|

Review Article

True Video -Assisted Thoracic Surgery for Early -Stage Non -Small Cell Lung Cancer

Christopher Q. Cao, Stine Munkholm-Larsen, Tristan D. Yan

From Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Royal Prince A lfred Hospital and the Baird Institute for Applied Heart and Lung Surgical, University of Sydney,

Sydney, NSW, Australia

Corresponding to: Dr Tristan D. Yan, BSc (Med) MBBS, PhD. University of Sydney,

Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, NSW, Australia.

Email: Traistan.yan@unsw.edu.au

|

|

Abstract

Since its inception, minimally invasive surgery has made a dramatic impact on all branches of surgery. Video-assisted thoracic surgery

(VATS) lobectomy for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was first described in the early 1990s and has since become popular

in a number of tertiary referral centers. Proponents of this relatively new procedure cite a number of potentially favorable perioperative outcomes, possibly due to reduced surgical trauma and stress. However, a significant proportion of the cardiothoracic community remains

skeptical, as there is still a paucity of robust clinical data on long-term survival and recurrence rates.

The definition of 'true' VATS has also been under scrutiny, with a number of previous studies being considered 'mini-thoracotomy lobectomy' rather than VATS lobectomy . We hereby examine the literature on true VATS lobectomy, with a particular focus on comparative studies that directly compared VATS lobectomy with conventional open lobectomy.

Key words

Video-assisted thoracic surgery; VATS; non-small cell lung cancer; lobectomy. J Thorac Dis 2009;1:34-38. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2009.12.01.003

|

|

Introduction

Since the first laparscopic cholecystectomy in the late 1980s,

minimally invasive surgery has revolutionised many branches of

surgery. After the first video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS)

lobectomy for early stage non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) was

simultaneously described by several institutions in the early 1990s

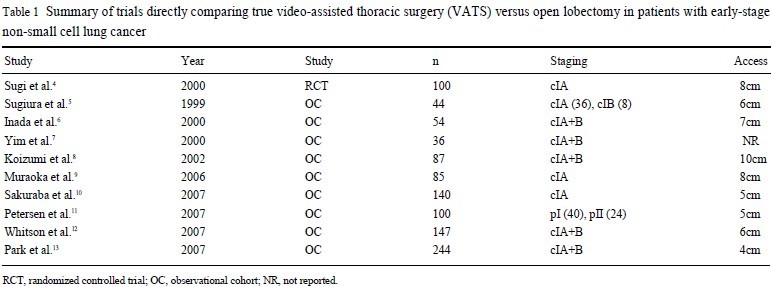

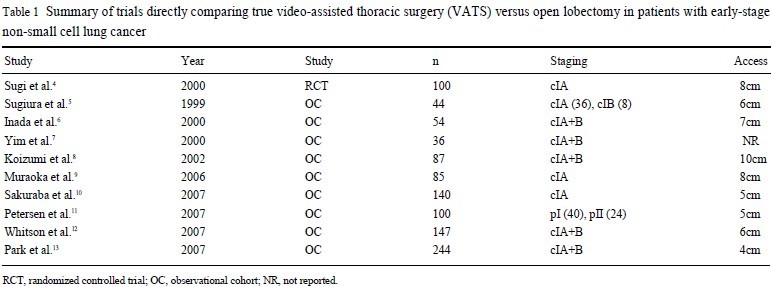

( 1- 3), several studies have demonstrated potential advantages associated with this new technique, possibly due to reduced trauma encountered during surgery ( Table 1) ( 4- 13). To date, two randomised

controlled trials (RCTs) have been completed, demonstrating the

safety and feasibility of VATS lobectomy compared to conventional open lobectomy ( 1, 4). Perhaps more importantly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggested that VATS lobectomy

does not differ significantly to open lobectomy in locoregional recurrence rate, and might even be associated with a reduced systemic recurrence rate and an improved overall 5-year mortality rate

( 14). From such reports, it is not surprising that the utility of VATS

lobectomy has steadily increased over the last decade, especially amongst high-volume centers ( 15).

