Brachiocephalic vein aneurysm: a systematic review of the literature

Introduction

Brachiocephalic vein (or innominate vein) aneurysms are extremely rare. To date, there have only been 36 cases reported in the literature. Brachiocephalic vein aneurysms are more common on the left than on the right side and are often saccular rather than fusiform (1-11). The majority of brachiocephalic vein aneurysms are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on imaging, though some may present with mass effect on adjacent structures or rupture (2,10-17). As such, the basis of therapy is to prevent aneurysmal progression, thromboembolism or mass effect on adjacent structures, or rupture. While multiple treatment options are available, established guidelines regarding therapy for brachiocephalic vein aneurysms are lacking. The present systematic review aims to describe the etiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, current management options and outcomes of brachiocephalic vein aneurysms.

Etiology

With the exception of trauma and iatrogenic causes, the true etiology of brachiocephalic vein aneurysms is not well understood. A number of conditions are thought to be associated with brachiocephalic vein aneurysms, including, but not limited to congenital malformation (28%, 10/36 cases) (1,2,4,5,9,12-14,18), hemangioma (8%, 3/36 cases) (5,19,20), hygroma (3%, 1/36 cases) (21), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) (3%, 1/36 cases) (22), a history of vascular intervention (3%, 1/36 cases), tumor retraction (3%, 1/36 cases) (19), and degeneration of the vessel wall (3%, 1/36 cases) (23).

Congenital defects in vessel structure may cause brachiocephalic vein aneurysm, as described in 28% of patients (10/36 cases) (1,2,4,5,9,12-14,18). These have been reported in association with the histological absence of smooth muscle cells in the aneurysm wall or absence of the adventitia’s longitudinal muscle layer, supporting congenital weakness of the vessel wall as a potential underlying cause (4,24).

An association between brachiocephalic vein aneurysms and hemangiomas has also been described in approximately 8% of patients (3/36 reported cases) (5,19,20). Nitta et al. reported a case of congenital left and right brachiocephalic vein aneurysms in the setting of angiomatosis, a diffuse form of hemangioma (5,25,26). Akiba (19) and Nakada et al. (20) have also reported cases of thymus cavernous hemangioma in association with left brachiocephalic vein aneurysm. Pathological examination showed a transitional portion between the left brachiocephalic vein and cavernous hemangioma, and the tumor appeared to retract the lower portion of the left brachiocephalic vein (19).

Brachiocephalic vein aneurysms have also been reported in association with mediastinal cystic hygromas (3%, 1/36 cases) (21). Among 15 cases of mediastinal cystic hygroma, eight patients were found to have venous aneurysms in the neck and thorax (27). The association between hygroma and venous aneurysms has been attributed to the close embryologic relationship between the lymphatic and venous systems (28).

Finally, there has been one report (3%) of brachiocephalic vein aneurysm as a manifestation of NF1 (22). Pathological examination of the resected aneurysm demonstrated diffuse neurofibroma with an infiltrative pattern. While cardiac and peripheral vascular problems are known clinical complications of NF1 (29), venous aspects of the disorder are poorly understood. Only three other cases of venous aneurysms have been reported in the setting of NF1, all of which involved the internal jugular vein (29-31). Although venous aneurysms are extremely rare manifestations of NF1, they remain a possible finding.

Presentation

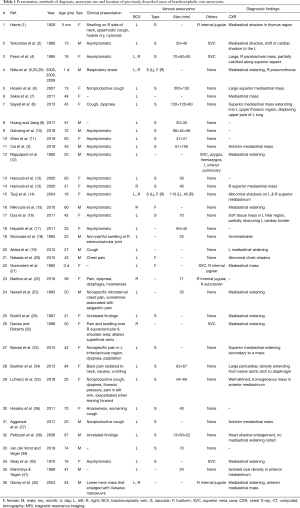

The majority of patients with brachiocephalic vein aneurysms are asymptomatic (36%, 13/36 cases) (Table 1) (2,10-17).

