、卡铂、长春地辛、长春新碱和尼莫司汀[28]。自此,鬼臼素(依托泊苷和阿糖胞苷)被认为是治疗SCLC最具有活性的单一药物[29-33]。事实上,使用三种不同给药时间表的依托泊苷的随机试验显示有效率为20%~62%[33]。烷化剂包括异磷酰胺显示总体有效率为46%[28],其他烷化剂包括顺铂和卡铂活性更低,但动物试验显示其可以对依托泊苷起到增效功能[28-33]。使用大量单一药物预处理的SCLC,顺铂和卡铂的总体有效率分别为15%和24%[28]。

接下来,有研究联合使用环磷酰胺与蒽环类抗生素(多柔比星或者表柔比星)和长春新碱(CAV或者CEV)。在广泛期中,CAV方案对SCLC具有14%的完全缓解率,57%总体有效率,中位生存时间为26周。在局限期中,CAV显示41%的完全缓解率,75%的总体有效率,中位生存时间为52周[8]。CAVE方案为CAV中增加了依托泊苷,并没有提高生存率,但是增加了血液毒性[34]。因此,直到1980年代中期,CAV才作为SCLC的一线标准化疗方案[34,35]。

对于有些患者,蒽环类抗生素是禁止使用的,主要是因为其可导致严重的心脏和肝脏功能异常,在临床前模型中推荐与最有活性的、具有协同作用的药物联合使用。VP-16或者依托泊苷联合顺铂方案的使用已产生令人满意的结果,总体有效率为86%~89%[29,30]。对之前蒽环类抗生素化疗耐药的患者,其总体有效率约为55%。局限期和广泛期中位生存时间分别为70周和43周[30,31]。在SCLC治疗上,本研究前所未有地证实了在体能状态差、严重的心脏疾病、广泛的肝脏和脑部转移的患者中应用联合化疗比单纯以蒽环类抗生素为基础的化疗具有显著的有效率[30,31]。

随后,直接将CAV和EP比较,显示两者具有同等的有效率(CAV的61%对比EP的51%)[36]。完全缓解率和中位生存率分别为10% vs. 7%和8.6个月 vs. 8.1个月[36]。同时调查表明:交替使用CAV和EP方案,除中位进展时间有延长趋势外(EP的4个月与EP/CAV的5.2个月),其他方面没有差别[36]。然而,FUKUOKA等在日本开展的相似研究显示EP或者CAP联合EP(CAV/EP)与CAV相比,具有显著的有效率(分别为78%、76%和55%)[37]。在生存率上,CAV/EP联合方案(11.8个月)也优于EP方案(9.9个月)(P=0.056)和CAV方案(9.9个月)(P=0.027)[37]。

后续5年随访的临床三期对照试验证实了这些支持含铂类方案的研究[38]。在LD-SCLC患者中,EP方案优于CEV方案,EP方案与CEV方案的2年和5年的生存率分别为25%和10%与8%和3%(P=0.0001)[38]。在ED-SCLC患者中,生存优势EP方案优于CEV方案,但其中位生存时间分别为8.4个月对比 6.5个月,两者无统计学差异[38]。当同步胸部放疗,EP方案与以蒽环类抗生素为基础的方案相比,具有更好的耐药性,例如减少了食管炎和肺炎,因此在SCLC化疗中得到更多的应用[10,22,30,31,37-40]。

日益广泛使用铂类化疗药物治疗实体瘤激起了大量研究,包括比较含铂方案与无铂方案,以及头对头比较含顺铂与含卡铂方案对肿瘤的治疗效果。Pujol等的Meta分析发现以顺铂为基础的化疗方案比没有顺铂的方案对SCLC治疗可能具有更高的有效率(HR 1.35;95%的可信区间:1.18-1.55)[41]。顺铂具有肾毒性、神经毒性和胃肠道不良反应,而卡铂的不良反应表现为骨髓抑制[42]。Rossi的COCIS Meta分析集中分析是否可以使用卡铂代替顺铂[42]。得出的结论是以顺铂为基础的化疗方案与以卡铂为基础的化疗方案在客观缓解率、无进展生存期和总生存期方面是相当的[42]。因此,为了避免非血液毒性,使用卡铂代替顺铂似乎是合理的。

一线化疗方案

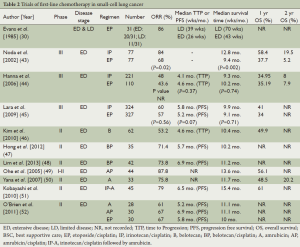

目前的联合化疗方案,无论EP或者sCAV方案,所能达到的部分或者完全缓解率为50%~85%,中位生存时间为9~12个月[4,10]。为了提高SCLC的治疗效果,鼓励研究一些证实在复发疾病中有初步结果的化疗药物。很多研究似乎都集中在DNA拓扑异构酶方面,它是一种DNA复制过程中和细胞生存至关重要的酶(表2)。DNA拓扑异构酶I和II抑制剂通过保持扭转应力可达到阻止DNA和RNA复制的过程,可以产生显著的细胞毒性,最终阻碍肿瘤细胞分裂[53]。

Full table

伊立替康

伊立替康是DNA拓扑异构酶I的抑制剂,大量的Ⅱ期试验结果显示出该药的疗效。日本的临床肿瘤研究小组(JCOG)进行了一项临床Ⅲ期试验,联合顺铂和伊立替康(IP)治疗ED-SCLC,并将其与EP方案进行比较[43]。该试验提前结束,因为期间分析显示IP方案在中位生存时间上显著优于EP方案(分别为12.8个月和9.4个月,P=0.002)[43]。两年的总体生存率分别为19.5%和5.2%,对ED-SCLC治疗是一个新的希望。与EP治疗方案中常见不良反应为骨髓抑制不同的是,IP常见不良反应为腹泻[43]。

同时,该治疗方案在日本将被作为一线治疗方案,在改变其他国家的标准治疗方案之前,需要做进一步的验证试验。北美两个大型的研究也进行了IP方案,但是和JCOG的研究的结果不一致[44,45]。第一个研究对化疗方案进行了细微的调整(在21天周期的1、8天,以顺铂30 mg/m2静脉滴注加伊立替康65 mg/m2静脉滴注);而JCOG方案为第1天使用顺铂60 mg/m2静脉滴注,分别在每28天的第1、8和15天使用伊立替康65 mg/m2静脉滴注,两者对改善生存无差别[44]。接下来SWOG S0124试验使用的方案与JCOG方案相同,结果发现IP在客观缓解率和总体生存率方面并不优于EP方案[45]。推测出现此情况可能的原因是不同的种族人群具有不同的药物基因组,这可能导致不同的结果,后面会进一步阐述这个概念。

