Prognostic prediction of clinical stage IA lung cancer presenting as a pure solid nodule

Introduction

Lung cancer has many histological subtypes (1). One of them, lung adenocarcinoma, can often be accurately predicted before biopsy or surgery due to its classic appearance as a ground glass opacity (GGO) on chest computed tomography (CT) (2). In GGO lung cancer, the size of the entire tumor or the solid portion can affect the prognosis (3). If the GGO nodule is presenting as pure GGO or has a solid portion less than 5 mm, it is highly likely to be an adenocarcinoma in situ or a minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and a good prognosis is expected following surgical resection (4,5). Conversely, lung cancer presenting as a pure solid nodule (pure solid lung cancer) generally has a worse prognosis than GGO lung cancer. However, the prognosis of pure solid nodule lung cancer is not always poor. In fact, even among pure solid nodule lung cancer, there are some tumors that carry a good prognosis after surgical resection. GGO lung cancer is predominantly adenocarcinoma, although pure solid nodules are a radiologic feature in various histologic types of lung cancer ranging from adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma to small cell carcinoma. Given this, the characteristics and prognosis of pure solid lung cancers are heterogeneous.

The standard treatment of early stage lung cancer is anatomical lobectomy (6). However, in the case of stage IA GGO lung cancer, it is well known that sublobar resection is also an effective treatment option (7,8). GGO lung cancer is known to have a low risk of lymph node metastasis, so lymph node dissection may not be necessary for clinical stage IA GGO lung cancer (9-13). There has not been a comprehensive analysis of appropriate treatment regimens in early stage pure solid lung cancer. Generally, only lobectomy or greater with systematic lymph node dissection is considered to be an appropriate treatment, even in stage IA. Therefore, the development of a method to determine the prognosis in pure solid lung cancers may be helpful in determining the most appropriate treatment regimen.

The purpose of this study is to identify the predictive factors determining prognosis after surgical treatment of clinical stage IA pure solid lung cancer. We believe that by predicting the prognosis of pure solid lung cancer before surgery and by differentiating tumors according to prognosis, we can better establish appropriate treatment plans.

Methods

Patients

Between January, 2006 and December, 2016, 1,571 consecutive patients were diagnosed with and surgically treated for lung cancer at Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital at the Catholic University of Korea. Of those patients, 918 patients were diagnosed as clinical T1N0M0 (stage IA) and there were 344 patients with a pure solid nodule tumor identified on chest CT. None of the patients included in the study had an incomplete resection or received preoperative chemo- or radiotherapy. Sixteen patients were excluded from the study because they had synchronous lung cancer or multiple nodules. Our standard procedure for radiologic solid lung cancer is anatomical lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection. Sublobar resection (wedge resection or segmentectomy) was performed in high-risk patients with reduced pulmonary function or comorbid conditions, such as cardiopulmonary disease and advanced age. When we performed sublobar resection, lymph node dissection or sampling was done only in enlarged lymph nodes. A total of 328 consecutive patients undergoing curative resection of clinical stage IA pure solid lung cancer were reviewed retrospectively. Predictive factors for recurrence and cancer-related death of those patients were analyzed.

The occurrence of postoperative upstaging was also analyzed. Of 328 patients, 217 patients who underwent surgical procedures including lobectomy and mediastinal lymph node dissection of more than three mediastinal lymph node stations were selected. The technique used for lymph node dissection was en-bloc resection of the lymph nodes, including the adjacent fatty tissue. The incidence of upstaging was evaluated and nodal upstaging was analyzed in detail. Patients were classified into 2 groups: those diagnosed with preoperative clinical N0 (cN0) tumors and postoperative pathologic N0 (pN0) tumors (pN0 group), and those diagnosed with preoperative cN0 tumors and pathologic N1 or pathologic N2 tumors postoperatively (nodal upstaging group). Clinicopathological characteristics of tumors in the two groups were compared. Risk factors for upstaging were also analyzed.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital at the Catholic University of Korea (ID: KC17RESI0719).

Preoperative radiologic evaluation and clinical staging

Primary lesions were evaluated using thin-section CT images. All chest CT scans were obtained during a deep inspiration and were retrospectively examined for pulmonary nodules. On a CT scan, GGO is defined as increased hazy opacities in the lung parenchyma with preservation of the bronchial structures and vascular margins (14). The diameter of the tumor (T) was defined as the largest diameter of the lesion in the lung window setting. The diameter of consolidation (C) in the lung window setting was also measured; consolidation was defined as an area of increased opacification that completely obscured the underlying bronchial structures and vascular markings. We calculated the C/T ratio as a variable. A pure solid nodule is defined as having a C/T ratio of 1.0.

