A retrospective cohort study of sintilimab and pembrolizumab as first-line treatments for advanced non-small cell lung cancer

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide (1). Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), as the most common histological type, accounts for more than 85% of all lung cancers, with a predicted 5-year survival of 16% (2). Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as programmed death-1 (PD-1) and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors, have led to a breakthrough in the treatment of advanced NSCLC and prolonged the survival of patients (3-7). Based on the KEYNOTE-024 and KEYNOTE-042 clinical trials, pembrolizumab monotherapy has been approved by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as standard treatment for previously untreated advanced NSCLC with PD-L1 selective expression (8,9). The KEYNOTE-189 and KEYNOTE-407 clinical trials also demonstrated that pembrolizumab in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy can be used as standard therapy for the first-line treatment of advanced NSCLC regardless of PD-L1 expression (10,11).

Sintilimab is a fully human IgG4 monoclonal antibody generated using yeast display technology, which blocks the binding of PD-1 to PD-L1 and PD-L2 (12). Compared with pembrolizumab, sintilimab has a higher binding affinity and unique PD-1 epitopes, which is responsible for its superior anti-tumor activity (13). Based on the ORIENT-11 trial, sintilimab plus chemotherapy with pemetrexed and platinum has been approved by the China National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) for previously untreated, locally advanced, or metastatic non-squamous NSCLC patients without sensitive epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) mutation (14). The China NMPA has also approved sintilimab plus gemcitabine and platinum as first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic squamous NSCLC according to the ORIENT-12 trial (15).

Pembrolizumab and sintilimab have both demonstrated great efficacy and tolerable toxicities in the treatment of advanced NSCLC in clinical trials. These two drugs have several differences in molecular structure and biological characteristics (13). The clinical trials of pembrolizumab were mainly non-Asian population while the trials of sintilimab were mainly Chinese population. A phase II interventional randomized controlled trial (NCT04252365) led by Chinese scholar Wu Yilong was designed to compare sintilimab and pembrolizumab as first-line setting of advanced NSCLC. Patient recruitment is ongoing. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective cohort study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sintilimab and pembrolizumab as first-line treatments in patients with advanced NSCLC, in order to provide guidance for the selection of treatment strategies. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-225/rc).

Methods

Patient characteristics

This retrospective study enrolled consecutive patients with advanced NSCLC who received sintilimab or pembrolizumab, with or without chemotherapy, as the first-line treatment at the First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University and Dushu Lake Hospital Affiliated to Soochow University between November 2018 and October 2021. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (I) patients aged 18 years and older; (II) diagnosis of NSCLC was confirmed by histopathology; (III) patients with clinical stage IIIB–IVB NSCLC according to the 8th edition of American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor, node, metastasis (AJCC TNM) staging system; (IV) patients who received at least 2 cycles of sintilimab or pembrolizumab therapy and completed at least 1 follow-up visit; and (V) non-squamous NSCLC patients confirmed to have no EGFR sensitizing mutation or ALK translocation. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) patients with NSCLC combined with other malignant neoplasms; (II) patients who switched to another PD-1 inhibitor during treatment; and (III) patients whose clinical data was incomplete. The patients were divided into the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group according to the drugs they received during treatment. Patients were followed up through clinic or telephone interview every month and the last follow-up date was November 30, 2021.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (No. 2020199) and Dushu Lake Hospital Affiliated to Soochow University was informed and agreed with the study. It was registered on the China Clinical Trials (ChiCTR2000038584). Individual consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Treatment regimen

Patients received sintilimab or pembrolizumab (200 mg) intravenously every 3 weeks. The chemotherapy agents for patients with non-squamous NSCLC included pemetrexed with or without platinum. The chemotherapy agents for patients with squamous NSCLC included docetaxel, paclitaxel, nab-paclitaxel, or gemcitabine with or without platinum. Chemotherapy agents were administered as follows: pemetrexed 500 mg/m2, intravenously; docetaxel 75 mg/m2, intravenously; paclitaxel 175 mg/m2, intravenously; nab-paclitaxel 100 mg/m2, intravenously; and gemcitabine 1,250 mg/m2, intravenously.

