Surgical management of chronic diaphragmatic hernias

Introduction and etiology

The first description of a chronic diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) was done by Sennertus in 1541, who described a soldier with stomach herniating into his chest 7 months after an injury (1).

By definition, a diaphragmatic hernia (DH) is the migration into the thorax of viscera which are normally confined into the peritoneal cavity, usually as a consequence of a traumatic event.

A first DH’s classification criteria concerns the temporal parameter of its developing and diagnosis. The Carter’s scheme (2) recognizes: (I) acute (the acute phase is comprises between the original trauma development and the recovery of the patient); (II) latent (this phase starts from the recovery during which the patient may or may not be symptomatic), and obstructive DH [this phase starts when the intrathoracic herniated viscera become incarcerated, with potential high-risk of necrosis, ischemia and/or perforation (Figure 1)].

Although traumatic DHs have been reported in approximately 0.5% to 1.6% of patients hospitalized for blunt trauma (3), the precise incidence of this injury seems to be likely higher than that reported by the historical series. Eighty percent of DHs are found on the left side and 20% in the right; in less than 3% of cases, DH may be bilateral (4). The incidence of DHs after a penetrating trauma is 20–59% in case of gunshot, and 15–32% in stab wounds (5).

At the same time, it is very difficult to determine the real incidence of CDHs. Their development is directly related to the difficulty to diagnose an acute DH, following a thoracic or thoraco-abdominal injury. Therefore, a CDH is the sequelae of an undiagnosed and untreated diaphragmatic injury, during an acute traumatic event. Thus, it is quite impossible to ascertain how many of these acute DHs will become chronic.

From the dynamic point of view, CDHs may result as the consequence of a penetrating or a blunt trauma.

Penetrating trauma

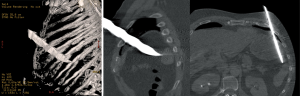

The reported acute DH’s incidence after a penetrating thoraco-abdominal trauma may vary between 3.4% and 47%; of these, 7% to 26% may see their acute hernia undiagnosed (6-8). Currently, the most frequent penetrating thoracic traumas are caused by knife wounds (Figures 2,3).

The traditional management of acute penetrating thoraco-abdominal trauma usually requires a prompt surgical exploration, which led to an increase in the recognition (and therefore treatment) of diaphragmatic involvement in such acute setting. Nowadays, a more aggressive non-operative management of penetrating traumas increases the risk of seeing undiagnosed possible diaphragmatic injuries.

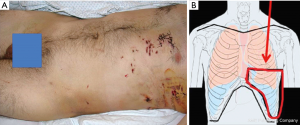

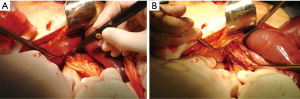

Finally, injuries (especially multiple, Figure 4A) to the lower chest (Figure 4 B) pose the greater risk for diaphragmatic lesions.

Blunt trauma

In blunt thoraco-abdominal trauma, the overall incidence of DHs has been reported to be between 0.8% and 20% (8-11). A great percentage of these hernias are acutely missed, due in part to the severity of the other associated injuries (12-14). The recent radiological preoperative standardization (especially by ultrasound and helical CT) has led to decrease the incidence of undiagnosed DHs (15,16).

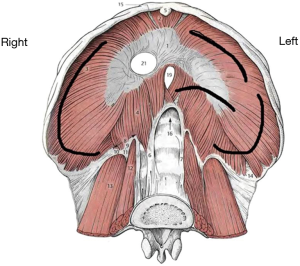

DHs’ distribution after blunt trauma is as follows: 50% to 80% are isolated to the left hemidiaphragm and 12% to 40% to the right one; 1% to 9% are bilateral (13,17,18). This preponderance for left sided injuries is thought to be related to the protective effect of the bare area of the liver in contact with the diaphragm on the right, dissipating some traumatic forces (19). The site of diaphragmatic injury usually is the weak area where the lumbar and costal diaphragmatic leaflets are fused during its embryological development. After a left-sided blunt trauma, the lesions are predominantly posterolateral, with radial and medial extension towards the central tendon (20). However, due to the tremendous forces engaged in generating the trauma, diaphragmatic disruptions after blunt trauma usually result in larger tissue defects compared to those caused by penetrating traumas. Figure 5 schematically shows the most common sites of diaphragmatic injuries after a blunt trauma.

