Catamenial pneumothorax

Definition of catamenial pneumothorax (CP)

CP is defined as spontaneous recurrent pneumothorax, occurring in women of reproductive age, in temporal relationship with menses (1-21).

The relationship of CP with significant lung disease (including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute asthma, and bullous disease) has not been investigated, but pneumothoraces considered secondary to a known underlying lung disease has not been classified as catamenial (3,5,20). Nevertheless, co-existence of CP and a known underlying lung disease cannot be excluded. Co-existence of cystic fibrosis and endometriosis-related CP and haemoptysis has been reported in a patient (22).

At least one recurrence is required (at least two episodes of pneumothorax in total) to fulfill the definition criteria. Nevertheless, the mean number of recurrences of surgically treated patients is usually higher (3,11,12,20).

CP is a syndrome generally considered to occur in ovulating women, while women during pregnancy, menarche and on ovulatory suppressants (such as contraceptive medication) are generally not considered subject to it (23). Nevertheless, there are rare case reports of “CP” in women on ovulatory suppression (23) and during pregnancy (24).

Temporal relationship of CP with menses

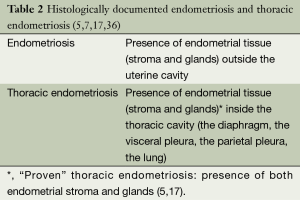

The word “catamenial” is derived from the Greek word “katamenios” meaning monthly occurrence. The CP has been described as “correlated”, “timed”, and “associated” with, “corresponding to” “accompanied by” “in association with” “in synchrony with” menses or menstruation or the menstrual cycle (11-13,16,17,24,25). It has also been described as occurring “simultaneously with the menstruation” (26), “in the few hours after menstruation” (27), “during menstruation” (18), “only at the time of menstrual flow” (28), but also “during or preceding” (10,11), “during or following” (17) menstruation, “at or around the onset of menses” (29), and “close to menstrual periods” (14). Some authors defined the exact temporal relationship of CP with menses (1,3-5,8,13-15,17,27). The wider time periods defined were 72 hours before or after the onset of menstruation (14,15) or “within 5 to 7 days of menses” (1) (Table 1).

Full table

Laterality of CP

In the vast majority of CP cases (87.5-100%) the right side is involved (5,12,13,15,17,19,20,24,26,27), but CP can be left sided (30) or bilateral (31,32).

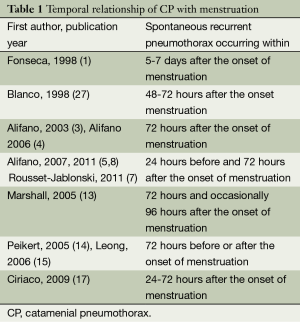

Endometriosis, thoracic endometriosis, thoracic endometriosis syndrome

CP is associated with thoracic and pelvic endometriosis, although endometriosis is not universally documented (1-9,11-18,20,23,30,31,33-35). Endometriosis is defined as the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue (stroma and glands) outside the uterine cavity (Table 2). It is considered an enigmatic disease of unclear aetiology and difficult management. The most common form is pelvic endometriosis, usually manifested with pelvic pain (mid-cycle pain, dysmenorrhoea, dyspareunia) and infertility (36). Thoracic endometriosis is defined as the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue into the thoracic cavity, which is the most frequent extra-pelvic location of endometriosis (35). Thoracic endometriosis has been considered as histologically “proven” after identification of endometrial stroma and glands in the thoracic lesion(s) (5,7,17,20,36), and as “probable” after identification of stroma only (5) (Table 2).

“Probable” thoracic endometriosis: presence of endometrial stroma only (5), pathologic criteria for thoracic endometriosis: presence of both endometrial stroma and glands, or stroma only staining positively with estrogen/progesterone receptors (7). Thoracic endometriosis affects the right hemithorax in 85-90% of cases (33,34).

Spontaneous pneumothorax is the most common clinical manifestation of thoracic endometriosis (5,37), occurring in 72-73% of patients (33,34), followed by catamenial haemoptysis, catamenial haemothorax and endometriotic thoracic nodules (34). The mean age at presentation of thoracic endometriosis is 34-35 years (33,34,37). Catamenial haemoptysis occurs at a younger mean age than CP (33). Joseph et al. [1996] (33) used the term “thoracic endometriosis syndrome” to include the clinical manifestations of thoracic endometriosis, mainly CP, haemoptysis, haemothorax, and lung nodules, but also catamenial chest pain and pneumomediastinum. Thoracic endometriosis has been revealed in a significant percentage of ovulating women referred for surgical treatment of recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax, being mainly related with catamenial, but also with non CP (7,20). In a recent retrospective study of a referral center by Rousset-Jablonski et al. (7), among 156 premenopausal women who were surgically treated for spontaneous pneumothorax, histologically documented thoracic endometriosis was found in 23.1% (36/156) of all patients (including catamenial and non CP patients), being 6.5 times more frequent in patients with catamenial than in patients with non CP. Pelvic endometriosis was found in about 50% of cases of thoracic endometriosis, with wide variation among studies (11-13,26,27). In the analysis of 110 thoracic endometriosis cases by Joseph et al. [1996], pelvic endometriosis was found in 84% (51/61) of investigated patients with thoracic endometriosis (33). There was a significant relationship between pelvic and thoracic endometriosis, with a peak incidence of thoracic endometriosis occurring about 5 years later than the peak incidence of pelvic endometriosis (33,37). Catamenial haemoptysis was most often associated with pelvic endometriosis compared with other manifestations of thoracic endometriosis (including CP) (33).

