Patient selection for VV ECMO: have we found the crystal ball?

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) has emerged as a promising intervention for supporting patients with severe cardiorespiratory failure refractory to conventional management (1,2). As the technology is becoming safer, familiar and easier to use, the application of ECMO is likely to increase. However, ECMO still is invasive with significant potential for complications, resource intense and may present economic challenges to the health system (3). Risk prediction models were developed to help the clinicians identify the patients who would benefit from ECMO. However, these models should not be cumbersome, be easy to calculate and have good calibration and discriminatory power.

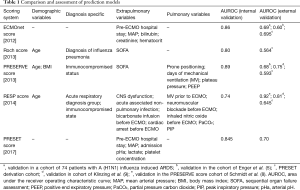

Several ECMO prediction models have been published over the last 7 years (4-8) to help select patients for veno-venous (VV) ECMO and are summarised in Table 1. Hilder et al. recently evaluated four risk prediction models in patients undergoing VV ECMO for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Their analysis included the ECMOnet score, Predicting death for severe ARDS on VV ECMO (PRESERVE) score, Roch et al.’s score and respiratory ECMO survival prediction (RESP) score. The authors also proposed a novel prediction model called the prediction of survival on ECMO therapy score (PRESET) score based on pre-ECMO clinical variables (10). This is an interesting study as it has externally validated RESP score and ECMOnet score. RESP score and ECMOnet score differentiated survivors from non-survivors. RESP score was developed in a largest cohort of 2,355 patients from 280 centres from data extracted from ELSO registry and involves use of 12 variables. On the other hand, ECMOnet score was developed in a patient cohort of only influenza A patients. Age was a common factor in all prediction models except ECMO Net score and the PRESET score.

Full table

PRESET score was developed in a patient cohort of 108 ARDS patients in a German intensive care unit and has only five extrapulmonary variables, i.e., mean arterial pressure, lactate concentration, arterial pH, platelet concentration and hospital stay pre ECMO. It was internally validated in the same centre prospectively. External validation was performed in another German Intensive care unit prospectively which revealed excellent discrimination. PRESET score is relatively easy to calculate and most of the data are routinely available. It is interesting that respiratory variables did not predict survival in this scoring system. It is plausible given that patients receiving ECMO for ARDS invariably have severe pulmonary dysfunction and survival may be determined by the extent of extra pulmonary organ involvement. It is very uncommon for a patient with ARDS to die from of hypoxia alone. As there is no neurological parameter involved in the PRESET score also removes the ambiguity of GCS calculation, which can cause confusion in calculation of score.

Prediction models in ECMO are important as they create a common language to describe the severity of illness and for comparison of risk adjusted outcomes between centres for quality assurance. They will also promote a responsible use of a resource intensive technology in situations where use of ECMO does not realistically increase the chances of survival. Careful patient selection is important, to justify resource utilization and minimise economic burden on health system. They may help clinicians more objectively explain to families why initiating ECMO may not be in the best interest of their loved ones.

As the field of ECMO evolves and its scope widens, it is expected that many peripheral centres may initiate ECMO prior to referral to a higher volume ECMO centre. These are usually patients in whom the risks of transfer on conventional therapies outweigh the risks of ECMO initiation by a less experienced centre. Research suggests higher ECMO hospital volume and lower ECMO mortality in adults in a case mixed adjusted analysis. Risk prediction models can also help in benchmarking intensive care units. There has to be a rigorous process of evaluation and assessment of risk adjusted mortality among the centres providing ECMO. Quality indicators on ECMO will have to be defined to improve and standardise practices. Geographic location and heterogeneous patient population may affect the discriminatory power of the prediction models and will need consideration.

Patients who are supported with ECMO early with predominant single organ failure will have better survival rates than patients with multi organ dysfunction. However, too early an initiation may expose the patient to unnecessary ECMO related complications, whereas late cannulation, when multi-organ failure is already established, may worsen the prognosis. While these prediction models provide direction as to when it is too late to commence ECMO, the question when it is too early remains to be answered. If the technology is not applied appropriately in timely fashion it may falsely overestimate the futility or the benefits.

It should be noted that severity scoring systems do not identify the group of patients in whom death is due to non-recovery from underlying injury process and due to lack of any other bridging options. Long term quality of life in survivors is also an important consideration and ECMO should not become a means to create more disabled survivors of intensive care. Clearly, it is challenging for pre ECMO risk prediction models to predict long term QOL. Apart from premorbid health status and illness severity, long term QOL post ECMO depends largely on quality of care provided while on ECMO.

Equally, centre experience may play a significant role in surviving patients with greater risk. The scoring systems may not truly adjust for centre experience and volume. ECMO is a complex intervention delivered over days to weeks in very unwell patients and the propensity for iatrogenic harm is high. Less experienced centres may delay initiation of ECMO for the fear of iatrogenic harm and may use ECMO as a salvage option. There is a significant variability in ECMO outcomes between centres globally. The ELSO registry summary although provides a pooled estimate of VV ECMO survival based on data from all reporting centres, the reports do not reflect the variability of outcome between centres. Hopefully, in future databases are able to provide risk adjusted outcomes and benchmarking based on prediction models. The Extracorporeal Life Support Organisation and the international research collaborations such as the international ECMO Network (ECMOnet, http://www.internationalecmonetwork.org/) will play an important role in ensuring quality while best practices of ECMO are still being defined.

In summary, in the absence of absolute evidence for the use of ECMO, the scoring systems may be a useful guide to decision making. Sufficient body of literature is now available to assist clinicians in predicting the risk: benefits of ECMO in an individual patient. Clinicians should utilise these scoring systems so that patient selection for ECMO occurs in a relatively objective manner. Holistic evaluation of the patient with consideration to presenting disease pathology and premorbid status should still remain key considerations in decision making.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Shekar K, Mullany DV, Thomson B, et al. Extracorporeal life support devices and strategies for management of acute cardiorespiratory failure in adult patients: a comprehensive review. Crit Care 2014;18:219. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shekar K, Gregory SD, Fraser JF. Mechanical circulatory support in the new era: an overview. Crit Care 2016;20:66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shekar K, Brodie D, Fraser J, et al. Appraising extracorporeal life support - current and future roles in adult intensive care. Crit Care Resusc 2017;19:5-7. [PubMed]

- Roch A, Hraiech S, Masson E, et al. Outcome of acute respiratory distress syndrome patients treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and brought to a referral center. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:74-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Enger T, Philipp A, Videm V, et al. Prediction of mortality in adult patients with severe acute lung failure receiving veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a prospective observational study. Crit Care 2014;18:R67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pappalardo F, Pieri M, Greco T, et al. Predicting mortality risk in patients undergoing venovenous ECMO for ARDS due to influenza A (H1N1) pneumonia: the ECMOnet score. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:275-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt M, Bailey M, Sheldrake J, et al. Predicting survival after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory failure. The Respiratory Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Survival Prediction (RESP) score. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189:1374-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt M, Zogheib E, Rozé H, et al. The PRESERVE mortality risk score and analysis of long-term outcomes after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:1704-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klinzing S, Wenger U, Steiger P, et al. External validation of scores proposed for estimation of survival probability of patients with severe adult respiratory distress syndrome undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy: a retrospective study. Crit Care 2015;19:142. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hilder M, Herbstreit F, Adamzik M, et al. Comparison of mortality prediction models in acute respiratory distress syndrome undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and development of a novel prediction score: the PREdiction of Survival on ECMO Therapy-Score (PRESET-Score). Crit Care 2017;21:301. [Crossref] [PubMed]