Despite the encouraging results for VATS lobectomy, it has

been recognised that heterogeneous practice exists between institutions, including significant differences in patient selection, the

use of rib spreaders or retractors, and the length of access. Indeed, the very definition of VATS has been under scrutiny,

with some techniques being considered 'video-assisted mini-thoracotomy' rather than true non-rib spreading VATS lobectomy

( 4). In response, there has been a concerted effort by the International Society of Minimally Invasive Cardiothoracic Surgery

to standardize the definition of VATS ( 16). Based on these definitions, only a limited number of non-randomised comparative

studies have directly evaluated the true VATS approach for early stage lung cancers. We hereby review the current literature

on the safety and efficacy of VATS lobectomy, with a particular focus on the results of these non-randomized comparative

studies.

|

|

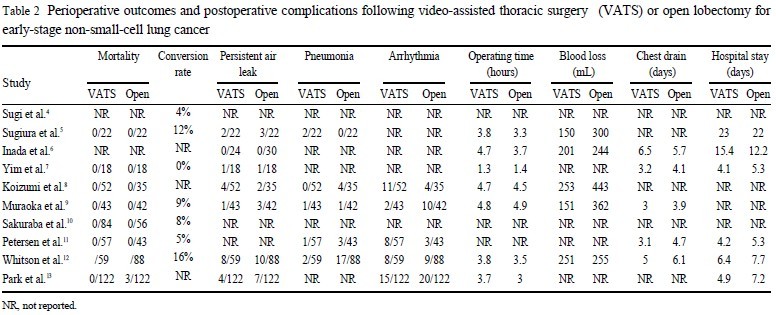

Safety

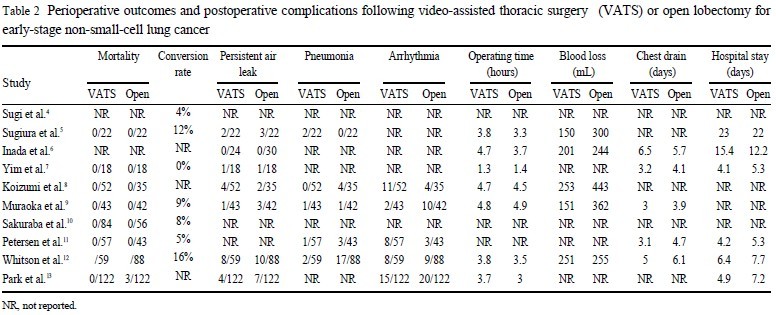

Perioperative mortality and morbidity

As with any new surgical technique, avoidable adverse outcomes might be expected to arise as a result of inexperience ( 17).

However, from the available data, VATS lobectomy has been

found to have an extremely low perioperative mortality rate. Indeed, no comparative studies have shown any significant difference

in postoperative mortality rates comparing VATS lobectomy to the

conventional open technique ( Table 2). This was further supported by McKenna et al. ( 18) in their large series of 1100 VATS

lobectomy patients, with an acceptable postoperative mortality rate

of 0.8%.

Complication rates have been shown to have a significant impact on quality of life, and can affect the length of stay as well as

physical and social function ( 19). Muraoka et al. ( 9) and Park et al.

( 13) both reported a significantly lower overall morbidity rate in

their VATS lobectomy group when compared to open lobectomy.

Possibly related to this, Petersen et al. ( 11) and Park et al. ( 9) also

reported a significantly shorter length of stay for patients in their

respective VATS lobectomy groups. Furthermore, McKenna et al.

( 18) reported a mean length of stay of less than 5 days in patients

who underwent VATS lobectomy ( 19).

Arrhythmia

Atrial fibrillation(AF) and other arrhythmias have been recognized to be associated with increases in morbidity and length of

stay for patients undergoing noncardiac thoracic surgery ( 20). Muraoka et al. ( 9) reported a significantly reduced incidence of post-operative arrhythmia in their VATS lobectomy patients (RR 0.20,

95% CI 0.05 to 0.84), but was unable to ascertain any specific reasons for this finding. Reduction in the incidence of cardiac overload secondary to blood transfusions and preservation of the cardiac branches of the vagal nerve during selective lymphadenectomy in the VATS lobectomy group have been postulated as possible

explanations. On the contrary, a larger study by Park et al. ( 13)

matched 122 patients in their VATS lobectomy group with an open

thoracotomy group, and found no significant difference in the incidence of postoperative AF. They suggested that the autonomic denervation and stress-mediated neurohumoral mechanisms resulting

from pulmonary resection, rather than incision-related effects, were

responsible for the pathogenesis of AF in these patients. This is

supported by a number of other studies, which found no significant

difference in the incidence of postoperative arrhythmias ( 8, 11, 12).

However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as definitions of arrhythmias, preventative strategies and monitoring techniques differ between institutions.

