In 1970s the risk of fatal airway obstruction or cardiovascular

collapse during induction of anesthesia in patients with large anterior mediastinal masses was first time recognized (

1). Hypoxia,

carbon dioxide accumulation, asphyxia, cardiopulmonary arrest,

cerebral edema or hemorrhage can occur due to failed intubation or

dysfunction of ventilation following intubation. This situation can

be fatal. It will require at least 5-10 min (much more time spent in

our patient) to cannulate and establish adequate circulation and

oxygenation (

4), even with a primed pump and a prepared team.

CPB via femoral vessels before induction of anesthesia is a good

option. It can allow gas exchange, avoidinghypoxia and hypercapnea which can lead to cardiac arrest and safeguard smooth intubation. Meanwhile, it can give good surgical access for the mass operations. Though thyroidectomy can safely be performed via cervical incisions and without the CPB support in 94% to 98% substernal goiters (

5), it’s difficult to differentiate definitely the extent of

mass preoperatively. Median sternotomy may be indicated following the cervical exploration, the management of which might have

required CPB support. In this patient the establishment of CPB was

necessary mainly for respiratory, not hemodynamic reasons confirmed intraoperatively. Regarding CPB (esp. shortened duration)

related complications; they can be minimized where cardiac

surgery is routinely performed. CPB is now considered a safe and

acceptable everyday clinical tool.

We finally chose to cannulate the femoral vessels under local

anesthesia and to keep the circuit ready to initiate CPB followed by

bronchoscope guided tracheal intubation based on the patient’s

baseline and consensus between medical staffs and patient.

Traumatic intubation may precipitate postoperative laryngeal

edema when blind intubation is usually performed even by a senior

anaesthetist (

6). In the absence of a 2mm in outer diameter flexible

fibreoptic bronchoscope in our hospital, we used a 5.5mm alterna

tive to guide the tracheal intubation after the induction of anesthesia. Flexible bronchoscopy can be useful intraoperatively to exclude an invasion of the tracheal wall by a neoplasm and evaluate

the tracheal compression as well as the risk of tracheomalacia.

More importantly it can help to guide the endotracheal cannula

passing beyond the site of obstruction and the distal margins of the

stenotic process could be visualized (

6). Our patient’s tracheal mucosa was smooth. The performer turned the bronchoscope gently

and slowly which slipped beyond the obstruction smoothly. The

time spent may be less than what it was because several colleagues

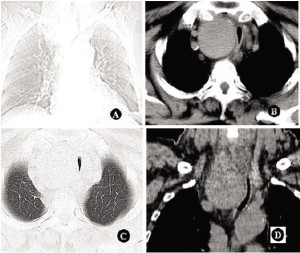

browsed what the bronchoscope displayed in turn. Hence, the apparently narrow trachea easily distended and did not impair passage of the tube into the trachea opposed to being predicted preoperatively, a finding ever noted by Shen and Kebebew and was confirmed in our study (

7). In a recent study, Mackle compared the

subjective tracheoesophageal pressure symptoms associated with

substernal goitres with objective cross-sectional radiographic measurements and found tracheal deviation on radiographic imaging

did not appear to affect airway symptoms (

8). We speculate this is

probably due to the cystic and parenchymatous nature of the benign goiter that allowed the bronchoscope squeezing into the distal

trachea. It may also explain the present patient’s symptom doesn’t

appear as severe as that we can see on the radiological images.

Mediastinal mass may be benign or malignant tumors or cysts

or aneurysms and may arise from the lung, pleura or any of the

components of the anterior mediastinum. The anesthetic considerations for patients with an anterior mediastinal mass will vary according to the individual anatomy, pathology and the proposed surgical procedure (

2). Thus, although there are general principles of

safe anesthesia for these patients, there is the need to individualize

management on a case-by-case basis. As mentioned above,

fiberoptic bronchoscope guided tracheal intubation appears to be

possible and feasible in such patients. Some author proficient in

bronchoscopy even raised a suspicion of why use an ox-cleaver to

“kill a chicken”.CPB might not have been requisite in this patient.

An alternative method of securing the airway is the use of emergency attempts at tracheostomy in the event of total airway obstruction occurring during waiting for operation or induction of

anesthesia (

9). This method was ever considered in the present case

on emergency admission because of unprepared systemic checkup.

However, prophylactic tracheostomy still present a likewise challenge for establishment of the tracheal patency because operation

under local anesthesia may cause the process to be time-consuming

and dangerous due to deviation of normal tracheal anatomy and

tube failing to pass beyond the narrowest part (combination of too

short tube and tracheal stricture may contribute to the situation).

Tracheostomy itself poses a risk as high as excision of the tumor. A

same catastrophic situation may arise during induction of anesthesia and at that time relaxation of airway smooth muscle by anesthetic agents makes the airways more compressible followed by inability to ventilate patients with mediastinal tumors. Tracheostomy

in a hurry is extremely hazardous and even fatal.

Fortunately, we succeeded in alleviating the tracheal obstruction

without any anesthetic complication in this patient. But what if

CPB is not required at all? Medical staffs are fully prepared to deal

with a respiratory and hemodynamic catastrophe, fully communicate with the patient and his/her relatives and finally reach a consensus on treatment strategy and risks. That is perhaps an optimal

choice at present. We believe that CPB via femoral vessels before

induction of anesthesia in such patients is justified while bronchoscope guided tracheal intubation to establish the tracheal patency is

a safe and feasible alternative.