Surgical modality for stage IA non-small cell lung cancer among the elderly: analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, with a median age at diagnosis of 70 years (1); thus, NSCLC is a disease of the elderly. However, age-restrictive exclusion criteria are commonplace in clinical trials. Dedicated studies need to be carefully designed to assess elderly patients due to their unique profile, multiple medical comorbidities, and increased rates of treatment-related morbidity and mortality. Approximately 10–15% of patients with NSCLC are classified into pathological stage IA (2). In the past few decades, the incidence of early-stage NSCLC has increased remarkably, largely owing to the popularization of screening methods, especially those that use low-dose computed tomography (3). Surgical treatment should be recommended as a potential cure for patients with early-stage NSCLC.

The recommended standard treatment for patients with stage IA NSCLC has been lobectomy and mediastinal lymph node dissection, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 70% (4). However, elderly patients are at risk of being intolerant to this aggressive therapy. Currently, sublobar resection is considered as an alternative surgical modality for elderly patients with early-stage NSCLC, with sublobar resection having the advantage of preserving pulmonary function which is important for these patients, especially for those at high-risk for or with multiple primary lung cancer (5-8). However, compared with lobectomy, sublobar resection is associated with a higher tumor recurrence rate and poorer long-term outcomes (4). Currently, it has not yet been clarified whether sublobar resection is oncologically equivalent to lobectomy in early-stage NSCLC, particularly among the elderly.

Since 1995, a number of retrospective studies and one randomized controlled trial (RCT) have reported results in favor of lobectomy (4,9,10). Recently, some retrospective studies have revealed that the survival in patients with localized stage IA NSCLC after sublobar resection was non-inferior to that in those who underwent lobectomy, particularly among the elderly (2,11-13). However, these controversial findings have mainly focused on assessing outcomes of surgical modalities with regard to tumor size but not the age at diagnosis. Thus, the optimal surgical modality for early-stage NSCLC as a function of age at diagnosis and tumor size remains unclear.

To address this gap in knowledge, we evaluated the population-based Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database to assess the survival in patients ≥70 years of age with stage IA NSCLC, who underwent lobectomy, segmentectomy, or wedge resection. We hypothesized that both the age at diagnosis and tumor size could play important roles on the prognosis and should be considered in the selection of a surgical modality for elderly patients with early-stage NSCLC.

We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-2221).

Methods

Study population

The SEER database is a cancer statistics registry in the US and covers almost 30% of the American population. We extracted data that concerned elderly patients (≥70-year-old) who underwent lobectomy or sublobar resection for stage IA NSCLC (from 1998 to 2016). Pathologic stage IA NSCLC was defined as stage T1a/b/c N0 M0, according to the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer criteria (14). Data for the study were extracted from 1998, because the SEER database did not differentiate segmentectomy from wedge resection until that year. We excluded patients with more than one primary NSCLC and other malignancies, as well as those who underwent chemotherapy and/or radiation treatment or had an unknown radiation and chemotherapy status. This study was based on a publicly available database; thus, it was exempted from the institutional review board approval. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Study variables

We collected data of baseline patient demographics (sex, age, marital status, and race and/or ethnicity), histopathologic information (grade, histology, and size of the tumor), and surgical modalities. In this study, tumor histology subtypes included squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and other histologic types, such as bronchioalveolar cell carcinoma and large-cell carcinoma. Tumor size was assessed not only as a continuous variable but also as a variable: ≤1 cm (T1a categorical), >1–2 cm (T1b), and >2–3 cm (T1c). Tumors were divided into well-differentiated (grade I), moderately differentiated (grade II), poorly differentiated (grade III), and undifferentiated (grade IV). Pulmonary function was not used as a variable because it was unavailable in the SEER database. Surgical modalities were classified into lobectomy, segmentectomy, and wedge resection. Overall survival (OS) and lung cancer-specific survival (LCSS), provided in the SEER database, were the primary outcomes in this study. OS was defined as the interval from the time of diagnosis to death of any cause, while LCSS was defined as the time from diagnosis to death caused by NSCLC.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were analyzed using the two-sample t-test, while categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared (χ2) test. Age at diagnosis was a continuous variable with a non-normal distribution; thus, we assessed it as a binary variable using a median age of 76 years (≥76 vs. <76 years). Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Predictors were obtained using the Cox proportional hazards model [expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs)]. Survival curves among surgical resections stratified by size of the tumor and age at diagnosis were compared using the log-rank test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 25; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). All tests were two-sided and a P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