Pathophysiology of CDH development

Some penetrating or blunt injuries may create a small diaphragmatic tissue defect, which is not recognized at the time of the trauma, or is not treated because of the lack of clinical symptoms.

Different forces are involved in peritoneal viscera migration into the chest through a diaphragmatic defect: the chest’s negative intrapleural pressure and the intra-abdominal positive one. The first attracts intra-abdominal contents upwards, the latter pushes them in the same direction. Typically, there is a pressure gradient of 7–10 cmH2O, effecting this process, but this gradient may increase during deep inspiration, coughing or during pregnancy (21). The combination of these 2 forces results in the progressive enlargement of the diaphragmatic defect along with intra-thoracic displacement of abdominal contests. Several herniated organs have been described: omentum, stomach, small bowel, spleen and colon at the left-side; liver, colon, small bowel and omentum in the right-sided hernias. Sometimes, especially in large defects, more than one organ may be involved in a single hernia.

With the increase of the diaphragmatic defect, its contribution to the respiratory function tends gradually to decrease; decreased exercise tolerance as well as progressing dyspnoea are the common symptoms at this time. Moreover, abdominal contents intrathoracic displacement may compress pulmonary parenchyma and also shift contralaterally the mediastinum, with possible venous return impairment. This entire process may take days, weeks, months or years from the initial traumatic event.

Anyway, major morbidity and mortality in CDHs is related to the obstructive phase development: in case of large diaphragmatic defects, a volvulus may develop, while strangulation and/or perforation are more common in case of large volumes of tissue herniated in the chest through a small diaphragmatic defect (22-24).

Symptoms at presentation may vary widely. In some cases, CDH is incidentally discovered performing radiological examinations for unrelated reasons; in such patients, clinical symptoms are very rare. An history of an antecedent thoracic or abdominal trauma is generally observed.

On the other hands, symptomatology may be related to the gastrointestinal organs, respiratory tract or may be a non-specific general pain.

Dramatic symptoms are related to severe complication of gastrointestinal viscera herniated into the chest: obstruction, ischemia and/or perforation are the most frequent ones (Figures 1,6). In case of large and rapid viscera herniation, significant respiratory and cardiovascular symptoms may also mimic a tension pneumothorax (25-27).

Diagnosis

The key points in CDH’s diagnosis are: (I) the history of an antecedent blunt (in the majority of cases) or penetrating thoracic or thoraco-abdominal trauma, along with the (II) demonstration of intra-abdominal viscera herniation within the chest cavity.

It is sometimes difficult to ascertain a previous blunt trauma, since it may be very remote as well as characterized by very few clinical symptoms. Furthermore, as reported before, symptoms may vary widely and may be completely non-specific (mimicking peptic or gallbladder disease). Severe chest/abdominal pain, dyspnoea and acute respiratory impairment, fever, tachycardia and dehydration are the most common complaints in case of large CDHs in the obstructive phase. Once these symptoms are observed, a prompt medical resuscitation treatment is needed before the surgical exploration.

Radiological evaluation

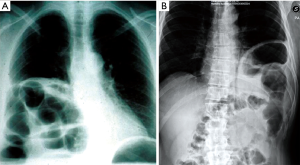

Although chest X-ray diagnostic utility has been highlighted in acute DHs, the role of this radiological procedure in chronic ones is still debated. The most important remark is the presence of abdominal viscera in the chest cavity (Figures 7,8), along with the collar sign, which is identified as the appearance of a focal constriction at the site where abdominal viscera traverse the diaphragm.

The recent helical CT introduction has led to a dramatic improvement in CDHs’ diagnostic. It has, in fact, demonstrated an improved sensitivity (70–100%) and specificity (75–100%), with some differences between right and left hernias, with improved detection on the left side (28-31). This improvement is not only due to the CT’s higher resolution, but also to the possibility to reformat the images in coronal and sagittal views. This mostly makes possible the correct identification of the diaphragm injury, along with the abdominal viscera herniation in the chest cavity direct demonstration.

