Sonic hedgehog promotes endothelial differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells via VEGF-D

Introduction

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) have been proven effective for therapeutic angiogenesis in in-vitro and in-vivo animal experiments and in clinical settings (1-3). The angiogenic properties of BMSCs can be attributed to direct differentiation into endothelial cells (ECs) and the paracrine effect as well (4). It has been reported that only a very small fraction of BMSCs could differentiate into ECs in vitro (3). There have been few studies demonstrating the concrete EC oriented differentiation of MSCs in vivo (5).

Sonic hedgehog (Shh) gene is an angiogenic growth factor that specifically regulates vascular tube formation (6,7). Several studies have indicated that although Shh remained silent postnatally, this gene could be reactivated in response to tissue ischemia, exerting promotional effect on the angiogenic genes (8,9). Roncalli et al. (9) observed that bone-marrow-derived progenitor cells (BMPCs), cultured in conditioned medium collected from fibroblasts transfected with Shh-overexpressed plasmids, exhibited enhanced in vitro tube-forming ability, and up-regulated angiogenic genes expression. In addition, they presented more incorporation of BMPCs into vessels in myocardial infarction area after application of Shh-plasmids. In another study, researchers witnessed Shh-induced up-regulation of angiogenic growth factors in MSCs and improved blood vessel density in infarcted area (10). These studies both indicated the promoted pro-angiogenic ability of bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells with Shh gene overexpression; however, with no direct evidence of the endothelial differentiation in bone marrow-derived stem/progenitor cells induced by Shh.

Considering the role of Shh in postnatal angiogenesis, it may be effective to establish an endothelial differentiation method in MSCs by up-regulating Shh. We tested this hypothesis by in vitro tube formation assay and in vivo Matrigel assay. Furthermore, this study elaborated the mechanism of endothelial differentiation in Shh-overexpressed MSCs using mRNA sequencing analysis.

Methods

Animals

All animals received humane care in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Research Animals established by Soochow University. Eight- week-old severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice and 3-week-old Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from Model Animal Research Center of Nanjing University, China (11). SCID mice and SD rats were housed in standard polycarbonate cages in the Animal Facility of Soochow University. Animals were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle as well as provided with free access to feed and water.

BMSCs isolation and characterization

Mesenchymal stem cells were isolated from bone marrow of 3-week-old SD rat femur and tibia as previously described (12). Briefly, rat femur and tibia were collected and flushed using DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, China). Thereafter, cells were centrifuged at 200 RCF for 5 mins and re-suspended. Cells were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. MSC colonies appeared within 8−10 days. The phenotype of MSCs was identified by flow cytometry.

BMSCs were identified by flow cytometry as previously described (13). MSCs at passage 3 were stained with immunofluorescence antibodies against CD29, CD11b/c, MHCII, and CD90 (Abcam). The cells were detected by flow cytometry, and data were analyzed by FlowJo software (FlowJo, LCC, USA).

Reconstruction of Shh plasmid and lentivirus transfection

Lentiviral vector containing Shh was constructed using vector pCDH-CMV-MCS-EF1-copGFP as backbone. Shh fragments were amplified from rat genomic DNA using the primers as follows: sense, 5'-CGGAATTCGCCACC ATGCTGCTGCTGCTGGCCAG-3'; anti-sense, 5'-CGCGGATCC TCAGCTGGACTTGACTGCCATT-3'. Then Shh fragments were ligated with vector which was digested with EcoRI and BamHI (NEB, USA). The reconstructed plasmid was verified by Sanger sequencing. HEK293NT cells were used for lentiviral production. Briefly, HEK293NT cells were co-transfected with control vector or lentiviral plasmid carrying Shh fragments, along with lentiviral packaging mix. Culture medium were collected and incubated with polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000) overnight before centrifugation. Purified lentivirus was stored at –80 °C.