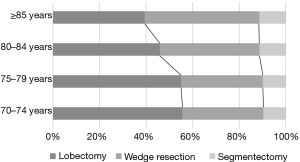

A total of 6,197 records were included; 3,279 patients were treated using lobectomies and 2918 using sublobar resections (620 segmentectomies and 2,298 wedge resections). The median follow-up time for the lobectomy and sublobar resection groups were 57 and 40.5 months, respectively. The baseline information is presented in Table 1, with key information summarized as follows. The median age at diagnosis among patients included in our study was 76 years. The patients were predominantly female (55.1%), married (52.5%), and Caucasian (88.4%). Sublobar resections were tended to be performed in more elderly patients (Figure 1), females, and those with smaller NSCLC (diameter ≤1 cm). The mean age at diagnosis was higher in the sublobar resection group than in the lobectomy group (76.7 vs. 75.8 years, P<0.001). There was no significant difference in the distribution of ethnicity.

Full table

Survival analysis of lobectomy vs. sublobar resection

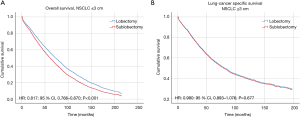

The survival analysis showed that lobectomy resulted in a significantly better OS than did sublobar resection (HR, 0.817; 95% CI, 0.766–0.870; P<0.001; Figure 2A). There was no significant difference in LCSS between the groups (P=0.677; Figure 2B). The most common causes of death, other than NSCLC, were heart disease (11.8%) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (8.9%). Thus, to exclude the potential confounding causes of death and extract the exact prognostic factors, subsequent analyses were mainly focused on LCSS.

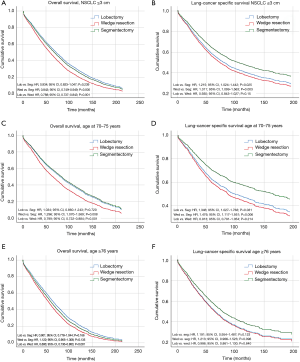

Sublobar resection was further subdivided into segmentectomy and wedge resection. Significant reductions in the OS rate were observed in the wedge resection group (Figure 3A) (segmentectomy vs. wedge: HR, 0.843; 95% CI, 0.749–0.949; P=0.005; wedge resection vs. lobectomy: HR, 1.269; 95% CI, 1.186–1.357; P<0.001) and there was no significant difference in OS between lobectomy and segmentectomy groups (P=0.239). However, lobectomy and segmentectomy resulted in different LCSS rates (HR, 1.215; 95% CI, 1.024–1.442; P=0.025), as did wedge resection and segmentectomy (HR, 1.311; 95% CI, 1.099–1.563; P=0.003), with no difference between lobectomy and wedge resection (P=0.15; Figure 3B). Overall, segmentectomy resulted in superior survival rates than did wedge resection.

