A cross-sectional evaluation of the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patient satisfaction and quality of life with a care coordinator

Introduction

Access to specialized multidisciplinary teams is recommended by international guidelines as best-treatment for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), an incurable progressive fibrotic lung disease with poor prognosis (1-3). Optimal IPF patient management may include access to a dedicated team of allied health care providers, including a care coordinator, that understands the benefits and potential adverse effects of anti-fibrotic therapy and multifaceted symptomatic management of patients. Specialized care teams have proven effective in the management of complex disease states including stroke, musculoskeletal disorders, and cancer metastasis (4-6). These teams have been associated with improvements in prognosis, patient independence and satisfaction. Patient satisfaction has been identified as a key outcome in effective IPF patient-centered care (2).

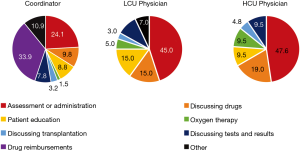

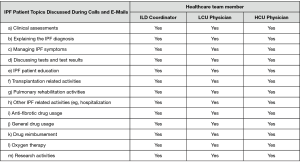

To our knowledge, although considered important for care, the impact of interprofessional care teams on patient satisfaction and health related quality of life (HRQoL) has not been formally evaluated in a Canadian IPF population (7). Within an interprofessional team, a coordinator can impact many aspects of care; for example, activities assisted by the coordinator at the Firestone Institute for Respiratory Health (FIRH) are presented (Figure 1). A coordinator is similar to a specialist IPF nurse (2,3) with additional responsibilities including indirect (e.g., drug reimbursement applications) and palliative care, and research coordination. An IPF care coordinator has the potential to improve treatment compliance through early recognition and management of drug related adverse events by providing education, support and empowerment to IPF patients (8,9). Evidence describing the patient and physician support provided by a coordinator is limited. The primary objective of this cross-sectional study was to evaluate the impact of a coordinator on IPF patient satisfaction and HRQoL. The secondary objective was to assess the economic impact of including a coordinator in the management of IPF patients at the FIRH.

Methods

Study design & participants

This single-site, cross-sectional study recruited 40 IPF patients attending interstitial lung disease (ILD) clinics at the FIRH at St. Joseph’s Healthcare (Hamilton, Ontario, Canada) between November 2017 and September 2018. Twenty patients were recruited from the practice of a physician with high coordinator use (HCU) and twenty patients from a physician with low coordinator use (LCU). In the HCU clinic, the coordinator was involved with patient management, education, treatment, research and administration, while the coordinator only assisted with treatment related tasks in the LCU clinic. Differentiation between the LCU and HCU clinics was based upon established clinical practices in each clinic and physician preference. The same coordinator attended both the LCU and HCU clinics. Inclusion criteria for the study were the diagnosis of IPF at least six months previously, and attendance to the FIRH ILD clinic. Exclusion criteria were patient age (<18) and lack of ability to communicate with study staff.

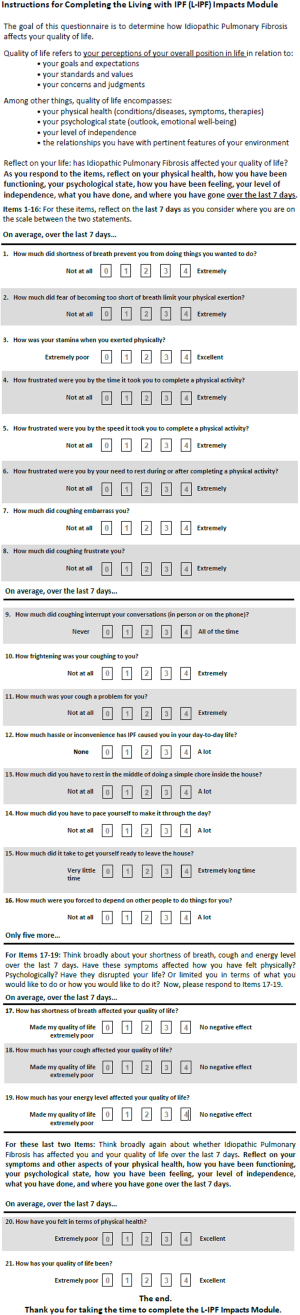

Patient reported outcomes

Patient satisfaction was assessed through the modified FAMCARE-13 (FAMCARE) survey (10) and the modified IPF Care UK Patient Support Program (UK-CARE) survey (2). The UK-CARE survey was developed to assess the satisfaction of IPF patients with care provided by an IPF patient support program (9), while the FAMCARE questionnaire was designed to assess patient satisfaction in terminal cancer patients, and was thus deemed appropriate for the IPF population due to similar prognosis and risk of adverse events related to therapeutic intervention. To our knowledge, neither survey has been formally validated in IPF patients nor had a minimal clinically important difference estimated. Patient responses to the living with IPF impacts (L-IPFi) survey (11) were collected to assess HRQoL. Administered surveys are presented in Figures S1-S3. Surveys were completed immediately after regularly scheduled clinic visits. Voluntary patient testimonials regarding the coordinator role were also collected.

