From female surgical resident to academic leaders: challenges and pathways forward

Introduction

Although the number of female surgeons is continuously increasing, male colleagues are still dominating as leaders. Why is it so difficult to get into positions where we make decisions not only for the treatment and wellbeing of our patients but also for teams, resources, departments or organisations? As surgeons we are used to solve problems all along, even under pressure if we are performing (emergency) surgery.

Becoming a leader is a challenge to everybody, because nobody is born a leader the same way as nobody is born a perfect surgeon. It can all be learned by continuous training. However, for women there are far more obstacles to achieve leadership positions than for man.

It is the merit of many brave women and their continuous fight in the past that women can go to university, study medicine and even become surgeons like Eleanor Davies-Colley, the first fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1911 (1). At that time, it was almost impossible to convince male colleagues that women can do surgery as well as themselves. Nowadays it is common knowledge that there is no difference between a male and a female surgeon in the way they perform surgery or make decisions during the operation. Over the years the number of female medical students has increased worldwide. In 1999, women surpassed the number of men as medical students in Germany where now more than 62% of the beginners are females (2). In Great Britain the rate is 55% (3) and even in countries were equal rights between sexes is not so well accepted the number of female students has approached almost 50% (personal communication). So, it is not a pipeline issue that women are not present in surgery or medicine. However, why is the majority of academic leaders still men?

One of the challenges in bringing forward the career of women in surgery is the general attitude in many societies that women are responsible for the upbringing of children (4). A male surgeon who becomes a father does not experience any negative impact on his career as he often expects his wife to take care of the children. The situation for a female surgeon however is much more complicated because of the double burden. In addition there is an emotional strain. The mindset of the society is changing only slowly and although many young men nowadays accept the fact that they should be involved in the upbringing of children, pregnancy and leave of work due to childbirth still is a backlash for the career of women. Especially, if they take off some time with the new born baby. Many female trainees have to interrupt their training at least partially and it can be hard for them to get restarted.

In 2008 we conducted a survey for the German Professional Board of Surgeons (BDC-Berufsverband der Deutschen Chirurgen) among the female members to analyse their attitude towards work, stress factors and ask about their work in comparison to their male colleagues (5). 1.026 women participated in the survey. 76% of women were between 30 and 49 years old, 87% were currently working actively as surgeons, some were retired or in child leave. 2/3 of the participants were board certified surgeons, 1/3 were still in training. When asked how the women judge their surgical volume in comparison to their male colleagues, 53% thought it was equal, 15% better, but 35% worse than the surgical catalogue of their male counterparts.

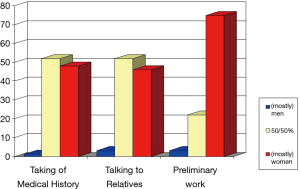

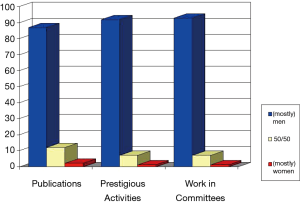

Concerning equal treatment of women and man in their own department, 65% judged that they were treated equally. However, 87% of women denied the question “Are there equal chances for women and men in surgery?”. Looking further into detail why chances were so unevenly distributed, we found that the distribution of workload in clinical practice differed quite substantially. Whereas “minor” tasks were performed in the majority by women, male colleagues dominated in “prestigious” activities. Participants estimated that “taking the medical history” in 48% was mostly done by women, 52% that it was evenly distributed between the sexes, and only 1% that it was mostly done by men. A comparable rating was found in “talking to relatives”: 52% equal distribution, 46% mainly by women, and 3% mainly by men. If asked for “preliminary work” 75% of the women felt that it was mostly done by women, only 22% found it was equally distributed and 3% judged it was mostly done by men (Figure 1). On the other hand if asked who does most of the “publications”, participants answered that this was mostly done by men in 78%, evenly distributed in 12% and done mostly by women in only 2%. As for “prestigious activities” or “work in committees” they judged in 92% that it was predominantly done by men and only 1% by women. Only 7% rated it was equally distributed between the two sexes (Figure 2). Especially these last numbers may indicate why the advancement in the career is so much harder for women than it is for men. In order to be seen by decision makers it is necessary to either publish papers, present at meetings or to meet senior leaders in committees and conferences.