Full table

When symptomatic, brachiocephalic vein aneurysms present with swelling over the supraclavicular and shoulder area (8%, 3/36 cases) (1,18,32), pain (19%, 7/36 cases) (20,22,23,32-35), and cough (19%, 7/36 cases) (1,6,8,19,35-37). Additionally, large or thrombosed aneurysms can have a mass effect on adjacent mediastinal structures, causing other symptoms such as hoarseness (8%, 3/36 cases), dyspnea (11%, 4/36 cases), and respiratory arrest (3%, 1/36 cases).

Diagnosis

Brachiocephalic vein aneurysms are often incidental findings (56%, 20/36 cases). Widening of the mediastinum (28%, 10/36 cases) or presence of a mediastinal mass (47%, 17/36 cases) are the most common findings on chest radiographs. When incidental thoracic masses are suspected, they are often further characterized by computed tomography (CT) (conventional, contrast-enhanced CT or 3D CT) or venography [conventional, CT venography, or magnetic resonance (MR) venography]. Other imaging modalities for the diagnosis of brachiocephalic vein aneurysms include echocardiography, MR imaging (MRI) or duplex ultrasound. In some cases, more invasive approaches such as exploratory thoracoscopy are necessary to confirm diagnosis (13).

On results from cross-sectional imaging methods such as CT, contrast pooling, homogeneous enhancement similar to adjacent venous structures, and continuity with the thoracic veins are often indicative of venous aneurysms (43). Although contrast-enhanced CT is often sufficient to arrive at a diagnosis of brachiocephalic vein aneurysm, common imaging pitfalls are misdiagnosis of the aneurysm as either (I) a solid mediastinal tumour (1,34) or (II) a thymoma (9). As such, should there be any suspicion for misdiagnosis; further workup should be supplemented with the use of multi-modality imaging techniques such as venography, MRI, or transthoracic Doppler study for operative planning.

Differential diagnosis

There is a wide spectrum of potential diagnoses for a mediastinal mass including thymoma, lymphoma, teratoma, neurofibroma, ectopic thyroid gland, lung neoplasm, and arterial aneurysm, among others (44). Despite its rarity, brachiocephalic vein aneurysm should be considered as a differential diagnosis upon discovery of a mediastinal mass, especially in the context of previously reported associations, including congenital malformations (1,2,4,5,9,12-14,18), hemangioma (5,19,20), hygroma (21), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) (22), a history of vascular intervention and tumor retraction (19).

Management and outcomes

While multiple treatment options are available, established guidelines regarding therapy for brachiocephalic vein aneurysms are lacking. Treatment is largely determined by clinical presentation, characteristics of the aneurysm, patient decisions, and surgical candidacy. Current treatment approaches include conservative management and surgery.

Conservative management

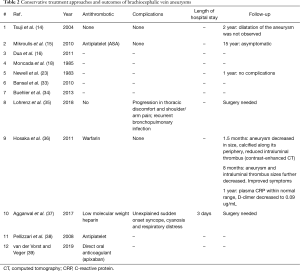

Conservative management was reported in 12/28 cases (43%) (Table 2).

Full table

This approach has been suggested as a reasonable option for patients who are asymptomatic with small, non-enlarging brachiocephalic vein aneurysms (6,14,16). The majority of patients treated conservatively had saccular brachiocephalic vein aneurysms (75%, 9/12 cases). The rest had either fusiform brachiocephalic vein aneurysms (17%, 2/12 cases) or the aneurysm type was not identified. The conservative approach is also recommended for patients who are poor surgical candidates (34) or those who do not wish to receive more invasive treatment (33). Upon presentation of thrombotic material, antithrombotic therapy should be discussed. Of the 12 patients who received conservative treatment, 4 (33%) had no complications, 2 (17%) required urgent surgery, and information on follow-up for the remaining 6 (50%) was not available.

Observation only

Conservative treatment with observation only, was reported in 7 cases (58% of patients who received conservative treatment). Of these patients, 3 had no thrombi (16,33,35), 1 had thrombus but was a poor surgical candidate (34) and the presence or absence of thrombi was not mentioned in 3 cases (14,18,23). At a 2 year (14) and 1 year follow-up (23), complications or dilation of the aneurysm were not observed in two cases (14,23). During the 2 year follow-up, one case experienced worsening of symptoms and required explorative surgery (35). Follow-up information was not mentioned for the remaining four cases (16,18,33,34).