Thoracic and pelvic endometriosis in patients with CP

Although CP is the most frequent clinical manifestation of thoracic endometriosis, clinical, macroscopic and furthermore histological evidence of thoracic endometriosis has not been revealed in all cases of CP (3-5,7,8,12-14,17,20,33,34). According to the review by Korom et al. (12), thoracic endometriosis was found in 52.1% (73/140) of surgically treated patients with CP (for whom description of the lesions was available).

According to Alifano (6), histological evidence of thoracic endometriosis can be found in most CP patients undergoing surgery. Histologically confirmed thoracic endometriosis was revealed in 87.5% (7/8) and in 64.86% (24/37) of surgically treated CP patients included in the prospective and retrospective studies (respectively) of a referral centre (3,7). CP has been associated with clinically and/or histologically diagnosed pelvic endometriosis in 20-70% of CP cases (7,11-13,17,33,37). The wide variation may be explained by the diversity of the investigation for it.

Thoracic endometriosis in patients with non CP

Thus, thoracic endometriosis can be found in most, but not all cases of CP. Furthermore, there are cases of non-CP (occurring in the intermenstrual period) that are associated with thoracic endometriosis (5,7,20,24). As endometriosis-related pneumothorax can be defined spontaneous pneumothorax associated with findings of thoracic endometriosis. The presence of catamenial character (although common) is not required. In the recent retrospective study of a referral center by Rousset-Jablonski et al. (7) among 156 premenopausal women who were surgically treated for spontaneous pneumothorax, histologically confirmed thoracic endometriosis was found in 10% (12/119) of women with non CP.

Catamenial and/or endometriosis related pneumothorax

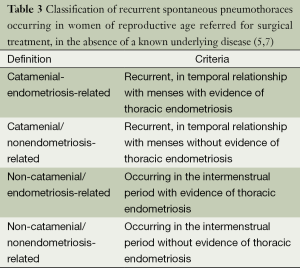

Thus, the CP (occurring in temporal relationship with menses) can be thoracic endometriosis-related or non endometriosis-related (5,7,20,24). Similarly, the non-CP (occurring in the intermenstrual period) can be endometriosis-related or nonendometriosis-related (5,7,20,24).

Finally, endometriosis-related pneumothoraces can be catamenial or non-catamenial (5,7,20,24) (Table 3).

Full table

Pneumothoraces with catamenial character (with or without evidence of thoracic endometriosis) as well as pneumothoracies with evidence of thoracic endometriosis (with or without catamenial character) can be classified under the term catamenial and/or endometriosis related pneumothorax (including the first three categories of Table 3).

Despite the definitions, it seems that in the literature pneumothoracies are diagnosed as “catamenial” without strict relationship with menses [even when occurring during pregnancy (24)], and as “endometriosis-related” without histologic evidence of endometrial glands or even stroma, based on clinical and macroscopic surgical findings (20,21,38,39).

Incidence of catamenial and/or endometriosis related pneumothorax

CP was generally considered a rare entity, with an incidence of less than 3-6% among women suffering of spontaneous pneumothorax. Decreased disease awareness and underdiagnosis may have accounted for it (3,5,6,10-13,15,17,20,23,27,40,41).

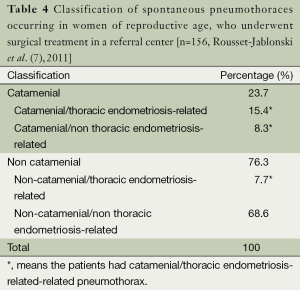

Nevertheless, the incidence of catamenial and/or endometriosis related pneumothorax was much higher among women of reproductive age referred for surgical treatment of recurrent spontaneous pneumothoraces, fluctuating between 18% and 33% (5-7,13,17).

In the recent retrospective study of a referral center by Rousset-Jablonski et al. (7), among 156 premenopausal women who were surgically treated for spontaneous pneumothorax, 31.4% (49/156) could be classified as catamenial and/or thoracic endometriosis related pneumothorax (Table 4).

Full table

CP was defined as recurrent (at least two episodes in total), spontaneous pneumothorax occurring in women of reproductive age with 24 hours before and 72 hours after the onset of menses (7).

The diagnosis of thoracic endometriosis was made after histologic documentation of both endometrial stroma and glands in thoracic lesion(s) or histologic documentation of stroma only staining positively with estrogen/progesterone receptors (7).

The presence of catamenial character and/or thoracic endometriosis among women with recurrent spontaneous pneumothoraces has been underdiagnosed. Previously unidentified thoracic endometriosis was revealed at re-operation in patients with recurrent pneumothoraces after unsuccessful thoracoscopic or open procedures (8,12,20). In a retrospective study by Alifano et al. (8), among 35 women of reproductive age that underwent reoperation for recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax, evidence of thoracic endometriosis was revealed only at reoperation in 13 patients (37%). In those patients the initial diagnoses were catamenial non endometriosis-related pneumothorax (eight cases) and “idiopathic” pneumothorax (four cases). Underdiagnosis of thoracic endometriosis can be attributed to decreased disease awareness, incomplete search for the lesions, but also to the catamenial and long term variations in the size, appearance and number of the lesions (20).