Committees and networks

Through work in committees one can present good ideas and projects thereby impressing seniors and making in contact to decision makers. For a career it is extremely important to create own networks or become part of existing networks. In addition, it has the benefit of getting some information earlier than others. However, many women, if they have to choose between going into a committee meeting or caring for a patient will probably decide to do the later one. Whether this is because of responsibility, a feeling of being the only one to really care or because of being embarrassed to shuffle work to other colleagues—the result is a missed chance. Becoming visible and standing out of the crowd is important if one wants to achieve higher positions. A bias that often goes unrecognized is that women are introduced by their first names and not by their professional title or their academic achievements. This is different in men and can be experienced even by women who have achieved the highest professional levels and awards. Women should be aware of this bias and not only announce other professionals always by their professional title as well as consequently introduce themselves by full name and title(s). It may feel strange in the beginning, but it can be learned.

Mentors/sponsors

To advance in their career it is important for women to find other people (women or men) to support them, be it in their daily work or as mentors/sponsors who advocate them to higher positions. Mentoring projects are a good tool, especially if they accompany the career of a woman over a longer period of time. From my own experience it can be quite helpful to have a male mentor. Mine was an experienced head of a surgical department who gave me a lot of advice in the process of applying for a position and finally tips, how to present myself in front of a pure male decision making panel.

However, one risk of mentoring programs is that women are only getting well-meaning advice on their professional behaviour but are not encouraged in strategic planning of their career. As Shakil and Redberg state ”Women are over-mentored and under-sponsored”. Sponsorship differs from mentorship in the regard that there is a risk for the sponsor’s own reputation if they use their influence to provide an opportunity for a high rank position that their mentee would otherwise not get (6). A study has shown that the mentor-mentee sponsorship shows dramatic differences between male and female recipients of National Institute of Health grants in the US. Although sponsorship was significantly associated with success, the study noted a clear gender gap: women were less likely invited as discussant/ panellist at a national meeting, as member of a national committee or to write an editorial than their male counterparts even if they had a male sponsor. Men with male sponsors had the best chances, women with female sponsors were least successful (7).

Difference in self-presentation

The male view on candidates for leading positions is naturally biased by their own experience and behaviour. A tendency to exaggerate the own achievements is found more in men than soft skills and self-reflection. Women present themselves quite differently as they rather underestimate their competence, skills, knowledge and proficiency. The lack of self-esteem in some candidates is hindering decision makers to have faith in a woman to lead a team/department or organisation. Especially, if these men have had the disappointing experience of a female colleague whom they tried to promote and who withdrew as soon as she encountered difficulties. Some women are more likely to step aside and accept the fact that someone else is chosen instead.

Women have to learn to clearly communicate their needs and expectations to their superiors. By showing interest into a leadership position they can advocate for themselves. They should be prepared to clearly state and point out their competence to fill a position. Men in general are better in self-promotion and female surgeons have reported their experience that male colleagues whom they trained, in the end outran them for prestigious positions. However, one should not be disappointed if not considered on the first spot but continue to apply again for the next open position. The problem is that some women take it personally if they are not promoted and refrain from asking for a second chance. As mentioned above, going into discussion and presenting oneself can be learned the same way surgery can be trained. Even in a leadership position there is constant learning on the job. Leaders are always making decisions, some of them are good and some of them are bad. In order to be a good leader one has to stay critical with the own decisions and willing to adjust to new situations. Keeping this in mind, a young woman who asks for a position and is rejected by her superior should just continue to look for a similar opportunity and then try again. Perhaps a different strategy is indicated the next time she goes into the job interview.