BMSCs at passage 3 seeded in 6 cm dishes were used for lentivirus transfection. Cells were washed by PBS twice before transfection. Then, 2,000 µL of culture medium, 100 µL of purified lentivirus and 2 µL of polybrene were added into the cell dish. MSCs transfected with empty vector and Shh are refered as MSCNC and MSCShh, respectively. MSCNC and MSCShh are used for the following assays at 2 different time points post lentivirus transfection, 3- and 7-day.

mRNA expression level determined by real time reverse-transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

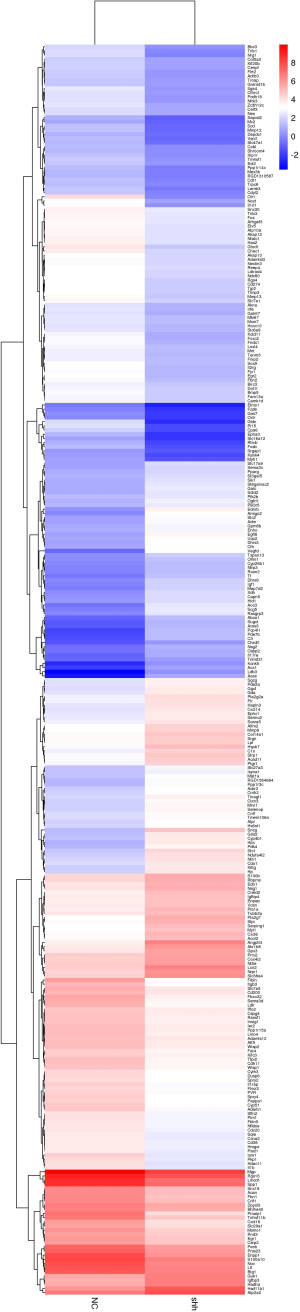

Real-time RT-qPCR was used to determine the mRNA expression, namely Shh, Ptch, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), angiopoietin-1 (Ang-1), IGF, and VEGF, in MSCs after transfected with empty lentivirus or Shh lentivirus. In addition, expression level of endothelial markers, CD31 and Ve-cadherin, in MSCs transfected with empty lentivirus or Shh lentivirus were detected using RT-qPCR. Cell samples were prepared as follows: MSCs transfected with empty lentivirus or Shh lentivirus were collected 3 and 7 days after transfection. Total RNA of cell samples was extracted using Trizol reagent (Ambion by Life Technologies, USA) and then purified according to the manufacturer’s protocol (QIAGEN, USA) as previously described (14). Then, cDNA was converted from extracted total RNA using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TAKARA, Tokyo, Japan). Then, a total 2 µL of cDNA sample was used for qPCR, which was performed using Power Syber Green (Applied Biosystems, USA) under the StepOne-Plus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). GAPDH was used to normalize the results. The sequences of primers used in qPCR are presented in Table 1. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to evaluate the relative quantification of changes in the expression of target genes.

Full table

Western blot

The expression of Shh protein in MSCs and culture medium of MSCs were determined using western blot. Seven days after Shh-lentivirus or empty-lentivirus transfection, MSCs were washed twice by PBS and culture medium were changed. Three days later, the protein was extracted from MSCs and culture medium of MSCs. Then, protein was lysed with M-PER reagents and Halt Protease Inhibitor Cocktail kits (Pierce, USA). The concentration of extracted protein was measured by BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, China). Then, the extracted protein was separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked using Tween 20/PBS including 5% skim milk, and then incubated with primary antibody against Shh (1:100, Abcam, USA) and β-actin (1:1,000, Beyotime Biotechnology, China) and followed by the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000; Beyotime Biotechnology, China). The protein labeled bands were determined using the enhanced chemiluminescent kit and analyzed using the Scion Image Software (Scion, USA). The intensity of protein bands was evaluated with Image J (National Institutes of Health, USA). The intensity of the protein bands was quantified relative to the β-actin bands from the same sample.

Tube formation assay

After the determination of Shh mRNA and its down-stream mRNA expression, the in vitro angiogenic ability of MSCs was examined by tube formation assay as previously described (15). Briefly, MSCs were transfected with empty lentivirus or Shh lentivirus and cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Three days or seven days after transfection, 2×104 MSCNC or MSCShh were suspended using 100 µL EBM-2 culture medium. Before MSCs were seeded on a 96-well plate, 50 µL Matrigel matrix (BD, Bedford, MA, USA) was added to each well beforehand, and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. After seeded on Matrigel, MSCs were incubated for 6 hours at 37 °C. Tube length and mashes numbers were measured by Image J software. The tube length and mashes numbers in each high-power field (HPF) were manually calculated and presented as means ± SD.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min and then blocked with 0.05% Tween and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were incubated with 1:100 diluted anti-PECAM antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-VE-cadherin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and anti-vWF (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) overnight at 4 °C. Cells were then washed three times with PBS to remove the unbound antibody and then incubated with 1:1,000 diluted anti-rat IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, USA) or anti-goat IgG Alexa Fluor 594 (Invitrogen, USA) in dark for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed twice with PBS, and then stained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Invitrogen, USA) for 5min. Cells were then sealed and observed with a fluorescence microscope (Olympus, Japan).

