Is “lung repair centre” a possible answer to organ shortage?—transplantation of left and right lung at two different centres after ex vivo lung perfusion evaluation and repair: case report

Introduction

Ex vivo lung perfusion (EVLP) has become a cornerstone in clinical practice of lung transplantation centers as a platform to assess the function of questionable organs, as well as a tool to recondition lungs from marginal donors (1).

Actually, EVLP opens the door to new organizational assets in the process of donation and transplantation. It is widely debated whether to promote the development of EVLP programs in every transplant center, or to identify specialized centers that carry out the process on behalf and in favor of other transplant teams (2). The latter possibility would offer the opportunity of creating a working platform with a dedicated team dealing with a greater number of procedures, enabling cost containment and possibly more favorable outcomes.

The Toronto group previously proved the feasibility of such an ‘EVLP Center’ concept in a case of urgent transplantation (3) and the Perfusix trial is ongoing in order to extend this approach to the daily clinical practice (4). Hereafter we report of a successful transplantation of two recipients after lung procurement, EVLP reconditioning and subsequent lung offer to a distant lung transplantation center in an elective setting, with a long favorable follow-up.

Case presentation

In May 2014 the local organ procurement organization (Nord Italian Transplant program, NITp) proposed the lungs of a 53-year-old male donor, non-smoker, who died from cerebral hemorrhage. The chest X-ray showed hilar reinforcement and basal dysventilation. The bronchoscopic examination revealed a moderate quantity of secretions; PaO2 ratio at the time of offer was 264. After recruitment maneuvers PaO2/FiO2 ratio was 294. The donor was ventilated with protective setting: TV 7 mL/kg, PEEP 8 mmHg. The time of intubation was 36 hours. Bronchoscopy revealed moderate, central, non-purulent secretions. At visual inspection lungs were wet and moderate bilateral basal atelectasis were present at visual inspection, reopened after recruitment maneuvers. Selective blood gases were not performed. Oto score was 10.

The transplant team of Milan decided to accept the graft for a left single transplantation, under the condition of EVLP evaluation, while the Padua transplant center agreed to accept the right lung if suitable for transplantation.

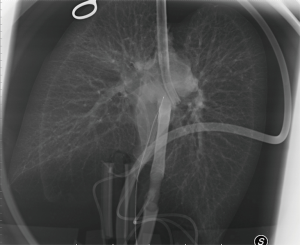

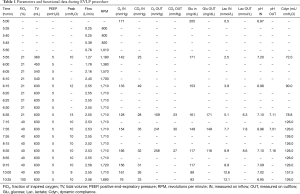

After usual procurement at the donor’s hospital, the bi-pulmonary block was transferred to Milan and EVLP was run with a low-flow, open atrium and low haematocrit technique, as previously described (Figure 1) (5). The parameters and functional data during EVLP procedure are shown in Table 1. At the end of the procedure the two lungs were evaluated separately and both judged suitable for transplantation: oxygenation assessed on perfusate output from left and right lungs was 553 and 496 mmHg, respectively, without signs of function deterioration over time, clear bronchoscopy and chest X-ray (Figure 2).

Full table

Throughout lung procurement and EVLP, donor’s files and lung function data were shared between the two teams that both agreed about suitability for transplantation.

After cooling, the bi-pulmonary block was separated on the back-table, and the lungs were stored on ice. The left graft was transplanted in Milan to a 66-year-old male subject with pulmonary fibrosis (LAS: 35); the right lung was transferred on ice to Padua (250 km distant from Milan), and transplanted to a subject with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (LAS: 50). The ischemic times from cross-clamping to revascularization for left and right lung were 18 and 15 hours, respectively. Neither of the recipients suffered from primary graft dysfunction (PGD) in the first 72 hours.

The subject transplanted in Milan was extubated in the first post-operative day (POD). The subsequent course was complicated with a Klebsiella pneumonia carbapenemase (KPC) respiratory infection and related multi-organ failure (MOF). After a slow recovery, he was discharged on POD 52 in good condition with a FEV1 of 55%. Six, nine and twelve-month surveillance trans-bronchial biopsy (TBB) showed a minimum degree of acute rejection, with no evidence of chronic rejection and with no neutrophilia. At one-year, the bronchoalveolar lavage was negative for KPC, but a stenosis in the main bronchus beyond the anastomosis was noted; such stenosis has been successfully treated with pneumatic dilations and a resorbable stent. Twenty-fourth months after surgery, pulmonary function tests (PFTs) showed FEV1: 80% and FVC: 76%; the best FEV1 was 90%. The subject is alive thirty months after the transplantation without signs of chronic rejection.

The patient who was transplanted in Padua, had an uneventful post-operative period and was discharged 27 days after surgery. Also this patient is alive thirty months after the transplantation without signs of chronic rejection: his last PFTs showed FEV1: 62% and FVC: 92%.

Discussion

Wigfield previously reported a case of a marginal lung transferred from the donor’s hospital to the ‘organ repair center’ in Toronto, and then back to the recipient’s hospital after EVLP reconditioning (3). The mentioned case was carried on in an urgent condition; on the contrary, we report a lung transplantation after assessment of the graft with EVLP and transplantation in a remote center in an elective setting.

The continuous sharing of information, timing of the procedure and functional data between the two centers have been the key of the success. Certainly, the expertise of the Padua center, which is confident with the Organ Care System (OCS) and ex situ lung perfusion techniques, played a role in their decision to accept an organ assessed from another center (6). However, the decision of both groups to closely collaborate for the benefit of their respective recipients was fundamental for the good outcome.

Conclusions

In our view, this single experience opens the door to a new allocation model with great potential against organ shortage and with possible benefits on cost containment. In fact, our case is proof of the concept that a ‘lung repair center’ is feasible and effective, as shown by the long-term favorable outcome of both recipients. Such ‘hub and spoke model’, although promising, need to be fully explored before concluding on its validity.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by Ethics committee of Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico Milano. Mortality risk factors in patients waiting and submitted to lung transplant. Ref. n° 181 (24/01/2017). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this manuscript and any accompanying images.

References

- Van Raemdonck D, Neyrinck A, Cypel M, et al. Ex-vivo lung perfusion. Transpl Int. 2015;28:643-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whitson BA, Black SM. Organ assessment and repair centers: The future of transplantation is near. World J Transplant 2014;4:40-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wigfield CH, Cypel M, Yeung J, et al. Successful emergent lung transplantation after remote ex vivo perfusion optimization and transportation of donor lungs. Am J Transplant 2012;12:2838-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Extending Preservation and Assessment Time of Donor Lungs Using the Toronto EVLP System™ at a Dedicated EVLP Facility. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02234128

- Valenza F, Rosso L, Coppola S, et al. Ex vivo lung perfusion to improve donor lung function and increase the number of organs available for transplantation. Transpl Int 2014;27:553-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schiavon M, Di Gregorio G, Marulli G, et al. Feasibility and Utility of Chest-X ray on Portable Normothermic Perfusion System. Transplantation 2016;100:e48-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]