The survival analyses were also performed according to the age at diagnosis, stratified as 70–75 years and ≥76 years. First, among the NSCLC patients 70–75 years of age, wedge resection resulted in a significant reduction in the OS rate (wedge vs. segmentectomy: HR, 1.296; 95% CI, 1.070–1.569; P=0.008; lobectomy vs. wedge resection: HR, 0.799; 95% CI, 0.722–0.884; P<0.001), with no significant difference in the OS rate between lobectomy and segmentectomy (P=0.720; Figure 3C). While the segmentectomy group showed superior LCSS rates (lobectomy vs. segmentectomy: HR, 1.346; 95% CI, 1.027–1.763; P=0.031; wedge resection vs. segmentectomy: HR, 1.476; 95% CI, 1.117–1.951; P=0.006), no significant difference in the LCSS rate was found between lobectomy and wedge resection (P=0.214; Figure 3D). In contrast, among patients ≥76 years of age, lobectomy was associated with superior survival than wedge resection (HR, 0.806; 95% CI, 0.736–0.883; P<0.001), with no significant difference in OS between lobectomy and segmentectomy (P=0.166) or wedge resection and segmentectomy (P=0.135; Figure 3E). Interestingly, there was no significant difference in the LCSS rate between either surgical modality (wedge vs. segmentectomy: P=0.096; lobectomy vs. wedge resection: P=0.840; lobectomy vs. segmentectomy: P=0.123; Figure 3F).

Multivariate analysis

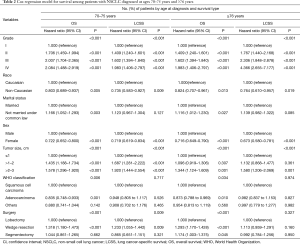

Further subgroup analysis was carried out using the Cox regression model to control for potential confounding factors (Table 2). The analysis with adjustments for patient and tumor variables indicated that wedge resection was independently associated with lower LCSS after lobectomy and segmentectomy among patients 70–75 years of age (wedge vs. lobectomy: HR: 1.233; 95% CI, 1.055–1.442; P=0.009; segmentectomy vs. wedge resection: HR: 0.699; 95% CI, 0.520–0.939, P=0.017), with no significant difference between lobectomy and segmentectomy. Among patients diagnosed at an age ≥76 years, the OS analysis favored lobectomy over both wedge resection and segmentectomy (P<0.001 and P=0.045, respectively). The HR for LCSS for wedge resection was 1.113 (P=0.16), compared with that for lobectomy; however, this was a trend with the difference not being statistically significant. In addition, higher grade, Caucasian race, larger tumor size, and male sex were identified as independent risk factors for LCSS among patients in the age groups 70–75 years or ≥76 years. It is interesting to note that unmarried patients had worse OS than the married patients in the age groups, 70–75 years and ≥76 years (70–75 years, HR: 1.166, 95% CI, 1.052–1.293, P=0.003; ≥76 years, HR: 1.116, 95% CI, 1.012–1.230, P=0.027), while no statistically significant difference was found in LCSS (P>0.05).

Full table

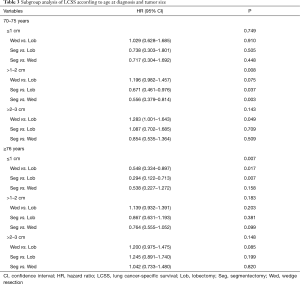

Subgroup analysis

A stratified exploratory analysis was performed to assess the appropriate surgical procedure for patients with early-stage NSCLC. The LCSS analysis for the different surgical procedures, based on the age at diagnosis and tumor size is presented in Table 3. On one hand, among the more elderly patients diagnosed at ages ≥76 years, significant reduction in LCSS was observed for tumors with a diameter ≤1 cm after lobectomy (segmentectomy vs. lobectomy: HR, 0.294; 95% CI, 0.122–0.713; P=0.007; wedge resection vs. lobectomy: HR, 0.548; 95% CI, 0.334–0.897; P=0.017), while no significant difference was observed for tumors with a diameter >1–2 or >2–3 cm. In contrast, for patients 70–75 years of age, segmentectomy was associated with better survival in patients with a NSCLC tumor diameter >1–2 cm (segmentectomy vs. lobectomy: HR, 0.671; 95% CI, 0.461–0.976; P = 0.037; segmentectomy vs. wedge resection: HR, 0.556; 95% CI, 0.379–0.814; P=0.003), with lobectomy yielding superior survival rates than wedge resection among patients with a NSCLC tumor diameter >2–3 cm (wedge resection vs. lobectomy: HR, 1.283; 95% CI, 1.001–1.643; P=0.003). However, no significant difference was observed among patients with a tumor diameter ≤1 cm.

