Neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus

Introduction

Primary neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus (NETTs) have been described for the first time by Rosai and Higa in 1972 (1). NETTs were exceedingly rare neoplasms, accounting for approximately 0.4% of all carcinoid tumors (2) and less than 5% of all the anterior mediastinal neoplasms (3). An age-adjusted incidence rate of 0.18 per 1,000,000 persons in the United States, with a male predominance (male-to-female ratio, 3:1), was recently observed (4).

Unlike neuroendocrine tumors arising from the gastro-enteropancreatic tract or from the lung, NETTs presented with a very aggressive biological behavior. Furthermore, it has been found that these neoplasms are malignant in more than 80% of cases, as opposed to lung carcinoids, which are regarded as malignant in approximately 25% of cases, only (5).

According to the 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) tumors classification (6), NETTs still continue to be included in the thymic carcinoma group (7,8), and were classified into 4 histological entities, in 2 major histopathological types: well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (typical and atypical carcinoids) and poorly differentiated ones (small-cell and large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas).

Since the first report, no more than 400 NETTs cases have been reported in the literature: the majority were case reports, and only few articles reported modest series from single Institutions. The majority of these were too small to provide uniform assessment and validated prognostic factors for these uncommon neoplasms. Recently, two papers were based on large retrospective databases (4,9); therefore, more data were available about clinical variables influencing survival and recurrence development.

Clinical features and treatment

NETTs were predominantly located in the anterior mediastinal space (very rarely they presented in the middle or posterior mediastinum), and showed a particular predilection for men, typically in their fourth/fifth decades of life (9).

Filosso et al. (10) reported a limited percentage of NETTs patients (8.3%) with a history of synchronous/metachronous second cancer, in contrast to thymomas, in which up to 24% of cases had a second tumor.

From the clinical point of view, NETTs may manifest as follows: (I) asymptomatic, incidentally found performing a chest X-ray for other reasons (in approximately one third of cases); (II) with symptoms caused by thoracic/mediastinal structures displacement/compression/invasion; (III) associated with endocrinopathies or (IV) with symptoms caused by distant metastases, usually liver, brain, lung or bone (in approximately 20% of patients).

Thoracic and mediastinal symptoms varied according to the extent of the lesion, and it may range from chest pain, cough, dyspnea to superior vena cava syndrome (in approximately 20% of cases), to hoarseness, laringeal nerve invasion, hemidiaphragm lifting, caused by phrenic nerve involvement.

About 50% of NETTs patients presented with a lymph-nodal involvement at the time of surgical resection, but this condition was not found to be associated with a poor outcome.

Almost 50% of NETTs were functional and were associated with endocrinopaties, the most common of which were Cushing’s syndrome (adrenocorticotropic hormone-ACTH-ectopic production), acromegaly (growth hormone releasing hormone-GH-RH-hypersecretion) and hypertropic osteoarthropaty (11). Multiple endocrine neoplasia-1 (MEN-1) syndrome (Wermer syndrome) was seen in 19% to 25% of NETTs; this tumor represents the major cause of death in MEN-1 patients (11). Finally, myasthenia gravis (MG), which was the most common paraneoplastic syndrome in thymomas, has been incidentally described in a man with NETT (12), whilst carcinoid syndrome was very rarely observed.

NETTs radiological diagnostic workup usually included chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT) scan. The somatostatin receptors presence in the neoplastic tissue justified the use of 111-Indium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid-D-phenylalanine-octreotide (Octreoscan) scintigraphy, both in preoperative and in follow-up settings.

18FDG PET scan very often was positive, especially in case of large, locally aggressive and with high-proliferation index tumors. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was commonly recommended to rule out possible tumor invasion in adjacent mediastinal structures.

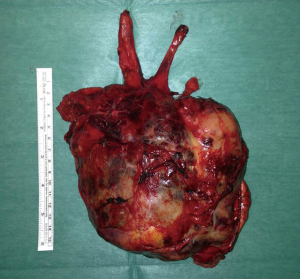

Compared to thymic carcinomas, NETTs were more likely larger in size (thymic carcinoma median tumor size: 6.2 cm; NETT median size: 7.9 cm) thymic carcinomas, on the other side, presented in advanced stage more frequently than NETTs (13,14). Approximately 50% of NETTs were encapsulated, but very often, gross invasion of the surrounding mediastinal structures was observed. Very frequently, NETTs presented with central foci of necrosis or hemorrage, especially in large lesions (Figure 1).