Pneumonia

Whitson et al. ( 12) found significantly fewer cases of postoperative pneumonia in their VATS lobectomy arm (RR 0.18, 95% CI

0.04 to 0.73), and suggested that this may be due to a combination

of reduced postoperative inflammation, less pain, and fewer secretions.

Although a number of other studies did not find any significant difference in the incidence of pneumonia between VATS and

open lobectomy groups ( 8, 11, 13), Muraoka et al. ( 9) did report a

significant difference in sputum retention (p=0.026), and attributed

this to reduced postoperative pain in their VATS lobectomy patients, which was also credited for a reduction in other respiratory

complications, including atelectasis and ARDS.

Pain

Postoperative pain management has a significant effect on patient recovery and is essential for optimization of postoperative

care ( 21). A number of studies have shown that minimally invasive

techniques are associated with reduced postoperative pain ( 22, 23).

Yim et al. ( 7) and Maraoka et al. ( 9) both reported reduced levels

of postoperative pain for patients in their VATS lobectomy groups.

Despite a relatively small number of patients, Yim et al. ( 7) reported a significantly reduced amount of parenteral narcotics required

by patients in their VATS lobectomy arm. Similarly, Muraoka et

al. ( 9) evaluated postoperative pain by means of epidural tube duration, additional analgesic requirement, and visual analogue pain

scale, and reported significantly less postoperative pain in their

VATS lobectomy group. In addition, they commented that all patients who underwent VATS lobectomy in their study were able to

stand up beside their bed in the intensive care unit on postoperative

day 1. In contrast, patients in the open thoracotomy group were not

able to achieve this, even though both groups received the same

pain control regimen by continuous epidural infusion of bupivacine. Muraoka further commented that this finding was particularly important for an earlier recovery of activities of daily living.

Inflammatory markers

To support the hypothesis that VATS lobectomy causes less

surgical trauma and stress to patients, a number of studies have

compared postoperative serum markers of inflammation between

the VATS and open groups. Yim et al. ( 7) found significantly lower levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in patients in their VATS lobectomy arm

in the first 48 hours postoperatively. However, these patients were

also found to have significantly lower levels of IL-10, an anti-in-flammatory cytokine. From these results, Yim suggested that open

thoracotomy may be associated with an increased imbalance of

pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators due to an increased extent of inflammatory injury. Muraoka et al. ( 9) recorded

the maximum levels of white cell count and C-reactive protein

postoperatively, and found significantly lower levels inpatients

who underwent VATS lobectomy. However, it should be noted

that they did not find significantly lower IL-6 and IL-8 levels on

the first postoperative day, as reported by Yim et al.

Conversion

Conversion rates of VATS lobectomy to open lobectomy varied

greatly between different institutions, ranging from 0% to 16%

( 4- 13). A contentious point is the grouping of patients who had to

convert to open thoracotomy after a failed VATS lobectomy. In

their RCT, Kirby et al. ( 1) excluded 3 patients from their VATS

lobectomy arm after encountering difficulty in safely dissecting either the interlobar

pulmonary artery or incomplete fissures. Another RCT conducted by Sugi et al.

( 4) initially randomized 50 patients to each arm of their study, but transferred two patients from

the VATS lobectomy group to the open thoractomy group for statistical analysis after they experienced intraoperative bleeding and

required conversion. It has been argued that this transfer was unfair,

as these two patients suffered a complication of VATS requiring an open procedure and should be included in the VATS group

( 4).

Proponents of VATS lobectomy emphasize a number of other

potential benefits associated with the minimally invasive technique, including reduced intraoperative blood loss ( 5, 9), shortened

chest tube duration ( 9), and length of stay ( 11). In addition to a potential improvement in the quality of life, these factors may also be

of significant value in clinical management. For example, Petersen

et al. ( 11) found that patients in their VATS lobectomy group were

more compliant with their adjuvant chemotherapy regimens, and a

higher proportion of patients were able to tolerate a higher dose of

chemotherapy agents. This was possibly related to their reduced

postoperative complications and quicker recovery from their VATS

surgery.

|

|

Efficacy

Although there is increasing evidence that suggests VATS

lobectomy can be associated with short-term outcomes such as reduced morbidity,

less postoperative pain and quickened recovery,

the ultimate question remains to be whether these parameters can

be achieved without compromising the long-term oncologic efficacy

in the form of survival and locoregional and systemic recurrence

rates.