Aetiopathogenetic theories of catamenial and/or endometriosis related pneumothorax

The aetiopathology of catamenial and/or endometriosis-related pneumothorax remains obscure, although various theories have been suggested to explain it.

According to the “physiologic hypothesis” vasoconstriction and bronchospasm, caused by high levels of circulating prostaglandin F2 during menses, may induce alveolar rupture, and pneumothorax. Pre-existing bullae and/or blebs may be more susceptible to rupture during menstrual hormonal changes. Absence of characteristic lesions in a significant number of patients supports the “physiologic” theory (3,11,12,15,20,31).

According to the “metastatic or lymphovascular microembolization theory”, metastatic spread of endometrial tissue through the venous or the lymphatic system to the lungs, and subsequent catamenial necrosis of endometrial parenchymal foci that are in proximity to the visceral pleura cause air leaks and pneumothorax. Centrally located parenchymal foci result in haemoptysis (3,9,11,12,15,20,31,33). Endometrial foci in the lung parenchyma, but also in the brain, knee, and eye support the “metastatic theory” (13).

According to the “transgenital-transdiaphragmatic passage of air theory”, atmospheric air passes from the vagina to the uterus, through the cervix (due to absence of cervical mucous during menses), subsequently to the peritoneal cavity through the fallopian tubes, and finally to the pleural space through congenital or acquired (secondary to endometriosis) diaphragmatic defect(s) (3,11,12,15,20,31).

The transgenital-transdiaphragmatic passage of air theory has been supported by rare cases of concurrent (42,43) or alternating episodes CP and pneumoperitoneum (44), and a rare radiologic finding of small diaphragmatic defects (attributed to air “bubbles” passing from the peritoneum to the thoracic cavity) associated with homolateral CP (45). Recurrences of pneumothorax after hysterectomy, fallopian tube ligation, and diaphragmatic resection with postoperative total adhesion of the lung basis to the diaphragm provide strong evidence that this theory cannot explain all the CP cases (8,12,20,32).

According to the “migration theory”, retrograde menstruation results in pelvic “seeding” of endometrial tissue and migration of it through the peritoneal flow to the subdiaphragmatic areas. Most endometrial tissue is implanted to the right hemidiaphragm, due to preferential flow of the clockwise peritoneal circulation through the right paracolic gutter to it, and the “piston” action of the liver. Subsequent catamenial necrosis of the diaphragmatic endometrial implants produces diaphragmatic perforation(s). Then endometrial tissue passes through the created diaphragmatic perforation(s) and spreads into the thoracic cavity. Implantation of ectopic endometrial tissue to the visceral pleura and subsequent catamenial necrosis, results in rupture of the underlying alveoli, and pneumothorax (3,11,12,15,20,31,33). Co-existence of red, as well as brown (sloughed) endometrial diaphragmatic implants, along with diaphragmatic perforations (46), and presence of endometrial tissue at the edges of the diaphragmatic perforations in many cases of CP (11), the presence of disrupted elastic fibers on the visceral pleura close to endometrial tissue, and the presence of endometrial tissue near bleb(s) and/or bulla(e) may illustrate successive parts of the pathologic process of the migration theory (20,30).

To explain findings of thoracic endometriosis in pneumothoraces occurring in the intermenstrual period, Yoshioka et al. (24) suggested that non-camenial endometriosis-related pneumothorax can be attributed to formation of pulmonary cysts due to pulmonary endometriosis, and later rupture of those cysts occurring unrelated to the menstrual cycle. Another explanation can be late apoptosis of visceral pleural and/or superficial parenchymal endometrial implants that undergo sloughing rather than acute necrosis (20).

Clinical manifestations and diagnosis

The typical clinical manifestation of CP involves spontaneous pneumothorax preceding or in synchrony with menses, usually presented with pain, dyspnoea and cough. Scapular and/or thoracic pain preceding or in synchrony with menses, history of previous episode(s) of spontaneous pneumothorax [with or without previous operation(s)/intervention(s)], primary or secondary infertility, history of previous uterine surgical procedure or uterine scraping, symptoms and/or diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis, and rarely history of catamenial haemoptysis or catamenial haemothorax may be present (1-20).

These symptoms and medical history should be systematically searched (7). In their presence the suspicion for catamenial and/or thoracic endometriosis-related pneumothorax should be increased, while in their absence it should not be excluded (20).

Presentation in the intermenstrual period should not exclude the diagnosis of non-catamenial endometriosis-related pneumothorax, even in the absence of symptoms and/or diagnosis of pelvic endometriosis (5,20,47).

Catamenial pneumothoraces are usually mild or moderate, but they can rarely be life-threatening (as in a case of widespread thoracic endometriosis after previous operations) (48).

The mean age of women with catamenial and/or thoracic endometriosis-related pneumothorax who undergo surgery is 34-37 years (5,7,11,12).

Catamenial and/or thoracic endometriosis-related pneumothorax can have very rare presentations. A case of catamenial pneumoperitoneum mimicking acute abdomen in a woman with multiple episodes of catamenial endometriosis-related pneumothorax (44), a few cases of co-existent pneumoperitoneum and catamenial endometriosis-related pneumothorax (42,43), and a case of spontaneous endometriosis-related diaphragmatic rupture with pneumothorax and pneumoperitoneum have been reported (21).