A preoperative histological confirmation should be generally achieved in case of large locally invasive tumors, or in case of functional lesions, as well as in asymptomatic but fast-growing mediastinal lesions. In particular, core biopsy or parasternal mediastinotomy (the so called Chamberlain procedure) were the preferred approaches to obtain a correct histological confirmation. In fact, a differential diagnosis with other mediastinal lesions, such as thymomas, thymic carcinomas or lymphomas was always needed.

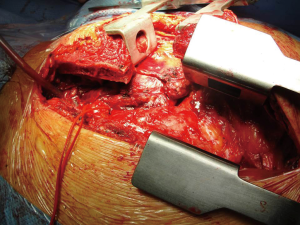

NETT’s patients should be routinely referred and approached in a multidisciplinary setting, as well as in experienced centers (15). Indeed, in case of invasive/advanced NETTs, an aggressive multidisciplinary treatment (induction chemotherapy, followed by surgery and postoperative chemo and/or radiotherapy) was indicated (16-18). Resection of the primary tumor along with the invaded mediastinal structures should be always performed. Median sternotomy was the preferred access to resect a NETT. In case of advanced tumors (with great vessels or lung invasion or pleural deposits), anterior, lateral or posterolateral thoracotomy, alone or in combination with sternotomy may be used. These accesses provided an excellent exposure to all the mediastinum and the pleural space (19,20) (Figure 2). Therefore, limited surgical approaches or minimally-invasive techniques had usually no role in NETTs surgery.

Resectability rate ranged from 28% to 100% (mean: 86%) in the published series. It mainly depended on the single center’s surgical experience (21). Incomplete resections mostly resulted from NETT local invasiveness, with tumoral residuals in great vessels, heart, trachea, aorta or phrenic nerves. As a matter of fact, debulking surgery usually had no role in aggressive neoplasms like NETTs (22).

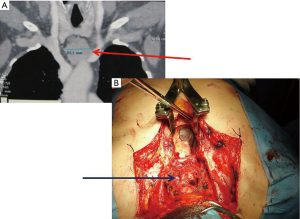

Even in case of complete resection, prognosis was poor, due to the NETTs aggressive behavior along with a high incidence of tumor recurrences after surgery. Like thymomas, NETTs recurrences may classified as local (in the anterior mediastinum), regional (intrathoracic) or distant (outside the chest or in case of intrapulmonary nodules). Recurrent local disease was sometimes surgically approached, if a complete resection was deemed feasible. Few cases have been described in the literature (23-25): we observed 3 relapses (2 local, 1 intrathoracic) in our recent 6 operated NETTs, in which surgery was effective (unpublished data) (Figure 3). Successful aggressive surgical approach (sometimes with the use of cardiopulmonary by-pass) and postoperative RT have been reported to be effective in recurrent NETTs, with significative improvement of survival (26-28). Currently, Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) seemed to be very effective for the systemic treatment of metastatic neuroendocrine tumors, where surgery was not feasible. PRRT is a form of molecular targeted therapy performed by using a small peptide (a somatostatin analog similar to octreotide) coupled with a radionuclide emitting beta radiation. The tumor absorbs both the drug and the radionuclide and the emitted beta particles will kill the neoplastic cells. The most effective radionuclides currently used are 177Lutetium and 90Yttrium.

Finally, since NETTs were the main cause of death in MEN-1 patients, several Authors recommend a prophylactic resection of the thymus at the time of parathyroidectomy, using the same surgical access (13,29-31). This condition reduced the risk of NETTs occurrence during life.

Prognostic factors

Reported intermediate-term survival in NETTs patients was fairly good, especially in case of complete surgical resection. Table 1 showed treatment, overall survival (OS) and cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) of the most recent (since 1990) published NETTs series.

Full table

Patients who underwent surgery, and those who received a complete resection had improved OS, compared with those who did not. Therefore, the possibility to undergo surgery and the completeness of resection were the strongest prognostic factors (7,19,29-30). As for thymomas, NETTs early stage patient survived longer and less frequently developed recurrences, as reported in some clinical series (4,10,32-34).