TNM staging was based on the eighth edition of the TNM classification proposed by the International Association of Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC) (15). Clinical T staging was determined using only nodule size on CT image. Pleural retraction or tags were not interpreted as visceral pleural invasion or parietal pleural invasion. Lymph node staging was performed using contrast-enhanced chest CT and F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET) scanning. Lymph nodes were considered malignant if their short axis diameter was greater than 10 mm on a CT scan and if their FDG uptake was greater than that of the surrounding mediastinal structures. However, an enlarged lymph node or a lymph node with high FDG uptake was considered benign if the lymph node contained benign calcifications or if unenhanced CT images showed high attenuation with a distinct margin. In patients with general symmetric and equivocal FDG uptake in the mediastinal lymph nodes on a PET/CT scan, it was interpreted as reactive inflammatory changes (16,17). In patients diagnosed with cN0 tumors using chest CT and PET/CT scanning, surgery was performed without preoperative invasive lymph node staging if complete resection was considered possible.

Follow-up evaluations

All patients were followed from the day of surgery. They were examined physically and by chest radiography every 3 months and by chest CT covering cervical to abdominal lesions every 6 months for the first 2 years. Thereafter, they were examined physically and by low-dose chest CT every 6 months up to 5 years. After 5 years, they were examined physically and by low-dose chest CT annually.

Statistical analysis

Clinicopathological characteristics of all patients were described. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to analyze data from the interval between surgical resection and the time of the final follow-up visit, as well as to calculate recurrence-free survival and disease-specific survival using confirmed recurrences and cancer-related deaths. In a multivariate analysis, the Cox proportional hazards model was used to determine the risk of recurrence and cancer-related death for all patients. All variables with a P of <0.1 in the univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate analysis. A P of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Clinicopathological characteristics of the pN0 tumors were compared with those in the nodal upstaging group. The Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for continuous variables and the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was applied for categorical variables. A multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze factors influencing nodal upstaging after surgery. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

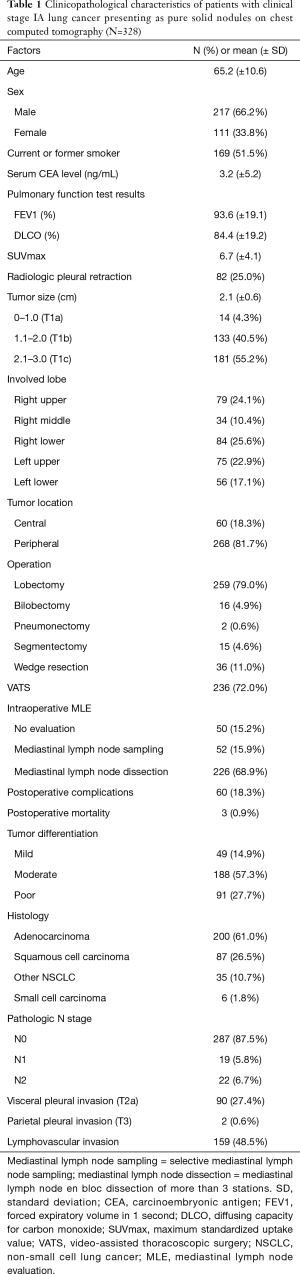

The clinicopathological characteristics of all 328 patients are described in Table 1. The mean age was 65.2 (±10.6) years and the number of males (66.2%) was greater than females. Clinical T1a, T1b, and T1c staging were described in 14 (4.3%), 133 (40.5%), and 181 (55.2%) patients, respectively.

Full table

Survival analysis and predictive factors for recurrence and cancer-related death

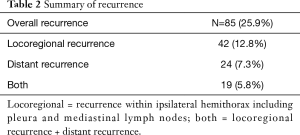

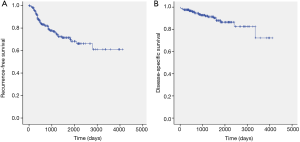

The median follow-up time for all patients was 36.5 months (range, 0.4–135.4 months), with recurrence identified in 85 patients (Table 2). Among those patients, locoregional recurrence occurred in 42 (49.4%). The 5-year recurrence-free survival rate and disease-specific survival rate of the patients with stage IA pure solid lung cancer was 70.0% and 86.5%, respectively (Figure 1).

