Change in amount smoked and readiness to quit among patients undergoing lung cancer screening

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second-most prevalent cancer diagnosis, with 80% of cases attributable to cigarette smoking (1). Notably, lung cancer mortality can be reduced by 20–24% among patients engaged in low-dose CT lung cancer screening (LCS) and treatment of early-stage disease (2,3). Importantly, modeling studies suggest that even greater mortality reduction may occur when LCS is paired with smoking-cessation interventions (4,5). The time frame immediately surrounding LCS may serve as a “teachable moment” in which smokers have heightened awareness of health risks associated with smoking, increased motivation to stop smoking, and increased perceived risk for lung cancer (6). Indeed, LCS may provide an opportunity to leverage increased motivation to quit by offering cessation interventions, and some studies have shown that LCS is associated with abstinence or readiness to quit (7-10). However, as not all studies have found these associations (11-14), further study regarding smoking behavior in the LCS setting is warranted. The goal of the present study was to observe whether undergoing lung screening, along with receiving minimal cessation resources, impacted short-term smoking-related outcomes. We present this paper in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-3267).

Methods

Overview

Individuals who had registered to undergo LCS and who were currently smoking were invited to enroll in a randomized trial comparing a telephone-based smoking cessation intervention to usual care, described in a separate paper (15). For this secondary data analysis, we present data that were collected at two assessments that were conducted: (I) prior to the LCS exam, and (II) following the LCS exam and receipt of the screening results. Both assessments preceded trial randomization.

Participants

Eligibility criteria utilized NCCN guidelines (16) for LCS: (I) 50–80 years of age and (II) 20+ pack-year smoking history. Participants were current smokers who had registered for LCS at one of three screening programs [Georgetown University Medical Center (GUMC), Lahey Hospital and Medical Center (LHMC), and Hackensack University Medical Center (HUMC)]. Participants were excluded if they ultimately did not undergo LCS. Readiness to quit was not an eligibility criterion.

Procedure

Between November 2013 and March 2016, each LCS site invited smokers to learn more about this study when scheduling their LCS appointment. Once potential participants scheduled their LCS, GUMC interviewers called interested individuals to describe the study, obtain verbal consent, and conduct the pre-LCS telephone interview. Following the pre-LCS interview, all participants received the BecomeAnEx cessation booklet and a resource list, which included the BecomeAnEx website address, local cessation resources, the National Cancer Institute’s SmokefreeTXT address, and the link to the LIVESTRONG Cessation app (17-20).

Participants were consented as part of a randomized trial (15). The results presented in this paper do not concern the randomized trial, but only the data that were collected prior to randomization (trial registration number: NCT02267096). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Georgetown University Federal Wide Assurance number FWA00001080 and informed consent was taken from all individual participants. The IRB required verbal consent, followed by a mailed information sheet explaining the study procedures, participant rights, and potential risks, but did not require signed consent forms. Financial incentives were not provided for the completion of these two interviews.

Measures

Pre-LCS interview

We assessed past use of cessation interventions on a dichotomous yes/no scale. Future interest in cessation interventions was assessed on a 4-point scale including options for 1 “Yes, definitely”, 2 “Yes, possibly”, 3 “Probably not” and 4 “Definitely not”. Responses for future interest in cessation interventions were further collapsed into categories of “Yes, interested” (Item responses 1 and 2) and “Not interested” (Item responses 3 and 4) for analyses. Tobacco dependence was assessed using the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) (21), which ranges from 0 “Very low” to 10 “Very high” dependence. Cigarettes per day (CPD) was assessed using average number of cigarettes smoked per day on an ordinal scale of “Less than 1 per day”, “1 per day”, “2–5 per day”, “6–10 per day”, “11–20 per day”, “20 per day (1 pack)”, “21–40 per day (2 packs)”, “41–60 per day (3 packs)”, and “more than 3 packs per day”. Readiness to quit was assessed using the 10-item Contemplation Ladder, which ranges from “I have already begun to cut down/have a quit plan” to “I enjoy smoking so much I will never consider quitting” (22).