贝洛替康

贝洛替康是一种新型喜树碱衍生物,它可以抑制拓扑异构酶I,在Ⅱ期临床试验中,在未经治疗的ED-SCLC中使用单一制剂显示阳性结果[46]。其客观缓解率达到53.2%,到达进展期的时间为4.6个月,中位总体生存期为10.4个月[46]。血液系统毒性反应最常见,其中3/4等级中性粒细胞减少达到71%[46]。随后,使用贝洛替康联合顺铂方案,两个临床Ⅱ期研究均显示客观缓解率≥70%,中位生存时间(MST)≥10个月[47,48]。正在进行的三期临床试验(COMBAT)的结果很被期待,因为其可以比较贝洛替康联合顺铂方案与金标准EP方案治疗SCLC的效果[54]。

氨柔比星

氨柔比星是一种合成的蒽环类抗生素衍生物,与阿霉素具有相同的结构特点,它可以稳定拓扑异构酶II-DNA复合物[55],其活性代谢物氨柔比星醇可以优先积累在肿瘤细胞中,这与降低其药物毒性相关,包括蒽环类抗生素相关的心脏毒性[53,56,57]。一项二期临床试验发现在未经治疗的ED-SCLC患者中,单独使用氨柔比星化疗可以使客观缓解率达到75.8%,中位生存期为11.7个月,两年生存率为20.2%[50]。

随后,研究发现氨柔比星用于一线含铂双药化疗得到的有效率和生存率比得上依托泊苷联合铂类药物方案。等进行的一项临床I~Ⅱ期临床试验,使用氨柔比星联合顺铂作为ED-SCLC的一线治疗方案,确定最大耐药剂量,推荐新的联合方案包括氨柔比星40 mg/m2/ d和卡铂60 mg/m2/ d[49]。使用推荐的给药方案,该研究报道ORR为87.8%(36/41),MST为13.6个月,1年生存率为56.1%,然而这些好的结果可能会被3/4级中性粒细胞减少的不良反应(95.1%)所抵消[49]。

日本西部胸部肿瘤研究组0301试验是一个Ⅱ期临床试验,该试验调查在既往治疗的ED-SCLC中先使用IP方案再使用氨柔比星的序贯三联化疗方案化疗效果[51]。该研究报道ORR为79%,中位PFS为6.5个月,中位OS为15.4个月,但是不良反应中骨髓抑制也很明显,达到3/4级中性粒细胞减少比例为91%,还有15%因为使用氨柔比星后中性粒细胞减少而导致发热[51]。

EORTC 08062的Ⅱ期随机临床试验选择非洲和亚洲人群,将单独使用氨柔比星(A)或者与顺铂(AP)联合使用,与标准的EP方案进行比较[52]。通过独立观察,发现A、AP和EP治疗方案的ORR分别为61%、67%和67%[52,58]。虽然,使用氨柔比星与血液系统≥3级的毒性反应具有显著的相关性,但是其令人兴奋的高有效率还是激起探讨其在SCLC疾病治疗中作用的进一步研究兴趣[52]。

最近,NORO等进行的一项临床Ⅱ期试验,每周交替使用无交叉耐药的AP和IP方案治疗ED-SCLC[59]。同时,该研究的ORR为85%,结果使人印象深刻,其中还包括20%的CR,但≥3级中性粒细胞比例为83.3%,骨髓抑制明显。然而,每周使用IP方案与腹泻显著相关。MST为359天(12个月),中位PFS为227天(7.5个月),1年的OS为40%[59]。因此,氨柔比星-顺铂(AP)联合使用或者交替使用AP与IP似乎是一个非常有效的治疗方案,目前,正在进行临床Ⅲ期试验比较AP和EP疗效[60]。

持续与巩固治疗

由于SCLC具有快速复发的特征,一般使用维持治疗策略来延长复发或进展时间。东部肿瘤合作研究组(ECOG)进行了一项Ⅲ期临床试验,(拓扑异构酶I抑制剂)对稳定期或者使用四个周期顺铂-依托泊苷治疗后有效的患者使用托泊替康进行维持治疗[61]。虽然PFS显著提高,但是患者生活质量没有显著改善,总体生存率和单独使用托泊替康没有显著差别(8.9个月 vs. 9.3个月,P=0.43)[61]。随后,Rossi等通过系统性回顾和Meta分析发现增加维持性化疗、干扰素和生物药物治疗对生存的帮助很小[62]。

二线化疗方案

虽然通常可以观察到最初的一线化疗方案的客观缓解,但是很少见到复发后中位OS 超过6个月的情况[63]。对于主要以铂类为基础的金标准化疗方案的一些其他疾病(例如妇科肿瘤),初始反应程度是肿瘤进展过程的一个合理可靠的预测指标。然而,由于通常用铂类的实际敏感性(即无铂应用间隔≥12个月)来定义此类疾病,很少适用于SCLC,以前针对SCLC的铂类敏感性分类相对模糊,反映本病病程极易进展。

20世纪80年代最初的报告定义患者化疗耐药为:要么一线化疗药物治疗过程中有进展,要么治疗结束后90天内有进展[64]。反过来,除此之外都被归类为 疾病“敏感”。此外,一些特殊的患者,开始的诱导化疗既有高的缓解率又有延长的> 6个月的无治疗时间(TFI),再使用同样的药物作为主要的治疗可以达到50%的有效率[65,66]。这些早期的研究有助于定义目前命名的“敏感性复发”(PFS> 3个月)、“耐药”(PFS<3个月)和“难治”(一线化疗药物治疗后进展)的SCLC[67]。然而,在许多文献中,越来越多的“难治性”和“耐药性”的定义可以互换使用。