Full table

Discussion

Currently, lobectomy is the gold-standard treatment recommended for small size NSCLC (4). However, in clinical practice, lobectomy may not be tolerated by elderly patients due to compromised pulmonary reserve and multiple commodities (15); thus, sublobar resection is an alternative for them due to the reduced morbidity, better preservation of pulmonary function, and shorter operative time (16). Some retrospective studies have suggested that survival after sublobar resection was non-inferior to that after lobectomy among patients with stage IA NSCLC (17-21). Recently, an increasing number of researchers have explored the SEER database and have drawn different conclusions. For example, Moon et al. revealed that lobectomy and segmentectomy yielded equivalent OS and LCSS rates among patients with primary NSCLC with a diameter ≤2 cm without lymph node or distant metastases (22). However, the results obtained by Dai et al. showed that lobectomy was superior to segmentectomy and wedge resection in both patients with NSCLC diameter ≤1 cm and >1–2 cm (23). Thus, there is no consensus regarding individualized treatment for patients with stage IA NSCLC and for the elderly (24). Therefore, we specifically analyzed the survival outcomes in elderly patients with stage IA NSCLC obtained from the SEER database to evaluate the role of surgical modalities in outcome and found that appropriate surgical procedures should be selected based on stratification according to the age at diagnosis and tumor size.

Previous studies have investigated the surgical resection of small size NSCLC and revealed that lobectomy and sublobar resection yielded similar levels of survival among the elderly based on the SEER database. For example, Mery et al. and Wisnivesky et al. assessed patients with early-stage NSCLC and showed that the OS advantage of lobectomy disappeared among the elderly (25,26). Similarly, Moon et al. (22), Smith et al. (27), and Razi et al. (13) demonstrated no superior OS of lobectomy among patients older than 75 years of age with a tumor size ≤2 cm. Consistent with these results, our study indicated no significant difference among surgery groups in patients ≥76 years of age with stage IA NSCLC. Furthermore, our present study revealed that among NSCLC patients 70–75 years of age, the segmentectomy group showed superior LCSS rates, suggesting that for the relatively younger age bracket, segmentectomy is less aggressive and might be used as an alternative to lobectomy and could yield superior long-term outcome than wedge resection.

The existing controversies mainly focus on surgical modalities among elderly patients with early-stage NSCLC based on the tumor size, while few studies have performed subgroup analyses according to the age and tumor size. Our study further confirmed that both tumor size and age at diagnosis should be considered when selecting surgical modalities. In elderly patients ≥76 years of age, a reduction in survival rate after lobectomy was observed for NSCLC tumors with a diameter ≤1 cm, while sublobar resection was non-inferior to lobectomy for tumors with a diameter >1–3 cm. However, in patients 70–75 years of age, segmentectomy yielded superior survival than lobectomy and wedge resection for tumors with a diameter >1–2 cm and lobectomy achieved superior LCSS than wedge resection did for lesions with diameter >2–3 cm, while no significant difference was found for those with a diameter ≤1 cm. To be cautious, high-quality evidence from RCTs is needed to verify our results. Currently, there were two prospective RCTs that have compared lobectomy and sublobar resection in early-stage NSCLC and a non-randomized trial (JCOG1211) that had assessed the efficacy of segmentectomy for lung cancers (28,29). These studies enrolled patients older than 18 years of age and a separate subset analysis for the elderly will be highly anticipated.