Other data collected

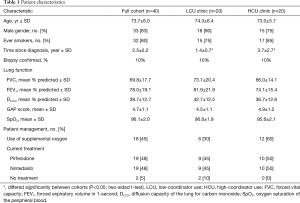

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were collected from medical records, including patient: gender, age, age at diagnosis, primary IPF physician, date and method of diagnosis, current IPF drug treatment (pirfenidone or nintedanib), pulmonary function, smoking status (never, former or current), and supplemental oxygen (Table 1). The intent of this study was not to collect adverse event information.

Full table

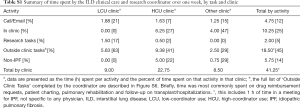

Data on the number of ILD clinics held per month, number of IPF patients seen per month, staff present within each clinic (administrators, residents, nurses and other staff), distribution of responsibilities and the frequency, duration and topic of patient-contact outside the clinic were collected via staff surveys (of the physicians and coordinator). Finally, the coordinator logged time, in 15-min increments, for five-day to detail time spent on research activities, clinical assessments, physician support, patient related administrative tasks, and patient education and management.

Statistical analyses

Study oversight, data entry, electronic database management and statistical analyses were performed by Cornerstone Research Group. Data are presented as mean ± SD or standard error of the mean (SEM), and/or median (range). Based upon published IPF patient satisfaction (2), this study had a power of 0.82 (α=0.05) to detect a difference in patient satisfaction as a result of the coordinator. Significance was assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test, at a threshold of P≤0.05, and a Bonferroni correction was applied to account for repeated testing.

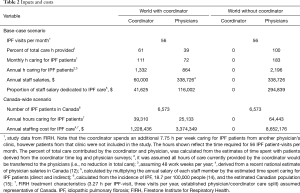

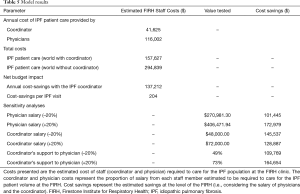

Economic analysis

The economic model compared the cost of providing care to IPF patients in a world with the coordinator (i.e., the current scenario) versus a world without the coordinator (i.e., care provided only by physicians). Costs were estimated by calculating the proportion of coordinator and specialist physician salary attributable to the management of IPF patients. Therefore, these analyses assumed that physicians were salaried rather than fee-for-service. IPF patient management costs were estimated by multiplying the total time spent on IPF patients by the physicians and coordinator at the FIRH by their respective estimated annual salaries. It was assumed that all hours that the coordinator spends caring for patients would be transferred to physicians in the world-without the coordinator. Scenario analyses were performed to test the impact of less care in the world-without the coordinator.

Estimates of total time spent on IPF patients by the physicians and coordinator were derived from staff questionnaires. The annual salary of the coordinator was informed by the research site, and the average annual salary for a specialist physician was derived from recent Canadian surveys (12,13). Model inputs are presented in Table 2. A one-way sensitivity analysis was performed by varying key inputs by ±20% and scenario analyses were performed to investigate alternative inputs (Table 2).

Full table

Ethics approval

The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice from the International Conference on Harmonization. This study was reviewed and approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (approval #3524) and the Hoffmann-La Roche global review committee. All patients enrolled completed the informed consent form. This cross-sectional study did not affect the current or future provision of care to patients that participated.

Results

Patient characteristics

Forty-one IPF patients were screened and 40 enrolled; there were no patient exclusions or drop-outs. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Most patients were males (83%) with a history of smoking (80%). Patients in the LCU clinic had a significantly shorter duration of disease at the time of enrollment, compared with HCU clinic patients; otherwise, patient characteristics were evenly distributed between the two clinics. Thirty-eight patients (95%) were receiving anti-fibrotic therapy, with pirfenidone and nintedanib used equivalently.