对于二线细胞毒性策略,目前还没有达成最有效的治疗方案的共识。然而,有使用喜树碱作为一种标准治疗的倾向。托泊替康是FDA迄今为止专门批准设立的单一药物。与常用的组合治疗方法例如CAV比较,托泊替康可出现相等的有效率(24.3% vs. 18.3%,P=0.285)和中位生存率(TTP:13.3周vs. 12.3周,P=0.552;OS:25周 vs. 24.7周,P=0.795),但是能减缓一些症状,例如呼吸困难、声音嘶哑和乏力等[68]。此外,在最佳支持治疗(BSC)中增加口服托泊替康,在改善症状和显著提高OS方面明显优于单独使用BSC(25.9周vs. 13.9周)[69]。有趣的是,直接比较口服和静脉给药可以得出相同的有效率(18.3% vs. 21.9%)、中位OS(33 vs. 35周)和生活质量[70]。

单药紫杉醇[71]、伊立替康[72]、吉西他滨[73]和长春瑞滨会对SCLC复发患者具有一定疗效[74]。虽然这些单一治疗药物的有效率不如其与铂类药物联合,但是联合用药的获益往往被增加的毒性抵消[75-77]。然而,对于敏感性复发PFS >3个月的患者,以铂类为基础的二药联合是一种可能的治疗选择。这种方法由Garassino等进行的一项Meta分析所证实,其中包括161例SCLC患者使用EP化疗方案失败后再使用二线化疗方案[78]。在该研究中,根据铂类敏感性治疗,只有30名(18.6%)接受了铂类药物的试验。值得注意的是,这项研究中适用铂类与不适用铂类药物的患者相比,显示一个更好的ORR趋势(34.5% vs. 17.5%,P=0.06)和OS(9.2个月vs. 5.8个月,P=0.08)[78]。有趣的是,有30%难治性/耐药性患者再挑战使用铂类化疗可以受益(例如SD + PR)[78]。尽管有这些结果,但在敏感性复发和TFI >6个月这两种情况中使用铂类药物仍需慎重。

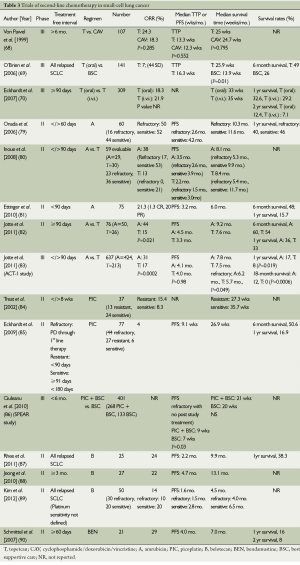

尽管这种方案小有成就,但应用当前细胞毒性药物进行二线或二线以上的治疗已达瓶颈。因此,研究的重点是开发新种类的药物,如铂盐、蒽环类药物、喜树碱和烷化剂,所有这些药物都是几十年来SCLC治疗的进步基石(表3)。

Full table

氨柔比星

前述含有氨柔比星的一线化疗方案的II / Ⅲ期研究结果令人鼓舞,激起了研究者对复发性SCLC治疗的很大兴趣。在这个领域,一些小的Ⅱ期临床试验同时对敏感性和难治性SCLC进行治疗[53](表3),这可能有助于建立一个代替拓扑替康的二线方案。

Onoda等在2006年发表的研究第一次强调氨柔比星具有补救治疗效果[79]。该项多中心Ⅱ期临床研究招募了60例复发性小细胞肺癌,包括16例难治性(即TTP<60天停止治疗)和44例敏感性(即证实第一线治疗有效和PD >60天治疗后停药)病例。为了与现有推荐剂量保持一致,单一使用氨柔比星每3周的第1~3天给药40 mg/m2。治疗周期中位数为4(范围:1~8个周期)。有趣的是,难治性和敏感性患者的ORR没有差别,分别为50%(95% CI,25-75%)和52%(95% CI,37%~68%)。然而,敏感性患者具有更高的PFS(2.6个月 vs. 4.2个月)、OS(10.3个月 vs. 11.6个月)和1年生存率(40% vs. 46%)[79]。关于毒性,3/4级骨髓抑制中最常见的是中性粒细胞减少症(83%)、其次是贫血(33%)和血小板减少(20%)。重要的是,只有3名患者(5%)经历了发热性中性粒细胞减少,无治疗相关性死亡[79]。

当然,这些发现也引发了随后的一项研究,即直接比较二线药物氨柔比星(每3周d1~3 40 mg/m2)和拓扑替康(每3周d1~5 1 mg/m2)的疗效。另一项日本的Ⅱ期临床研究由Inoue等人进行,包括先前接受铂类化疗的60例小细胞肺癌患者[80]。在59例可评估的患者中,包括23例难治性患者(定义为第一线治疗无有效或停药<90天后复发)和36例敏感性患者。氨柔比星(n=29)明显优于拓扑替康(n=30),表现在ORR分别为38%(95% CI:20%-56%)和13%(95% CI:1%-25%)。此外,根据患者敏感性(53% vs. 21%)或者难治性(17% vs. 0)进行分层也进一步突出这些优点[80]。虽然氨柔比星比拓扑替康主要具有PFS方面的优势(3.5个月 vs. 2.2个月),但这并没有影响到MST(8.1个月和8.4个月)。氨柔比星的中性粒细胞减少症(79% vs. 43%)、发热性中性粒细胞减少(14% vs. 3%)和非血液学毒性等级>3的比例明显增高,不幸的是,在这组患者中观察到继发性中性粒细胞减少后的死亡病例[80]。

已开始在亚洲人群中进行类似的治疗试验[例如IPASS与非小细胞肺癌(NSCLC)[91]]。因不同种族中某些药物基因组学等资料不同,这些队列研究的结果受到初始警告,可能需排除在白种人患者中出现相同反应的情况。具体而言,烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸(NADPH)氧化酶是一种精密地参与氨柔比星代谢的酶,亚洲人群中的该酶多态性可能影响药物的有效反应[92]。因而引起两项研究,将焦点放在应用氨柔比星二线方案治疗西方人群中难治性和敏感性小细胞肺癌患者。关于铂相关的难治性疾病,Ettinger等对75例患者进行了一线化疗后采用单剂氨柔比星治疗的Ⅱ期研究,取得了中位PFS为38天的结果[81]。其中,69例患者接受了中位4个周期的化疗(范围1~12周期),ORR为21.3%(95% CI,12.7%~32.3%)。此外,1例CR(1.3%)和15例的PR(20%)被证实PFS和OS分别为3.2个月(95% CI,2.4个月~4个月)和6个月(95% CI,4.8个月~7.1个月)[81]。有趣的是,其中的43名患者(57%)最初在以铂类为基础的治疗中没有获益,观察到ORR为16.3%(95%CI,6.8%~30.7%)[81]。