Marital status has been previously demonstrated as an independent prognostic factor in many cancer types (30-32). A recent study showed that marital status is an independent prognostic factor for cancer-specific survival in NSCLC patients, and patients who were married had better cancer-specific survival than patients who were unmarried (30). This finding is similar to that observed in our present study where marital status was identified as an independent risk factors for OS among patients in both the age groups of 70–75 years and ≥76 years, while no statistically significant difference was found in LCSS. Furthermore, marital status may play an important role when analyzing quality of life among older adults, suggesting that being married may offer a protective mechanism against depressive symptoms and therefore against mental illnesses during late adulthood (33). Thus, being married may have a positive effect on the OS of the elders with NSCLC while the effect on LCSS may require further investigations.

The SEER database is a robust source of cancer statistics with standardized reporting protocols and annually updated follow-up data. However, our study has some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, these data were retrospectively analyzed; although some advanced statistical methods were applied to balance the covariates among the study groups, some latent biases remained that were not adjusted. A separate subset analysis for elderly patients is anticipated in RCTs to provide prospective evidence (28). Second, the information was not comprehensive. Data regarding patient comorbidities and lung function status, stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT), treatment selection criteria, and recurrence rate were not recorded. Data regarding chemotherapy and target therapy were also not provided. However, these therapies were seldom performed in patients with early-stage NSCLC and this limitation could have negligible impact on survival. Another important limitation was that the SEER database did not include the information on thoracotomy and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Previous studies have found age and thoracotomy as independent predictors of morbidity in patients >70 years old (15). This important factor could not be analyzed in the SEER database and needs further investigation. Finally, this study focused on one primary NSCLC alone. Studies have reported that approximately 8% of patients with NSCLC have multiple lesions (34); thus, further studies are required to assess surgical modalities as a function of age and tumor size among elderly patients with multiple primary NSCLCs. Nonetheless, the results are striking and could affect future treatment planning.

In conclusion, among patients with stage IA NSCLC older than 76 years of age, decreasing survival rates after lobectomy were observed in those with a tumor diameter ≤1 cm; sublobar resection is considered as a viable alternative for these patients. For patients 70–75 years of age, segmentectomy led to better survival rates in those with NSCLC >1–2 cm in diameter, whereas lobectomy achieved superior survival rates than wedge resection did in patients with lesions >2–3 cm in diameter. Surgeons could select the modality of resection based on their own expertise and patient profile for NSCLC with diameter ≤1 cm.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-2221