The study of Filosso et al. (10), based on 205 NETTs cases joining the International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group (ITMIG) and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) retrospective thymic databases, described that tumor histology was not a prognostic indicator for either OS and CIR. Nevertheless, this data was in contrast with other published series, describing fewer patients (4,21,34).

Furthermore, prognosis was also dependent by the presence of associated endocrinopaties. As reported by Wick and Coll (35), patients with NETTs and Cushing’s syndrome or MEN-1 syndrome had a 65% 5-year mortality, compared to 35% mortality for those without paraneoplastic syndromes.

Unlike that in advanced stage thymomas, the role of adjuvant CT/RT in NETTs had not yet been outlined. In several recent published series, a preoperative treatment (usually CT) was advocated to obtain tumor shrinkage with a consequent higher probability for a complete resection (21,33). On the other hand, only Tiffet and Coll (32) showed a better outcome (no recurrence development) for those patients who received RT after a complete NETT surgical resection. On the contrary, Cardillo (21) and Gaur (36) reported a detrimental postoperative RT effect. In addiction, Filosso et al. (10) did not find any statistical advantage in OS for adjuvant CT/RT; furthermore, CIR was not statistically influenced by induction/adjuvant treatments. Anyway, a trend to administer induction CT ± RT and adjuvant CT/RT according to the NETT’s invasiveness, resection status and possible presence of lymphnodal involvement was recently observed. The exact CT/RT role in NETTs should be studied in future randomized clinical trials (37).

Due to the high risk of recurrence or distant metastases development, a close and life-long clinical-radiological follow-up was mandatory for NETTs patients. The Authors suggested that a Thoracic CT scan every 6 months for the first 3 years should be performed; in case of recurrence, thoracic MRI and/or Octreoscan scintigraphy may be indicated to assess the tumor’s resectability.

Final remarks

In summary, NETTs were rare and biologically aggressive mediastinal neoplasms. They were more frequently observed in males and in about 50% of cases are associated with endocrinopaties. NETTs should be always approached in a multidisciplynary setting. As a matter of fact, surgery, even in advanced stages, was the mainstay of treatment: a complete resection through a median sternotomy or a combined approach (sternotomy + thoracotomy) should be always attempted. On the other hand, induction CT (or CT + RT) was usually administered in case of advanced NETT, with the aim to achieve tumor shrinkage, increasing therefore the probability of a R0 resection. Adjuvant RT/CT is offered in case of invasive tumors or when an incomplete resection has been performed. Unfortunately, due to the NETTs rarity, and the lack of randomized clinical trials, no definitive evidence on complementary treatment effectiveness were currently available in the literature. Finally, the long-term outcome was poor, even in case of a complete surgical resection, due to the NETTs high risk of recurrence or distant metastases development. In effect, prognosis was mainly dependent by tumor stage, invasivity, completeness of resection and possible association with endocrinopaties.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Rosai J, Higa E. Mediastinal endocrine neoplasm, of probable thymic origin, related to carcinoid tumor. Clinicopathologic study of 8 cases. Cancer 1972;29:1061-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after "carcinoid": epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3063-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wick MR, Carney JA, Bernatz PE, et al. Primary mediastinal carcinoid tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 1982;6:195-205. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gaur P, Leary C, Yao JC. Thymic neuroendocrine tumors: a SEER database analysis of 160 patients. Ann Surg 2010;251:1117-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klemm KM, Moran CA. Primary neuroendocrine carcinomas of the thymus. Semin Diagn Pathol 1999;16:32-41. [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, et al. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart, Fourth edition. France: International Agency for Research on Cancer 2015;234-42.