Sometimes women are not offered leadership positions because decision makers judge the necessary skills and qualities for such a position according to their own expectations and a bias regarding female candidates. Women in surgery have to be aware of the “glass ceiling”. During training and in the early years of their professional career these limitations are in generally not seen by young high potentials. They believe that just by doing an “excellent job” and showing professionalism they will be able to achieve whatever position they wish for them. However, almost all women I know had exactly this feeling that the glass ceiling was not a problem until they noted at a certain age that men were promoted more often than themselves.

Women’s associations

To exchange view on career issues and to learn from successful female leaders/role models in thoracic surgery, women should attend the sessions of the different associations that have been founded for female surgeons worldwide. In the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (US), the group of Women in Thoracic Surgery (WTS) has the longest experience as a women’s association with their own journal, mentoring project, travelling/mentorship programmes and the Carol Reed Travelling Fellowship Award (see article in this journal). In 2006 I have initiated “FiT” (Frauen in Thoraxchirurgie = Women in Thoracic Surgery) in Germany, a working group of the German Society of Thoracic Surgery (DGT) with own sessions at the annual meeting in order to promote women in our field. The European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS) has a working group as well and in Japan there are “WTS” of the Japanese Association of Thoracic Surgeons and “JAWS” (Japanese Association of Women Surgeons) of the Japanese Surgical Society. Other female associations exist worldwide in the different fields of surgery or medicine in general.

In addition, some academic institutions have initiated special programmes to promote women into leadership positions, i.e., the Women´s Leadership Advisory Board at Boston Medical Center of Boston University (personal communication from Aviva Lee-Parritz). Equity, meaning the fair process for women and men in achieving a career in medicine and science is the major goal. This concept is shared by many and “A call for Action” was released by high ranked female leaders of different medical fields in 2016. They demand not only equal pay but also a change in the application process for grants and research funding that is blinded for gender (8).

In the German survey we also asked “Would you become a surgeon again?”. 43% of the women answered “Definitely yes”, 23% “Rather yes” adding to a total of 56%, 37% answered “Yes, but under different conditions”. Only 7% of women mentioned that they would (rather) not become a surgeon again (5). These numbers indicate that the majority of women are happy with their decision to go into a surgical field. Now it is time to change the conditions under which women can move on to prestigious positions, they have the capability to be as good as leaders as men. Then, everybody will enjoy the challenges of leadership.

Conclusion

How do we overcome obstacles we encounter while planning our career?

- Look for role models.

- Don’t let failures discourage you but try to achieve your goal in a different way.

- Look for allies/mentors/sponsors.

- Let senior people help you.

- Delegate work to younger colleagues to free up time for more prestigious work.

- Join women associations or networks.

- Believe in yourself.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editors (Cecilia Pompili and Leah Backhus) for the series “Women in Thoracic Surgery” published in Journal of Thoracic Disease. The article was sent for external peer review organized by the Guest Editors and the editorial office.

Conflicts of Interest: The author has completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-2020-wts-08. The series “Women in Thoracic Surgery” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. The author has no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Ellis H. Eleanor Davies-Colley: the first woman F.RC.S. J Perioper Pract 2009;19:118-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- . Available online: https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bildung-Forschung-Kultur/Hochschulen/Tabellen/lrbil05.htmlStatistisches Bundesamt DESTATIS.

- Pardhan S. Breaking the glass ceiling in academia. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2018;38:359-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mangurian C, Linos E, Sarkar U, et al. What’s Holding Women in Medicine Back from Leadership Harvard Business Review 2018.19.

- , Available online: https://www.bdc.de/chirurgin-in-deutschland-ergebnisse-einer-umfrage-2008/Ansorg J, Leschber G.

- Shakil S, Redberg RF. Gender Disparities in Sponsorship—How They Perpetuate the Glass Ceiling. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:582. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patton EW, Griffith KA, Jones RD, et al. Differences in Mentor-Mentee Sponsorship in Male vs Female Recipients of National Institutes of Health Grants. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:580-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bates C, Gordon L, Travis E, et al. Striving for Gender Equity in Academic Medicine Careers: A Call to Action. Acad Med 2016;91:1050-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]