随后Jotte等研究在铂类敏感的小细胞肺癌(即TFI≥90天)中应用氨柔比星,并与含拓扑替康的方案(与Inoue试验相似)比较[82]。患者组(n=76)随机2∶1分配到氨柔比星组(n=50;每3周d1~3 40 mg/m2)或托泊替康组(n=26;每3周d1~5 1.5 mg/m2)。再次证实氨柔比星组较拓扑替康组的ORR得到显著提高(44% vs. 15%,P=0.021),这也被转换成较高的中位PFS(4.5个月vs. 3.3个月)和OS(9.2个月 vs. 7.6个月)。与Inoue的研究相反,氨柔比星比拓扑替康具有更高的骨髓抑制(≥3级)发生的趋势[82]。总之,研究结果证实氨柔比星更有利于敏感/难治性SCLC的ORR、PFS和OS,拓扑替康在亚洲人群的队列研究中显示比西方人群具有一定优势,从而促进了进一步大规模的研究。随机Ⅲ期ACT-1研究的目的是比较二线用药氨柔比星与拓扑替康在复发性SCLC患者中的疗效[83]。在本项试验中,637例患者随机2∶1分配到氨柔比星组(n=424)d1~3 40mg/m2和拓扑替康组(n=213)1.5静脉d1~5 1.5mg/m2。公布在2011年美国临床肿瘤学会(ASCO)年会上的结果证实,氨柔比星与托泊替康相比,可显著改善ORR(31% vs. 17%,P=0.0002),该研究与上述研究方案相似[83]。此外,尽管PFS、OS没有差异,但氨柔比星具有一定的优势趋势(HR 0.88;95%CI,0.73~1.06;P=0.17),在难治性病例的治疗中有特定的倾向(HR 0.77;95%CI,0.59~1.00;P=0.049)[83]。

另外,一些小的I / Ⅱ期研究探讨氨柔比星和托泊替康联合作为一个具有潜在疗效的二线化疗方案[93,94]。然而,尽管ORR能达到60%~70%,这些试验产生的任何乐观结果都会被一些不可接受的毒副反应所抵消,其中包括4级骨髓抑制、致命的腹泻和肺炎[94]。然而,大规模氨柔比星单药治疗研究的结果显示:氨柔比星单药治疗可以作为复发SCLC患者合理的替代治疗方案。

吡铂

吡铂(ZD0473)是一种专门开发的新颖有机铂类似物,为了避免一些含硫化合物(如谷胱甘肽)和金属硫蛋白对铂产生抵抗[95,96],可通过硫醇解毒剂与铂结合达到解毒作用[97]。硫醇的解毒属性除了围绕DNA烷基化的标准功能,使DNA链内和链间交联而促进细胞凋亡外,还具有抗肿瘤活性作用。更具体地说,体外研究已证实吡铂能够逆转SCLC细胞株H69和SBC-3对顺铂与卡铂的耐药性[98]。此外,逆转耐药相关的作用机制似乎与铂积累减少有关[98]。Treat等发表的临床报告最初确认了单剂活性的吡铂在复发性小细胞肺癌的治疗效果,其Ⅱ期研究对象为铂SCLC耐药患者(定义为PD<8周从第一线以铂类为基础的治疗,n=13)或敏感性患者(n=24)[84]。耐药组与敏感组ORR分别为15.4%和8.3%,中位OS分别为27.3周和35.7周的[84,96]。随后,更大规模的研究使用单剂吡铂(每个周期第3天150 mg/m2静脉给药 77 名复发SCLC),结果显示难治性疾病为57%(n=44)(铂为基础的治疗无效),35%为铂耐药(n=27)(即复发<90天完成一线铂为基础的治疗)和8%(n=6)铂类治疗敏感(即复发≥91天<180天完成一线铂类为基础的治疗后)[85]。对于难治性/耐药性患者在本研究中的优势是:ORR低至4%,中位PFS和OS分别为9.1周和26.9周[85]。对于副反应方面,最常见的3/4级毒性反应为血小板减少症(48%),其次为中性粒细胞减少(25%)和贫血(20%)。值得注意的是,没有发生发热性中性粒细胞减少的情况[85]。

上述这些研究都为复发患者使用吡铂治疗(SPEAR)奠定了基础[86]。第二阶段的研究包括401例复发性SCLC(<6个月完成的一线铂类为基础的化疗)随机以2∶1进行铂与最佳支持性治疗组(n=268)和单独使用最佳支持性治疗组(n=133)进行治疗。令人失望的是,该试验中铂与最佳支持性治疗组与单独使用最佳支持性治疗组相比未能显示任何生存优势(P=0.09)[86]。然而,这可以用最佳支持性治疗组的患者比例不平衡来解释。有趣的是,对本研究后未接受化疗的难治性患者(n=273)(即无有效或完成以铂类为基础第一线治疗<45天复发)亚组进行分析,发现吡铂对总计2周的PFS优势有统计学意义(P=0.03)[86]。但是奇怪的是,同样都是文献报道比较活跃的二线化疗设置,为什么BSC比托泊替康和氨柔比星更容易被选择使用?然而,随着肺肿瘤学家通过SPEAR试验的合理判断,这样的研究似乎不大可能永远不会实现。

贝洛替康

贝洛替康作为疗效比较温和的一线治疗的新型拓扑异构酶I抑制剂,也有一些小的研究使用该药在复发疾病中使用。Rhee等发表包括25例复发性SCLC(敏感性状态未知)Ⅱ期临床试验的结果,在治疗初始剂量为静脉滴注0.5 mg/m2 d1~5 q21 days [87]。根据毒性反应,只允许在随后的周期中进行一次适当剂量调整。在评估的21例患者中,有6例显示肿瘤客观有效,ORR为24%(意向性分析)。此外,中位PFS和OS分别为2.2个月和9.9个月,1年生存率为38.3%[87]。虽然3/4级中性粒细胞减少症的发病率特别高(88%),但严重的非血液学毒性并不普遍[87]。同样,另一个将贝洛替康用于27例使用铂和伊立替康为基础的一线治疗后3个月内复发的难治性疾病的单药研究[88],ORR为22%,中位PFS为4.7个月(95%CI,3.6个月~5.8个月),中位OS为13.1个月(95%CI,10.4个月~15.8个月)[88]。后者的结果特别有趣,因为它表明贝洛替康对于其他的拓扑异构酶I抑制剂有耐药的患者有一定的补救治疗作用。