Assessments

The basic clinical data of the patients were collected, including age, gender, smoking status, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG-PS), tumor TNM stage, pathological type, site of distant metastasis, and PD-L1 expression. The results of white blood cell count, neutrophil count, hemoglobin, platelet count, alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, thyroid stimulating hormone, free triiodothyronine, and free thyroxine during therapy were also collected. Chest and abdomen computed tomography (CT) scans and cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed regularly to evaluate the therapeutic response which was defined according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST, version 1.1). Objective tumor responses include complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), and progressive disease (PD). The efficacy parameters include objective response rate (ORR), disease control rate (DCR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). The ORR was defined as the CR plus PR rates. The DCR was defined the combination of the CR, PR, and SD rates. The PFS was defined as the period from the start of sintilimab or pembrolizumab administration to tumor progression or death. The OS was calculated as the time from the start of sintilimab or pembrolizumab administration to any cause of death. All adverse events (AEs) were evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. The primary objective of this study was to compare ORR and PFS between the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group. The secondary objectives were to compare DCR and analyze AEs of the two groups.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test in the baseline characteristics of patients in the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group. The PFS curves were drawn using the Kaplan-Meier method and statistical differences were calculated using a two-sided log-rank test. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a Cox proportional-hazards regression model. For subgroup analysis, the same method was used to calculate PFS after categorizing the patients by age, gender, smoking status, ECOG-PS, tumor TNM stage, pathological type, PD-L1 expression, and treatment strategy. A two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically different. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 7.0 and SPSS version 23.0.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 124 patients with advanced NSCLC who received sintilimab or pembrolizumab, with or without chemotherapy, as the first-line treatment were enrolled in this study. The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1. There were 68 patients (54.8%) in the sintilimab group and 56 patients (45.2%) in the pembrolizumab group. The baseline characteristics of the patients were comparable between the two groups.

Table 1

| Clinicopathological parameters | Sintilimab (n=68) | Pembrolizumab (n=56) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | 0.37 | ||

| <65 years | 25 (36.8) | 25 (44.6) | |

| ≥65 years | 43 (63.2) | 31 (55.4) | |

| Gender, n (%) | 0.90 | ||

| Male | 60 (88.2) | 49 (87.5) | |

| Female | 8 (11.8) | 7 (12.5) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | 0.33 | ||

| Never | 21 (30.9) | 22 (39.3) | |

| Current or past | 47 (69.1) | 34 (60.7) | |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | 0.77 | ||

| 0–1 | 61 (89.7) | 51 (91.1) | |

| ≥2 | 7 (10.3) | 5 (8.9) | |

| TNM stage, n (%) | 0.89 | ||

| III | 19 (27.9) | 15 (26.8) | |

| IV | 49 (72.1) | 41 (73.2) | |

| Pathological type, n (%) | 0.96 | ||

| Non-squamous NSCLC | 41 (60.3) | 34 (60.7) | |

| Squamous NSCLC | 27 (39.7) | 22 (39.3) | |

| Metastasis, n (%) | |||

| Brain | 7 (10.3) | 11 (19.6) | 0.56 |

| Bone | 12 (17.6) | 20 (35.7) | 0.31 |

| Liver | 5 (7.4) | 7 (12.5) | 0.80 |

| Adrenal gland | 4 (5.9) | 6 (10.7) | 0.99 |

| PD-L1 expression, n (%) | 0.22 | ||

| ≥50% | 20 (29.4) | 25 (44.6) | |

| ≥1% and <50% | 20 (29.4) | 17 (30.4) | |

| <1% | 7 (10.3) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Unknown | 21 (30.9) | 11 (19.6) | |

| Treatment strategy, n (%) | 0.48 | ||

| Monotherapy | 9 (13.2) | 10 (17.9) | |

| Combination therapy | 59 (86.8) | 46 (82.1) |

ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; TMN, tumor, node, metastasis; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1.