As for CT, also the thoracic MRI great advantage is the possibility to reformat the images in sagittal and coronal views. In particular, T1-weighted imaging is the best modality to differentiate diaphragm from adjacent tissues, and therefore to demonstrate diaphragmatic defects along with viscera protruding through them (32,33).

The use of CT (and MRI) has generally replaced fluoroscopy, even if sometimes, the demonstration of oral or rectal contrast in the viscera herniated into the chest cavity demonstrated to be diagnostic for CDHs.

Surgical management

In case of CDH, the surgical approach should be immediate; a delay in the intervention can be admitted only in patients with severe comorbidities. Adequate water and electrolyte rebalancing is needed, especially in case of profound dehydration caused by gastrointestinal ischemia or necrosis.

A CDH is traditionally treated trough a transthoracic or a transabdominal approach, even if with the recent minimally invasive techniques’ improvements, a thoracoscopic or laparoscopic approach has also been proposed. The use of a thoracic or abdominal surgical approach depends on the surgeon’s familiarity, with general surgeons decide for laparotomy, while thoracic ones for a thoracotomy (13,34,35).

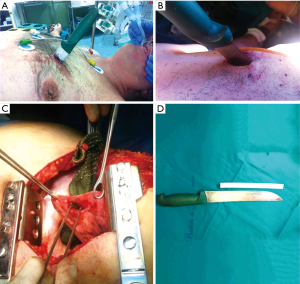

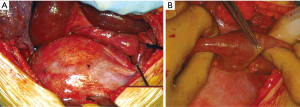

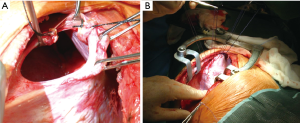

We, as other authors (36), are in favour with the thoracotomic approach. A classic 7th or 8th intercostal thoracotomy provides, in fact, an optimal visualization of the diaphragm and a correct access to it. Through this approach it is very easy to discover the diaphragmatic rupture, free the herniated abdominal organs from possible adhesions with the lung or the chest wall, properly reduce them in abdomen, treat the diaphragmatic laceration with a permanent direct suture. Through a thoracotomy is also possible to treat any obstructive organ complications, such as necrosis or perforation (Figure 1).

Furthermore, when this procedure is complicated, it is possible to enlarge the diaphragmatic laceration, allowing a better viscera reduction into the abdomen (Figure 9).

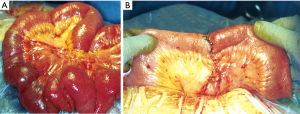

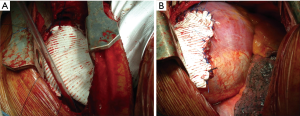

A direct tension-free primary closure of the diaphragmatic defect (Figure 10) is usually attempted, especially in case of small hernias. Interrupted 0 Vicryl mattress suture, placed under direct visualization is commonly used (34,35,37). Prosthesis (Mersilene, Prolene, Duo-mesh patches) may be employed in case of very large diaphragmatic defects, or when a direct tension-free suture is not deemed feasible. A second lower thoracotomy, using the same skin incision (Figure 11A,B) is seldom needed to achieve the best prosthesis adaptation to the diaphragmatic defect.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Sennertus RC. Diaphragmatic hernia produced by a penetrating wound. Edinburgh Med Surg J 1840;53:104.

- Carter BN, Giuseffi J, Felson B. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther 1951;65:56-72. [PubMed]

- Epstein LI, Lempke RE. Rupture of the right hemidiaphragm due to blunt trauma. J Trauma 1968;8:19-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim BL, Teo LT, Chiu MT, et al. Traumatic diaphragmatic injuries: a retrospective review of a 12-year experience at a tertiary trauma centre. Singapore Med J 2017;58:595-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmed N, Jones D. Video-assisted thoracic surgery: state of the art in trauma care. Injury 2004;35:479-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray JA, Demetriades D, Cornwell EE 3rd, et al. Penetrating left thoracoabdominal trauma: the incidence and clinical presentation of diaphragm injuries. J Trauma 1997;43:624-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Murray JA, Berne J, Asensio JA. Penetrating thoracoabdominal trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1998;16:107-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rubikas R. Diaphragmatic injuries. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:53-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de la Rocha AG, Creel RJ, Mulligan GW, et al. Diaphragmatic rupture due to blunt abdominal trauma. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1982;154:175-80. [PubMed]