- Filosso PL, Guerrera F, Rendina AE, et al. Outcome of surgically resected thymic carcinoma: a multicenter experience. Lung Cancer 2014;83:205-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ruffini E, Detterbeck F, Van Raemdonck D, et al. European Society of Thoracic Surgeons Thymic Working Group. Thymic carcinoma: a cohort study of patients from the European society of thoracic surgeons database. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:541-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dusmet ME, McKneally MF. Pulmonary and thymic carcinoid tumors. World J Surg 1996;20:189-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filosso PL, Yao X, Ahmad U, et al. European Society of Thoracic Surgeons Thymic Group Steering Committee. Outcome of primary neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus: a joint analysis of the International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons databases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2015;149:103-9.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Phan AT, Oberg K, Choi J, et al. North American Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (NANETS): NANETS consensus guideline for the diagnosis and management of neuroendocrine tumors: well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors of the thorax (includes lung and thymus). Pancreas 2010;39:784-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mizuno T, Masaoka A, Hashimoto T, et al. Coexisting thymic carcinoid tumor and thymoma. Ann Thorac Surg 1990;50:650-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teh BT. Thymic carcinoids in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. J Intern Med 1998;243:501-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filosso PL, Yao X, Ruffini E, et al. Comparison of outcomes between neuroendocrine thymic tumours and other subtypes of thymic carcinomas: a joint analysis of the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the International Thymic Malignancy Interest Group. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2016;50:766-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lausi PO, Refai M, Filosso PL, et al. Thymic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Thorac Surg Clin 2014;24:327-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wick MR, Rosai J. Neuroendocrine neoplasms of the mediastinum. Semin Diagn Pathol 1991;8:35-51. [PubMed]

- Filosso PL, Actis Dato GM, Ruffini E, et al. Multisciplinary treatment of advanced thymic neuroendocrine carcinoma (carcinoid): report of a successful case and review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;127:1215-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Girard N, Ruffini E, Marx A, et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Thymic epithelial tumours: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2015;26 Suppl 5:v40-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Rizk NP, Travis WD, et al. Feasibility of multimodality therapy including extended resections in stage IVA thymoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;134:1477-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Riely GJ, Rosenzweig KE, et al. Multimodality therapy for locally advanced thymomas: state of the art or investigational therapy? Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:365-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cardillo G, Treggiari S, Paul MA. Primary neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus: a clinico-pathologic and prognostic study in 19 patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:814-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Girard N, Mornex F, Van Houtte P, et al. Thymoma: a focus on current therapeutic management. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:119-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nawata S, Kaneda Y, Hirayama T, et al. Recurrent thymic carcinoid tumor--report of a case. Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1991;39:962-6. [PubMed]

- Inoue M, Sato S, Sakagoshi N, et al. Surgical treatment of recurrent thymic carcinoid-a case report. Nihon Kyobu Geka Gakkai Zasshi 1994;42:1188-92. [PubMed]

- Tsuchida M, Yamato Y, Hashimoto T, et al. Recurrent thymic carcinoid tumor in the pleural cavity. 2 cases of long-term survivors. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001;49:666-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Economopoulos GC, Lewis JW Jr, Lee MW, et al. Carcinoid tumors of the thymus. Ann Thorac Surg 1990;50:58-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakuragi T, Rikitake K, Nastuaki M, et al. Complete resection of recurrent thymic carcinoid using cardiopulmonary bypass. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2002;21:152-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fukai I, Masaoka A, Fujii Y, et al. Thymic neuroendocrine tumor (thymic carcinoid): a clinicopathologic study in 15 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67:208-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeiger MA, Swartz SE, MacGillivray DC, et al. Thymic carcinoid in association with MEN syndromes. Am Surg 1992;58:430-4. [PubMed]

- Trump D, Farren B, Wooding C, et al. Clinical studies of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1). QJM 1996;89:653-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Teh BT, Zedenius J, Kytölä S, et al. Thymic carcinoids in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1. Ann Surg 1998;228:99-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tiffet O, Nicholson AG, Ladas G, et al. A clinicopathologic study of 12 neuroendocrine tumors arising in the thymus. Chest 2003;124:141-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Montpréville VT, Macchiarini P, Dulmet E. Thymic neuroendocrine carcinoma (carcinoid): a clinicopathologic study of fourteen cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996;111:134-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gal AA, Kornstein MJ, Cohen C, et al. Neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus: a clinicopathological and prognostic study. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:1179-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wick MR, Scott RE, Li CY, et al. Carcinoid tumor of the thymus: a clinicopathologic report of seven cases with a review of the literature. Mayo Clin Proc 1980;55:246-54. [PubMed]

- Gaur P, Leary C, Yao JC. Thymic neuroendocrine tumors: a SEER database analysis of 160 patients. Ann Surg 2010;251:1117-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guerrera F, Renaud S, Tabbò F, et al. How to design a randomized clinical trial: tips and tricks for conduct a successful study in thoracic disease domain. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:2692-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]