Post-LCS interview

We assessed utilization of the cessation resources provided (‘Yes, resource was used’ vs. ‘No, resource was not used’) and reassessed CPD and readiness to quit. LCS results were presented previously (14) and were not related to CPD or readiness to quit (data not shown).

Statistical analyses

Due to small cell sizes, we collapsed the outcomes into two categories: CPD (≤10 CPD vs. 11+ CPD); and readiness to quit (ready to quit in the next 30 days/already cut down vs. ready to quit in the next 6 months/not ready to quit). We conducted two McNemar binomial distribution tests to assess change in CPD and readiness to quit, from pre- to post-screening, to determine the percentage of participants who: (I) decreased (i.e., the post-LCS value of CPD or readiness to quit was lower than the pre-LCS value), (II) were unchanged (i.e., same category was endorsed at both assessments), or (III) increased (i.e., the post-LCS value was greater than the pre-LCS value). Significance levels were established at P<0.05. This pilot study was designed to evaluate feasibility and provide preliminary data for a subsequent trial. We conducted analyses using SPSS 25.0.

Results

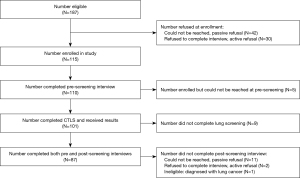

Participation rates

A total of 187 individuals met eligibility criteria and 115 (61.5%) enrolled (Figure 1) (15). The 72 eligible individuals who declined enrollment did not significantly differ from the 115 participants on age [t(185)=0.14, P=0.885] or gender [χ2(1, N=187)=2.59, P=0.108], but did report fewer pack-years [t(176.01)=−2.16, P=0.03]. Of those enrolled, 5 could not be reached at pre-LCS, 10 were ineligible for the post-LCS interview (9 did not undergo screening and 1 was diagnosed with lung cancer), and 13 declined the post-LCS interview. We include the 87/115 (75.7%) participants who completed both the pre- and post-LCS interviews to assess change over time in CPD and readiness to quit.

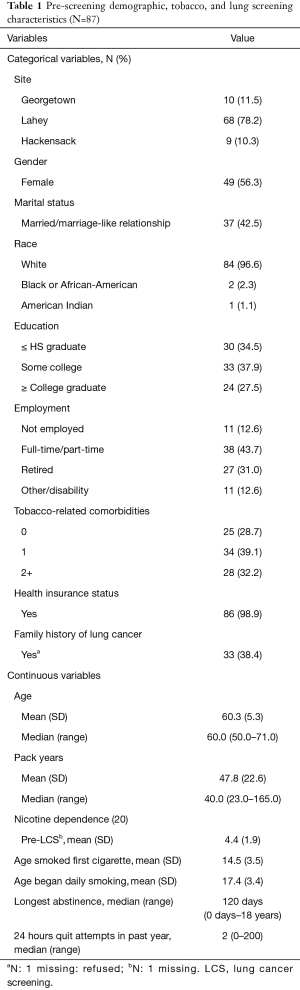

Pre-screening characteristics

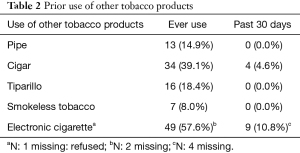

Participants were an average of 60.3 years old (SD =5.3), 56.3% were female, and the majority (96.6%) were white (Table 1). Regarding tobacco-related characteristics, the sample reported a moderate level of nicotine dependence (M=4.4, SD =1.9), a median of 40 pack-years, and very few had used tobacco or nicotine products other than cigarettes in the past 30 days (Table 2). Most participants (78%) were from LHMC due to that site’s higher screening volume.