Antiplatelet therapy

Two cases (17%) of antiplatelet therapy for brachiocephalic vein aneurysm have been described (15,38). One case was treated with ASA at 160 mg/day (15), while information on the antiplatelet drug and dosing regimen for the other case is not available (38). One patient was lost to follow-up (38) and the other was on antiplatelet treatment for 15 years and remained asymptomatic (15).

Anticoagulation

Anticoagulation with warfarin, low molecular weight heparin or direct oral anticoagulant (apixaban) have been reported in 3 cases in the management of brachiocephalic vein aneurysms (36,37,39). Of the 3 cases treated with an anticoagulant, 2 had thrombosed aneurysms (36,37) whereas 1 was continued on apixaban given pre-existing atrial fibrillation (39). One patient experienced successful reduction in size of the intraluminal thrombus and the aneurysm, as evaluated by contrast-enhanced CT at 1.5 and 8 months post-treatment. One patient treated conservatively with low-molecular weight heparin (37) developed sudden onset syncope, cyanosis and respiratory distress from the aneurysm, requiring emergency surgery. One patient was lost to follow-up (39).

Surgery

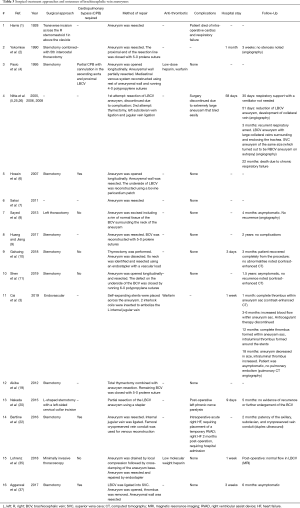

Surgery with aneurysmectomy and repair was performed in 57% of patients (16/28 cases) for brachiocephalic vein aneurysms that were symptomatic (19%, 3/16 cases) (5,8,22), saccular (69%, 11/16 cases) (1-11), expanding (12%, 2/16 cases) (6,22), or containing intraluminal thrombi (44%, 7/16 cases) (4-8,11,37) (Table 3).

Full table

Surgery was also performed to confirm diagnosis (12%, 2/16 cases) (20,35), to prevent possible major complications such as thromboembolism, rupture, or venous compression with subsequent obstruction (38%, 6/16 cases) (2-4,8,10,22), or to address aneurysmal complications (12%, 2/16 cases) (35,37).

Surgical approaches

Among the reported cases, median sternotomy was the most common surgical approach (56%, 9/16 cases) given its versatility and ease for use with cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) (2,4,6,9-11,19,22,37), followed by thoracotomy (12%, 2/16 cases) (2,8) and thoracoscopy (6%, 1/16 cases) (35). CPB was established in 4 cases (25% of patients who received surgical treatment) to provide clear anatomic details and mobilization of the aneurysm, prevent excessive blood loss, reduce the risk of embolization, and allow for decompression of the cerebral venous system in preparation for superior vena cava cross-clamping, if necessary (4,6,11,22). Endovascular treatment is also becoming a new therapeutic approach for patients with brachiocephalic vein aneurysms, as one patient (6%) was successfully treated with stent placement and coil embolization of the left brachiocephalic vein (3).

Operative outcomes

Brachiocephalic vein aneurysms were successfully resected in 81% of patients (13/16 cases). Intra-operative complications were reported in 3 cases (19%) (1,5,22,25,26). One patient died during an operation due to cardiac and respiratory failure (1). Nitta et al. reported another case where the surgery was discontinued due to friability of a large aneurysm (5). To reduce the size of the aneurysm, a thymectomy with left subclavian and jugular veins ligation was performed instead. Bartline and colleagues also described a case of intra-operative right heart failure that required implantation of a temporary right ventricular assist device (22). Post-operative complications were reported in two cases (13%), including left phrenic nerve paralysis (20) and right heart failure requiring hospitalization (22).

Patients spent 3 to 58 days in the hospital after surgical resection of brachiocephalic vein aneurysms (2,3,5,10,20,35,37). Post-operative anticoagulants (19% of patients) included heparin (4), low molecular weight heparin (35), and warfarin (3,4). One patient had heparin with bridging to warfarin for 3 months following surgery (4). One patient was on low molecular weight heparin once daily for 7 days post-operatively (35). And another patient received warfarin for 3-6 months following endovascular treatment of the brachiocephalic vein aneurysm (3).