In vivo endothelial differentiation of BMSCs

The neovascularization potential of MSCs was examined using Matrigel plug in immunodeficient SCID mice, in which dynamic and long-term neovascularization of implanted MSCs could be observed (16). Considering their stronger endothelial differentiation ability than 3-day MSCShh, 7-day MSCShh were used for the in vivo Matrigel plug model. Generally, a total of 1×104 7-day MSCNC or MSCShh suspended in 100 µL DEME/F-12 medium were mixed with 100 µL Matrigel. Then 200 µL suspension was injected subcutaneously into dorsal region of nude mouse (16). Two weeks after injection, Matrigel plugs were harvested and stained with anti-rat CD31 antibody (Abcam, Catalog No. ab119339). In this assay, we used anti-CD31 antibody whose species reactivity only contains rat, human and cow, but not mouse.

mRNA sequencing by Illumina HiSeq

Total RNA of each sample was extracted using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen)/RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen)/other kits. Total RNA of each sample was quantified and qualified by Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), NanoDrop (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., MA, USA) and 1% agrose gel. 1 µg total RNA with RIN value above 7 was used for following library preparation. Next generation sequencing library preparations were constructed according to the manufacturer’s protocol (NEBNext® Ultra™ RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina®). Then libraries with different indices were multiplexed and loaded on an Illumina HiSeq instrument according to manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing was carried out using a 2×150 bp paired-end (PE) configuration; image analysis and base calling were conducted by the HiSeq Control Software (HCS) + OLB + GAPipeline-1.6 (Illumina) on the HiSeq instrument. The sequences were processed and analyzed by JINGYUN. Differential expression analysis used the DESeq Bioconductor package, a model based on the negative binomial distribution. After adjusted by Benjamini and Hochberg’s approach for controlling the false discovery rate, P value of genes were set <0.05 to detect differential expressed ones. GO-TermFinder was used to identify Gene Ontology (GO) terms that annotate a list of enriched genes with a significant P value less than 0.05. KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) is a collection of databases dealing with genomes, biological pathways, diseases, drugs, and chemical substances (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KEGG). We used scripts in house to enrich significant differential expression gene in KEGG pathways.

Gene knockdown by small interfering RNA (siRNA)

Vascular endothelial growth factor D (VEGF-D) siRNA (sense, 5'-GCUGUGGGAUAACACCAAATT-3'; antisense, 5'-UUUGGUGUUAUCCCACAGCTT-3') were designed and synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). MSCNC or MSCShh were then transfected with scramble siRNA and VEGF-D siRNA for 24 h. Then the cells were harvested for real-time PCR or tube formation analysis. Each experiment was performed separately 3 times.

Statistical analyses

All results are expressed as mean ± SD. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software, via Student’s unpaired t test for the difference between two groups or one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple group comparison. Differences were considered significant at P<0.05.

Results

MSCs culture and successful transfection of Shh lentivirus in MSCs

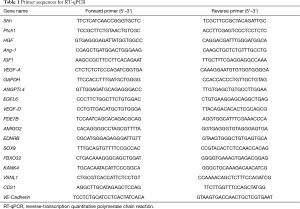

MSCs changed their morphologies into spindle-shape and were adherent to plastic dishes at day 3 (Figure 1A). Cell surface markers were identified by flow cytometry. Results presented that MSCs were positive for CD90 and CD29, and negative for CD11b/c and MHCII (Figure 1B).