Full table

Full table

Cessation strategies

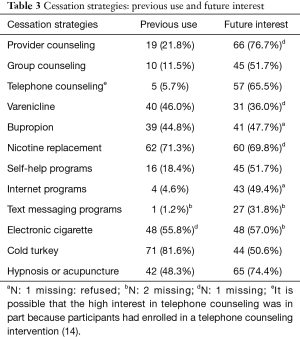

Cessation strategies used in previous quit attempts and those that participants were interested in using in the future are included in Table 3. Compared to the proportion who reported using cessation strategies previously, participants reported greater interest in using several evidence-based strategies. For example, although 81.6% had tried to quit ‘cold turkey’ previously, only 50.6% reported an interest in quitting ‘cold turkey’ in the future. Further, participants were very interested in receiving future counseling from a healthcare provider (76.7%) and in receiving NRT (69.8%). Regarding the minimal cessation resources we provided, participants reported low utilization (<5%), with the exception of the BecomeAnEx booklet (45.9%). We did not collect further details on participants’ use of the booklet (e.g., time spent reading or recall of the content).

Full table

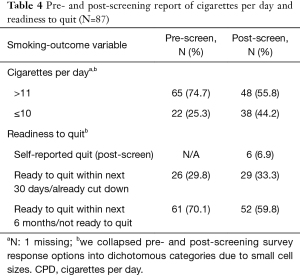

Longitudinal assessment of cigarettes per day and readiness to quit

The post-LCS telephone interview was completed a median of 12.5 days post-screening (mean =16 days, SD =10.9; range, 6–69 days). Table 4 presents CPD and readiness to quit at pre- and post-LCS. Regarding CPD, 25.3% reported smoking ≤10 CPD at the pre-LCS assessment, compared to 44.2% at post-LCS. Similarly, pre-LCS, 29.9% were ready to quit in the next 30 days, compared to the post-LCS assessment, in which 40.2% were either ready to quit in the next 30 days or self-reported having quit since the pre-LCS assessment.

Full table

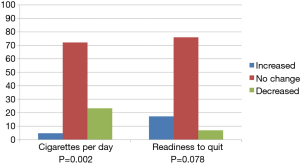

Figure 2 depicts the change over time in these variables, from pre- to post-screening, to assess the statistical significance of the percentage of participants who decreased, increased, or did not change. Participants were categorized as changed over time when they responded in a different category pre- to post-screen. The majority (72.1%) reported the same number of CPD at each assessment, while 23.3% reported smoking fewer CPD and 4.7% reported smoking more CPD (McNemar test, P=0.002) at the post-LCS assessment. Change in readiness to quit showed that 75.9% reported no change in their readiness, whereas 17.2% reported becoming more ready to quit, and 6.9% became less ready to quit (McNemar test, P=0.078).

Discussion

We assessed changes in cigarettes per day and readiness to quit among smokers undergoing LCS who also received free and low-cost evidence-based cessation resources. Although approximately three-quarters reported stable smoking-related outcomes from pre- to post-screening, almost one-quarter reported smoking fewer cigarettes and just over 15% became more ready to quit. This change was statistically significant for cigarettes per day and approached significance for readiness to quit. These results suggest that a portion of individuals made positive health changes, and also that a smaller portion became more inclined to continue smoking. These findings partially support previous studies that have shown the potential for a “teachable moment” and improved tobacco-related outcomes within the context of LCS (7-10). However, other studies do not support these findings (11-14), possibly due to a longer post-screening window in which assessments occurred, suggesting that motivation to reduce or stop smoking can quickly dissipate. Moreover, undergoing LCS in and of itself may not impact abstinence (23), which was also suggested by the low number of individuals who quit immediately following LCS in the present study. However, the changes in amount smoked and readiness to quit, along with the provision of cessation resources, may encourage progression toward quitting in this setting. The combination of LCS with the offer of minimal cessation resources reflects what occurs in many LCS clinical settings, which requires further assessment to understand the unique contributions of these individual factors, which cannot be teased apart in this study.

