Voluntary pulmonary function screening with GOLD standard: an effective and simple approach to detect lung obstruction

Introduction

Lung obstruction is characterized by a decrease in airflow and shortness of breath. In adults without a diagnosis of asthma the cause of about 90% of airflow limitation is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) due to cigarette smoking (1). Nearly 15% of U.S. adults aged 40-79 had any lung obstruction in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (2). Data of adults aged 40 or older from seven provinces in China showed the overall prevalence of COPD was 8.2% (men, 12.4%; women, 5.1%) (3). Another survey found 35.3% of COPD were asymptomatic in China (4). It is estimated that COPD will be the third leading cause of death by 2020 (5-8).

However, undiagnosed airflow limitation (airway obstruction) is common in the general population and is associated with impaired health and functional status (9,10). Potentially, most lung obstruction can be prevented by reduction of the main causal risk factor (cigarette smoking) (11,12) or by screening and early detection of lung obstruction, which generally entails spirometry, targeting of individual symptoms, or a combination.

Early screening in community may detect asymptomatic and symptomatic COPD by prebronchodilator spirometry. For example, portable spirometers were provided freely by volunteers during European Respiratory Society (ERS) Congresses in 2004-2009. The percentage of investigated subjects had lung obstruction was 12.4% according to the lower limit of normal (LLN) standard and 20.3% according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) standard (13). Voluntary public lung screening program as one mechanism for early detection makes more people that held some concern about their health status participate in the public testing. It is such “self” selection that may actually benefit the screening for lung obstruction. There has been no formal study of the effectiveness of voluntary public screening programs in China. In addition, there is increasing scientific interest about the diagnostic standard for lung obstruction. To date, no consensus exists on how, when, and where public screening with LLN criterion or GOLD criterion should be implemented. Therefore, the objective of this study is to investigate the effectiveness of a voluntary public lung function screening program and the agreement between two definitions in voluntary public screening in Xi’an China.

Methods

Subjects

Xi’an is divided into four districts according to administrative region: North, East, South, and West. Two communities in each district were selected randomly for voluntary public screening. This was usually performed in a public space of the community to give local citizens the opportunity to have their lung function tested for free. Extensive leaflet coverage leading up to the event helped to attract a large number of people. However, age of the participants for screening was more than 18, residency in their current community for at least two years. Participants provided informed consent and completed a heath questionnaire and spirometric evaluation between July and August 2012. Patients that self-reported chronic lung disease on the health survey were excluded from the analysis. This study was approved by the ethic committee from the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Medical University (FAHXMU).

Design of questionnaire

Participants filled out a modified ATS-DLD-78 Questionnaire (14) by self-administered way. Survey content includes age, gender, height, weight, medical history, chronic lung disease history (defined as interstitial lung disease, COPD, asthma, chronic bronchitis, and bronchiectasis), and smoking status.

Pulmonary function test (PFT)

Forced vital capacity (FVC), and force expiratory volume in first second (FEV1) were measured by portable Spirometer (Spirobank G, Medical International Research, Rome, Italy) without ultrasound and oximetry. Participants underwent three FVC maneuvers without bronchodilator, and the maneuver with the best FEV1 was retained. Efforts that were incomplete or in which the patient coughed were excluded. PFTs were performed by staff certified in PFT administration according to ATS/ERS task force (15).

Definition of lung obstruction

GOLD standard: FVC can be normal or reduced-usually to a lesser degree than FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio below 0.7 (16). All predicted values were based off the Knutson prediction model.

LLN standard: a FEV1 to FVC ratio less than LLN (17). LLN can be calculated by GLI2012 desktop software produced by the Global Function Initiative and a Task Force of the ERS (www.lungfunction.org). All predicted values were based off the North East Asian prediction model.

