A quality assessment of evidence-based guidelines for the prevention and management of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review

Introduction

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is the most common type of hospital-acquired infection with a high incidence (2.5–40%) and mortality (13–25.2%), which increase in patients with a multi-drug resistant or pan-drug resistant pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii, or methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (1,2). Patients with VAP require long hospitalization times and incur high costs of hospitalization (3-5). In China, the incidence and mortality of VAP are 4.7–55.8% and 19.4–51.6%, respectively, significantly higher than in Western countries (3,6). The prevention and management of VAP remains a major challenge to clinicians, despite advances in critical medicine care, improved mechanical ventilation, and the widespread use of antibacterial drugs (1). Evidence-based guidelines (EBGs) for VAP are needed for the best clinical decision (7,8).

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) instrument is an internationally recognized and reliable method of assessing guidelines (9-11). We believe that it is necessary to conduct a systematic literature search to identify existing EBGs pertaining to VAP, as well as evaluate these guidelines’ methodological quality and differences in EBGs obtained from different sources.

Methods

Literature search

A literature search was conducted in the PubMed, Excerpt Medical Database (EMbase), Web of Science, Cochrane Library, WANFANG database, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), VIP information, Chinese Biomedical Literature database (CBM), U.S National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC), Guidelines-International Network (G-I-N), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG), National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP), European Respiratory Society (ERS), and British Thoracic Society (BTS) to identify EBGs for VAP. The search strategy used combinations of the following key words: “ventilator-associated pneumonia”, “VAP”, “hospital acquired pneumonia”, “HAP”, “nosocomial pneumonia”, “guideline”, “guidance”, “guide”, “recommendation”, “consensus”, “suggestion”, “strategy” and “strategies”. The search results were limited to guidelines focusing on the prevention and/or management in adults or children with VAP and with the publication dates from database inception to July 2018.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) EBGs—this refers to a guideline providing clear evidence-supported recommendations for clinical practice that includes the strength of recommendation or level of evidence identified by a systematic search and assessment of current evidence; (II) VAP; (III) interventions for the prevention and/or management of VAP; (IV) Chinese or English publications.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) old versions or duplication of guidelines; (II) translated or adapted versions of guidelines from other countries; (III) systematic reviews or interpretations of guidelines; (IV) clinical trials; (V) guidelines published in books, booklets, or government documents; (VII) publications not in Chinese or English.

Guidelines selection and data extraction

Two pairs of reviewers (K Wan and G Yan) and (B Zou and C Huang) independently assessed the title and abstracts of publications found using the search criteria. Full-text manuscripts were reviewed when these suggested the publication met inclusion criteria. Studies included from a reference and citation analysis were also assessed.

The two pairs of reviewers extracted general characteristics of the included EBGs. The following descriptive information was extracted from each guideline: year of publication, version, country of guideline development, institution or organization responsible for guideline development, target population, number of references, recommendations for prevention and/or management, strength of recommendation, level of evidence, and size of the document. A cross-check of the assessment results and descriptive information was performed. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by consulting a third expert (M Jiang).

Quality assessment

The AGREE II instrument is the most highly validated and had the most extensive coverage over domains to assess the methodological quality of guidelines (12). This standard is widely recognized for its utility by international organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO). The instrument contains 23 specific items divided into six domains, followed by two overall items (11). The six domains are: scope and purpose (3 items), stakeholder involvement (3 items), rigor of development (8 items), clarity and presentation (3 items), applicability (4 items) and editorial independence (2 items). Each item is scored using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), based on examples and instructions described in the AGREE II manual (11). The standardized score for the individual domain ranges from 0% to 100%. This score is calculated using the formula: (obtained score – minimal possible score)/(maximal possible score – minimal possible score) × 100% (11).

The final overall guideline recommendation considered all domain items (9). The AGREE II manual (11) does not provide guidance for rating the overall quality for each guideline and evaluating the final recommendation for use. Considering the importance and significance of these two domains, we assigned double weight to rigor of development and applicability (9,13). A guideline was “recommended” if overall scores were above 60%, “recommended with modifications” if scores were between 30% and 60%, and “not recommended” if scores were below 30% (9). All reviewers were trained in AGREE II scoring to ensure that each individual’s understanding of each item was basically the same. Four well-trained reviewers (Drs. K Wan, G Yan, B Zou, and C Huang) assessed the guidelines independently using the AGREE II instrument.