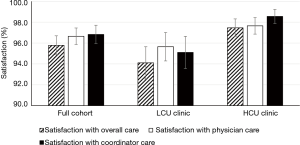

Patient reported outcomes—satisfaction

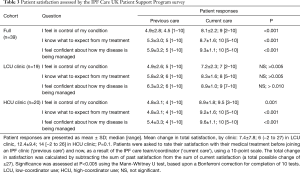

We assessed IPF patient satisfaction using the FAMCARE and UK-CARE surveys. The FAMCARE scale was developed to measure patient satisfaction with palliative care and has been validated in palliative oncology populations (10,16,17). Patients in both clinics were highly satisfied with their overall care, care provided by the physician and care provided by the coordinator, as assessed by the FAMCARE survey (Figure 2). Patients reported over 95% satisfaction with their care, and no difference between clinics was noted with the FAMCARE survey. In contrast, HCU clinic patients assessed with the UK-CARE survey reported a significant increase in satisfaction with current care compared to care before joining the IPF clinic, including increased feelings of control of disease, expectations of treatment and confidence in disease management (Table 3). Patients in the LCU clinic did not report a significant change in any parameter assessed by the UK-CARE survey. A trend (P=0.1) towards increased mean total satisfaction in the HCU clinic, compared to the LCU clinic was noted.

Full table

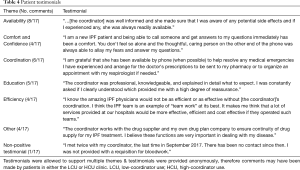

Patient testimonials

Patients voluntarily commented on their satisfaction via anonymous testimonials. Seventeen testimonials were received and reviewed for core message(s). Sixteen testimonials were positive; representative testimonials are presented in Table 4. The most common message described by patients was increased availability to care. Consistent with responses to the FAMCARE and UK-CARE surveys, testimonials reflected a positive impact of the coordinator on confidence and disease control.

Full table

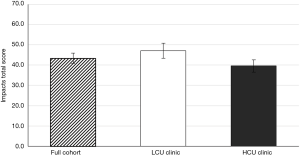

Patient reported outcomes—HRQoL

The impact of the coordinator on IPF patient HRQoL was assessed using the L-IPFi questionnaire, which was developed through IPF patient- and FDA-guided revision of the validated survey, “A Tool to Assess Quality of life in IPF” (11). The total impacts score was calculated as described elsewhere (11). All patients completed the L-IPFi questionnaire and reported a reduction in HRQoL related to their IPF; no statistical difference in HRQoL between the clinics was observed, with LCU clinic patients and HCU clinic patients having a mean impacts score of 47.1 (±SD of 16.6) and 39.6 (±SD of 15.6), respectively (Figure S4). That HCU clinic patients reported a numerically lower HRQoL than LCU clinic patients may be related to the increased time since diagnoses of the HCU clinic patients.

Economic analysis

To facilitate the economic analysis, patient and physician support provided by the coordinator and the proportion of specialist physician time devoted to IPF patient management were quantified. Time commitments and responsibilities of the coordinator and physicians are presented in Figures 1,S5,S6. At the FIRH, IPF patients received an average of 3.27 h of care (per patient visit) with the coordinator providing approximately 67% of the care in the HCU clinic and 33% in the LCU clinic. While time per patient was similar between clinics, the HCU clinic had nearly three times as many IPF patient visits (40 vs. 16 per month). Analysis of time-log data revealed the coordinator to spend 35.5 h per week caring for IPF patients (Table S1), with a ratio of approximately 2.5 h in the HCU clinic per 1 h in the LCU clinic.

Full table

In the (current) world with the coordinator, the total physician and coordinator cost to manage IPF patients was estimated to be $157,627. Provision of the same level of care without a coordinator was estimated to cost $294,839, thus the coordinator role may result in annual cost-savings of $137,212 (Table 5). As physician salary may not increase linearly with time spent with patients, an alternative analysis was performed to assess the total hours of care lost, if the coordinator role was eliminated but physicians could spend no additional time with patients. This analysis estimated that the removal of the coordinator would lead to the loss of 1,022 h of care, which is approximately 313 IPF patient visits at the FIRH. Sensitivity analyses were performed by varying the physician or coordinator salary, or the estimated division of labour by ±20% (Table 5). Physician salary was the driver of the model. Inclusion of the coordinator remained cost-saving in all sensitivity analyses.

Full table

Scenario analyses were performed to estimate the impact of implementing coordinators throughout Canada, and the size of a community IPF clinic necessary to warrant a coordinator. Parameterizing the model with the estimated total number of IPF patients in Canada (Table 4) suggests that employment of coordinators to assist specialist management of IPF patients, in the same capacity as seen at the FIRH, may result in annual cost-savings of $4,049,391 in Canada. Parameterizing the Canada-wide analysis with a published estimate of specialist time commitments (13) that could be supported by a coordinator (31%) resulted in annual cost savings of $2,055,099 in Canada. Finally, using FIRH time estimates, a community care clinic was estimated to require 294 IPF patient visits (per year) to offset the cost of one coordinator.