Statistic method

The data was analyzed using JMP™ version 10 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and GraphPad Prism™ Version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was used for the analysis of categorical variables. The ANOVA test was utilized to compare measurement variables. Kappa test was used to compare the agreement between GOLD and LLN criterion. Results are reported as mean ± SEM, P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

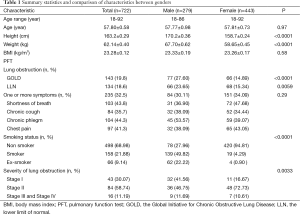

A total of 803 volunteers participated in this study and 33 subjects were excluded because PFTs did not meet the requirements. Of 770 volunteers, 722 (93.8%) did not self-report chronic lung disease and were analyzed. For the analyzed cohort, the mean ± SEM height was 163.2±0.29 cm, and the mean ± SEM age was 57.80±0.58 years. Of these participants, 143 subjects (19.8%) were diagnosed by GOLD standard and 134 subjects (18.6%) had obstruction with LLN definition. A greater percent of males than females had lung obstruction with GOLD or LLN standard (P<0.01). A total of 235 subjects (32.5%) had one or more symptoms including shortness of breath, chronic cough, chronic phlegm and chest pain. The overall prevalence of smoke including smoker and ex-smoker was 30% and the difference between males and females was significant (P<0.0001) (Table 1).

Full table

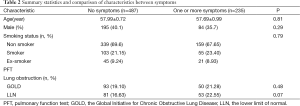

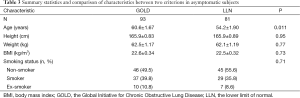

All the subjects were utilized to analyze whether the prevalence of lung obstruction was different between symptoms. No difference among age, gender and smoking status was found. A border line difference was found between the LLN value of symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects (P=0.07). GOLD definition can identify more subjects without symptoms (19.1%) with respect to LLN (Table 2). The asymptomatic subjects who lung obstruction were further analyzed. The participants diagnosed by LLN were younger than one by GOLD (P=0.011) in Table 3

Full table

Full table

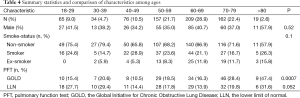

Advanced age is related with lung obstruction. Thus, 722 subjects were divided into seven groups according to decades of age in Table 4. A total of 623 participants (86.29%) were older than 40 years. The difference of smoking status among the age groups was not significant. GOLD definition can detect more elder subjects had lung obstruction, compared with young people, the difference is significant (P=0.0007). The border line difference of lung obstruction identified by LLN criterion in all age groups was found (P=0.052).

Full table

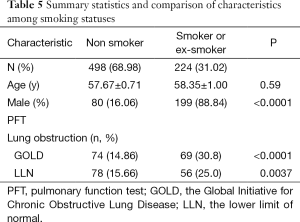

The subjects were utilized to analyze whether the prevalence of lung obstruction was different between smoking status in Table 5. A greater percent of smokers or ex-smokers than non-smokers had lung obstruction whatever GOLD or LLN standard was implemented (P<0.01).

Full table

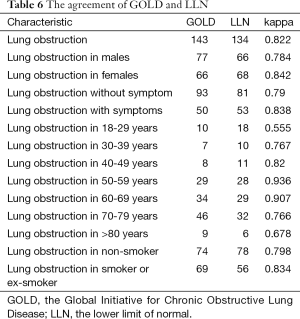

The kappa test was used to analyze the agreement between GOLD and LLN method in different subgroups in Table 6. The overall agreement between the two methods was good: the kappa estimate was 0.822. The agreement in females than males was better: the kappa estimate was 0.842, 0.784 respectively. The agreement in subjects with symptoms than without symptoms was better: the kappa estimate was 0.838, 0.79 respectively. The agreement in smoker or ex-smoker was better than non-smoker: the kappa estimate was 0.834, 0.798 respectively. The agreement in subjects aged 40-49, 50-59 and 60-69 years were good: the kappa estimate was 0.82, 0.936 and 0.907 respectively. The agreement in subjects aged 18-29 was inferior: the kappa estimate was only 0.555 (Figure 1).