The diagnosis of CP depends mainly on the medical history (synchronicity with menses), while the diagnosis of endometriosis-related pneumothorax is based on careful intra-operative visual inspection and appropriate histological examination of the characteristic lesions, both of which largely rely on disease awareness, and can be easily missed (8,12,20,49).

Imaging diagnostic criteria

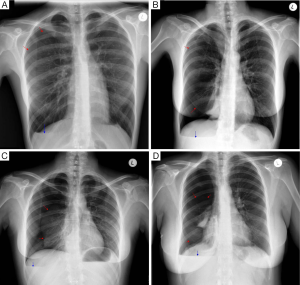

Chest radiography, less often computed tomography (CT), and rarely magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are performed. There are no specific imaging diagnostic criteria. Pneumothoraces can be of any size, usually right sided, but also left sided or bilateral. A basal air-fuid level may be present. Haemopneumothorax of various size and mediastinal shift may or may not be present (1,20) (Figure 1). In case of previous operation/intervention there may be loculation(s) (48).

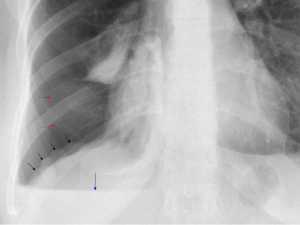

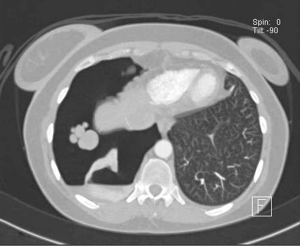

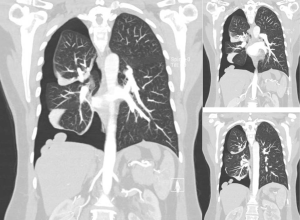

Careful inspection of the homolateral to the pneumothorax hemi-diaphragm on chest X-ray may rarely reveal small diaphragmatic defect(s), corresponding to diaphragmatic perforation(s) (45), or a round opacity on the right hemidiaphragm corresponding to liver protrusion through a large diaphragmatic defect (38). “Nodular appearance” of the right hemidiaphragm on chest X-ray and CT due to partial intrathoracic liver herniation through large confluent diaphragmatic defects (20,39) have been reported (Figures 2,3,4). A diaphragmatic mass on CT (17), and pleural masses on MRI attributed to endometriosis implants (50) have also been reported. Other rare findings include co-existing pneumothorax and pneumoperitoneum (on radiography and computed tomography) (42,43).

Cancer antigen 125

Endometriosis has been associated with increased levels of cancer antigen 125, and although it is not considered a specific marker (37), it can assist in early diagnosis of endometriosis-related pneumothorax (36).

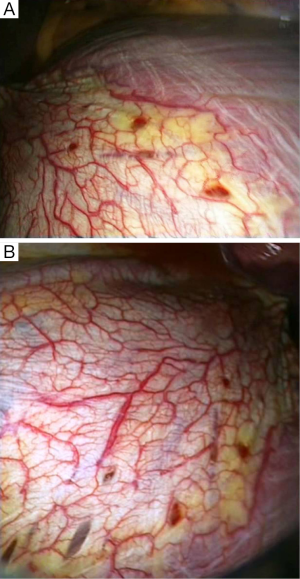

Characteristic findings associated with catamenial and/or endometriosis related pneumothorax

Characteristic lesions of the disease spectrum described by the terms catamenial and/or thoracic endometriosis-related pneumothorax include single or multiple diaphragmatic perforation(s), and/or diaphragmatic spot(s) and/or nodule(s), and/or visceral pleural spot(s) and/or nodule(s), and/or parietal pleural spot(s) and/or nodule(s), while pericardial nodules have also been described. These lesions have not been revealed in all cases of CP, while they have been found in some cases with non-CP. Endometrial tissue may or may not be found in these lesions. Endometrial tissue is usually revealed in diaphragmatic and/or pleural nodules, but it is occasionally revealed at the edges of the diaphragmatic perforations. Diaphragmatic lesions [defect(s) and/or spot(s) and/or nodule(s)] are more frequently revealed than visceral and/or parietal pleural lesion(s) [mainly spot(s) and/or nodule(s)] (1-20) (Figure 5).

Diaphragmatic defect(s)

The diaphragmatic defect(s) can be single or multiple, usually located at the central tendon, often adjacent to co-existing nodules (Figure 5). They are described as perforations, holes, fenestrations, pores, porosities, and stomata (1-20). They can be “invisible” holes proven only by diagnostic pneumoperitoneum (49), tiny holes measuring 1-3 milimeters (12,30), or larger defects measuring up to 10 mm (3,10) or more than 10 mm (15).

The proximity of the diaphragmatic defects to often co-existing spot(s) and/or nodule(s), the presence of endometrial tissue occasionally found at the edges of the defects (3,5,7,11), support the theory that the diaphragmatic defects represent cyclical breakdown of endometrial implants (11,20).