About 95% of BMSCs expressed green fluorescent protein (GFP) after lentiviral infection, which suggests the success of packaging and cell infection (Figure 1C). Accordingly, RT-qPCR has proved the augmentation of Shh mRNA level in BMSCs. Shh mRNA expression level had increased by about 3,000-fold or 5,000-fold in 3-day MSCShh and 7-day MSCShh compared with MSCNC (Figure 1D). Consistently, Shh protein expression in 7-day MSCShh presented about 1.2-fold increase compared with 7-day MSCNC (Figure 1E,1F). However, no Shh protein level was observed in the culture medium of 7-day MSCShh and 7-day MSCNC (Figure 1G).

Angiogenic factors were increased in MSCs by overexpressing Shh

We further determined the expression levels of several pro-angiogenic mRNA in BMSCs after 3 or 7 days of Shh transfection. The expression level of patched 1 (Ptch1), the ligand of Shh, has increased by more than 2-fold in MSCShh compared with MSCNC at both times point of 3-day and 7-day post transfection (P<0.001, 3-day MSCShhvs. 3-day MSCNC and 7-day MSCShhvs. 7-day MSCNC), while Ptch1 expression level showed no statistical significance between day 3 and day 7 post transfaction (Figure 2A). The expression levels of HGF (Figure 2B) and Ang-1 (Figure 2C) augmented by approximately 2-fold (HGF; P<0.05, 3-day MSCShhvs. 3-day MSCNC; P<0.001, 7-day MSCShhvs. 7-day MSCNC) and 1.5-fold (Ang-1; P<0.001, 3-day MSCShhvs. 3-day MSCNC and 7-day MSCShhvs. 7-day MSCNC) post transfection, with no statistical significance between the two-time points post transfection. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) mRNA expression increased gradually after lentivirus transfection. IGF1 presented consistent augmentation after transfection, with 1.66-fold at day 3 and 2.18-fold at day 7, respectively (Figure 2D; P<0.05, 3-day MSCShhvs. 7-day MSCShh). VEGF-A mRNA expression (Figure 2E) manifested mild increase at day 3 (P<0.05, 3-day MSCShhvs. 3-day MSCNC), and marked increase at day 7 after transfection (P<0.001, 7-day MSCShhvs. 7-day MSCNC).

In vitro angiogenic activity of MSCs were augmented by the overexpression of Shh

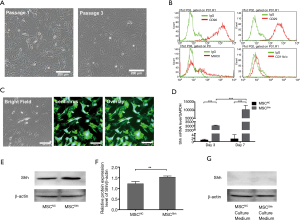

As shown in Figure 3A, MSCNC presented limited tube-forming ability, while Shh transfection has successfully induced BMSCs to form tubes on Matrigel. Moreover, the enhanced angiogenic ability of MSCShh presented a time-dependent manner, with 20.64±2.29 mm tube formed by 3-day MSCShhvs. 39.39±3.68 mm formed by 7-day MSCShh (Figure 3B; P<0.001). Accordingly, mashes formed by BMSCs manifested similar tendency with tube length. 1.33±0.33 mashes and 0.67±0.33 mashes were formed by 3-day MSCNC and 7-day MSCNC, respectively. Mashes numbers were significantly increased after transduced with Shh, with 9.67±1.45 mashes and 55.33±3.53 mashes formed by 3-day MSCShh and 7-day MSCShh, respectively (Figure 3C; P<0.001).

Endothelial specific markers were highly expressed in Shh-overexpressed MSCs

Fluorescent microscopy analysis observed relatively low levels of CD31 and VE-cadherin in MSCNC (Figure 3D). By contrast, CD31 and VE-cadherin displayed strong green fluorescent signal in MSCShh (Figure 3D), indicating that Shh-overexpressed MSCs underwent endothelial differentiation. Consistently, RT-qPCR indicated that expression of CD31 and VE-cadherin in MSCShh increased by 1.58- and 1.55-fold compared with MSCNC, respectively (Figure 3E).

Increased in vivo neovascularization potential of MSCs by overexpression of Shh

Matrigel plug was harvested 14 days after subcutaneous injection and immunochemistry staining using anti-rat CD31 antibody was performed. As presented in Figure 3F, the functional vessels were increasingly formed by 7-day MSCShh compared with MSCNC (Figure 3G; P<0.001), indicating that Shh transduction could induce MSCs differentiating into ECs in vivo.