Full table

Discussion

Chronic obstructive lung diseases are a substantial burden in China. Early detection and diagnosis may alter the course and prognosis associated with lung disease. The present study showed whatever GOLD or LLN criterion was adopted, nearly one-fifth of adults voluntarily participated in a public screening program in Xi’an had lung obstruction and about two-third of participants identified by lung obstruction were asymptomatic. LLN criterion could identify more participants aged 18-39 had lung obstruction. A greater percent of smokers or ex-smokers than non-smokers had lung obstruction. The overall agreement between GOLD and LLN method was good, especially in subjects aged 40-69 years. Therefore, our finding suggests the agreement to diagnose the lung obstruction in subjects aged 40-69 between GOLD and LLN method was good. Using a public lung function screening program in China with GOLD standard may be an effective and simple approach to ensuring high yield detection of lung obstruction in subjects aged 40-69.

A meta-analysis showed the overall prevalence of COPD in the general population was estimated to be about 1% across all ages, rising steeply to 8-10% or higher in individuals aged 40 years or older (18), which is consistent with Zhong’ Survey. The population studies (19-22) showed that underdiagnosis of COPD was high and independent of overall prevalence, ranging from 72% in Spain to 93% in Uruguay. Our results indicated nearly 20% of participants were identified by lung obstruction in Xi’an. These subjects may avoid progressive decline in lung function after they obtained spirometry results and stopped risk factor exposure.

Clinically some patients have even presented with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure, but they never provide any history of chronic respiratory symptoms and are diagnosed as COPD, which is asymptomatic COPD. Two nationwide surveys were conducted in Korea and United States (23,24), which showed 36.9% and 16.2% of the COPD patients reported no respiratory symptoms. Our results demonstrated about 60% of subjects identified by lung obstruction were asymptomatic, which further proved voluntary screening program was an effective method.

The high rate of undiagnosed and asymptomatic lung obstruction in our population is likely multifactorial. Prebronchodilator FEV1 in our study was used because we performed PFT in the community and it will produce the problem for participants to inhale the bronchodilator. GOLD criterion is designated for postbronchodilator FEV1. Thus, it seems that the subjects had lung obstruction belong to either bronchial asthma or COPD or both of them (asthma COPD overlap syndrome). In addition, though reproducibility and acceptability of the maneuver can be guaranteed by training the investigators, error is not evitable and causes the bias.

Spirometry has been the routine diagnostic procedure of choice recommended to diagnose lung obstruction (11). However, the degree of obstruction that establishes the diagnosis is still under debate (25). The GOLD defined lung obstruction as a fixed ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second and forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC ratio) of less than 0.70 (16). This definition is widely accepted, mainly because of its practicability. Since the FEV1 value decreases more quickly with age than the FVC, the GOLD definition tends to over-diagnose lung obstruction in the elderly (26,27). Therefore, some authors suggested using the LLN procedure to diagnose (25). The LLN is based on age-stratified pre-bronchodilator cut-off values of the FEV1/ FVC ratio, and a value below the lower fifth percentile of an aged-matched healthy reference group is considered abnormal and consistent with a diagnosis of lung obstruction. However, LLN spirometric threshold failed to identify a number of patients with significant pulmonary pathology and respiratory morbidity according to the findings of Surya and colleagues (28). Our results demonstrated that the overall agreement between 2 methods was good, especially in the subjects aged 40-69 years. Thus, both two diagnostic methods in subjects aged 40-69 years are efficient, but it is much simple to implement GOLD standard for a voluntary screening program. Furthermore, we anticipate it is more sensitive as a screening diagnostic standard, but LLN definitions can under-diagnosed COPD in elderly patients with respect to an expert panel diagnosis (29). Thus, GOLD standard was preferred to voluntarily screen in Xi’an, China.

Conclusions

Voluntary public lung function screening program with GOLD standard may be a simple and effective approach to ensuring high yield detection of lung obstruction in subjects aged 40-69.