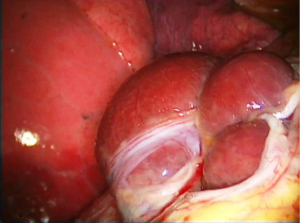

There are very rare case reports of larger laceration(s), with intrathoracic liver protrusion. Bobbio et al. (38) reported a case of CP with a 4 cm right sided diaphragmatic laceration and partial intrathoracic liver herniation. Makhija et al. (51) reported a case of CP with multiple large diaphragmatic fenestrations, of a maximum diameter of 10 cm. Pryshchepau et al. (39) reported a case of right CP with liver protrusion through a huge multi-partitioned diaphragmatic defect. In our reported series (20), we have included a case that bares characteristic similarity with these cases (Figure 6), particularly the case reported by Pryshchepau et al. (39), and we have advocated that, although rare, these findings should be included in the characteristic findings of the syndrome under the term catamenial and/or thoracic endometriosis related pneumothorax (20) (Figures 2-4,6).

Triponez et al. (21) reported spontaneous rupture of the right hemi-diaphragm, with intrathoracic liver herniation, right sided pneumothorax and pneumoperitoneum in a patient with history of premenstrual periscapular pain. A nodule resembling endometrial implant was revealed at the edge of the diaphragmatic defect. Histology of the nodule showed “hemosiderin loaded macrophages compatible with endometriosis”, without evidence of endometrial stroma or glands. They considered this case as endometriosis-related, although the histologic criteria set by their team were not met (5,7). Furthermore, the authors referring to the previously mentioned cases of large diaphragmatic defects reported by Bobbio et al. (38) and Pryshchepau et al. (39), considered them as limited diaphragmatic rupture “probably caused by endometriosis”.

Thoracic spot(s) and/or nodule(s)

The spots or nodules are considered endometrial implants, since endometrial tissue is usually found on histology. They are usually located at the diaphragm, the visceral, and/or the parietal pleura. The diaphragmatic spots or nodules are mainly found at the central tendon (often co-existing with adjacent perforations), and less frequently at the nearby muscular portion. Fonseca et al. (1) reported “pericardial implants”. The spots or nodules can be single or multiple, tiny or larger up to a few centimetres. They are described as red, purple, violet, blueberry, brown, but also black, white, greyish, and greyish-purple (1-21,52).

Variability and absence of characteristic findings

All the previous findings (diaphragmatic defects and/or thoracic spots or nodules) may coexist, or only one or more of them may be present (1-21,45,48,52,53).

These characteristic findings may be absent in cases of CP, and bleb(s) and/or bulla(e) may be the only pathological findings, while in some cases there is no identifiable thoracic pathology (11-13,17,18,20).

Macroscopic evidence of the characteristic lesions on thoracotomy or thoracoscopy depends on disease awareness and meticulous inspection of the thorax, including the diaphragm. It also depends on the stage of the disease (the size, and the number of the characteristic lesions), the catamenial and the longer term variations (11,20,49).

Surgical treatment of catamenial and/or endometriosis related pneumothorax

Surgical treatment is the treatment of choice of catamenial and/or thoracic endometriosis related pneumothorax, due to better results, regarding mainly less recurrences, in comparison to medical treatment only (1-21,33).

In 2004, Korom et al. (12) reviewing 195 cases of CP for whom adequate information was given, reported that 154 cases (78.9%) were treated surgically. Among surgically treated patients, pleurodesis (in 81.7%), diaphragmatic repair (in 38.8%), and lung wedged resection (in 20.1%) were performed.

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) has been mainly applied since 2000, being considered the treatment of choice. When extensive diaphragmatic repair is required, a video-assisted mini-thoracotomy or a muscle-sparing thoracotomy may offer better access. A conventional thoracotomy may be occasionally necessary, particularly in reoperations (3-9,11-13,15-19,30).

Apart from lung inspection for bullae, blebs, and air leaks, careful and meticulous inspection of the diaphragm (for perforations and/or spots or nodules) as well as inspection of the parietal pleura, the lung, and the pericardium (for spots and/or nodules) is of paramount importance. Bagan et al. suggested application of surgical treatment during menses, for better visualization of the endometriotic lesions (11). Slasky et al. applied diagnostic pneumoperitoneun to identify “invisible” diaphragmatic holes (49). Magnification provided by VATS may facilitate identification of the lesions (3-8,11-13,15-19). Tissue sampling for histologic documentation facilitates the diagnosis of thoracic endometriosis (6).

Alifano et al. suggested resection of all visible lesions (when technically feasible), including resection of blebs or bullae, as well as resection of endometriotic thoracic lesions, by limited wedged resection of the diseased lung area (with endostapler if possible), limited parietal pleurectomy, and partial diaphragmatic resection, to remove pulmonary, pleural, and diaphragmatic lesions (respectively) (3).

Bulla(e) and/or bleb(s) excision and/or (usually apical) wedged resection (12,13,17,20), along with pleurodesis or pleurectomy has been usually performed (12,13,15,17,19,20).

Addressing the diaphragmatic pathology is of paramount importance. Diaphragmatic plication and/or resection of the diseased area have been reported (12,13,17,20). In order to avoid recurrences and provide samples for histology, Alifano et al. suggested that diaphragmatic resection (along with removal of endometrial implants) is preferable to single diaphragmatic plication (that leaves endometrial implants untreated) (8,47). Nevertheless, recurrences can occur even after diaphragmatic resection (8). Bagan et al. reported fewer recurrences after diaphragmatic coverage with a polyglactin mesh. In order to avoid recurrences, they suggested systematic diaphragmatic coverage, including coverage of diaphragms with normal appearance, to treat occult defects, reinforce the diaphragm, and induce adhesions to the lung (11). Diaphragmatic coverage with a polyglactin or polypropylene mesh (15), a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) mesh (19) or a bovine pericardial patch (20) have been reported with good mid-term results.

