The management of sepsis: science & fiction

This special edition of the Journal of Thoracic Disease (JTD) explores emerging concepts in the management of patients with sepsis and septic shock. Sepsis has been a leading cause of death in humans since the dawn of mankind. Data suggests that almost half the entire population of Europe and Asia were wiped out in the Black Death plague of the early 15th century. More recently between 50–100 million patients were estimated to have died during the 1918 influenza pandemic (1); most of these deaths being due to bacterial pneumonia (2). The causation and treatments of sepsis have been shrouded with superstition since the earliest times (3). The Chinese utilized moldy soybean curd to treat infections some 2,500 years ago (3). Hippocrates (460–370 BC) the “father of medicine” popularized the concept of “dysregulated body humors” as a cause of disease and used myrrh, wine, and inorganic salts to treat infected wounds. Galen (129–199 AD) a prominent Roman physician, devoted much of his practice to bloodletting and the use of “medicinals” including theriac, a mixture of over 70 substances (4). Bloodletting remained a popular treatment for sepsis and was the treatment of choice for cholera in the European epidemic of 1832 (5). The most important advance in our understanding of sepsis came in 1878 when Louis Pasteur [1822–1895] proposed the “germ theory”. This was followed by the discovery of penicillin by Sir Alexander Fleming [1881–1955] in 1929. Following the discovery of penicillin numerous other antibiotics followed and the understanding and treatment of infectious diseases advanced significantly. However, there were also a number of setbacks, most notably the formation of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign in 2004 (6). Ostensibly to improve the outcome of patients with sepsis, this endeavor was conceived by Eli Lilly and Company to promote the sales of their drug (Xigris) (7). More recent iterations of this guideline have dominated the approach to patients with sepsis (8,9), however, unfortunately, much like the approaches of Hippocrates and Galen many of the recommendations of these guidelines are based on myths and personal beliefs (Grade level of evidence: expert opinion) (10). Indeed, many of these recommendations may be harmful (see Table 1) (11-13). These concepts are highlighted in the reviews by Spiegel et al., Marik et al., and Wang et al. (14-16). While we believe that the approach to patients with sepsis should be personalized rather than based on rigid protocols (17), a number of basic principles are critical, these include:

- Early diagnosis. The early diagnosis of sepsis is critical to achieve a good outcome. This requires a high index of suspicion and the realization that up to 40% of patients with septic shock may present with vague non-specific symptoms (18). In addition, readily available tests including the complete blood count and differential and procalcitonin may aid in the early diagnosis of sepsis. These tests are reviewed in the papers of Farkas and Gregoriano et al. respectively (19,20).

- Early and appropriate antibiotics. Antibiotics should be administered as soon as feasible; however, artificial time constraints lack scientific validity. This topic is reviewed Schinkel et al. (21).

- Early source control. The septic episode will not resolve until source control is achieved.

- An individualized, physiologically guided, conservative approach to fluid management. This topic is reviewed by Marik et al. (15).

- The early use of norepinephrine in patients with septic shock. This approach is reviewed by Hamzaoui and Shi (22).

- The early use of adjunctive supportive therapy including thiamine and vitamin C. This topic is summarized by Moskovitz et al. and Marik (23). In addition, the scientific rationale for using melatonin as adjunctive therapy for sepsis is reviewed by Colunga Biancatelli et al. (24).

Full table

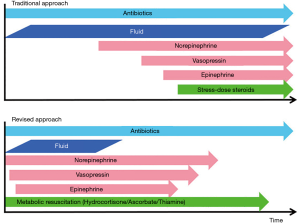

The evidence based “revised” approach to the management of patients with sepsis is summarized in Figure 1 (25). Recent publications suggest that the incidence of sepsis has increased substantially while the mortality has decreased. This may, however, be an artifactual observation due to changes in the definitions of sepsis. This is an important concept as the changing definitions of sepsis may account for claims of improved outcomes in observational cohort studies that span a number of years (26). This is illustrated by a study which claimed a dramatic (>50%) decline in sepsis mortality with the introduction of early goal-directed therapy (EGDT) (27), whereas in reality the mortality likely increased (28). This topic will be reviewed by Rhee and Klompass (29). Finally, over the last two decades countless dozens of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been performed testing novel approaches to sepsis. Twenty-eight- or 90-day mortality were the primary end-points in almost all of these studies. While RCTs are considered the “Golden Standard” by which to judge the efficacy of an intervention, in the critically ill patients RCT’s have many limitations. These include patient heterogeneity, non-standardized co-interventions, numerous exclusion criteria and delays in instituting therapy, to name but a few. Girbes and de Grooth make a plea that it is time to stop randomized and large pragmatic trials for intensive care unit (ICU) syndromes (30).