Although participants reported low usage of most of the cessation resources provided by the study, they indicated substantial interest in using other cessation methods, suggesting that LCS participants may be willing to engage in evidence-based and intensive interventions (e.g., counseling, nicotine replacement) when provided. Moreover, although a large proportion of participants had tried to quit ‘cold turkey’ previously, a far lower percentage reported an interest in using it in the future. Similarly, other than the FDA-approved medications, few had previously used cessation counseling or other evidence-based strategies, yet a majority expressed an interest in using several evidence-based strategies in the future. These results may suggest that evidence-based strategies were viewed more favorably at present than they were previously. Engaging all smokers in cessation interventions is of the utmost importance for maximizing the benefits of LCS.

Importantly, even among smokers who were enrolled in a cessation trial, a substantial proportion was not ready to quit, underscoring the need to determine tobacco treatment strategies that appeal to smokers in this setting. Similarly, as there was low utilization of the cessation resources we provided, additional encouragement is needed for smokers undergoing LCS to utilize available free and low-cost cessation resources, as well as to provide access to more intensive interventions.

These results should be interpreted in light of the methodological strengths and limitations. Regarding strengths, the assessments occurred proximal to the LCS exam, which provided an evaluation of the immediate smoking-related outcomes. These outcomes can set the stage for participant engagement in proactive cessation interventions. Second, combining the LCS exam with minimal cessation resources reflects the strategies that are typically utilized by LCS programs in order to meet the CMS mandate (24), thus adding to the real-world relevance of these findings. Third, the inclusion of smokers who are not ready to quit provided information on a group that is well-represented in LCS programs, but who may require greater effort in order to engage in cessation interventions. Fourth, although the sample size required collapsing the response categories of the smoking-related variables, a significant reduction in CPD and a marginally significant improvement in readiness to quit were detected. With a larger sample and continuous variables, more robust changes in smoking-related variables may be found. Methodological limitations included the limited diversity of the study sample, although this largely reflects those who are currently undergoing LCS (25). Additional limitations included the small sample size, the brief follow-up period, and the need to assess whether the results are generalizable to individuals undergoing LCS who are not enrolled in a cessation trial.

These results suggest that LCS and the provision of minimal, evidence-based cessation interventions may promote positive tobacco-related behaviors. These short-term changes in cigarettes per day and readiness to quit suggest that proactive and intensive cessation interventions will be needed to capitalize on the potential “teachable moment” of LCS. This is a period in which clinicians have an opportunity to educate patients on the harms of continued smoking in the context of receiving the LCS results, as well as to connect patients to cessation resources, regardless of their interest in quitting following LCS.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Paula Bellini for conducting the follow-up assessments and Susan Marx for her administrative assistance.

Funding: This work was supported by the Prevent Cancer Foundation and the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center’s National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA051008). The funders had no role in the interpretation of these results.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: We present the manuscript in accordance with the SURGE reporting checklist. Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-3267

Data Sharing statement: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-3267

Peer Review File: Available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-3267