The median ages were 67 years (36–87 years) in the sintilimab group and 65 years (34–88 years) in the pembrolizumab group. There was a larger proportion of males than females in both groups. A total of 47 patients in the sintilimab group and 34 patients in the pembrolizumab group were past or current smokers. There were 7 patients in the sintilimab group and 5 patients in the pembrolizumab group with ECOG ≥2. In both treatment groups, there was a higher proportion of patients with stage IV tumors compared to patients with stage III tumors. In the sintilimab group, 41 patients were diagnosed with non-squamous NSCLC and 27 patients were diagnosed with squamous NSCLC. In the pembrolizumab group, 34 patients were diagnosed with non-squamous NSCLC and 22 patients were diagnosed with squamous NSCLC. A total of 92 patients underwent a PD-L1 (22C3) expression assay before treatment. In the sintilimab group, 20 patients had high PD-L1 expression (PD-L1 ≥50%), 20 patients had low PD-L1 expression (1%≤ PD-L1 <50%), and 7 patients had negative PD-L1 expression (PD-L1 <1%). In the pembrolizumab group, 25 patients had high PD-L1 expression, 17 patients had low PD-L1 expression, and 3 patients had negative PD-L1 expression. Brain metastases occurred in 7 patients and 11 patients in the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group, respectively. Liver metastasis was detected in 5 patients in the sintilimab group and 7 patients in the pembrolizumab group. In the sintilimab group, 9 patients received sintilimab monotherapy and 59 patients received sintilimab combined with chemotherapy. In the pembrolizumab group, 10 patients received pembrolizumab monotherapy, while 46 patients received pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy.

Efficacy

In the sintilimab group, 34 (50%) patients achieved PR, 27 (39.7%) patients achieved SD, and 7 (10.3%) patients suffered PD. In the pembrolizumab group, 26 (46.4%) patients experienced PR, 24 (42.9%) patients had SD, and 6 (10.7%) patients had PD. The ORR was 50.0% versus 46.4% (P=0.69) and the DCR was 89.7% versus 89.3% (P=0.94) in the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group, respectively. Subgroup analysis was performed based on pathological type. In patients with non-squamous NSCLC, the ORR was 46.3% and 44.1% (P=0.85), and the DCR was 87.8% and 88.2% (P=1.00) in the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group, respectively. In patients with squamous NSCLC, the ORR was 55.6% and 50.0% (P=0.70), and the DCR was 92.6% and 90.9% (P=1.00) in the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2

| Best overall response | Sintilimab | Pembrolizumab | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | n=68 | n=56 | |

| PR | 34 (50.0%) | 26 (46.4%) | |

| SD | 27 (39.7%) | 24 (42.9%) | |

| PD | 7 (10.3%) | 6 (10.7%) | |

| ORR | 50.0% | 46.4% | 0.69 |

| DCR | 89.7% | 89.3% | 0.94 |

| Non-squamous NSCLC | n=41 | n=34 | |

| ORR | 46.3% | 44.1% | 0.85 |

| DCR | 87.8% | 88.2% | 1.00 |

| Squamous NSCLC | n=27 | n=22 | |

| ORR | 55.6% | 50.0% | 0.70 |

| DCR | 92.6% | 90.9% | 1.00 |

PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; ORR, objective response rate; DCR, disease control rate; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer.