Full table

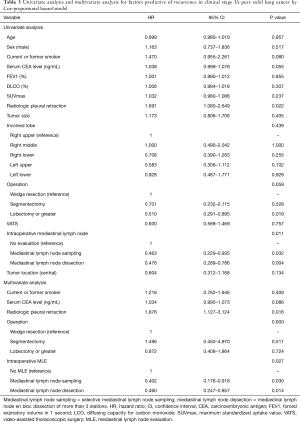

The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses by the Cox proportional hazards model performed to identify predictive factors impacting recurrence are shown in Table 3. Specific variables identified as significant (P<0.1) by univariate analysis include history of smoking, serum CEA level, radiologic pleural retraction, surgical procedures, and the performance of intraoperative mediastinal lymph node evaluation (MLE). These variables were entered into the multivariate model. The presence of radiologic pleural retraction [hazard ratio (HR) =1.876, P=0.016] and the performance of intraoperative MLE (selective mediastinal lymph node sampling, HR =0.402, P=0.030; mediastinal lymph node dissection more than 3 stations, HR =0.460, P=0.014) were significant related factors predicting recurrence.

Full table

The univariate and multivariate analyses were also conducted to identify predictive factors impacting cancer-related death. Specific variables identified as significant (P<0.1) by univariate analysis include age, sex, smoking history, surgical procedures, VATS, and intraoperative MLE; these variables were entered into the multivariate model. Only mediastinal lymph node dissection more than 3 stations was a significantly good prognostic factor [HR =0.337, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.141–0.809, P=0.015].

Upstaging after surgery and associated risk factors

A total of 217 patients who underwent more than lobectomy with mediastinal lymph node dissection were evaluated. Of those patients, upstaging of the N stage occurred in 36 patients (16.6%; 15 N1 patients and 21 N2 patients).

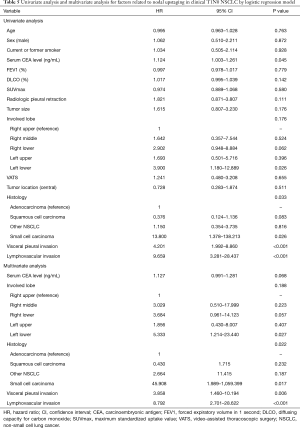

We performed an analysis of lymph node upstaging. A comparison of the clinicopathological characteristics in the pN0 group and the nodal upstaging group is shown in Table 4. The distribution of histologic types (P=0.009) and the incidence of pleural invasion and lymphovascular invasion varied (P<0.001 and P<0.001). Logistic regression analysis was used to determine the risk factors for lymph node upstaging (Table 5). In a univariate analysis, serum CEA level, lobe involved, histologic type, visceral pleural invasion, and lymphovascular invasion had P values of <0.1. Small cell carcinoma, visceral pleural invasion and lymphovascular invasion were confirmed to be significant risk factors for nodal upstaging after surgery in a multivariate analysis (HR =45.908, P=0.017; HR =3.858, P=0.006; HR =8.792, P<0.001, respectively).

Full table

Full table

Discussion

The most powerful predictor of lung cancer prognosis is the TNM stage (18). The new TNM staging system of the 8th edition more clearly illustrates the differences in survival according to the stage of cancer (15). In addition to stage, histopathologic characteristics also serve as a factor in predicting lung cancer prognosis (1,19). Particularly in stage I lung cancer, histologic types and many other factors can alter prognoses (20,21). Therefore, there is a continuing effort to identify prognostic factors in addition to the TNM staging system and to better elucidate the prognosis even within the same stage. GGO lung cancer is known to have a very good prognosis, while pure solid nodule lung cancer has a relatively poorer prognosis (22,23). In this study, we evaluated the factors that could predict recurrence and cancer-related death in order to better determine prognosis among pure solid lung cancer. We also investigated the factors predictive of nodal upstaging in patients with clinical N0 pure solid lung cancer, since lymph node metastasis is a very important prognostic factor. In our study, factors that accurately predicted the prognosis of pure solid lung cancer included the presence of radiologic pleural retraction on the preoperative CT and lymph node dissection during surgery. Radiologic pleural retraction is associated with upstaging of the T stage because it is a factor that indicates the possibility of visceral pleural invasion. Mediastinal lymph node dissection is performed during surgery as an effort to accurately determine N staging. There were no preoperative factors that accurately predicted postoperative nodal upstaging. Therefore, only the efforts for accurate staging before surgery and during surgery will affect the prognosis of pure solid lung cancer.