The majority of patients (69%, 11/16 cases) had completion of follow-up. No complications or recurrence were noted in 8 cases (50%) (2,8-11,20,22,35). Symptoms were resolved in 3 cases (19%) (8,11,37). One patient died of chronic respiratory failure (26). Endovascular repair demonstrated aneurysmal shrinkage on chest CT 18 months after intervention, although increased intraluminal thrombus size was observed (3).

The prognosis of brachiocephalic vein aneurysms is good post resection with no reported cases of recurrence.

Conclusions

Brachiocephalic vein aneurysms are rare vascular lesions that often present asymptomatically as a widening of the mediastinum on the chest radiograph. Surgical aneurysmectomy is indicated in patients with symptomatic, saccular, expanding brachiocephalic vein aneurysms; those containing intraluminal thrombi; and those presenting with complications such as recurrent thromboembolism, rupture, or mass effect on surrounding structures. Surgical outcomes are acceptable with favorable prognosis post-resection and no recurrence reported.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2020.04.39). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Harris RI. Congenital venous cyst of the mediastinum. Ann Surg 1928;88:953-7. [Crossref]

- Yokomise H, Nakayama S, Aota M, et al. Systemic venous aneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg 1990;50:460-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai G, Hua Z, Xu P, et al. Endovascular Treatment for Left Innominate Vein Aneurysm: Case Report and Literature Review. J Interv Med 2019;2:35-7.

- Pasic M, Schöpke W, Vogt P, et al. Aneurysm of the superior mediastinal veins. J Vasc Surg 1995;21:505-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nitta A, Suzumura H, Kano K, et al. Congenital left brachiocephalic vein and superior vena cava aneurysms in an infant. J Pediatr 2005;147:405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hosein RBM, Butler K, Miller P, et al. Innominate venous aneurysm presenting as a rapidly expanding mediastinal mass. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:640-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sakai M, Kanzaki R, Kozuka T, et al. Left innominate venous aneurysm presenting as an anterior mediastinal mass. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1995. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sayed SA, Sahu D, Khandekar J, et al. Large aneurysm of innominate vein: Extremely rare cause of mediastinal mass. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013;29:198-9. [Crossref]

- Huang W, Jiang GN. A rare case of left innominate vein aneurysm mimicking thymoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2017;25:669-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Galvaing G, Gaudin M, Medous MT, et al. Left Brachiocephalic Venous Aneurysm: A Rare Clinical Finding. Ann Vasc Surg 2018;48:253.e5-253.e6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen J, Wang W, Li F, et al. Surgical treatment for rare isolated left innominate vein aneurysms. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2019;28:989-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rappaport DC, Ros PR, Moser RP. Idiopathic dilatation of the thoracic venous system. Can Assoc Radiol J 1992;43:385-7. [PubMed]