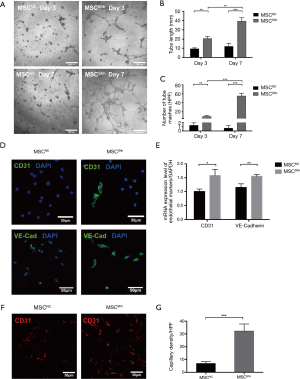

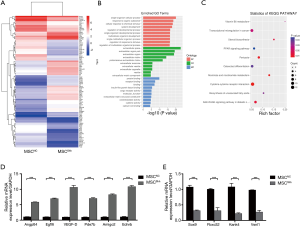

Analysis of differentially-expressed mRNA between MSCNC and MSCShh

We obtained total mRNA of MSCNC and MSCShh for high-throughput sequencing. Heatmap analysis showed the distribution of differentially-expressed mRNA in both MSCNC and MSCShh (Figure S1 and Figure 4A). Three hundred and thirty differentially-expressed mRNA were detected (fold change >2.0, P value <0.05) (Figure S1). One hundred and thirty-eight mRNA were up-regulated and 192 mRNA were down-regulated compared with MSCNC. Among these, 100 top differentially-expressed mRNA were manifested for clear observation (Figure 4A). Interestingly, from the heat map we observed that the expression of genes related with angiogenesis in MSCShh, such as Vegfd, Angptl4, Egfl6, Pde7b, Amigo2 and Ednrb, were much higher than those in MSCNC.

The GO analysis was classified into three parts: biological process (BP), cellular component (CC) and molecular function (MF). We have listed 3 parts of the top 10 generally changed GO terms (Figure 4B). Those meaningful BP terms, CC terms, and MF terms were related to response to stress, response to oxygen levels, receptor binding, cargo receptor activity and CX3C chemokine binding. Moreover, 10 pathways were significantly enriched by the 330 differentially expressed genes (Figure 4C), including PPAR signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, p53 signaling pathway and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction.

Validation of differentially-expressed genes by real time PCR

To verify the molecular signature between MSCNC and MSCShh, a total of 10 genes were selected for validation by qPCR (Figure 4D,4E). The genes were selected based on fold change differences, participation in migration, cell proliferation and/or involvement in vasculogenesis. All tested genes exhibited a high agreement with the high-throughput sequencing output. The expressions of Angptl4, Egfl6, VEGF-D, Pde7b, Amigo2 and Ednrb were significantly higher in MSCShh compared to MSCNC (Figure 4D; P<0.001). Sox9, Fbxo32, Kank4 and Vsnl1 expressions were significantly lower in MSCShh compared to MSCNC (Figure 4E; P<0.001).

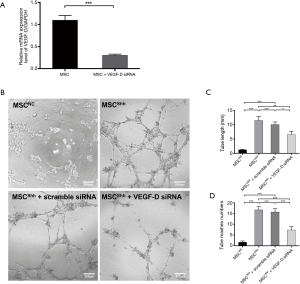

Tube formation abilities were inhibited in Shh-overexpressed MSCs by knocking down of VEGF-D

We first confirmed the knocking down efficiency of VEGF-D siRNA by qPCR. It showed that VEGF-D siRNA could inhibit the expression of VEGF-D by about 70% (Figure 5A). After transfecting MSCShh with VEGF-D siRNA, the cells presented attenuated tube-forming ability (Figure 5B). Accordingly, mashes formed by MSCShh with VEGF-D siRNA transfection manifested the tube length of 6.58±1.13 mashes compared with MSCShh 11.51±1.38 mashes, respectively (Figure 5C, P<0.01). Mashes numbers had been significantly decreased after Shh-overexpressed MSCs were transduced with VEGF-D siRNA, with 7.33±1.53 mashes vs. 16.67±1.53 mashes formed by MSCShh with or without VEGF-D siRNA treatment, respectively (Figure 5D, P<0.001).

Discussion

This study presents several new findings. First, it gives solid evidence that bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells with upregulated Shh could differentiate into ECs both in vitro and in vivo. Second, it demonstrates that Shh could enhance the mRNA expression level of VEGF-D, which is important for endothelial differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells. In addition, it revealed that Shh activates several pathways that are highly related to endothelial differentiation ability of mesenchymal stem cells, such as PPAR signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, p53 signaling pathway and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction.