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to the study participants and research personnel for their involvement in the study and appreciate the advice from Scanlon, Paul D and Hinds, Richard F.

Funding: Supported by the Education Department of Shaanxi Provincial Government (11JK0707).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Enright PL, Kaminsky DA. Strategies for screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Care 2003;48:1194-201; discussion 1201-3. [PubMed]

- Tilert T, Paulose-Ram R, Brody DJ. Lung Obstruction Among Adults Aged 40-79: United States, 2007-2012. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db180.htm

- Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:753-60. [PubMed]

- Lu M, Yao WZ, Zhong NS, et al. Asymptomatic patients of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:1494-9. [PubMed]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1498-504. [PubMed]

- Lopez AD, Shibuya K, Rao C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: current burden and future projections. Eur Respir J 2006;27:397-412. [PubMed]

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Black R, et al. Global burden of disease 2005: call for collaborators. Lancet 2007;370:109-10. [PubMed]

- Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442. [PubMed]

- O’Hagan J. Prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a challenge for the health professions. N Z Med J 1996;109:1-2. [PubMed]

- Coultas DB, Mapel D, Gagnon R, et al. The health impact of undiagnosed airflow obstruction in a national sample of United States adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:372-7. [PubMed]

- Rabe KF, Hurd S, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:532-55. [PubMed]

- Bize R, Burnand B, Mueller Y, et al. Biomedical risk assessment as an aid for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:CD004705. [PubMed]

- Maio S, Sherrill DL, MacNee W, et al. The European Respiratory Society spirometry tent: a unique form of screening for airway obstruction. Eur Respir J 2012;39:1458-67. [PubMed]

- Ferris BG. Epidemiology Standardization Project (American Thoracic Society). Am Rev Respir Dis 1978;118:1-120. [PubMed]

- Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319-38. [PubMed]

- Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1256-76. [PubMed]

- Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J 2005;26:948-68. [PubMed]

- Halbert RJ, Natoli JL, Gano A, et al. Global burden of COPD: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2006;28:523-32. [PubMed]

- Menezes AM, Perez-Padilla R, Jardim JR, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in five Latin American cities (the PLATINO study): a prevalence study. Lancet 2005;366:1875-81. [PubMed]

- Peña VS, Miravitlles M, Gabriel R, et al. Geographic variations in prevalence and underdiagnosis of COPD: results of the IBERPOC multicentre epidemiological study. Chest 2000;118:981-9. [PubMed]

- Bednarek M, Maciejewski J, Wozniak M, et al. Prevalence, severity and underdiagnosis of COPD in the primary care setting. Thorax 2008;63:402-7. [PubMed]

- Lundbäck B, Lindberg A, Lindström M, et al. Not 15 but 50% of smokers develop COPD?--Report from the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden Studies. Respir Med 2003;97:115-22. [PubMed]

- Chang JH, Lee JH, Kim MK, et al. Determinants of respiratory symptom development in patients with chronic airflow obstruction. Respir Med 2006;100:2170-6. [PubMed]

- Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, et al. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1683-9. [PubMed]

- Swanney MP, Ruppel G, Enright PL, et al. Using the lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio reduces the misclassification of airway obstruction. Thorax 2008;63:1046-51. [PubMed]

- Hardie JA, Buist AS, Vollmer WM, et al. Risk of over-diagnosis of COPD in asymptomatic elderly never-smokers. Eur Respir J 2002;20:1117-22. [PubMed]

- Celli BR, Halbert RJ, Isonaka S, et al. Population impact of different definitions of airway obstruction. Eur Respir J 2003;22:268-73. [PubMed]

- Bhatt SP, Sieren JC, Dransfield MT, et al. Comparison of spirometric thresholds in diagnosing smoking-related airflow obstruction. Thorax 2014;69:409-14. [PubMed]

- Güder G, Brenner S, Angermann CE, et al. GOLD or lower limit of normal definition? A comparison with expert-based diagnosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a prospective cohort-study Respir Res 2012;13:13. [PubMed]