- Haniuda M, Numanami H, Makiuchi A, et al. Solitary aneurysm of the innominate vein. J Thorac Imaging 2000;15:205-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsuji A, Katada Y, Tanimoto M, et al. Congenital giant aneurysm of the left innominate vein: is surgical treatment required? Pediatr Cardiol 2004;25:421-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mikroulis D, Vretzakis G, Eleftheriadis S, et al. Long-term antiplatelet treatment for innominate vein aneurysm. Vasa 2010;39:262-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dua SG, Kulkarni AV, Purandare NC, et al. Isolated left innominate vein aneurysm: a rare cause of mediastinal widening. J Postgrad Med 2011;57:40-1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hayashi Y, Takayama K, Mizuguchi K. Giant brachiocephalic venous aneurysm in young woman. Heart Lung Circ 2011;20:205-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moncada R, Demos TC, Marsan R, et al. CT diagnosis of idiopathic aneurysms of the thoracic systemic veins. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1985;9:305-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akiba T, Morikawa T, Hirayama S, et al. Thymic haemangioma presenting with a left innominate vein aneurysm: insight into the aetiology. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;15:925-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakada T, Akiba T, Inagaki T, et al. Thymic Cavernous Hemangioma With a Left Innominate Vein Aneurysm. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:320-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gorenstein A, Katz S, Rein A, et al. Giant cystic hygroma associated with venous aneurysm. J Pediatr Surg 1992;27:1504-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bartline PB, McKellar SH, Kinikini DV. Resection of a Large Innominate Vein Aneurysm in a Patient with Neurofibromatosis Type 1. Ann Vasc Surg 2016;30:157.e1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Newell J, Sueoka B, Andersen CA, et al. Computerized tomographic diagnosis of isolated left brachiocephalic vein aneurysm: case report. Mil Med 1983;148:663-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ream CR, Giardina A. Congenital superior vena cava aneurysm with complications caused by infectious mononucleosis. Chest 1972;62:755-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nitta A, Nishikura K, Hirao J, et al. Congenital left brachiocephalic vein and superior vena cava aneurysms in an infant: an update. J Pediatr 2006;148:708-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nitta A, Nishikura K, Fukuda H, et al. Congenital left brachiocephalic vein and superior vena cava aneurysms in an infant: final update with autopsy findings. J Pediatr 2008;152:445-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Joseph AE, Donaldson JS, Reynolds M. Neck and thorax venous aneurysm: association with cystic hygroma. Radiology 1989;170:109-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burkill GJ, Burn PR, Padley SP. Aneurysm of the left brachiocephalic vein: an unusual cause of mediastinal widening. Br J Radiol 1997;70:837-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oderich GS, Sullivan TM, Bower TC, et al. Vascular abnormalities in patients with neurofibromatosis syndrome type I: clinical spectrum, management, and results. J Vasc Surg 2007;46:475-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nopajaroonsri C, Lurie AA. Venous aneurysm, arterial dysplasia, and near-fatal hemorrhages in neurofibromatosis type 1. Hum Pathol 1996;27:982-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belcastro M, Palleschi A, Trovato RA, et al. A rare case of internal jugular vein aneurysmal degeneration in a type 1 neurofibromatosis complicated by potentially life-threatening thrombosis. J Vasc Surg 2011;54:1170-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davies AJ, Roberts DE. Aneurysm of the left brachiocephalic vein: an unusual cause of mediastinal widening. Br J Radiol 1998;71:347-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bansal K, Deshmukh H, Popat B, et al. Isolated left brachiocephalic vein aneurysm presenting as a symptomatic mediastinal mass. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol 2010;54:462-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buehler MA, Ebrahim FS, Popa TO. Left innominate vein aneurysm: diagnostic imaging and pitfalls. Int J Angiol 2013;22:127-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lohrenz C, Rückner D, Wintzer O, et al. Large left innominate vein aneurysm presenting as an anterior mediastinal tumour in a young female. Vasa 2018;47:515-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hosaka A, Kato M, Kato I, et al. Brachiocephalic venous aneurysm with unusual clinical observations. J Vasc Surg 2011;54:77S-9S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aggarwal R, Gautam R, Jhamb D, et al. Diagnosing thoracic venous aneurysm: A contemporary imaging perspective. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2017;27:350-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pellizzari N, Carasi M, Iavernaro A, et al. Left innominate vein aneurysm finding during pacemaker lead insertion. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2008;31:627-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Vorst JR, Veger HTC. Saccular Aneurysm of the Brachiocephalic Vein. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2019;57:766. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okay NH, Bryk D, Kroop IG, et al. Phlebectasia of the jugular and great mediastinal veins. Radiology 1970;95:629-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marmolya G, Yagan R. Computed tomographic diagnosis of left innominate vein aneurysm mimicking an anterior mediastinal mass on plain films: a case report. J Thorac Imaging 1989;4:77-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Güney B, Demirpolat G, Savaş R, et al. An unusual cause of mediastinal widening: bilateral innominate vein aneurysms. Acta Radiol 2004;45:266-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ko SF, Huang CC, Ng SH, et al. Imaging of the brachiocephalic vein. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008;191:897-907. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carter BW, Marom EM, Detterbeck FC. Approaching the patient with an anterior mediastinal mass: a guide for clinicians. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:S102-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]