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-2221). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The author is accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was based on a publicly available database; thus, it was exempted from the institutional review board approval. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70:7-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao X, Qian L, Luo Q, et al. Segmentectomy as a safe and equally effective surgical option under complete video-assisted thoracic surgery for patients of stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;8:116. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moyer VA, Force USPST. Screening for lung cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:330-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:615-22; discussion 622-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pettiford BL, Schuchert MJ, Santos R, et al. Role of sublobar resection (segmentectomy and wedge resection) in the surgical management of non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Surg Clin 2007;17:175-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schuchert MJ, Pettiford BL, Luketich JD, et al. Parenchymal-sparing resections: why, when, and how. Thorac Surg Clin 2008;18:93-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kilic A, Schuchert MJ, Pettiford BL, et al. Anatomic segmentectomy for stage I non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;87:1662-6; discussion 7-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zuin A, Andriolo LG, Marulli G, et al. Is lobectomy really more effective than sublobar resection in the surgical treatment of second primary lung cancer? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2013;44:e120-5; discussion e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Veluswamy RR, Ezer N, Mhango G, et al. Limited Resection Versus Lobectomy for Older Patients With Early-Stage Lung Cancer: Impact of Histology. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:3447-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shirvani SM, Jiang J, Chang JY, et al. Lobectomy, sublobar resection, and stereotactic ablative radiotherapy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancers in the elderly. JAMA Surg 2014;149:1244-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kates M, Swanson S, Wisnivesky JP. Survival following lobectomy and limited resection for the treatment of stage I non-small cell lung cancer <=1 cm in size: a review of SEER data. Chest 2011;139:491-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schuchert MJ, Kilic A, Pennathur A, et al. Oncologic outcomes after surgical resection of subcentimeter non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2011;91:1681-7; discussion 687-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Razi SS, John MM, Sainathan S, et al. Sublobar resection is equivalent to lobectomy for T1a non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. J Surg Res 2016;200:683-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Detterbeck FC, Chansky K, Groome P, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: Methodology and Validation Used in the Development of Proposals for Revision of the Stage Classification of NSCLC in the Forthcoming (Eighth) Edition of the TNM Classification of Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2016;11:1433-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry MF, Hanna J, Tong BC, et al. Risk factors for morbidity after lobectomy for lung cancer in elderly patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88:1093-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sihoe AD, Van Schil P. Non-small cell lung cancer: when to offer sublobar resection. Lung Cancer 2014;86:115-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGuire AL, Hopman WM, Petsikas D, et al. Outcomes: wedge resection versus lobectomy for non-small cell lung cancer at the Cancer Centre of Southeastern Ontario 1998-2009. Can J Surg 2013;56:E165-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chamogeorgakis T, Ieromonachos C, Georgiannakis E, et al. Does lobectomy achieve better survival and recurrence rates than limited pulmonary resection for T1N0M0 non-small cell lung cancer patients? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009;8:364-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Okada M, Koike T, Higashiyama M, et al. Radical sublobar resection for small-sized non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132:769-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keenan RJ, Landreneau RJ, Maley RH Jr, et al. Segmental resection spares pulmonary function in patients with stage I lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:228-33; discussion 228-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamura H, Kawasaki N, Taguchi M, et al. Survival following lobectomy vs limited resection for stage I lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2005;92:1033-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moon MH, Moon YK, Moon SW. Segmentectomy versus lobectomy in early non-small cell lung cancer of 2 cm or less in size: A population-based study. Respirology 2018;23:695-703. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dai C, Shen J, Ren Y, et al. Choice of Surgical Procedure for Patients With Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer</= 1 cm or > 1 to 2 cm Among Lobectomy, Segmentectomy, and Wedge Resection: A Population-Based Study. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3175-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ng CS, Zhao ZR, Lau RW. Tailored Therapy for Stage I Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:268-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mery CM, Pappas AN, Bueno R, et al. Similar long-term survival of elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with lobectomy or wedge resection within the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Chest 2005;128:237-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wisnivesky JP, Henschke CI, Swanson S, et al. Limited resection for the treatment of patients with stage IA lung cancer. Ann Surg 2010;251:550-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith CB, Swanson SJ, Mhango G, et al. Survival after segmentectomy and wedge resection in stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:73-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamura K, Saji H, Nakajima R, et al. A phase III randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for small-sized peripheral non-small cell lung cancer (JCOG0802/WJOG4607L). Jpn J Clin Oncol 2010;40:271-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aokage K, Saji H, Suzuki K, et al. A non-randomized confirmatory trial of segmentectomy for clinical T1N0 lung cancer with dominant ground glass opacity based on thin-section computed tomography (JCOG1211). Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;65:267-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen Z, Yin K, Zheng D, et al. Marital status independently predicts non-small cell lung cancer survival: a propensity-adjusted SEER database analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2020;146:67-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jatoi A, Novotny P, Cassivi S, et al. Does marital status impact survival and quality of life in patients with non-small cell lung cancer? Observations from the mayo clinic lung cancer cohort. Oncologist 2007;12:1456-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi Y, Chen W, Li C, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and prediction of cancer-specific survival in large cell lung cancer: a population-based study. J Thorac Dis 2020;12:2261-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez-Vega M, Esparza-Del Villar OA, Carrillo-Saucedo IC, et al. The Possible Protective Effect of Marital Status in Quality of Life Among Elders in a U.S.-Mexico Border City. Community Ment Health J 2018;54:480-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Battafarano RJ, Meyers BF, Guthrie TJ, et al. Surgical resection of multifocal non-small cell lung cancer is associated with prolonged survival. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:988-93; discussion 993-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]