Assets and needs of respiratory patient organizations: differences between developed and developing countries

The worldwide burden of chronic respiratory diseases (CRDs) is alarming. 63% of deaths are caused by Non Communicable Diseases (NCD). 80% of these global deaths are in the low and middle income countries. 90% percent of death from Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is in the developing countries according to WHO Global Status of Chronic Diseases 2010 (1). We must increase our efforts to deal with CRDs worldwide and especially in developing countries!

Health care professionals (HCPs) engage in practice to try to cure patients or in the case of chronic diseases to manage their diseases. Studies confirm the importance and cost efficiency of having patients involved in making decisions about their own care. Otherwise non-compliant patients are a frequent and costly consequence, when they do not understand the decisions made by their physicians. HCPs often do not have the time to explain everything in detail in the terminology their patients can understand to reach agreement on joint decisions with the patient.

Therefore patient organizations (POs) and self-help groups become increasingly important. For example, asthma and allergy POs have existed in Europe for 116 years (Deutscher Allergie und Asthma Bund founded in 1897) and in the US for 105 years (American Lung Association, founded in 1907). This idea is spreading in all continents, and it is important to assist the pioneers working in emerging countries to create powerful POs to be equal partners with HCP organizations and governments, and to be involved in decision-making from first discussions to final decisions.

European academic groups refer to “emerging countries” rather than “developing countries.” The meaning is similar and probably clearer in the European description.

POs traditionally focus on chronic and rare diseases. Patients joining a PO show interest in their disease and want to control it so POs can help to empower patients. Empowered patients are more willing to feel responsible for their therapy. Patients who feel responsible want to understand therapeutic opportunities and request education. Educated patients are able to adhere to their doctors’ advice with the decision arrived at by mutual agreement.

POs are usually founded by patients, care-givers, and HCPs, who mainly work as volunteers; These groups also work to build their membership. More than half of the POs in central Europe have a defined legal status. Their communication channels are member meetings, information exchange by calls, publications, e-mails, general constitutional meetings and their own websites.

POs mainly work on the support of joint activities, individual support, education and dissemination of information, advocacy and online activities. They see their effectiveness in the INCREASE of:

- disease specific knowledge;

- own daily handling/management of the disease;

- self-confidence;

- improving activities of daily life;

- social contacts (decrease of isolation);

- general health.

International COPD Coalition (ICC), and Global Asthma Allergy Patient Platform (GAAPP) believe that POs with common interests, such as respiratory care, should work together in advancing efforts to benefit their patient members. We have collaborated in performing a survey of the presence and the activities of respiratory POs worldwide to help our organizations target our efforts to strengthen national respiratory POs and better serve their patient members. We are grateful to the ICC and GAAPP members as well as to the responses of the members of WHO’s Global Alliance Against Chronic Respiratory Diseases (GARD) who responded to the survey. The survey focused on the activities and differences between respiratory POs from developed and developing countries. In addition to questions about POs we included questions about curriculum in universities and the training of primary care HCPs (Physicians and nurses) and the role of professional organizations, health authorities, and health care settings for patient education. The countries represented in the survey, the statistical outcomes of the responses received, and our interpretation of the results are reported in this article in the ICC Column of the Journal of Thoracic Disease.

Data from the survey

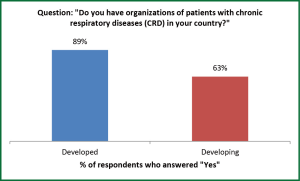

There are many differences in respiratory POs in developed as opposed to developing countries, and these differences identify the activities that are needed for the global respiratory POs for COPD (International COPD Coalition; ICC; www.internationalcopd.org) and for asthma/allergy (Global Asthma Allergy Patient Platform, GAAPP; www.ga2p2.org). Table 1 has a list of the responding developed and developing countries and the number of respondents from each. Although 89% of developed countries surveyed have organizations of patients with CRDs, only 63% of developing countries have such groups (Figure 1). Clearly, work needs to be done in developing countries, and materials and organizational assistance provided to patient advocates in these countries.

Full table

When asked why many developing countries do not have patient groups the responses were:

- We don’t know about such organizations;

- Sustainability is difficult without funding;

- Patients are too tired to attend meetings;

- Underdiagnosis of CRDs is rampant;

- Diversity of language;

- Groups led by physicians handle much of the education;

- No motivation from the government.