最近Kim等人发表了较大的调查研究结果,即对50例敏感复发(n=20)或难治性小细胞肺癌(n=30)患者使用贝洛替康单药治疗的疗效[89]。ORR为14%(95%CI为4%-24%),中位随访期为4.2个月(范围0.1个月-19.2个月),中位PFS和OS分别为1.6个月和4.5个月。正如预期的那样,敏感性复发患者比其对应的难治性患者具有更好的ORR(20%vs. 10%)、OS(6.5个月 vs. 4.0个月,P=0.003)和PFS(2.8个月 vs. 1.5个月,P=0.053)。值得注意的是,多因素变异分析证实:肿瘤复发的类型和肿瘤对先前的化疗反应为OS的独立预后因素[89]。同样,3/4级骨髓抑制发生率最高的为中性粒细胞减少,其次是血小板减少症(38%)和贫血(32%)、中性粒细胞减少症(54%)[89]。此外,在本研究中记录了一例继发于败血症后死亡的病例。尽管贝洛替康有预期有害的不良反应,但作为二线化疗药物,对敏感和难治性SCLC都具有一定的活性,与氨柔比星相比,在这个特殊的领域值得进一步探讨。

未来的发展方向和结尾评论

以往有关突出的新型化疗药物的研究尽管短暂,但同时带来了一些乐观结果。最近,其他药物也脱颖而出,同样显示出不同程度的疗效。苯达莫司汀是一种双功能烷化剂,与卡铂联合用药,在ED-SCLC中表现出一定的活性。Koster等报道55名患者的ORR为72.7%,其中包括1例完全缓解患者。此外,中位TTP(5.2个月),MST(8.3个月)和毒性反应等相比毫不逊色于其他标准的一线含铂化疗方案[99]。苯达莫司汀也显示出对复发性SCLC(即TFI ≥60天有效)的敏感性,即ORR为29%,中位PFS和OS分别为4个月和7个月[90]。基于这个初步数据,目前进行的一项临床I/IIa研究正在积极招募30例SCLC ,使用苯达莫司汀与伊立替康联合化疗3个周期,随后再使用标准卡铂和鬼臼乙叉甙进行3个周期的化疗(临床试验政府标识符:NCT00856830)。

随着培美曲塞在治疗非小细胞肺癌(非鳞癌)和间皮瘤[100,101]方面的成功,已经尝试将其添加到SCLC的治疗方案中。然而,最近的两个用培美曲塞单药治疗(500 mg/m2和 900 mg/m2)敏感和难治性复发SCLC患者的Ⅱ期研究,仍不能充分确定其最小有效剂量[102,103]。这些已经确认的结果并不完全出乎意料。原始的Scagliotti研究培美曲塞治疗鳞状和非鳞状NSCLC的疗效区别[100],与胸苷酸合成酶(TS,培美曲塞的主要底物)的表达和鳞状上皮组织类型相关[104]。事实上,随后的研究进一步表明,较低的TS在晚期非鳞状NSCLC中的表达与PFS延长相关[105]。此外, SCLC(无论是切除的肿瘤还是细胞系)中TS的表达显著高于肺鳞癌和腺癌[106,107]。因此,会采取有悖常理的治疗策略,包括在SCLC治疗过程中使用TS抑制剂。

本篇综述一直试图勾勒出SCLC化疗的历史和目前的进展。铂与依托泊苷的二联用药仍然是一线治疗的金标准,目前正尝试切换成使用拓扑异构酶抑制剂,并证明其在改善生存方面具有战略意义。虽然伊立替康代替依托泊苷在JCOG研究中获得生存优势,但随后的SWOG S0124试验没有出现重复结果,目前的研究是将联合使用铂类和氨柔比星或贝洛替康与EP[52,54]疗效进行比较。同样,研究显示这些药品作为单剂都可以对敏感或难治性复发性疾病的患者进行补救治疗。考虑到FDA缺乏批准的小细胞肺癌二线治疗方案,对这些药物进行更大规模的临床试验就显得非常紧迫。此外,尽管SPEAR的研究成果令人沮丧,但是在避免耐药方面,仍有可能作为一种可行的顺铂或卡铂替代药物。因此,也可以考虑比较砒铂与其他的含铂二联方案用以治疗以前未经治疗的SCLC的效果。

和其他类型的实体瘤一样,本综述中概述的新型药物的组合最有可能用于进一步延长SCLC的生存期,如多靶点受体酪氨酸激酶抑制剂或阻止信号级联(例如抑制IGFR、mTOR的、MET和hedgehog信号传导)的其他药物,进而阻止SCLC的侵袭。这种联合疗法的大量临床前研究在于探究其药效和不可避免的耐药通路的上调。基于这些已有的研究,今后的临床试验仍需要更为有力的设计,来改变重大治疗策略以改变该疾病的惨淡前景。

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer 2010;127:2893-917. [PubMed]

- van Meerbeeck JP, Fennell DA, De Ruysscher DK. Small-cell lung cancer. Lancet 2011;378:1741-55. [PubMed]

- Kato Y, Ferguson TB, Bennett DE, et al. Oat cell carcinoma of the lung. A review of 138 cases. Cancer 1969;23:517-24. [PubMed]

- Pelayo Alvarez M, Gallego Rubio O, Bonfill Cosp X, et al. Chemotherapy versus best supportive care for extensive small cell lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;CD001990. [PubMed]

- Miller AB, Fox W, Tall R. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council comparative trial of surgery and radiotherapy for the primary treatment of small-celled or oat-celled carcinoma of the bronchus. Lancet 1969;2:501-5. [PubMed]

- Green RA, Humphrey E, Close H, et al. Alkylating agents in bronchogenic carcinoma. Am J Med 1969;46:516-25. [PubMed]

- Lowenbraun S, Bartolucci A, Smalley RV, et al. The superiority of combination chemotherapy over single agent chemotherapy in small cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 1979;44:406-13. [PubMed]

- Livingston RB, Moore TN, Heilbrun L, et al. Small-cell carcinoma of the lung: combined chemotherapy and radiation: a Southwest Oncology Group study. Ann Intern Med 1978;88:194-9. [PubMed]

- Hann CL, Ettinger DS. The change in pattern and pathology of small cell lung cancer. In: Govindan R. eds. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Alexandria, VA, 2009.