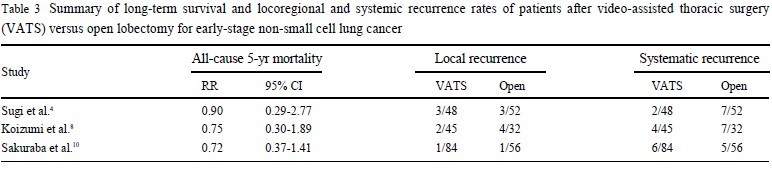

A number of comparative studies found no significant differences in either locoregional or systemic

recurrence ( 4, 8, 10). The results of these studies can be seen in Table 3.

A recent meta-analysis( 14) actually reported a reduced systemic recurrence rate (p=0.03) for VATS lobectomy when compared to open surgery.

Similar to the findings on locoregional and systemic recurrence

rates, all-cause 5-year mortality rates have been found to be

non-significant between VATS lobectomy and open lobectomy

groups in a number of studies ( 4, 8, 10). Indeed, a meta-analysis

( 14) indicated a more favourable 5-year mortality rate for VATS

lobectomy patients (p=0.04). |

|

Discussion

Not long after the first reports of VATS lobectomy, Kirby et al.

( 1) conducted the first RCT to assess the safety and potential

benefits associated with this new technique. This trial included 61 patients with clinical

stage I NSCLC who underwent VATS lobectomy or muscle sparing thoracotomy, and found significantly lower

postoperative complication rates in the VATS lobectomy group

(6% vs 16%), but not a significant decrease in the duration of

chest tube drainage, blood loss, length of hospital stay, or postoperative pain.

It should be noted that rib spreading was not avoided in

all patients in the VATS group and mini-thoracotomy was performed for an unknown number of patients. The second RCT by

Sugi et al. ( 4) randomized 100 patients with clinical stage I/A lung

cancer for VATS lobectomy and mediastinal lymph node dissection or posterolateral open thoracotomy.

This study found no significant differences in recurrence and survival rates, with overall

5-year survival rates of 90% and 85% in the VATS and open

groups, respectively. Although the results from these reports have

been encouraging, both RCTs have been scrutinized for a number

of reasons. Firstly, the precise definition of VATS lobectomy has

been questioned by some surgeons ( 4). The blurry line between

'true' VATS lobectomy and mini-thoracotomy was addressed by

the multi-institutional study conducted by the Cancer and

Leukemia Group B (CALGB) 39802 prospective trial ( 24), which

chose to define VATS lobectomy as a true anatomic lobectomy

with individual ligation of lobar vessels and bronchus, as well as

hilar lymph node dissection or sampling, without the use of retractors or rib spreading.

Another criticism encountered by both RCTs

has been the designation of patients into study arms for statistical

analysis, as both studies excluded or transferred patients from their

respective VATS lobectomy groups after a conversion to open thoracotomy was performed.

In addition to the RCTs, a number of non-randomized, comparative studies have been

conducted to assess a number of parameters between VATS and open lobectomy surgeries ( 4- 13). These

studies have indicated a number of potential advantages associated

with the VATS procedure, including reduced arrhythmias, pneumonia,

intraoperative bleeding, posteroperative pain, inflammatory

response, chest drain duration, length of stay, and overall complications.

Overall, the current literature suggests that VATS lobectomy performed in

qualified centres is a valid alternative to open

surgery for early-stage NSCLC, and can be associated with reduced

morbidity, without any evidence of compromise to overall survival

or recurrence rates. However, robust clinical data is still lacking for

a direct comparison between true VATS lobectomy and conventional open lobectomy, and it remains difficult to ascertain the benefits

associated with this relatively new procedure without further

studies involving appropriately defined patients. Future studies

should focus on recruiting a larger number of patients, preferably

in the form of well designed RCTs.

|

|

References

- Kirby TJ, Rice TW. Thoracoscopic lobectomy. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:784-6.

[LinkOut]

- Lewis RJ. The role of video-assisted thoracic surgery for cancer of the lung: wedge resection to lobectomy by simultaneous stapling. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;56:762-8.

[LinkOut]

- Walker WS, Carnochan, FM, Pugh GC. Thoracoscopic pulmonary lobectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993;106:1111-7. [LinkOut]

- Sugi K, Kaneda Y, Esato K. Video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy achieves a satisfactory long-term prognosis in patients with clinical stage IA lung cancer.World J Surg 2000;24:27-30.