- Lee WC, Chen RJ, Fang JF, et al. Rupture of the diaphragm after blunt trauma. Eur J Surg 1994;160:479-83. [PubMed]

- Sharma OP. Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture: not an uncommon entity--personal experience with collective review of the 1980's. J Trauma 1989;29:678-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schwindt WD, Gale JW. Late recognition and treatment of traumatic diaphragmatic hernias. Arch Surg 1967;94:330-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Athanassiadi K, Kalavrouziotis G, Athanassiou M, et al. Blunt diaphragmatic rupture. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;15:469-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gwely NN. Outcome of blunt diaphragmatic rupture. Analysis of 44 cases. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2010;18:240-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Miller L, Bennett EV Jr, Root HD, et al. Management of penetrating and blunt diaphragmatic injury. J Trauma 1984;24:403-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ozpolat B, Kaya O, Yazkan R, et al. Diaphragmatic injuries: a surgical challenge. Report of forty-one cases. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;57:358-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Testini M, Girardi A, Isernia RM, et al. Emergency surgery due to diaphragmatic hernia: case series and review. World J Emerg Surg 2017 18;12:23.

- Davoodabadi A, Fakharian E, Mohammadzadeh M, et al. Blunt traumatic hernia of diaphragm with late presentation. Arch Trauma Res 2012;1:89-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kearney PA, Rouhana SW, Burney RE. Blunt rupture of the diaphragm: mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment. Ann Emerg Med 1989;18:1326-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ward RE, Flynn TC, Clark WP. Diaphragmatic disruption secondary to blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma 1981;21:35-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reber PU, Schmied B, Seiler CA, et al. Missed diaphragmatic injuries and their long-term sequelae. J Trauma 1998;44:183-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp G, Khalfallah A, Girard R, et al. Blunt diaphragmatic rupture. Am J Surg 1984;148:292-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Meyers BF, McCabe CJ. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Occult marker of serious injury. Ann Surg 1993;218:783-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergeron E, Clas D, Ratte S, et al. Impact of deferred treatment of blunt diaphragmatic rupture: a 15-year experience in six trauma centers in Quebec. J Trauma 2002;52:633-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kanowitz A, Marx JA. Delayed traumatic diaphragmatic hernia simulating acute tension pneumothorax. J Emerg Med 1989;7:619-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hahn DM, Watson DC. Tension hydropneumothorax as delayed presentation of traumatic rupture of the diaphragm. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1990;4:626-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seelig MH, Klingler PJ, Schönleben K. Tension fecopneumothorax due to colonic perforation in a diaphragmatic hernia. Chest 1999;115:288-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bergin D, Ennis R, Keogh C, et al. The "dependent viscera" sign in CT diagnosis of blunt traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;177:1137-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nchimi A, Szapiro D, Ghaye B, et al. Helical CT of blunt diaphragmatic rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;184:24-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Desir A, Ghaye B. CT of blunt diaphragmatic rupture. Radiographics 2012;32:477-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen HW, Wong YC, Wang LJ, et al. Computed tomography in left-sided and right-sided blunt diaphragmatic rupture: experience with 43 patients. Clin Radiol 2010;65:206-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, White CS, et al. MR imaging evaluation of hemidiaphragms in acute blunt trauma: experience with 16 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;167:397-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mirvis SE, Shanmuganagthan K. Imaging hemidiaphragmatic injury. Eur Radiol 2007;17:1411-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haciibrahimoglu G, Solak O, Olcmen A, et al. Management of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Surg Today 2004;34:111-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Esme H, Solak O, Sahin DA, et al. Blunt and penetrating traumatic ruptures of the diaphragm. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;54:324-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blitz M, Louie BE. Chronic traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Thorac Surg Clin 2009;19:491-500. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mihos P, Potaris K, Gakidis J, et al. Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm: experience with 65 patients. Injury 2003;34:169-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]