- Chute JP, Chen T, Feigal E, et al. Twenty years of phase III trials for patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: perceptible progress. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:1794-801. [PubMed]

- Shepherd FA, Crowley J, Van Houtte P, et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer lung cancer staging project: proposals regarding the clinical staging of small cell lung cancer in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the tumor, node, metastasis classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:1067-77. [PubMed]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Cancer Australia 2011. Lung cancer in Australia: an overview. Cancer series no. 64. Canberra: AIHW, 2011.

- Aupérin A, Arriagada R, Pignon JP, et al. Prophylactic cranial irradiation for patients with small-cell lung cancer in complete remission. Prophylactic Cranial Irradiation Overview Collaborative Group. N Engl J Med 1999;341:476-84. [PubMed]

- Fox W, Scadding JG. Medical Research Council comparative trial of surgery and radiotherapy for primary treatment of small-celled or oat-celled carcinoma of bronchus. Ten-year follow-up. Lancet 1973;2:63-5. [PubMed]

- Kalemkerian GP, Akerley W, Bogner P, et al. Small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11:78-98. [PubMed]

- Byers LA, Wang J, Nilsson MB, et al. Proteomic profiling identifies dysregulated pathways in small cell lung cancer and novel therapeutic targets including PARP1. Cancer Discov 2012;2:798-811. [PubMed]

- Rosell R, Wannesson L. A genetic snapshot of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Discov 2012;2:769-71. [PubMed]

- Haddadin S, Perry MC. History of small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2011;12:87-93. [PubMed]

- Barnard WG. The nature of the “oat-celled sarcoma” of the mediastinum. J Pathol 1926;29:241-4.

- Zelen M. Keynote address on biostatistics and data retrieval. Cancer Chemother Rep 3 1973;4:31-42. [PubMed]

- Lally BE, Urbanic JJ, Blackstock AW, et al. Small cell lung cancer: have we made any progress over the last 25 years? Oncologist 2007;12:1096-104. [PubMed]

- Johnson DH. Management of small cell lung cancer: current state of the art. Chest 1999;116:525S-530S. [PubMed]

- Watson WL, Berg JW. Oat cell lung cancer. Cancer 1962;15:759-68. [PubMed]

- Levine B, Weisberger AS. The response of various types of bronchogenic carcinoma to nitrogen mustard. Ann Intern Med 1955;42:1089-96. [PubMed]

- Wolf J, Spear P, Yesner R, et al. Nitrogen mustard and the steroid hormones in the treatment of inoperable bronchogenic carcinoma. Am J Med 1960;29:1008-16. [PubMed]

- Wolf J, Yesner R, Patno ME. Evaluation of nitrogen mustard in prolonging life of patients with bronchogenic carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Rep 1962;16:473-5. [PubMed]

- Medical Research Council Lung Cancer Working Party. Radiotherapy alone or with chemotherapy in the treatment of small-cell carcinoma of the lung. Br J Cancer 1979;40:1-10. [PubMed]

- Joss RA, Cavalli F, Goldhirsch A, et al. New drugs in small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 1986;13:157-76. [PubMed]

- Goldhirsch A, Joss R, Cavalli F, et al. Etoposide as single agent and in combination chemotherapy of bronchogenic carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev 1982;9:85-90. [PubMed]

- Evans WK, Shepherd FA, Feld R, et al. VP-16 and cisplatin as first-line therapy for small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1985;3:1471-7. [PubMed]

- Evans WK, Shepherd FA, Feld R, et al. First-line therapy with VP-16 and cisplatin for small-cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol 1986;13:17-23. [PubMed]

- Loehrer PJ Sr, Einhorn LH, Greco FA. Cisplatin plus etoposide in small cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol 1988;15:2-8. [PubMed]

- Cavalli F, Sonntag RW, Jungi F, et al. VP-16-213 monotherapy for remission induction of small cell lung cancer: a randomized trial using three dosage schedules. Cancer Treat Rep 1978;62:473-5. [PubMed]

- Jett JR, Everson L, Therneau TM, et al. Treatment of limited-stage small-cell lung cancer with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine with or without etoposide: a randomized trial of the North Central Cancer Treatment Group. J Clin Oncol 1990;8:33-8. [PubMed]

- Seifter EJ, Ihde DC. Therapy of small cell lung cancer: a perspective on two decades of clinical research. Semin Oncol 1988;15:278-99. [PubMed]

- Roth BJ, Johnson DH, Einhorn LH, et al. Randomized study of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine versus etoposide and cisplatin versus alternation of these two regimens in extensive small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial of the Southeastern Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:282-91. [PubMed]

- Fukuoka M, Furuse K, Saijo N, et al. Randomized trial of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine versus cisplatin and etoposide versus alternation of these regimens in small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1991;83:855-61. [PubMed]

- Sundstrøm S, Bremnes RM, Kaasa S, et al. Cisplatin and etoposide regimen is superior to cyclophosphamide, epirubicin, and vincristine regimen in small-cell lung cancer: results from a randomized phase III trial with 5 years’ follow-up. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:4665-72. [PubMed]

- Shaw EG, Frytak S, Eagan RT, et al. Etoposide-cisplatin and thoracic radiation therapy salvage of incomplete responders to a noncisplatin induction regimen for limited and extensive small-cell carcinoma of the lung. Am J Clin Oncol 1996;19:154-8. [PubMed]

- Skarlos DV, Samantas E, Kosmidis P, et al. Randomized comparison of etoposide-cisplatin vs. etoposide-carboplatin and irradiation in small-cell lung cancer. A Hellenic Co-operative Oncology Group study. Ann Oncol 1994;5:601-7. [PubMed]

- Pujol JL, Carestia L, Daurès JP. Is there a case for cisplatin in the treatment of small-cell lung cancer? A meta-analysis of randomized trials of a cisplatin-containing regimen versus a regimen without this alkylating agent. Br J Cancer 2000;83:8-15. [PubMed]