[LinkOut]

- Sugiura H, Morikawa T, Kaji M, Sasamura Y, Kondo S, Katoh H. Long-term benefits for the quality of life after video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy in patients with lung cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 1999;9:403-8.

[LinkOut]

- Inada K, Shirakusa T, Yoshinaga Y, Yoneda S, Shiraishi T, Okabayashi K, et al. The role of video-assisted thoracic surgery for the treatment of lung cancer: lung lobectomy by thoracoscopy versus the standard thoracotomy approach. Int Surg 2000;85:6-12.[LinkOut]

- Yim AP, Wan S, Lee TW, Arifi AA. VATS lobectomy reduces cytokine responses compared with conventional surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2000;70:243-7.

[LinkOut]

- Koizumi K, Haraguchi S, Hirata T, Hirai K, Mikami I, Fukushima M, et al. Video-assisted lobectomy in elderly lung cancer patients. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2002;50:15-22.

[LinkOut]

- Muraoka M, Oka T, Akamine S, Tagawa T, Nakamura A, Hashizume S, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy reduces themorbidity after surgery for stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Jpn J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;54:49-55.

[LinkOut]

- Sakuraba M, Miyamoto H, Oh S, Shiomi K, Sonobe S, Takahashi N, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy vs. conventional lobectomy via open thoracotomy in patients with clinical stage IA non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2007;6:614-7.

[LinkOut]

- Petersen RP, Pham D, Burfeind WR, Hanish SI, Toloza EM, Harpole DH Jr, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy facilitates the delivery of chemotherapy after resection for lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1245-9.

[LinkOut]

- Whitson BA, Andrade RS, Boettcher A, Bardales R, Kratzke RA, Dahlberg PS, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery is more favorable than thoracotomy for resection of clinical stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;83:1965-70.

[LinkOut]

- Park BJ, Zhang H, Rusch VW, Amar D. Video-assisted thoracic surgery does not reduce the incidence of postoperative atrial fibrillation after pulmonary lobectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:775-9.

[LinkOut]

- Yan TD, Black D, Bannon PG, McCaughan BC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials on safety and efficacy of video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy for early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2553-62.

[LinkOut]

- Farjah F, Wood DE, Mulligan MS, Krishnadasan B, Heagerty PJ, Symons RG, et al. Safety and efficacy of video-assisted versus conventional lung resection for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;137:1415-21.

[LinkOut]

- Downey R, Cheng D, Kernstine K, Stanbridge R, Shennib H, Wolf R, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery in lung cancer resection: a consensus statement of the International Society of Minimally Invasive Cardiothoracic Surgery (ISMICS) 2007. Innov: Technol Tech Cariothorac Vasc Surg 2007;2:293-302.

[LinkOut]

- Krähenbühl L, Sclabas G, Wente MN, Schäfer M, Schlumpf R, Büchler MW. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of biliary tract injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Switzerland. World J Surg 2001;25:1325-30.

[LinkOut]

- McKenna RJ Jr, Houck W, Fuller CB. Video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy: experience with 1,100 cases. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:421-5.

[LinkOut]

- Avery KN, Metcalfe C, Nicklin J, Barham CP, Alderson D, Donovan JL, et al. Satisfaction with care: an independent outcome measure in surgical oncology.Ann Surg Oncol 2006;13:764-5.

LinkOut]

- Passman RS, Gingold DS, Amar D, Lloyd-Jones D, Bennett CL, Zhang H, et al. Prediction rule for atrial fibrillation after major noncardiac thoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:1698-703.

[LinkOut]

- Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS, Gan TJ. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg 2003;97:534-40.

[LinkOut]

- Darzi SA, Munz Y. The impact of minimally invasive surgical techniques. Annu Rev Med 2004;55:223-37.

[LinkOut]

- Massard G, Thomas P, Wihlm J. Minimally invasive management for first and recurrent pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;66:592-9.

[LinkOut]

- Swanson SJ, Herndon JE 2nd, D'Amico TA, Demmy TL, McKenna RJ Jr, Green MR, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery lobectomy: Report of CALGB 39802-a prospective, multi-institution feasibility study. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:4993-7.

[LinkOut]

Cite this article as: Cao CQ, Munkholm-Larsen S, TD. True Video -Assisted Thoracic Surgery for Early -Stage Non -Small Cell Lung Cancer. J Thorac Dis 2009;1:34-38. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2009.12.01.003

|