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Morens DM, Fauci AS. The 1918 influenza pandemic: insights for the 21st century. J Infect Dis 2007;195:1018-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brundage JF, Shanks GD. Deaths from bacterial pneumonia during 1918-19 influenza pandemic. Emerg Infect Dis 2008;14:1193-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Funk DJ, Parrillo JE, Kumar A. Sepsis and septic shock: a history. Crit Care Clin 2009;25:83-101. viii. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thurston AJ. Of blood, inflammation and gunshot wounds: the history of the control of sepsis. Aust N Z J Surg 2000;70:855-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Latta TA. Relative to the treatment of cholera by the copious injection of aqueous and saline fluid into the veins. Lancet 1832;2:274-77.

- Dellinger RP, Carlet JM, Masur H, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 2004;32:858-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eichacker PQ, Natanson C, Danner RL. Surviving sepsis--practice guidelines, marketing campaigns, and Eli Lilly. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1640-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013;41:580-637. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med 2017;45:486-552. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sims CR, Warner MA, Stelfox HT, et al. Above the GRADE: evaluation of guidelines in critical care medicine. Crit Care Med 2019;47:109-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Klompas M, Rhee C. Current sepsis mandates are overly prescriptive, and some aspects may be harmful. Crit Care Med 2018. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spiegel R, Farkas JD, Rola P, et al. The 2018 Surviving Sepsis Campaign’s treatment bundle: when guidelines outpace the evidence supporting their use. Ann Emerg Med 2019;73:356-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- IDSA Sepsis Task Force. Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) position statement: why IDSA did not endorse the surviving sepsis campaign guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:1631-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marik PE. The management of sepsis: science & fiction. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S1-4.

- Marik PE, van Haren F, Byrne L. Fluid resuscitation in sepsis: the great 30 mL per kg hoax. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S37-47.

- Wang J, Strich JR, Applefeld WN, et al. Driving blind: instituting SEP-1 without high quality outcomes data. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S22-36.

- Singer M. Sepsis: personalization v protocolization? Crit Care 2019;23:127. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Filbin MR, Lynch J, Gillingham TD, et al. Presenting symptoms independently predict mortality in septic shock: importance of a previously unmeasured confounder. Crit Care Med 2018;46:1592-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farkas JD. The complete blood count to diagnose septic shock. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S16-21.

- Gregoriano C, Heilmann E, Molitor A, et al. Role of procalcitonin use in the management of sepsis. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S5-15.

- Schinkel M, Nannan Panday RS, Wiersinga WJ, et al. Timeliness of antibiotics for patients with sepsis and septic shock. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S66-71.

- Hamzaoui O, Shi R. Early norepinephrine use in septic shock. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S72-77.

- Marik PE. Vitamin C: an essential “stress hormone” during sepsis. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S84-8.

- Colunga Biancatelli RML, Berrill M, Mohammed YH, et al. Melatonin for the treatment of sepsis: the scientific rationale. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S54-65.

- Marik PE, Farkas JD. The changing paradigm of sepsis: early diagnosis, early antibiotics, early pressors, and early adjuvant treatment. Crit Care Med 2018;46:1690-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scheer CS, Fuchs C, Kuhn SO, et al. Quality improvement initiative for severe sepsis and septic shock reduces 90-day mortality: a 7.5-year observational study. Crit Care Med 2017;45:241-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whippy A, Skeath M, Crawford B, et al. Kaiser Permanente’s performance improvement system, part 3: multisite improvements in care for patients with sepsis. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2011;37:483-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Durston W. Does adoption of a regional sepsis protocol reduce mortality? Am J Emerg Med 2014;32:280-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rhee C, Klompas M. Sepsis trends: increasing incidence and decreasing mortality, or changing denominator? J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S89-100.

- Girbes ARJ, de Grooth HJ. Time to stop randomized and large pragmatic trials for intensive care medicine syndromes: the case of sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:S101-9.