- Rossi A, Di Maio M, Chiodini P, et al. Carboplatin- or cisplatin-based chemotherapy in first-line treatment of small-cell lung cancer: the COCIS meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:1692-8. [PubMed]

- Noda K, Nishiwaki Y, Kawahara M, et al. Irinotecan plus cisplatin compared with etoposide plus cisplatin for extensive small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;346:85-91. [PubMed]

- Hanna N, Bunn PA Jr, Langer C, et al. Randomized phase III trial comparing irinotecan/cisplatin with etoposide/cisplatin in patients with previously untreated extensive-stage disease small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:2038-43. [PubMed]

- Lara PN Jr, Natale R, Crowley J, et al. Phase III trial of irinotecan/cisplatin compared with etoposide/cisplatin in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: clinical and pharmacogenomic results from SWOG S0124. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2530-5. [PubMed]

- Kim SJ, Kim JS, Kim SC, et al. A multicenter phase II study of belotecan, new camptothecin analogue, in patients with previously untreated extensive stage disease small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2010;68:446-9. [PubMed]

- Hong J, Jung M, Kim YJ, et al. Phase II study of combined belotecan and cisplatin as first-line chemotherapy in patients with extensive disease of small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:215-20. [PubMed]

- Lim S, Cho BC, Jung JY, et al. Phase II study of camtobell inj. (belotecan) in combination with cisplatin in patients with previously untreated, extensive stage small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2013;80:313-8. [PubMed]

- Ohe Y, Negoro S, Matsui K, et al. Phase I-II study of amrubicin and cisplatin in previously untreated patients with extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2005;16:430-6. [PubMed]

- Yana T, Negoro S, Takada M, et al. Phase II study of amrubicin in previously untreated patients with extensive-disease small cell lung cancer: West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group (WJTOG) study. Invest New Drugs 2007;25:253-8. [PubMed]

- Kobayashi M, Matsui K, Iwamoto Y, et al. Phase II study of sequential triplet chemotherapy, irinotecan and cisplatin followed by amrubicin, in patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer: West Japan Thoracic Oncology Group Study 0301. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1075-80. [PubMed]

- O’Brien ME, Konopa K, Lorigan P, et al. Randomised phase II study of amrubicin as single agent or in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin etoposide as first-line treatment in patients with extensive stage small cell lung cancer - EORTC 08062. Eur J Cancer 2011;47:2322-30. [PubMed]

- Kimura T, Kudoh S, Hirata K. Review of the management of relapsed small-cell lung cancer with amrubicin hydrochloride. Clin Med Insights Oncol 2011;5:23-34. [PubMed]

- Chonnam National University Hospital. Trial of belotecan/cisplatin in chemotherapy naive small cell lung cancer patient (COMBAT). In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000- [cited 2013 July 9]. Available online:

- Hanada M, Mizuno S, Fukushima A, et al. A new antitumor agent amrubicin induces cell growth inhibition by stabilizing topoisomerase II-DNA complex. Jpn J Cancer Res 1998;89:1229-38. [PubMed]

- Metro G, Duranti S, Fischer MJ, et al. Emerging drugs for small cell lung cancer--an update. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs 2012;17:31-6. [PubMed]

- Higashiguchi M, Suzuki H, Hirashima T, et al. Long-term amrubicin chemotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 2012;32:1423-7. [PubMed]

- Pignon JP, Arriagada R, Ihde DC, et al. A meta-analysis of thoracic radiotherapy for small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 1992;327:1618-24. [PubMed]

- Noro R, Yoshimura A, Yamamoto K, et al. Alternating chemotherapy with amrubicin plus cisplatin and weekly administration of irinotecan plus cisplatin for extensive-stage small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res 2013;33:1117-23. [PubMed]

- Sumitomo Pharmaceutical (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. Phase 3 study of amrubicin with cisplatin versus etoposide-cisplatin for extensive disease small cell lung cancer. In: ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000- [cited 2013 July 10]. Available online:

- Schiller JH, Adak S, Cella D, et al. Topotecan versus observation after cisplatin plus etoposide in extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer: E7593--a phase III trial of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2114-22. [PubMed]

- Rossi A, Garassino MC, Cinquini M, et al. Maintenance or consolidation therapy in small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer 2010;70:119-28. [PubMed]

- Davies AM, Evans WK, Mackay JA, et al. Treatment of recurrent small cell lung cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2004;18:387-416. [PubMed]

- Giaccone G, Donadio M, Bonardi G, et al. Teniposide in the treatment of small-cell lung cancer: the influence of prior chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1988;6:1264-70. [PubMed]

- Postmus PE, Berendsen HH, van Zandwijk N, et al. Retreatment with the induction regimen in small cell lung cancer relapsing after an initial response to short term chemotherapy. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1987;23:1409-11. [PubMed]

- Giaccone G, Ferrati P, Donadio M, et al. Reinduction chemotherapy in small cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol 1987;23:1697-9. [PubMed]

- Glisson BS. Recurrent small cell lung cancer: update. Semin Oncol 2003;30:72-8. [PubMed]

- von Pawel J, Schiller JH, Shepherd FA, et al. Topotecan versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and vincristine for the treatment of recurrent small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:658-67. [PubMed]

- O’Brien ME, Ciuleanu TE, Tsekov H, et al. Phase III trial comparing supportive care alone with supportive care with oral topotecan in patients with relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5441-7. [PubMed]

- Eckardt JR, von Pawel J, Pujol JL, et al. Phase III study of oral compared with intravenous topotecan as second-line therapy in small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:2086-92. [PubMed]

- Smit EF, Fokkema E, Biesma B, et al. A phase II study of paclitaxel in heavily pretreated patients with small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 1998;77:347-51. [PubMed]

- Masuda N, Fukuoka M, Kusunoki Y, et al. CPT-11: a new derivative of camptothecin for the treatment of refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1992;10:1225-9. [PubMed]

- Masters GA, Declerck L, Blanke C, et al. Phase II trial of gemcitabine in refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial 1597. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1550-5. [PubMed]

- Furuse K, Kubota K, Kawahara M, et al. Phase II study of vinorelbine in heavily previously treated small cell lung cancer. Japan Lung Cancer Vinorelbine Study Group. Oncology 1996;53:169-72. [PubMed]

- Goto K, Sekine I, Nishiwaki Y, et al. Multi-institutional phase II trial of irinotecan, cisplatin, and etoposide for sensitive relapsed small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2004;91:659-65. [PubMed]