BMSCs represent a great hope for ischemic diseases. However, their therapeutic usage is still restricted because of the limited differentiation ability. Researchers have been struggling to establish a reliable endothelial differentiation, but often have gotten controversial conclusions (17). Various culture conditions such as VEGF addition (18-20), serum deprivation (21), high cell plating density (22) and mechanical stimulation (23) could induce endothelial differentiation of MSCs in vitro. Dr. Oswald induced the differentiation of MSCs into endothelial-like cells by addition of 50 ng/mL of VEGF, showing a strongly increased expression of kinase insert domain receptor (KDR) and fms related tyrosine kinase 1 (Flt-1) (18). Further study proved that combined stimulation of shear stress and VEGF resulted in more profound EC oriented differentiation of MSCs in comparison to any individual stimulation (23). There are also a few studies demonstrating that engineered biomaterials can enhance endothelial differentiation of MSCs (24). Very recently, Dr. Liu genetically engineered a protein containing VEGF mimicking peptide, which effectively promoted endothelial differentiation of MSCs (25). However, very rare reports detected differentiation of MSCs into ECs in vivo. Patrick Au et al. proved that MSCs couldn’t differentiate into ECs in vivo, and could merely function as perivascular cell precursors (26).

Shh is an angiogenic growth factor that specifically regulates vascular tube formation (6,7). Although being silenced in post-natal life, reactivation of the Shh signaling pathway plays a crucial regulatory role on injury-induced angiogenesis (10). Shh gene therapy could enhance angiogenesis in peripheral ischemia (27) and myocardial ischemia model (9), through upregulation of angiogenic and vasculogenic factors, such as VEGF, Ang-1 and SDF-1α. More recently, Dr. Ashraf proved that genetic modification of MSCs with Shh improves their survival and angiogenic potential in the ischemic heart via iNOS/netrin/PKC pathway (10), but this study didn’t investigate the real trace of transplanted MSCs in the ischemic myocardium. Thus, evidence for reliable differentiation of MSCs into ECs in vivo is urgently needed. In this study, we over-expressed Shh in MSCs to induce cell differentiation towards the endothelial lineage. We have found that MSCs with Shh overexpression could form tubes in Matrigel in vitro by themselves, and grow into vessels in Matrigel plug underneath the skin of nude mice. Importantly, upregulation of Shh in MSCs activates multiple angiogenic pathways and affects cell fate, helping endothelial commitment.

As presented in Figure 2, Shh-overexpressed cells exhibited statistically higher Ptch1 compared to negative groups. We observed increased gene expression levels of VEGF-A, IGF-1, HGF and Ang-1 at 3 and 7 days of differentiation compared to negative control groups. In addition, there was significant difference in VEGF-A and IGF-1 gene expression between the 3 and 7 days. MSCShh could form remarkable tube structures in Matrigel, while MSCNC just sprouted several branches, which provides reliable and solid evidence of endothelial differentiation of BMSCs in vitro. Consistent with the expression pattern of angiogenic genes, the number of mashes and tube length were significantly higher in 7-day MSCShhvs. 3-day MSCShh. Therefore, seven days of differentiation may be right time point for endothelial induction of BMSCs. We used 7-day induced BMSCs for further experiments. Shh-overexpressed MSCs formed neovessels in Matrigel plug after subcutaneous transplantation in nude mice, while few vessels were detected in the negative control group. This provides the direct evidence of endothelial differentiation of BMSCs in vivo, which is rarely demonstrated before.

Activation of Shh signaling pathway contributed much to improve functions of MSCs, including survival and neovascularization. However, limited studies have been conducted on the mechanism how Shh signaling pathway affected MSCs. This study further explored the mRNA expression profiling of BMSCs upon Shh overexpression. We identified 330 differentially-expressed mRNAs in Shh-overexpressed MSCs, with enriched functions of response to stress and receptor binding by GO analysis and enriched PPAR signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway and p53 signaling pathway by pathway analysis. Among these genes, the most highly-upregulated gene is VEGF-D, with the fold change of 16.9. Reviewing the literatures on the relationship of Shh and VEGFs, we could find reports on Shh/VEGF-A (28-30) and Shh/VEGF-C (31), but there is no report regarding Shh and VEGF-D. To further validate our discovery, we performed qPCR first. And we found a 10-fold change of VEGF-D after Shh overexpression. Then, we performed tube formation assay using MSCShh and MSCNC after knocking down of VEGF-D. The tube formation ability of MSCShh was partially abolished by VEGF-D siRNA, which reflected that Shh promoted angiogenic function of MSCs also via VEGF-D.