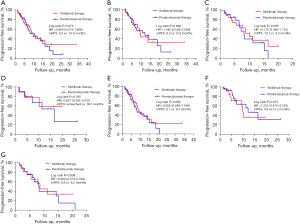

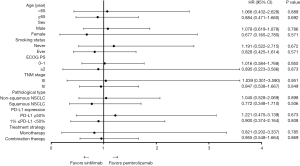

The survival analysis showed that the median PFS was 9.9 months in the sintilimab group and 10.8 months in the pembrolizumab group (HR =0.960; 95% CI: 0.574–1.606; P=0.875). In non-squamous NSCLC, the median PFS was 9.5 and 12.8 months (HR =1.045; 95% CI: 0.528–2.069; P=0.898) in the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group, respectively. In squamous NSCLC, the median PFS was 10.1 months in the sintilimab group compared to 8.2 months in the pembrolizumab group (HR =0.772; 95% CI: 0.348–1.710; P=0.506). Subgroup analysis was performed based on treatment strategy. In the monotherapy group, the median PFS was unreached in the sintilimab group and 16.5 months in the pembrolizumab group (HR =0.821; 95% CI: 0.202–3.337; P=0.785). In the combination therapy group, the median PFS was 9.1 months in the sintilimab group and 8.3 months in the pembrolizumab group (HR =0.955; 95% CI: 0.548–1.664; P=0.869). Subgroup analysis based on PD-L1 expression revealed that patients with high PD-L1 expression had a median PFS of 9.9 months after treatment with sintilimab compared to 12.2 months in patients treated with pembrolizumab (HR =1.221; 95% CI: 0.475–3.139; P=0.673). In patients with low PD-L1 expression, the median PFS was 8.6 months after sintilimab treatment compared to 8.2 months with pembrolizumab treatment (HR =0.900; 95% CI: 0.374–2.164; P=0.808; Figure 1). Subgroup analyses based on age, gender, smoking status, ECOG-PS, and tumor stage showed no significant differences in the PFS between sintilimab and pembrolizumab therapy (Figure 2).

Safety

The incidences of treatment-related AEs of any grades were 91.2% in the sintilimab group and 89.2% in the pembrolizumab group, while the incidences of grade 3–4 AEs were 25.0% and 21.4%, respectively.

The most common AEs in the sintilimab group were anemia (72.1%), nausea (38.2%), decreased white blood cell count (33.8%), decreased appetite (33.8%), and fatigue (30.9%), while in the pembrolizumab group the most common AEs were anemia (58.9%), decreased appetite (37.5%), increased transaminases (37.5%), nausea (33.9%), and vomiting (32.1%). The most common grade 3–4 AEs were decreased neutrophil count (11.8%), anemia (7.4%), decreased white blood cell count (5.9%), and increased transaminases (5.9%) in the sintilimab group, and decreased neutrophil count (7.1%), anemia (7.1%), and decreased white blood cell count (5.4%) in the pembrolizumab group (Table 3). A total of 4 patients in the sintilimab group and 3 patients in the pembrolizumab group discontinued immunotherapy permanently due to grade 3–4 AEs. The other AEs were successfully managed with symptomatic treatment. No patient developed grade 5 AEs.

Table 3

| Adverse event | Sintilimab therapy (n=68) | Pembrolizumab therapy (n=56) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grades 3/4 | All grades | Grades 3/4 | ||

| Any | 62 (91.2) | 17 (25.0) | 50 (89.2) | 12 (21.4) | |

| Anemia | 49 (72.1) | 5 (7.4) | 33 (58.9) | 4 (7.1) | |

| White blood cell count decreased | 23 (33.8) | 4 (5.9) | 14 (25.0) | 3 (5.4) | |

| Neutrophil count decreased | 18 (26.5) | 8 (11.8) | 14 (25.0) | 4 (7.1) | |

| Platelet count decreased | 9 (13.2) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (7.1) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Fatigue | 21 (30.9) | 1 (1.5) | 17 (30.4) | 0 | |

| Nausea | 26 (38.2) | 0 | 19 (33.9) | 0 | |

| Vomiting | 20 (29.4) | 1 (1.5) | 18 (32.1) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Decreased appetite | 23 (33.8) | 0 | 21 (37.5) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Rash | 11 (16.2) | 1 (1.5) | 12 (21.4) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Transaminases increased | 16 (23.5) | 4 (5.9) | 21 (37.5) | 2 (3.6) | |