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jtd-20-3267). EA served as a paid consultant for Intuitive Surgical for work unrelated to this research. SR received an honorarium for work unrelated to this research from LuCa National Training Network. CS and DA served as paid consultants on NCI grant 5R01CA207228-03 for work unrelated to the present research protocol, and from the Prevent Cancer Foundation grant (“Smoking Cessation in Lung Cancer Screening Participants: A Randomized Trial”) for the work presented in this manuscript. RN also served as a paid consultant on NCI grant 5R01CA207228-03 for work unrelated to the present research protocol. Author HH received payment and honoraria for speaking engagements unrelated to the present research protocol for Bristol-Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca. Author KT served as PI and received salary support and funds for a grant provided by the Prevent Cancer Foundation for the work presented in this manuscript, and also receives salary support as PI for NCI grant 5R01CA207228-03 for work unrelated to the present research protocol. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The results presented in this paper do not concern the randomized trial, but only the data that were collected prior to randomization (Trial Registration Number: NCT02267096). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of Georgetown University Federal Wide Assurance number FWA00001080 and informed consent was taken from all individual participants. The IRB required verbal consent, followed by a mailed information sheet explaining the study procedures, participant rights, and potential risks, but did not require signed consent forms.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- American Cancer Society. Lung cancer risk factors. 2020. Available online: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/non-small-cell-lung-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365:395-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- de Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med 2020;382:503-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Villanti AC, Jiang Y, Abrams DB, et al. A cost-utility analysis of lung cancer screening and the additional benefits of incorporating smoking cessation interventions. PLoS One 2013;8:e71379 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cao P, Jeon J, Levy DT, et al. Potential Impact of Cessation Interventions at the Point of Lung Cancer Screening on Lung Cancer and Overall Mortality in the United States. J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:1160-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McBride CM, Emmons KM, Lipkus IM. Understanding the potential of teachable moments: the case of smoking cessation. Health Educ Res 2003;18:156-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hahn EJ, Rayens MK, Hopenhayn C, et al. Perceived risk and interest in screening for lung cancer among current and former smokers. Res Nurs Health 2006;29:359-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor KL, Cox LS, Zincke N, et al. Lung cancer screening as a teachable moment for smoking cessation. Lung Cancer 2007;56:125-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tammemägi MC, Katki HA, Hocking WG, et al. Selection criteria for lung-cancer screening. N Engl J Med 2013;368:728-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brain K, Carter B, Lifford KJ, et al. Impact of low-dose CT screening on smoking cessation among high-risk participants in the UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial. Thorax 2017;72:912-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van der Aalst CM, van den Bergh KA, Willemsen MC, et al. Lung cancer screening and smoking abstinence: 2 year follow-up data from the Dutch-Belgian randomised controlled lung cancer screening trial. Thorax 2010;65:600-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park ER, Gareen IF, Jain A, et al. Examining whether lung screening changes risk perceptions: National Lung Screening Trial participants at 1-year follow-up. Cancer 2013;119:1306-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Park ER, Streck JM, Gareen IF, et al. A qualitative study of lung cancer risk perceptions and smoking beliefs among national lung screening trial participants. Nicotine Tob Res 2014;16:166-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Slatore CG, Baumann C, Pappas M, et al. Smoking behaviors among patients receiving computed tomography for lung cancer screening. Systematic review in support of the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:619-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Taylor KL, Hagerman CJ, Luta G, et al. Preliminary evaluation of a telephone-based smoking cessation intervention in the lung cancer screening setting: A randomized clinical trial. Lung Cancer 2017;108:242-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wood DE, Kazerooni EA, Baum SL, et al. Lung Cancer Screening, Version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018;16:412-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Legacy Foundation. Become an EX smoker, learn to quit smoking, stop smoking cigarettes. 2019. Available online: https://becomeanex.org

- American Legacy Foundation. Re-learn life without cigarettes EXTM. 2019. Available online: [no longer available online; available from the author].

- National Cancer Institute. SmokefreeTXT. 2018 Available online: https://smokefree.gov/smokefreetxt

- LIVESTRONG MyQuit Coach–dare to quit smoking APP. Available online: https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/livestrong-myquit-coach-dare/id383122255?mt=8

- Fagerström KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav 1978;3:235-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abrams DB, Niaura R. editors. The tobacco dependence treatment handbook: A guide to best practices. New York: Guilford Press, 2003.

- Minnix JA, Karam-Hage M, Blalock JA, et al. The importance of incorporating smoking cessation into lung cancer screening. Transl Lung Cancer Res 2018;7:272-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Decision Memo for Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT) (CAG-00439N). 2015. Available online: https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=274

- Sin MK. Lung cancer disparities and African-Americans. Public Health Nurs 2017;34:359-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]