Statistical analysis

The overall assessment of conformity between reviewers across each domain was calculated using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) with 95% CIs (14). ICC that was 0.75 or higher was interpreted as excellent reliability, 0.40 to 0.75 as moderate reliability and less than 0.40 as poor reliability (15-17). Descriptive and statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corporation). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant (18).

Results

Study selection and guidelines characteristics

A comprehensive search of databases and websites identified 2,081 studies. A total of 591 were duplicate studies and 1,377 more were excluded after screening titles and abstracts. The remaining 113 studies were screened by full text analysis. One hundred of these were excluded using study criteria. Thirteen unique EBGs were identified for evaluation (1,3,19-29) (Figure 1 and Table 1). All guidelines were published from 2004 to 2018. Four (30.8%) were developed in Canada, two (15.4%) in the USA, two (15.4%) in China, and the rest in Japan, South Africa, India, United Kingdom and combinations of multiple countries. Three (23.1%) guidelines focused on treatment of disease, three (23.1%) on prevention, and the rest on both. Nine (69.2%) guidelines provided recommendations for adults with VAP, one (7.7%) for children, and two (15.4%) for both. Only three (23.1%) guidelines defined the specific age of patients they were meant for. Twelve (92.3%) guidelines were developed by medical societies or associations.

Full table

Quality assessment of guidelines

Overall agreement between reviewers was considered excellent (ICC, 0.885; 95% CI, 0.862–0.905).

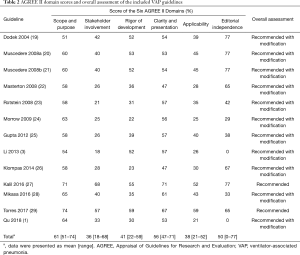

Standardized AGREE II domain scores and overall assessment of the 13 guidelines are summarized in Table 2. The mean overall score for all included guidelines was moderate (mean ± SD, 45%±10%; range, 31–63%). The scope and purpose domain received the highest domain score (mean, 61%; range, 51–74%). Clarity of presentation had the second highest score (mean, 56%; range, 47–71%), and two (15.4%) domains had scores of less than 50%. Editorial independence had domain scores that varied widely among the guidelines (SD, 28%; range, 0–77%); the mean score was 50%. Two guidelines (15.4%) developed in China did not include information defining sponsorship information or conflicts of interest among development members. Guidelines scored relatively low in the rigor of development and applicability domains with a mean of 41% and 38%, respectively. Only seven (53.8%) guidelines detailed the search strategies used to obtain clinical evidence and six (46.2%) described methods to be used to update the guidelines in the future. Three (23.1%) guidelines analyzed obstacles identified in applying the guidelines. The stakeholder involvement domain received the lowest mean score with a mean of 36%. Six (46.2%) guidelines had a score less than 30% in this domain. No guideline stated that patients or the general public were included in the development group.

Full table

Among the 13 including EBGs, two (15.4%) were “recommended” for clinical practice, achieving high overall scores above 60%, and the remaining (84.6%) were “recommended with modifications”, scoring of 30–60% (Table 2). No guidelines were “not recommended”.

Grading systems used to develop evidence and recommendations for guidelines

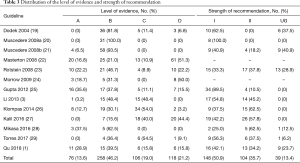

Guideline developers used different systems assess the evidence presented in the different EBGs pertaining to VAP (Table 1). Six (46.2%) of the 13 guidelines used the Grades of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, four (30.8%) used the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination (CTHPHC) system, one (7.7%) used the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) system, and two (15.4%) used a self-formulated system. We developed a new system based on the GRADE approach (see Table S1) (13,30). In this new system we re-classified the levels of evidence and the strength of recommendations of included EBGs.

Full table

The distribution of the level of evidence and strength of recommendations of evaluated EBGs is listed in Table 3. A total of 558 articles were used as evidence in the 13 EBGs. Seventy-six evidence (13.6%) were classified as level A, 258 (46.2%) as level B, 106 (19.0%) as level C, and 118 (21.2%) as level D. The guideline by Mikasa 2016 (28) had the highest proportion of level A evidence (37.5%), followed by that of Gupta 2012 (25) with 35.6%. Among the 291 recommendations, 148 (50.9%) were rated as strong (grade I), 104 (35.7%) as weak (grade II), and 39 (13.4%) as ungraded (UG). All the recommendations provided by Muscedere 2008a (20) were grade I. Two guidelines (22,24) did not grade the recommendations.