Interpretation

The objective of the study was to evaluate the impact of a care coordinator on IPF patient satisfaction and HRQoL. Overall, patients recruited into the LCU and HCU cohorts were well aligned, aside from the longer duration of disease in the HCU clinic. Patient satisfaction was assessed using the FAMCARE and UK-CARE surveys. As assessed by the FAMCARE survey, all patients reported high levels of satisfaction, that did not differ between clinics. Elsewhere, the FAMCARE survey has identified a correlation between patient satisfaction and the level of communication with health-care providers (17), which may indicate that the level of patient care provided at the FIRH (approximately 3.3 h per patient visit, including both the initial visit and subsequent responsibilities and care needs occurring prior to the next visit, as outlined in Figure 1) is appropriate for these patients.

Among HCU clinic patients, the UK-CARE survey showed a tendency towards greater satisfaction, and a significant increase in satisfaction when comparing care before and after joining the IPF clinic. Previous studies using the UK-CARE survey, in British and Austrian IPF patients, found a 6.1-point mean increase in satisfaction after joining the care program, which was slightly less than the benefit found here (2). Increased patient satisfaction may be related to greater access to care providers; as evidenced by testimonials and research in other disease areas (9,18,19).

That HCU clinic patients reported elevated satisfaction as a result of current care (compared with care received prior to the IPF clinic) and indistinguishable total care time required is of particular interest, given the longer duration since diagnosis of patients within the HCU clinic. The difference in time since diagnosis suggests that the HCU clinic may predominantly consist of prevalent patients with established disease, while the LCU clinic may contain relatively more recently diagnosed incident patients. Together, these data highlight that a coordinator can contribute to care of IPF patients at each stage of disease. Future investigations into the role of the coordinator should focus on patient healthcare resource use and longitudinal degradation of satisfaction/HRQoL, to enable assessment of the role of the coordinator during the transition from incident to later stages of disease.

HRQoL of IPF patients did not differ between the LCU or HCU clinic, indicating that shifting some responsibility of care from a physician to a coordinator may not compromise patient HRQoL. Similar results have been found in diabetes (20) and eczema (19). Interestingly, an IPF patient assistance program at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center was associated with a decrease in patient reported HRQoL, which prompted the conclusion that benefits of the coordinator may not be adequately captured by standard HRQoL instruments (21). Future efforts to quantify the impact of a coordinator on IPF patient health should focus on aspects of patient health, such as hospitalization rates, emergency room visits and exacerbation rates.

This study demonstrates the considerable time-commitment required for the provision of care to IPF patients. At the FIRH, the coordinator was estimated to allow for an additional 313 IPF patient visits per year. Our analyses suggest that inclusion of a coordinator in the routine management of IPF patients may result in cost-savings to institutions and potentially the Canadian healthcare system.

Limitations of the study

As patients with positive feelings toward the coordinator may have been more likely to enrol, this study was at risk of selection bias. To mitigate this risk, an impartial research coordinator screened and enrolled patients. Population differences may exist, as the two clinics differed in ways other than coordinator usage (e.g., the HCU clinic was larger and contained patients with a longer time since diagnosis), and patient comorbidity data were not collected. As this study focused on the practice of two physicians, it is plausible that physician specific factors may have contributed to study results. Finally, the study was performed at a tertiary care center with a single coordinator and sufficient IPF expertise to optimize use of the coordinator. Results may not be generalizable to smaller centers, with less expertise or patient volume. A multi-site, national study to assess the impact of a coordinator across Canada could help resolve these limitations.

The economic assessment focused on the budget impact of staffing costs, time saved, and patients seen. The model does not capture potential reductions in healthcare resource utilization or improved compliance resulting from the coordinator (22-24). Additionally, Canada-wide analyses assumed that IPF patients received optimal care, without accounting for geographical challenges.