Medical treatment

Hormonal treatment as an adjunct to surgery prevents recurrences of catamenial and/or endometriosis-related pneumothorax. Multidisciplinary management and administration of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue (leading to amenorrhea), in the immediate postoperative period, for 6-12 months is suggested for all patients with proven catamenial and/or endometriosis-related pneumothorax (5,6,11-13,15,17,19,20,37). In our opinion, hormonal treatment may be beneficial for patients without documented catamenial character and/or histologically proven thoracic endometriosis in the presence of characteristic lesions (20). The goal of early GnRH analogues administration is to prevent cyclic hormonal changes and induce suppression of ectopic endometrium activity, until accomplishment of effective pleurodesis, since time is required for formation of effective pleural adhesions (47).

Longer period of hormonal treatment (median 17.5 months) has been required after reoperations for catamenial and/or endometriosis-related pneumothorax. Contraindications to hormonal treatment include proven ineffectiveness or significant side effects (8).

Results of treatment

Surgery for catamenial and/or endometriosis-related pneumothorax has practically zero mortality and no significant morbidity. Recurrence is the most common complication, occurring in 8-40% of patients at a mean follow-up of about 4 years. The high recurrence rates, exceed by far those of surgically treated “idiopathic” pneumothorax (5,6,8,11,13,15,17,20).

Alifano et al. reported that among 114 women operated for recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax, the highest postoperative recurrence rate was observed in CP (32%), followed by non-catamenial endometriosis-related pneumothorax (27%), while the recurrence rate was only 5.3% in non-catamenial non endometriosis-related pneumothorax patients, at a mean follow-up of 32.7 months (5).

Attaran et al. reported a low recurrence rate (1 in 12, at a mean follow-up of 45.8 months), by video thoracoscopic abrasion/pleurectomy, diaphragmatic repair and PTFE mesh coverage in the presence of diaphragmatic defects, and routine postoperative hormonal treatment (19).

Incomplete surgical management of the lesions and/or no adjunctive hormonal treatment in the immediate postoperative period (17,19,20,47-62) may increase the risk of recurrences (20,63-80).

Endometriosis-related pneumothorax has been revealed even after hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy for pelvic endometriosis (2,32). Nevertheless, in our opinion, investigation and early treatment of (even asymptomatic) pelvic endometriosis is essential for the prevention of thoracic spread (20).

Conclusions

Disease awareness, early diagnosis, surgical treatment that addresses all thoracic pathology including diaphragmatic repair, and multidisciplinary approach with early postoperative hormonal treatment that deals with the main chronic systemic disease may lead to improved results, mainly reduced recurrence rates of catamenial and/or endometriosis related pneumothorax (3-8,11-13,17,19,20,33).

Acknowledgements

We thank the editor of the Journal of Thoracic Disease (JTD) for granting permission to reprint the figures in included in our relevant article.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fonseca P. Catamenial pneumothorax: a multifactorial etiology. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;116:872-3. [PubMed]

- Alifano M, Venissac N, Mouroux J. Recurrent pneumothorax associated with thoracic endometriosis. Surg Endosc 2000;14:680. [PubMed]

- Alifano M, Roth T, Broët SC, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: a prospective study. Chest 2003;124:1004-8. [PubMed]

- Alifano M, Trisolini R, Cancellieri A, et al. Thoracic Endometriosis: current Knowledge. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:761-9. [PubMed]

- Alifano M, Jablonski C, Kadiri H, et al. Catamenial and noncatamenial, endometriosis-related or nonendometriosis-related pneumothorax referred for surgery. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:1048-53. [PubMed]

- Alifano M. Catamenial pneumothorax. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2010;16:381-6. [PubMed]

- Rousset-Jablonski C, Alifano M, Plu-Bureau G, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax and endometriosis-related pneumothorax: clinical features and risk factors. Hum Reprod 2011;26:2322-9. [PubMed]

- Alifano M, Legras A, Rousset-Jablonski C, et al. Pneumothorax recurrence after surgery in women: clinicopathologic characteristics and management. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;92:322-6. [PubMed]

- Van Schil PE, Vercauteren SR, Vermeire PA, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax caused by thoracic endometriosis. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;62:585-6. [PubMed]

- Cowl CT, Dunn WF, Deschamps C. Visualization of diaphragmatic fenestration associated with catamenial pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;68:1413-4. [PubMed]

- Bagan P, Le Pimpec Barthes F, Assouad J, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: retrospective study of surgical treatment. Ann Thorac Surg 2003;75:378-81. [PubMed]

- Korom S, Canyurt H, Missbach A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax revisited: clinical approach and systematic review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;128:502-8. [PubMed]

- Marshall MB, Ahmed Z, Kucharczuk JC, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: optimal hormonal and surgical management. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;27:662-6. [PubMed]

- Peikert T, Gillespie DJ, Cassivi SD. Catamenial pneumothorax. Mayo Clin Proc 2005;80:677-80. [PubMed]

- Leong AC, Coonar AS, Lang-Lazdunski L. Catamenial pneumothorax: surgical repair of the diaphragm and hormone treatment. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006;88:547-9. [PubMed]