Full table

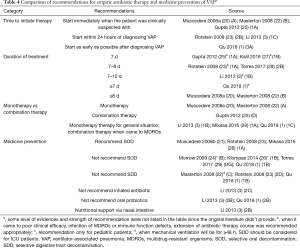

Recommendations for prevention and management

Six guidelines (1,3,20,22,23,25) (46.2%) recommended that empiric (preventive) antibiotic therapy be administered as early as possible, and four (1,25,27,28) (30.8%) recommended that therapy be developed according to local microbiological flora and resistance profiles (Table 4). Most guidelines recommend that VAP patients receive an approximately seven-day course of empiric antibiotic therapy. Some guidelines (1,3,25,27,28) recommended a dose de-escalating strategy of antibiotic administration based on different specific situations in order to avoid bacterial resistance. The choice of antibiotics recommended for monotherapy and combination therapy varied among guidelines.

Full table

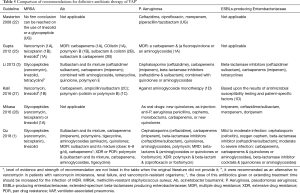

Recommendations for definitive antibiotic therapy in the VAP guidelines are presented in Table 5. Six guidelines (46.2%) provided specific recommendations for the treatment of different VAP pathogens. The recommendations of the different guidelines were basically the same for definitive antibiotic therapy. The overall assessment for VAP treatment was that antibiotic treatment regimens be altered according to the pathogen of infection and its susceptibility (1). The timing and schedule of therapy should be adjusted as clinically indicated, which helps reduce unnecessary side effects to improve the clinical outcomes.

Full table

There were several recommendations for adjunctive treatments in patients with VAP. One guideline (1) recommended the use of glucocorticoids for patients with severe VAP and hemodynamic instability. Glucocorticoids were not recommended for routine use in three guidelines (1,3,22). Enteral nutrition and immunotherapeutic use were recommended on an individual basis (1). Besides, the use of selective oral decontamination (SOD) was not routinely recommended for the prevention of VAP (Table 4). Selective digestive tract decontamination (SDD) (1,3,22,23), nebulized endotracheal antibiotics (3), and oral probiotics (1,3) were also not recommended for routine use. The comparison of recommendations in two recommended guidelines is presented in Table S2.

Full table

Discussion

EBGs are essential target-based summaries of medical care, whose quality determines the outcomes of clinical application (31). Recently, an increasing number of EBGs pertaining to VAP were developed. Ambaras Khan et al. (32) had evaluated the quality of six guidelines, and only two provided specific recommendations for empirical antibiotics and antibiotic de-escalation therapy for VAP. Unfortunately, the EBGs used for VAP were far from complete; in addition, the overall quality of the two EBGs and the levels of evidence used to make them were unclear. Thus, we re-evaluated the 13 identified EBGs pertaining to VAP, and variability in the methodology and quality of these EBGs was found in this study.

Based on the analysis of the AGREE II quality score, the highest-scoring domain was found with the scope and purpose followed by clarity of presentation domains (Table 2), which indicated that most guidelines fully satisfied these criteria. Most guidelines could fully describe the overall objective, target population and their specific clinical issues (33). Guidelines with well adherence to these key information appeared to be more easily accepted and accessed by its intended users (34). What’s more, adhering to the aspects of these domains does not require a great deal of human power, financial and material resources.

The potential for improvements is needed in several domains. Stakeholder involvement had the lowest score among AGREE II domains. Implementation of guidelines requires contribution and expertise of multidisciplinary medical team (including clinical experts, methodological experts, health economists, etc.), coupled with the target population’ values and preference of healthcare, so as to ensure that recommendations are advisable, unbiased, and reliable (35,36). However, only two (15.4%) guidelines provided details regarding involvement of patients or the public, and seven (53.8%) included these experts in the guidelines we reviewed. Owing to limited information regarding relevant tools for their application and possible barriers, applicability scored disturbingly low. This indicated that guideline developers may not understand the value and importance of the components of the domain and items (including the implementation of pilot testing, economic assessment, educational tools and patient leaflets, etc.). Most notably, the guidelines lacking clinical applicability were a complete waste of money and time. Rigor of development was considered the most crucial domain in the assessment of guideline development. This domain evaluated the methods used in guideline development, including the methods used to search the literature, identify evidence, evaluate the quality of the evidence, and how recommendations were derived (35-37). Reporting all methodological aspects is therefore particularly essential to allow the intended guideline users to judge the validity of the content. Nevertheless, none of the guidelines scored above 60% in this domain, and only seven (53.8%) guidelines reported the methods used to perform the systematic literature search.