Except for VEGF-D, others genes like Angptl4 (32,33), Egfl6 (34), Pde7b (35), Amigo2 (36) and Ednrb (37,38) were also reported to be involved in the process of angiogenesis. These were all detected to be upregulated in Shh-overexpressed MSCs. Angptl4 (Angiopoietin-like 4) plays a prominent role in promoting the angiogenesis and vessel permeability (32,33). Moreover, EGFL6 promotes angiogenesis via ERK, STAT3, and integrin signaling cascades (34), and also acts as an angiogenic switch that is involved in tumor angiogenesis (39).

Conclusions

We can conclude that Shh could promote endothelial differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells by Shh/VEGF-D axis.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81770260), Jiangsu Province’s Key Discipline/Laboratory of Medicine (XK201118), National Clinical Key Specialty of Cardiovascular Surgery, Jiangsu Clinical Research Center for Cardiovascular Surgery (BL201451), and Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20151212).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The experiment protocols were approved by the Ethic Committee of Soochow University (reference number: SZUM2008031233).

References

- Karantalis V, Suncion-Loescher VY, Bagno L, et al. Synergistic Effects of Combined Cell Therapy for Chronic Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:1990-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang PP, Yang XF, Li SZ, et al. Randomised comparison of G-CSF-mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells versus bone marrow-mononuclear cells for the treatment of patients with lower limb arteriosclerosis obliterans. Thromb Haemost 2007;98:1335-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Watt SM, Gullo F, van der Garde M, et al. The angiogenic properties of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and their therapeutic potential. Br Med Bull 2013;108:25-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma T, Sun J, Zhao Z, et al. A brief review: adipose-derived stem cells and their therapeutic potential in cardiovascular diseases. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017;8:124. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baksh D, Song L, Tuan RS. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: characterization, differentiation, and application in cell and gene therapy. J Cell Mol Med 2004;8:301-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanda S, Mochizuki Y, Suematsu T, et al. Sonic hedgehog induces capillary morphogenesis by endothelial cells through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. J Biol Chem 2003;278:8244-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vokes SA, Yatskievych TA, Heimark RL, et al. Hedgehog signaling is essential for endothelial tube formation during vasculogenesis. Development 2004;131:4371-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pola R, Ling LE, Aprahamian TR, et al. Postnatal recapitulation of embryonic hedgehog pathway in response to skeletal muscle ischemia. Circulation 2003;108:479-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Roncalli J, Renault MA, Tongers J, et al. Sonic hedgehog-induced functional recovery after myocardial infarction is enhanced by AMD3100-mediated progenitor-cell mobilization. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:2444-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed RP, Haider KH, Shujia J, et al. Sonic Hedgehog gene delivery to the rodent heart promotes angiogenesis via iNOS/netrin-1/PKC pathway. PLoS One 2010;5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fu S, Wang J, Sun W, et al. Preclinical humanized mouse model with ectopic ovarian tissues. Exp Ther Med 2014;8:742-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Z, Yang J, Yan W, et al. Pretreatment of Cardiac Stem Cells With Exosomes Derived From Mesenchymal Stem Cells Enhances Myocardial Repair. J Am Heart Assoc 2016.5. [PubMed]