- Mikroulis DA, Didilis VN, Konstantinou F, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;56:374-5. [PubMed]

- Ciriaco P, Negri G, Libretti L, et al. Surgical treatment of catamenial pneumothorax: a single centre experience. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009;8:349-52. [PubMed]

- Majak P, Langebrekke A, Hagen OM, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax, clinical manifestations-a multidisciplinary challenge. Pneumonol Alergol Pol 2011;79:347-50. [PubMed]

- Attaran S, Bille A, Karenovics W, et al. Videothoracoscopic repair of diaphragm and pleurectomy/abrasion in patients with catamenial pneumothorax: a 9-year experience. Chest 2013;143:1066-9. [PubMed]

- Visouli AN, Darwiche K, Mpakas A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: a rare entity? Report of 5 cases and review of the literature. J Thorac Dis 2012;4:17-31. [PubMed]

- Triponez F, Alifano M, Bobbio A, et al. Endometriosis-related spontaneous diaphragmatic rupture. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010;11:485-7. [PubMed]

- Parker CM, Nolan R, Lougheed MD. Catamenial hemoptysis and pneumothorax in a patient with cystic fibrosis. Can Respir J 2007;14:295-7. [PubMed]

- Schoenfeld A, Ziv E, Zeelel Y, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax-a literature review and report of an unusual case. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1986;41:20-4. [PubMed]

- Yoshioka H, Fukui T, Mori S, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax in a pregnant patient. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;53:280-2. [PubMed]

- Hamacher J, Bruggisser D, Mordasini C. Menstruation-associated (catamenial) pneumothorax and catamenial hemoptysis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1996;126:924-32. [PubMed]

- Shiraishi T. Catamenial pneumothorax: report of a case and review of the Japanese and non-Japanese literature. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1991;39:304-7. [PubMed]

- Blanco S, Hernando F, Gómez A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax caused by diaphragmatic endometriosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;116:179-80. [PubMed]

- Lillington GA, Mitchell SP, Wood GA. Catamenial pneumothorax. JAMA 1972;219:1328-32. [PubMed]

- Walker CM, Takasugi E, Chung JH, et al. Tumorlike Conditions of the pleura. Radiographics 2012;32:971-85. [PubMed]

- Suzuki S, Yasuda K, Matsumura Y, et al. Left-side catamenial pneumothorax with endometrial tissue on the visceral pleura. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;54:225-7. [PubMed]

- Laws HL, Fox LS, Younger JB. Bilateral catamenial pneumothorax. Arch Surg 1977;112:627-8. [PubMed]

- Nezhat C, King LP, Paka C, et al. Bilateral thoracic endometriosis affecting the lung and diaphragm. JSLS 2012;16:140-2. [PubMed]

- Joseph J, Sahn SA. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: new observations from an analysis of 110 cases. Am J Med 1996;100:164-70. [PubMed]

- Channabasavaiah AD, Joseph JV. Thoracic endometriosis: revisiting the association between clinical presentation and thoracic pathology based on thoracoscopic findings in 110 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010;89:183-8. [PubMed]

- Bagan P, Berna P, Assouad J, et al. Value of cancer antigen 125 for diagnosis of pleural endometriosis in females with recurrent pneumothorax. Eur Respir J 2008;31:140-2. [PubMed]

- Attaran M, Falcone T, Goldberg J. Endometriosis: Still tough to diagnose and treat. Cleve Clin J Med 2002;69:647-53. [PubMed]

- Hagneré P, Deswarte S, Leleu O. Thoracic endometriosis: A difficult diagnosis. Rev Mal Respir 2011;28:908-12. [PubMed]

- Bobbio A, Carbognani P, Ampollini L, et al. Diaphragmatic laceration, partial liver herniation and catamenial pneumothorax. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2007;15:249-51. [PubMed]

- Pryshchepau M, Gossot D, Magdeleinat P. Unusual presentation of catamenial pneumothorax. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2010;37:1221. [PubMed]

- Nakamura H, Konishiike J, Sugamura A, et al. Epidemiology of spontaneous pneumothorax in women. Chest 1986;89:378-82. [PubMed]

- Shearin RP, Hepper NG, Payne WS. Recurrent spontaneous pneumothorax concurrent with menses. Mayo Clin Proc 1974;49:98-101. [PubMed]

- Downey DB, Towers MJ, Poon PY, et al. Pneumoperitoneum with catamenial pneumothorax. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1990;155:29-30. [PubMed]

- Jablonski C, Alifano M, Regnard JF, et al. Pneumoperitoneum associated with catamenial pneumothorax in women with thoracic endometriosis. Fertil Steril 2009;91:930.e19-22.