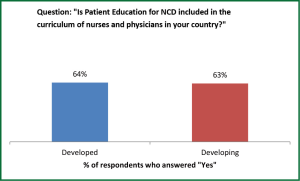

Education of physicians and nurses in training concerning Patient partnership for NCD management is present in the curricula of 67% of developed and 63% of developing countries (Figure2). One third of both groups of countries have deficiencies in providing their physicians in training this needed information to care for respiratory NCD patients.

The lack of knowledge by HCPs concerning CRDs and lack of patient education was explained in these ways:

- Professors are not knowledgeable about educating patients;

- There is very little continuing medical education for physicians;

- Physicians must do private work because salaries in the public institutions are low;

- Lack of referral for education in the health system;

- Communicable diseases have the highest priority in the national agenda.

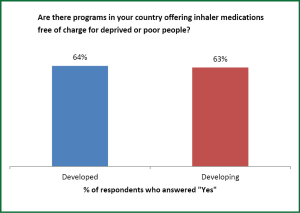

Inhaled medications are available in 100% of both developed and developing countries. Free respiratory medications for needy patients are available in about two-thirds of both developed and developing countries, which is encouraging but which still leaves many patients unable to obtain needed medication (Figure 3).

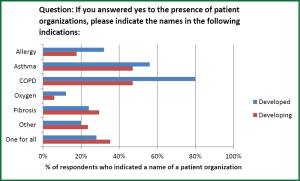

Figure 4 shows the percentage of POs focused on various respiratory conditions in developed and developing countries. Although there is room for improvement in both, there is a startling disparity in the absence of COPD patient groups in developing countries compared to developed countries (80% vs. 47%), which also accounts for the difference seen in Figure 1 and emphasized the need for ICC and its member organizations efforts in support of patients in developing countries.

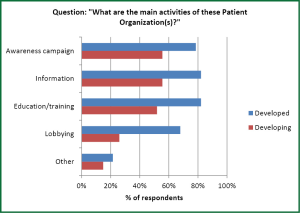

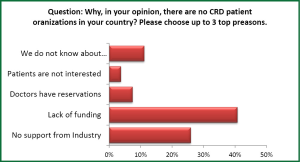

Figure 5 shows the activities of respiratory patient groups in different areas. There is no significant difference between the activities in developed and developing countries in disease education, training, information and awareness, but much less lobbying in developing countries (68% vs. 26%). This finding could be the result of fewer resources both for the respiratory POs and their governments, but since lobbying can be beneficial for patients and is not necessarily expensive, global respiratory organizations should assist developing countries in their advocacy activities. As shown in Figure 6, the main reason for the absence of patient CRD organizations in countries is lack of funding. However, many countries are simply not well informed about POs, and in other countries regional disparities may deprive patients of representation.

A surprising finding is in the provision of educational programs in countries’ poverty areas. Very few programs are held in these high need areas in developing countries. Developing countries do a better job at this. Can it be that poor people fare worse in rich countries than in poor? Certainly it is a message for respiratory patient groups in developed countries. Educational programs for COPD are available in 25% of developed countries and in 48% of developing countries. For asthma 39% of developed countries and 63% of developing countries have programs. It may be that WHO educational programs, such as the Practical Approach to lung health (PAL) program, and the “Package of essential non-communicable disease interventions (PEN) for primary health care in low-resource settings (6,7)”. Provide this needed assistance in low income countries.

In assessing which medical groups provide education to respiratory patients in developed and developing countries, specialist and primary care physicians, nurses, and hospitals all participated actively. However, needed disease education, which is provided by respiratory patients’ organizations in 79% of developed countries is only provided by 17% of respiratory POs in developing countries–a shocking disparity. Clearly, providing user-friendly, translated, educational materials for developing countries will be a priority for ICC and GAAPP, but our work alone will not supply the needed education if we do not involve local experts and their judgment about what is needed. Materials need to be translated and adapted to cultural and economic conditions. The extensive use of the Arabic kit for COPD (available at www.internationalcopd.org) was made possible by diverse expert opinion. The presence of multi-ethnicity requires that transcultural curricula be made available for patient education to succeed (2-5).

New concepts of patient education and advocacy in developing countries

The burden of CRDs is alarming worldwide, 6.8% of deaths in women and 6.9% in men were caused by CRDs (1).

Partnership and education of patients is a needed component of COPD and asthma management (2,3), but in developing countries, CRD care is emergency oriented, while follow-up and long-term preventive management are lacking (4,5). Education of patients is recommended at all levels of health care from specialist to primary care, but patients can also be assisted by various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) working with the World Health Organization. The United Nations has recommended that HCPs promote the capacity-building of non-communicable disease-related NGOs at the national level to establish a social movement to confront non-communicable diseases and realize their full potential as partners in the prevention and control of such diseases. The WHO supports patient education with an emphasis on community action to provide equity of care (6-8).