Conclusions

In summary, we have demonstrated that inclusion of a care coordinator in the routine management of IPF patients can enhance patient satisfaction. Further, the transfer of care from the specialist physician to the coordinator was found to spare physician time without reducing patient HRQoL. Through reduction of physician time-commitments, the coordinator role was estimated to reduce the staff costs of managing IPF patients and increase the number of patients that a physician can manage. Future studies should investigate the effect of the coordinator on healthcare resource use and anti-fibrotic drug compliance.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Roche Canada. Cornerstone Research Group was contracted by Roche Canada to assist with study design, oversee the study, analyze data and provide medical writing support medical writing support. Roche Canada was involved in study design, interpretation of data and writing the report, but not the decision to submit for publication. All authors had and continue to have access to all study data.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: Daniel Grima, Daniel Moldaver and Margaret Ainslie-Garcia are employees of Cornerstone Research Group. Diana Fung, Czerysh Cabalteja and Patricia DeMarco are employees of Hoffmann-La Roche. Hoffmann-La Roche contracted Cornerstone Research Group to oversee and analyze the conduct of this study. Gerard Cox has received personal fees from Boston Scientific. Nathan Hambly has received honoraria and awarded grants from Actelion, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and Roche. Martin Kolb has received honoraria, awarded grants or consulting fees from Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Gilead, Actelion, Respivert, Alkermes, Pharmaxis, Prometic, Indalo and Third Pole. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Harmonized Tripartite Guideline for Good Clinical Practice from the International Conference on Harmonization. This study was reviewed and approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (approval #3524) and the Hoffmann-La Roche global review committee. All patients enrolled completed the informed consent form.

References

- CPFF Patient Charter - Toward Exceptional Care: A Canadian Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Patient Charter. 2016:1-8.

- Duck A, Pigram L, Errhalt P, et al. IPF Care: a support program for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treated with pirfenidone in Europe. Adv Ther 2015;32:87-107. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in adults: diagnosis and management. 2013.

- Bershad EM, Feen ES, Hernandez OH, et al. Impact of a specialized neurointensive care team on outcomes of critically ill acute ischemic stroke patients. Neurocrit Care 2008;9:287-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brendbekken R, Harris A, Ursin H, et al. Multidisciplinary Intervention in Patients with Musculoskeletal Pain: a Randomized Clinical Trial. Int J Behav Med 2016;23:1-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmieder K, Keilholz U, Combs S. The Interdisciplinary Management of Brain Metastases. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016;113:415-21. [PubMed]

- Ferrara G, Luppi F, Birring SS, et al. Best supportive care for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current gaps and future directions. Eur Respir Rev 2018. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belkin A, Swigris JJ. Patient expectations and experiences in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: implications of patient surveys for improved care. Expert Rev Respir Med 2014;8:173-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duck A, Spencer LG, Bailey S, et al. Perceptions, experiences and needs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Adv Nurs 2015;71:1055-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lo C, Burman D, Hales S, et al. The FAMCARE-Patient scale: measuring satisfaction with care of outpatients with advanced cancer. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:3182-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Graney B, Johnson N, Evans CJ, et al. Living with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (L-IPF): Developing a Patient-Reported Symptom and Impact Questionnaire to Assess Health-Related Quality of Life in IPF. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;195:A5353.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. Physicians in Canada 2016.

- Canadian Medical Association. Physician Workforce Survey, 2017. National Results for Anesthesiologists. Question 13 Average weekly work hours.

- Hopkins RB, Burke N, Fell C, et al. Epidemiology and survival of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis from national data in Canada. Eur Respir J 2016;48:187-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Population and Dwelling Count Highlight Tables, 2016 Census. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/hlt-fst/pd-pl/index-eng.cfm

- Chattat R, Ottoboni G, Zeneli A, et al. The Italian version of the FAMCARE scale: a validation study. Support Care Cancer 2016;24:3821-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parpa E, Galanopoulou N, Tsilika E, et al. Psychometric Properties of the Patients' Satisfaction Instrument FAMCARE-P13 in a Palliative Care Unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2017;34:597-602. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Russell AM, Ripamonti E, Vancheri C. Qualitative European survey of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: patients' perspectives of the disease and treatment. BMC Pulm Med 2016;16:10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schuttelaar ML, Vermeulen KM, Coenraads PJ. Costs and cost-effectiveness analysis of treatment in children with eczema by nurse practitioner vs. dermatologist: results of a randomized, controlled trial and a review of international costs. Br J Dermatol 2011;165:600-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arts EE, Landewe-Cleuren SA, Schaper NC, et al. The cost-effectiveness of substituting physicians with diabetes nurse specialists: a randomized controlled trial with 2-year follow-up. J Adv Nurs 2012;68:1224-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lindell KO, Olshansky E, Song MK, et al. Impact of a disease-management program on symptom burden and health-related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and their care partners. Heart Lung 2010;39:304-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chuang C, Levine SH, Rich J. Enhancing cost-effective care with a patient-centric chronic obstructive pulmonary disease program. Popul Health Manag 2011;14:133-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coen J, Curry K. Improving Heart Failure Outcomes: The Role of the Clinical Nurse Specialist. Crit Care Nurs Q 2016;39:335-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cramm JM, Nieboer AP. The relationship between self-management abilities, quality of chronic care delivery, and wellbeing among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in The Netherlands. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2013;8:209-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]