The grading system used for evaluating the level of evidence and strength of recommendation varied among different guidelines, which might lead to confusion among the guideline users as to how they are used in clinical practice (38,39). There is a need for a standardized grading system. Although the majority of recommendations were classified as grade I, many were derived from low- or poor-quality evidence. This could be due to an inadequate literature search strategy that did not identify high-quality evidence or that such evidence does not indeed exist. Improved methods to search the literature and identify best evidence supporting the recommendation will have the largest impact on this point. Besides, an increasing number of clinical research centers, which allows for greater coordination of studies and increases the investment in research funding, greatly contributes to the development of more high-quality evidence.

An important level of consensus appears for the recommendations throughout the various EBGs. However, there are some conflicts mainly in the drug choice and adjustment of empirical and targeted antibiotic therapies, which plays an important role in the management of VAP (1). There are four main reasons contributing to the variances: (I) developers are inclined to develop guidelines based on local conditions and indigenized evidence, such as differences in the variance of pathogens and its drug resistance; (II) owing to the different publication time of EBGs, the timely updated evidence could lead to the changes of recommendations; (III) recommendations may be constructed on the opinions of personal experts but not the trustworthy consensus statements because of the scant or imperfect evidence; (IV) the expectation and preference of the public or patients may influence the ultimate recommendations in EBGs. Thus, a local and updated guideline could provide more useful and reliable information for clinicians.

We made the following recommendations to improve the quality of guidelines. First, the methodological quality should be stringently scrutinized and censored, and randomized trials should be conducted before widespread implementation of guidelines. Second, guidelines should also be periodically reassessed and updated in a timely manner to improve the quality of guidelines. Third, more high-quality further studies are needed to strengthen the evidence and resolve controversy of guidelines. Fourth, consensus on a standardized grading system for the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations must be reached. Furthermore, strengthen the international collaboration to make regulations to develop a guideline framework on guideline development and improve the quality of the guidelines.

Limitations and strengths

Our study has several strengths. A comprehensive and systematic search of the literature was performed and agreement regarding the findings was achieved between two review teams. The AGREE II instrument was used to test guideline assessment and the methodological quality of EBGs.

Limitations included a literature search of only English and Chinese publications. The AGREE II instrument focuses on assessing the methods of guideline development and transparency of reporting. It does not assess the potential impact of recommendations on patient outcomes. The minimal reporting of how the guidelines were derived varied may have contributed to lower assessment scores.

Conclusions

The overall quality of VAP EBGs was moderate. Significant shortcomings, particularly in the stakeholder involvement, rigor of development and applicability domains, were observed. The grading system used to evaluate levels of evidence and strength of recommendation should be unified in future guidelines. The category, methods of use, and course of antibiotics administered to prevent or manage VAP varied by guideline. More high-quality evidence is needed to improve guideline recommendations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Accdon (www.Accdon.com) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Educational Scientific Planning Project of Guangzhou Medical University in 2016, the Ninth Educational Scientific Reform Research Project of Guangzhou Higher Education Institutions (2017E07), and the College Students’ Science and Technology Innovation Project of Guangzhou Medical University in 2018-2019 (2017A014).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Chinese Thoracic Society Infection Group. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hospitals-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults in China. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases 2018;41:255-80.

- Kollef MH, Hamilton CW, Ernst FR. Economic impact of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a large matched cohort. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2012;33:250-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chinese Society of Critical Care Medicine. Guidelines for for the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chinese Journal of Internal Medicine 2013;52:524-43.