- Grunewald RA, Wiggins J. Pulmonary endometriosis mimicking acute abdomen. Postgrad Med J 1988;64:865-6. [PubMed]

- Roth T, Alifano M, Schussler O, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: chest X-ray sign and thoracoscopic treatment. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:563-5. [PubMed]

- Andrade-Alegre R, González W. Catamenial pneumothorax. J Am Coll Surg 2007;205:724. [PubMed]

- Alifano M, Magdeleinat P, Regnard JF. Catamenial pneumothorax: some commentaries. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2005;129:1199. [PubMed]

- Morcos M, Alifano M, Gompel A, et al. Life-threatening endometriosis-related hemopneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:726-9. [PubMed]

- Slasky BS, Siewers RD, Lecky JW, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: the roles of diaphragmatic defects and endometriosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;138:639-43. [PubMed]

- Picozzi G, Beccani D, Innocenti F, et al. MRI features of pleural endometriosis after catamenial haemothorax. Thorax 2007;62:744. [PubMed]

- Makhija Z, Marrinan M. A Case of Catamenial Pneumothorax with Diaphragmatic Fenestrations. J Emerg Med 2012;43:e1-3. [PubMed]

- Kumakiri J, Kumakiri Y, Miyamoto H, et al. Gynecologic evaluation of catamenial pneumothorax associated with endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2010;17:593-9. [PubMed]

- Kronauer CM. Images in clinical medicine. Catamenial pneumothorax. N Engl J Med 2006;355:e9. [PubMed]

- Tsakiridis K, Mpakas A, Kesisis G, et al. Lung inflammatory response syndrome after cardiac-operations and treatment of lornoxicam. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S78-98. [PubMed]

- Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis P, Vretzkakis G, et al. Effect of lornoxicam in lung inflammatory response syndrome after operations for cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S7-20. [PubMed]

- Argiriou M, Kolokotron SM, Sakellaridis T, et al. Right heart failure post left ventricular assist device implantation. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S52-9. [PubMed]

- Madesis A, Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis P, et al. Review of mitral valve insufficiency: repair or replacement. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S39-51. [PubMed]

- Siminelakis S, Kakourou A, Batistatou A, et al. Thirteen years follow-up of heart myxoma operated patients: what is the appropriate surgical technique? J Thorac Dis 2014;6 Suppl 1:S32-8. [PubMed]

- Foroulis CN, Kleontas A, Karatzopoulos A, et al. Early reoperation performed for the management of complications in patients undergoing general thoracic surgical procedures. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S21-31. [PubMed]

- Nikolaos P, Vasilios L, Efstratios K, et al. Therapeutic modalities for Pancoast tumors. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S180-93. [PubMed]

- Koutentakis M, Siminelakis S, Korantzopoulos P, et al. Surgical management of cardiac implantable electronic device infections. J Thorac Dis 2014;6 Suppl 1:S173-9. [PubMed]

- Spyratos D, Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, et al. Preoperative evaluation for lung cancer resection. J Thorac Dis 2014;6 Suppl 1:S162-6. [PubMed]

- Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P, Spyratos D, et al. Pneumothorax and asthma. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S152-61. [PubMed]

- Panagopoulos N, Leivaditis V, Koletsis E, et al. Pancoast tumors: characteristics and preoperative assessment. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S108-15. [PubMed]

- Zarogoulidis P, Chatzaki E, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusion by suicide gene therapy in advanced stage lung cancer: a case series and literature review. Cancer Gene Ther 2012;19:593-600. [PubMed]

- Papaioannou M, Pitsiou G, Manika K, et al. COPD assessment test: a simple tool to evaluate disease severity and response to treatment. COPD 2014;11:489-95. [PubMed]

- Boskovic T, Stanic J, Pena-Karan S, et al. Pneumothorax after transthoracic needle biopsy of lung lesions under CT guidance. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S99-107. [PubMed]

- Papaiwannou A, Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, et al. Asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (ACOS): current literature review. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S146-51. [PubMed]

- Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, Kioumis I, et al. Experimentation with inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Int J Pharm 2014;461:411-8. [PubMed]

- Bai C, Huang H, Yao X, et al. Application of flexible bronchoscopy in inhalation lung injury. Diagn Pathol 2013;8:174. [PubMed]

- Zarogoulidis P, Kioumis I, Porpodis K, et al. Clinical experimentation with aerosol antibiotics: current and future methods of administration. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013;7:1115-34. [PubMed]

- Zarogoulidis P, Pataka A, Terzi E, et al. Intensive care unit and lung cancer: when should we intubate? J Thorac Dis 2013;5:S407-12. [PubMed]

- Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Petermann A, Visouli A, et al. Successful application of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation due to pulmonary hemorrhage secondary to granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013;7:627-33. [PubMed]

- Zarogoulidis P, Kontakiotis T, Tsakiridis K, et al. Difficult airway and difficult intubation in postintubation tracheal stenosis: a case report and literature review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2012;8:279-86. [PubMed]

- Zarogoulidis P, Tsakiridis K, Kioumis I, et al. Cardiothoracic diseases: basic treatment. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S1. [PubMed]

- Kolettas A, Grosomanidis V, Kolettas V, et al. Influence of apnoeic oxygenation in respiratory and circulatory system under general anaesthesia. J Thorac Dis 2014;6 Suppl 1:S116-45. [PubMed]

- Turner JF, Quan W, Zarogoulidis P, et al. A case of pulmonary infiltrates in a patient with colon carcinoma. Case Rep Oncol 2014;7:39-42. [PubMed]

- Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol 2013;8:194. [PubMed]

- Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis P. An interview between a pulmonologist and a thoracic surgeon-Pleuroscopy: the reappearance of an old definition. J Thorac Dis 2013;5:S449-51. [PubMed]

- Huang H, Li C, Zarogoulidis P, et al. Endometriosis of the lung: report of a case and literature review. Eur J Med Res 2013;18:13. [PubMed]