- Zhang Y, Lei W, Yan W, et al. microRNA-206 is involved in survival of hypoxia preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells through targeting Pim-1 kinase. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016;7:61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- You J, Sun J, Ma T, et al. Curcumin induces therapeutic angiogenesis in a diabetic mouse hindlimb ischemia model via modulating the function of endothelial progenitor cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2017;8:182. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Zhang X, Zhao Z, et al. Regulatory roles of interferon-inducible protein 204 on differentiation and vasculogenic activity of endothelial progenitor cells. Stem Cell Res Ther 2016;7:111. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li Z, Hu S, Ghosh Z, et al. Functional characterization and expression profiling of human induced pluripotent stem cell- and embryonic stem cell-derived endothelial cells. Stem Cells Dev 2011;20:1701-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vittorio O, Jacchetti E, Pacini S, et al. Endothelial differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells: when traditional biology meets mechanotransduction. Integr Biol (Camb) 2013;5:291-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oswald J, Boxberger S, Jorgensen B, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells can be differentiated into endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells 2004;22:377-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Benavides OM, Petsche JJ, Moise KJ Jr, et al. Evaluation of endothelial cells differentiated from amniotic fluid-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A 2012;18:1123-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen MY, Lie PC, Li ZL, et al. Endothelial differentiation of Wharton's jelly-derived mesenchymal stem cells in comparison with bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Hematol 2009;37:629-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oskowitz A, McFerrin H, Gutschow M, et al. Serum-deprived human multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are highly angiogenic. Stem Cell Res 2011;6:215-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whyte JL, Ball SG, Shuttleworth CA, et al. Density of human bone marrow stromal cells regulates commitment to vascular lineages. Stem Cell Res 2011;6:238-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bai K, Huang Y, Jia X, et al. Endothelium oriented differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells under chemical and mechanical stimulations. J Biomech 2010;43:1176-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Poh CK, Shi Z, Lim TY, et al. The effect of VEGF functionalization of titanium on endothelial cells in vitro. Biomaterials 2010;31:1578-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim Y, Liu JC. Protein-engineered microenvironments can promote endothelial differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in the absence of exogenous growth factors. Biomater Sci 2016;4:1761-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Au P, Tam J, Fukumura D, et al. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells facilitate engineering of long-lasting functional vasculature. Blood 2008;111:4551-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palladino M, Gatto I, Neri V, et al. Pleiotropic beneficial effects of sonic hedgehog gene therapy in an experimental model of peripheral limb ischemia. Mol Ther 2011;19:658-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrow D, Cullen JP, Liu W, et al. Sonic Hedgehog induces Notch target gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells via VEGF-A. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009;29:1112-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- White AC, Lavine KJ, Ornitz DM. FGF9 and SHH regulate mesenchymal Vegfa expression and development of the pulmonary capillary network. Development 2007;134:3743-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Henno P, Grassin-Delyle S, Belle E, et al. In smokers, Sonic hedgehog modulates pulmonary endothelial function through vascular endothelial growth factor. Respir Res 2017;18:102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wei R, Lv M, Li F, et al. Human CAFs promote lymphangiogenesis in ovarian cancer via the Hh-VEGF-C signaling axis. Oncotarget 2017;8:67315-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma T, Jham BC, Hu J, et al. Viral G protein-coupled receptor up-regulates Angiopoietin-like 4 promoting angiogenesis and vascular permeability in Kaposi's sarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010;107:14363-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gealekman O, Burkart A, Chouinard M, et al. Enhanced angiogenesis in obesity and in response to PPARgamma activators through adipocyte VEGF and ANGPTL4 production. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008;295:E1056-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chim SM, Kuek V, Chow ST, et al. EGFL7 is expressed in bone microenvironment and promotes angiogenesis via ERK, STAT3, and integrin signaling cascades. J Cell Physiol 2015;230:82-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sadhu K, Hensley K, Florio VA, et al. Differential expression of the cyclic GMP-stimulated phosphodiesterase PDE2A in human venous and capillary endothelial cells. J Histochem Cytochem 1999;47:895-906. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park H, Lee S, Shrestha P, et al. AMIGO2, a novel membrane anchor of PDK1, controls cell survival and angiogenesis via Akt activation. J Cell Biol 2015;211:619-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Takeo M, Lee W, Rabbani P, et al. EdnrB Governs Regenerative Response of Melanocyte Stem Cells by Crosstalk with Wnt Signaling. Cell Rep 2016;15:1291-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stobdan T, Zhou D, Ao-Ieong E, et al. Endothelin receptor B, a candidate gene from human studies at high altitude, improves cardiac tolerance to hypoxia in genetically engineered heterozygote mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:10425-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noh K, Mangala LS, Han HD, et al. Differential Effects of EGFL6 on Tumor versus Wound Angiogenesis. Cell Rep 2017;21:2785-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]