- Fujita A, Takabatake H, Tagaki S, et al. Combination of cisplatin, ifosfamide, and irinotecan with rhG-CSF support for the treatment of refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer. Oncology 2000;59:105-9. [PubMed]

- Groen HJ, Fokkema E, Biesma B, et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin in the treatment of small-cell lung cancer patients resistant to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide: a non-cross-resistant schedule. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:927-32. [PubMed]

- Garassino MC, Torri V, Michetti G, et al. Outcomes of small-cell lung cancer patients treated with second-line chemotherapy: a multi-institutional retrospective analysis. Lung Cancer 2011;72:378-83. [PubMed]

- Onoda S, Masuda N, Seto T, et al. Phase II trial of amrubicin for treatment of refractory or relapsed small-cell lung cancer: Thoracic Oncology Research Group Study 0301. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:5448-53. [PubMed]

- Inoue A, Sugawara S, Yamazaki K, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing amrubicin with topotecan in patients with previously treated small-cell lung cancer: North Japan Lung Cancer Study Group Trial 0402. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5401-6. [PubMed]

- Ettinger DS, Jotte R, Lorigan P, et al. Phase II study of amrubicin as second-line therapy in patients with platinum-refractory small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:2598-603. [PubMed]

- Jotte R, Conkling P, Reynolds C, et al. Randomized phase II trial of single-agent amrubicin or topotecan as second-line treatment in patients with small-cell lung cancer sensitive to first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:287-93. [PubMed]

- Von Pawel J, Jotte R, Spigel DR, et al. Randomized phase 3 trial of amrubicin versus topotecan as second-line treatment for small cell lung cancer (SCLC). J Clin Oncol 2011;29:abstr 7000.

- Treat J, Schiller J, Quoix E, et al. ZD0473 treatment in lung cancer: an overview of the clinical trial results. Eur J Cancer 2002;38:S13-8. [PubMed]

- Eckardt JR, Bentsion DL, Lipatov ON, et al. Phase II study of picoplatin as second-line therapy for patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2046-51. [PubMed]

- Ciuleanu T, Samarzjia M, Demidchik Y, et al. Randomized phase III study (SPEAR) of picoplatin plus best supportive care (BSC) or BSC alone in patients (pts) with SCLC refractory or progressive within 6 months after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:abstr 7002.

- Rhee CK, Lee SH, Kim JS, et al. A multicenter phase II study of belotecan, a new camptothecin analogue, as a second-line therapy in patients with small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2011;72:64-7. [PubMed]

- Jeong J, Cho BC, Sohn JH, et al. Belotecan for relapsing small-cell lung cancer patients initially treated with an irinotecan-containing chemotherapy: a phase II trial. Lung Cancer 2010;70:77-81. [PubMed]

- Kim GM, Kim YS, Ae Kang Y, et al. Efficacy and toxicity of belotecan for relapsed or refractory small cell lung cancer patients. J Thorac Oncol 2012;7:731-6. [PubMed]

- Schmittel A, Knödler M, Hortig P, et al. Phase II trial of second-line bendamustine chemotherapy in relapsed small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer 2007;55:109-13. [PubMed]

- Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med 2009;361:947-57. [PubMed]

- Ettinger DS. Amrubicin for the treatment of small cell lung cancer: does effectiveness cross the Pacific? J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:160-5. [PubMed]

- Shibayama T, Hotta K, Takigawa N, et al. A phase I and pharmacological study of amrubicin and topotecan in patients of small-cell lung cancer with relapsed or extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2006;53:189-95. [PubMed]

- Nogami N, Hotta K, Kuyama S, et al. A phase II study of amrubicin and topotecan combination therapy in patients with relapsed or extensive-disease small-cell lung cancer: Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group Trial 0401. Lung Cancer 2011;74:80-4. [PubMed]

- Holford J, Sharp SY, Murrer BA, et al. In vitro circumvention of cisplatin resistance by the novel sterically hindered platinum complex AMD473. Br J Cancer 1998;77:366-73. [PubMed]

- William WN Jr, Glisson BS. Novel strategies for the treatment of small-cell lung carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2011;8:611-9. [PubMed]

- Mistry P, Kelland LR, Abel G, et al. The relationships between glutathione, glutathione-S-transferase and cytotoxicity of platinum drugs and melphalan in eight human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Br J Cancer 1991;64:215-20. [PubMed]

- Tang CH, Parham C, Shocron E, et al. Picoplatin overcomes resistance to cell toxicity in small-cell lung cancer cells previously treated with cisplatin and carboplatin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2011;67:1389-400. [PubMed]

- Köster W, Heider A, Niederle N, et al. Phase II trial with carboplatin and bendamustine in patients with extensive stage small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:312-6. [PubMed]

- Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3543-51. [PubMed]

- Vogelzang NJ, Rusthoven JJ, Symanowski J, et al. Phase III study of pemetrexed in combination with cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:2636-44. [PubMed]

- Socinski MA, Raju RN, Neubauer M, et al. Pemetrexed in relapsed small-cell lung cancer and the impact of shortened vitamin supplementation lead-in time: results of a phase II trial. J Thorac Oncol 2008;3:1308-16. [PubMed]

- Jalal S, Ansari R, Govindan R, et al. Pemetrexed in second line and beyond small cell lung cancer: a Hoosier Oncology Group phase II study. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:93-6. [PubMed]

- Ceppi P, Volante M, Saviozzi S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung compared with other histotypes shows higher messenger RNA and protein levels for thymidylate synthase. Cancer 2006;107:1589-96. [PubMed]

- Nicolson MC, Fennell DA, Ferry D, et al. Thymidylate Synthase Expression and Outcome of Patients Receiving Pemetrexed for Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer in a Prospective Blinded Assessment Phase II Clinical Trial. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:930-939. [PubMed]

- Ibe T, Shimizu K, Nakano T, et al. High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung shows increased thymidylate synthase expression compared to other histotypes. J Surg Oncol 2010;102:11-7. [PubMed]

- Monica V, Scagliotti GV, Ceppi P, et al. Differential Thymidylate Synthase Expression in Different Variants of Large-Cell Carcinoma of the Lung. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:7547-7552. [PubMed]

(译者:谢而付;校对:邵明海)

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)