In our opinions as leaders of ICC and GAAPP, education of patients about CRDs by busy specialists and crowded primary care practices, particularly in developing countries, is scarce. Our survey supports this point of view. We believe that patient groups working with HCPs need to be established to help patients with these conditions to cope with their disease and these patient groups should advocate for the ICC COPD patient’s bill of rights, which defends their rights for early diagnosis, risk factor avoidance, adequate treatment and social integration (available from www.internationalcopd.org).

Let us provide some examples from developing countries. If we take the experience of Ho-chi-minh City, Vietnam (8), the national respiratory society founded and sponsors a respiratory patient club. The patient club meets monthly with a lecture of a doctor and very detailed discussions. There are examinations every three months to evaluate the knowledge of patients. The club leaders and members visit patients if they are hospitalized, and for severely ill patients or when a member dies, they give gifts and organize outings. The club organizes annual meetings, elects executive committee members, and issues a journal yearly. They have a musical group.

In Turkey there is a similar patient group supervised by Turkish Respiratory Society (8).

In Syria, being a member of the ICC, Tishreen University created a committee for education of asthma and COPD in collaboration with MOH, and Syrien Universities. Educational materials for patient education were prepared and delivered to workers in factories and schools, throughout Syria. Last year a civil society for patients suffering from CRDs, was officially created in the coastal region. Members are patients, physicians, and volunteers. Our mission is to educate and help. The pharmaceutical industry helps this effort by providing free medications.

Patient Micro-Organizations

We suggest a foundation for CRD POs by educating patients in all health care settings, which we would call Patient Micro-Organizations. This approach is suitable for developing countries to overcome, economic, social, and administrative barriers preventing the creation of nationwide POs. They would function to train HCPs to educate patients and their families. The families would then be integrated into providing COPD and asthma/allergy care. A foundation of Patient Micro-Organizations would promote the establishment of full national POs that can advocate at the national level with health ministries.

We believe there should be guides for HCPs that illustrates tools and steps to work with patients, to involve them in education and care. Patient education and organization should be started from the ground level and move upward. These Patient Micro-Organizations should be part of the existing health care structures (e.g., hospitals, health centers, pharmacies, and nursing schools). With the guides for education, trainers would meet and be trained. Then, workshops would educate patients in small interactive groups with case examples presented.

Four steps would need to be taken:

- Prepare Tools. Key messages about the essentials of their disease and its care would be provided either in hard copies or electronically depending on the level of education and culture. Photos or videos would be provided for illiterate patients;

- Medical staff would integrate these tools in their knowledge and training materials, and universities would integrate it into their curriculum;

- Key messages should then be delivered to patients as part of medical care by HCPs. Sessions for groups of patients would be supervised by primary care practitioners or by trainees, post graduate medical students, and nurses;

- Audits and feed-back for evaluation of each of the three steps are mandatory.

To implement these Patient Micro-Organizations, CRD HCPs should address health authorities directly, and collaborate with multiple sectors of the health care system: higher education, military health services, professional societies, NGOS, social organisations, like women’s or youth groups, as well as other sectors, depending on the health care system of each country (5). These Micro-Organizations could be integrated with the Global Alliance of CRDs/WHO programs (8) as well as other non-communicable diseases programmes (6,7).

Patients must work with HCPs in all elements of these Patient Micro-Organizations. Patients need to be involved throughout the process of making health care decisions. If they are not involved then they do not “own” their own health care and without this “ownership” they will not accept and participate in the health care.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. eds. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010.

- Car J, Partridge MR. Crosscultural communication in those with airway diseases. Chron Respir Dis 2004;1:153-60. [PubMed]

- Burney P, Potts J, Aït-Khaled N, et al. A multinational study of treatment failures in asthma management. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:13-8. [PubMed]

- United Nations General assembly September 2012, Sixty-seventh session.

- Strunk RC, Ford JG, Taggart V. Reducing disparities in asthma care: priorities for research--National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop report. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;109:229-37. [PubMed]

- Practical Approach to Lung Health-Manual on initiating PAL implementation. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

- Package of essential non-communicable disease interventions (PEN) for primary health care in low-resource settings. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. c2010. Available online: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/ publications/2010/9789241598996_eng.pdf

- GARD meeting report 2012. Available online: www.who.int/gard/li>