Nodal upstaging is very important for determining prognosis. Pathologic N0 lung cancer generally does not require adjuvant postoperative treatment. However, adjuvant treatment is recommended for pathologic N1 or N2 disease even if the tumor is completely resected (24-26). Even despite adjuvant treatment, the prognosis of N1 and N2 disease is poorer than that of pathologic N0 stage disease. Therefore, nodal upstaging is important in predicting the prognosis (17). In GGO lung cancer, nodal upstaging rarely occurs (9,10,13). Conversely, nodal upstaging is relatively common in pure solid lung cancer (27). In this study, nodal upstaging occurred in 16.6% of patients. Therefore, we searched for factors to predict the occurrence of nodal upstaging. Unfortunately, none of the preoperative and intraoperative factors examined predicted nodal upstaging. Only histological features such as visceral pleural or lymphovascular invasion and small cell carcinoma were risk factors for nodal upstaging. In summary, preoperative clinical factors did not predict nodal upstaging; only surgical or histologic examination could predict nodal upstaging. Therefore, pure solid lung cancer requires adequate histologic examination and systematic lymph node dissection during surgery for accurate staging even in clinical N0 stage disease.

Conventionally, sublobar resection has not been considered a suitable treatment for pure solid stage IA lung cancer (6). Many surgeons feel that lobectomy or greater with mediastinal lymph node dissection is suitable for pure solid lung cancer (28). Conversely, many surgeons believe that sublobar resection is an adequate surgical treatment for GGO lung cancer. There are many studies showing a favorable prognosis after sublobar resection in GGO lung cancer (7,29,30). Recently, there have been many efforts to apply sublobar resection for pure solid lung tumors. Two randomized controlled trials (JCOG 0802, CALGB 140503) evaluating sublobar resection for the treatment of solid lung cancer are ongoing (31,32). In this study, sublobar resection was not a risk factor for recurrence or cancer-related death in a multivariate analysis. Only the performance of lymph node dissection and the presence of pleural retraction were significant risk factors. It can be surmised that accurate staging is the most important risk factor and that sublobar resection may be possible given accurate staging. However, given that the purpose of this study is not to demonstrate the efficacy of sublobar resection for pure solid lung cancer, further research endeavors should be undertaken to determine the safety and efficacy of this approach.

This study had a number of limitations. First, this was a retrospective review. Second, we obtained data from a single institution and there was an insufficient sample size to generalize our results. However, this study examined data from surgical patients under a relatively standardized protocol at our single center, a tertiary hospital in Korea. Furthermore, a more detailed analysis was possible due to the detailed records available from the electronic medical record. Finally, the follow-up period was relatively short. Still, most recurrences of NSCLC are known to occur within a two-year period postoperatively (33) and early recurrence has been shown to accurately reflect the extended prognosis (34).We believe that our data can be used as a baseline to support future investigations. A larger scale study should be performed to validate our results.

In conclusion, there was no definite predictor of the postoperative prognosis of clinical stage IA pure solid nodule lung cancer. Intraoperative MLE was the only significant prognostic factor related to recurrence and cancer-related mortality. In addition, nodal upstaging after surgery was difficult to predict preoperatively. Therefore, even for patients with clinical stage IA lesions, an accurate staging process and histologic evaluation are required prior to treatment. Adequate intraoperative systematic lymph node dissection is essential for patients with clinical stage IA pure solid lung cancer.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital at the Catholic University of Korea (ID: KC17RESI0719).

References

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG, et al. The 2015 World Health Organization Classification of Lung Tumors: Impact of Genetic, Clinical and Radiologic Advances Since the 2004 Classification. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:1243-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duann CW, Hung JJ, Hsu PK, et al. Surgical outcomes in lung cancer presenting as ground-glass opacities of 3 cm or less: a review of 5 years’ experience. J Chin Med Assoc 2013;76:693-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim HJ, Ahn S, Lee KS, et al. Persistent pure ground-glass opacity lung nodules >/= 10 mm in diameter at CT scan: histopathologic comparisons and prognostic implications. Chest 2013;144:1291-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Asamura H, Bankier AA, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Coding T Categories for Subsolid Nodules and Assessment of Tumor Size in Part-Solid Tumors in the Forthcoming Eighth Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1204-23.