- Restrepo MI, Anzueto A, Arroliga AC, et al. Economic burden of ventilator-associated pneumonia based on total resource utilization. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010;31:509-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muscedere JG, Day A, Heyland DK. Mortality, attributable mortality, and clinical events as end points for clinical trials of ventilator-associated pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51 Suppl 1:S120-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xie DS, Xiong W, Lai RP, et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care units in Hubei Province, China: a multicentre prospective cohort survey. J Hosp Infect 2011;78:284-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yaşar I, Kahveci R, Artantaş AB, et al. Quality Assessment of Clinical Practice Guidelines Developed by Professional Societies in Turkey. PLoS One 2016;11:e0156483. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sekercioglu N, Al-Khalifah R, Ewusie JE, et al. A critical appraisal of chronic kidney disease mineral and bone disorders clinical practice guidelines using the AGREE II instrument. International Urology & Nephrology 2017;49:273-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiang M, Liao LY, Liu XQ, et al. Quality Assessment of Clinical Practice Guidelines for Respiratory Diseases in China: A Systematic Appraisal. Chest 2015;148:759-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Middleton JC, Kalogeropoulos C, Middleton JA, et al. Assessing the methodological quality of the Canadian Psychiatric Association's anxiety and depression clinical practice guidelines. J Eval Clin Pract 2019;25:613-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010;182:E839-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burls A. AGREE II-improving the quality of clinical care. Lancet 2010;376:1128-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jiang M, Guan WJ, Fang ZF, et al. A Critical Review of the Quality of Cough Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2016;150:777-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979;86:420-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uzeloto JS, Moseley AM, Elkins MR, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines for chronic respiratory diseases and the reliability of the AGREE II: an observational study. Physiotherapy 2017;103:439. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Appenteng R, Nelp T, Abdelgadir J, et al. A systematic review and quality analysis of pediatric traumatic brain injury clinical practice guidelines. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201550. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fleiss JL. The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1986.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dodek P, Keenan S, Cook D, et al. Evidence-based clinical practice guideline for the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:305-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muscedere J, Dodek P, Keenan S, et al. Comprehensive evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for ventilator-associated pneumonia: diagnosis and treatment. J Crit Care 2008;23:138-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muscedere J, Dodek P, Keenan S, et al. Comprehensive evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for ventilator-associated pneumonia: prevention. J Crit Care 2008;23:126-37. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masterton RG, Galloway A, French G, et al. Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia in the UK: report of the working party on hospital-acquired pneumonia of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;62:5-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rotstein C, Evans G, Born A, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2008;19:19-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrow BM, Argent AC, Jeena PM, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of paediatric ventilator-associated pneumonia. S Afr Med J 2009;99:255-67. [PubMed]

- Gupta D, Agarwal R, Aggarwal AN, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia in adults: Joint ICS/NCCP(I) recommendations. Lung India 2012;29:S27-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klompas M, Branson R, Eichenwald EC, et al. Strategies to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2014;35:915-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kalil AC, Metersky ML, Klompas M, et al. Management of Adults With Hospital-acquired and Ventilator-associated Pneumonia: 2016 Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Thoracic Society. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:e61-111. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mikasa K, Aoki N, Aoki Y, et al. JAID/JSC Guidelines for the Treatment of Respiratory Infectious Diseases: The Japanese Association for Infectious Diseases/Japanese Society of Chemotherapy - The JAID/JSC Guide to Clinical Management of Infectious Disease/Guideline-preparing Committee Respiratory Infectious Disease WG. J Infect Chemother 2016;22:S1-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Torres A, Niederman MS, Chastre J, et al. International ERS/ESICM/ESCMID/ALAT guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: Guidelines for the management of hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)/ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) of the European Respiratory Society (ERS), European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM), European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and Asociacion Latinoamericana del Torax (ALAT). Eur Respir J 2017. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatology International 2016;10:1-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lim W, Arnold DM, Bachanova V, et al. Evidence-based guidelines--an introduction. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2008.26-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ambaras Khan R, Aziz Z. The methodological quality of guidelines for hospital-acquired pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia: A systematic review. J Clin Pharm Ther 2018;43:450-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhatt M, Nahari A, Wang PW, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines for management of pediatric type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review using the AGREE II instrument. Syst Rev 2018;7:193. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu J, Chen R, Wu S, et al. The quality of clinical practice guidelines in China: a systematic assessment. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:961-7. [PubMed]

- Li Q, Yang Y, Pan Y, et al. The quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines for intracranial aneurysms: a systematic appraisal. Neurosurg Rev 2018;41:629-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in healthcare. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1308-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Acuña-Izcaray A, Sánchezangarita E, Plaza V, et al. Quality assessment of asthma clinical practice guidelines: a systematic appraisal. Chest 2013;144:390-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fang Y, Yao L, Sun J, et al. Appraisal of clinical practice guidelines on the management of hypothyroidism in pregnancy using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II instrument. Endocrine 2018;60:4-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]