- Wilshire CL, Louie BE, Manning KA, et al. Radiologic Evaluation of Small Lepidic Adenocarcinomas to Guide Decision Making in Surgical Resection. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:979-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:615-22; discussion 22-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cho JH, Choi YS, Kim J, et al. Long-term outcomes of wedge resection for pulmonary ground-glass opacity nodules. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;99:218-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moon Y, Lee KY, Moon SW, et al. Sublobar Resection Margin Width Does Not Affect Recurrence of Clinical N0 Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Presenting as GGO-Predominant Nodule of 3 cm or Less. World J Surg 2017;41:472-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haruki T, Aokage K, Miyoshi T, et al. Mediastinal nodal involvement in patients with clinical stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: possibility of rational lymph node dissection. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:930-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moon Y, Sung SW, Namkoong M, et al. The effectiveness of mediastinal lymph node evaluation in a patient with ground glass opacity tumor. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:2617-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moon Y, Park JK, Lee KY, et al. Consolidation/Tumor Ratio on Chest Computed Tomography as Predictor of Postoperative Nodal Upstaging in Clinical T1N0 Lung Cancer. World J Surg 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsutani Y, Miyata Y, Yamanaka T, et al. Solid tumors versus mixed tumors with a ground-glass opacity component in patients with clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma: prognostic comparison using high-resolution computed tomography findings. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;146:17-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ye B, Cheng M, Li W, et al. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:217-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hansell DM, Bankier AA, MacMahon H, et al. Fleischner Society: glossary of terms for thoracic imaging. Radiology 2008;246:697-722. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldstraw P, Chansky K, Crowley J, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Proposals for Revision of the TNM Stage Groupings in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:39-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu P, Sun Y, Sun Y, et al. The role of (18)F-FDG PET/CT for evaluation of metastatic mediastinal lymph nodes in patients with lung squamous-cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer 2014;85:53-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moon Y, Kim KS, Lee KY, et al. Clinicopathologic Factors Associated With Occult Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients With Clinically Diagnosed N0 Lung Adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:1928-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang L, Wang S, Zhou Y, et al. Evaluation of the 7(th) and 8(th) editions of the AJCC/UICC TNM staging systems for lung cancer in a large North American cohort. Oncotarget 2017;8:66784-95. [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:244-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sica G, Yoshizawa A, Sima CS, et al. A grading system of lung adenocarcinomas based on histologic pattern is predictive of disease recurrence in stage I tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:1155-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuo SW, Chen JS, Huang PM, et al. Prognostic significance of histologic differentiation, carcinoembryonic antigen value, and lymphovascular invasion in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:1200-7.e3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hattori A, Matsunaga T, Takamochi K, et al. Neither Maximum Tumor Size nor Solid Component Size Is Prognostic in Part-Solid Lung Cancer: Impact of Tumor Size Should Be Applied Exclusively to Solid Lung Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:407-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hattori A, Matsunaga T, Takamochi K, et al. Importance of Ground Glass Opacity Component in Clinical Stage IA Radiologic Invasive Lung Cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:313-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Douillard JY, Rosell R, De Lena M, et al. Adjuvant vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus observation in patients with completely resected stage IB-IIIA non-small-cell lung cancer (Adjuvant Navelbine International Trialist Association [ANITA]): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2006;7:719-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Douillard JY, Tribodet H, Aubert D, et al. Adjuvant cisplatin and vinorelbine for completely resected non-small cell lung cancer: subgroup analysis of the Lung Adjuvant Cisplatin Evaluation. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:220-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry MF, Coleman BK, Curtis LH, et al. Benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy after resection of stage II (T1-2N1M0) non-small cell lung cancer in elderly patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2015;22:642-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hattori A, Suzuki K, Matsunaga T, et al. Is limited resection appropriate for radiologically "solid" tumors in small lung cancers? Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:212-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khullar OV, Liu Y, Gillespie T, et al. Survival After Sublobar Resection versus Lobectomy for Clinical Stage IA Lung Cancer: An Analysis from the National Cancer Data Base. J Thorac Oncol 2015;10:1625-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sim HJ, Choi SH, Chae EJ, et al. Surgical management of pulmonary adenocarcinoma presenting as a pure ground-glass nodule. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;46:632-6; discussion 636. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshida J, Nagai K, Yokose T, et al. Limited resection trial for pulmonary ground-glass opacity nodules: fifty-case experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:991-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamura K, Saji H, Nakajima R, et al. A phase III randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for small-sized peripheral non-small cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40:271-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blasberg JD, Pass HI, Donington JS. Sublobar resection: a movement from the Lung Cancer Study Group. J Thorac Oncol 2010;5:1583-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tremblay L, Deslauriers J. What is the most practical, optimal, and cost effective method for performing follow-up after lung cancer surgery, and by whom should it be done? Thorac Surg Clin 2013;23:429-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kiankhooy A, Taylor MD, LaPar DJ, et al. Predictors of early recurrence for node-negative t1 to t2b non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2014;98:1175-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]