| Hyperthyroidism | 3 (4.4) | 0 | 4 (7.1) | 0 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 9 (13.2) | 0 | 8 (14.3) | 0 | |

| Pneumonia | 5 (7.4) | 0 | 6 (10.7) | 1 (1.8) | |

Discussion

ICIs that target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway have presented a novel strategy for the treatment of advanced NSCLC, with or without concurrent chemotherapy (6-11,16-20). Nevertheless, patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials (RCTs) must meet numerous restrictive eligibility criteria which may not reflect the more heterogeneous real-world oncological population. As ICIs enter clinical practice, more and more patients who were ineligible for RCTs are now receiving these agents. This includes patients with advanced age, poor ECOG-PS, untreated symptomatic brain metastases, history of autoimmune disease, multiple co-morbidities, and chronic steroid requirements. Recent studies examining the efficacy and AEs associated with immunotherapy for NSCLC in daily practice have observed similar outcomes to those reported in the RCTs (21-23). However, further investigations are warranted to determine whether different ICIs result in different treatment outcomes in NSCLC patients. This current study demonstrated that sintilimab is comparable to pembrolizumab in terms of efficacy and safety as the first-line treatment for advanced NSCLC in the clinical setting. To the best of our knowledge, this report is the first to retrospectively compare the efficacy of two PD-1 inhibitors directly in patients with advanced NSCLC in daily practice.

Pembrolizumab, with or without chemotherapy, has become standard therapy for advanced NSCLC (8-11). The KEYNOTE-189 clinical trial showed that the ORR was 47.6% and the median PFS was 8.8 months in advanced non-squamous NSCLC patients without sensitizing EGFR or ALK genomic aberration who received pembrolizumab plus pemetrexed and platinum-based chemotherapy as the first-line treatment (10). The KEYNOTE-407 clinical trial demonstrated that advanced squamous NSCLC patients who received pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy with carboplatin plus paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel as first-line therapy experienced an ORR of 57.9% and a median PFS of 6.4 months (11). Sintilimab is a PD-1 antibody that was originally co-developed by Innovent Biologics and Eli Lilly and Company. It has been approved for the treatment of classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma in patients who have relapsed or are refractory after ≥2 lines of systematic chemotherapy (24). Sintilimab exhibited specific and high binding affinity to human PD-1, and blocked the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2 (12). Preclinical and clinical studies have showed that sintilimab is a novel, safe, and effective anti-PD-1 antibody in the cancer immunotherapy regimens (13,25). The ORIENT-11 study evaluated the efficacy of sintilimab plus chemotherapy (pemetrexed and cisplatin or carboplatin) in treatment-naive locally advanced or metastatic non-squamous NSCLC patients without EGFR/ALK mutation. They showed that the median PFS was 8.9 months and the ORR was 51.9% (14). The ORIENT-12 study evaluated the effects of sintilimab plus GP as the first-line option for patients with either locally advanced or metastatic squamous NSCLC, and demonstrated that the median PFS was 5.5 months and the ORR was 44.7% (15). Hitherto, a combination of sintilimab and chemotherapy has been widely used in China for the treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC.

The ORR and DCR obtained in our study are consistent with those in clinical trials (10,11,14,15). The ORR reached 44.1% in non-squamous NSCLC and 50% in squamous NSCLC in the pembrolizumab group. In the sintilimab group, the ORR was 46.3% in patients with non-squamous NSCLC and 55.6% in patients with squamous NSCLC. No significant statistical differences in ORR and DCR were observed between the two drugs. However, the median PFS of the two groups in our study was longer than that reported in KEYNOTE-189, KEYNOTE-407, ORIENT-11 and ORIENT-12 clinical trials (10,11,14,15). In the pembrolizumab group, the PFS was 12.8 months in patients with non-squamous NSCLC and 8.2 months in patients with squamous NSCLC. In the sintilimab group, the results were 9.5 and 10.1 months in non-squamous NSCLC and squamous NSCLC, respectively. The following reasons may account for the observed phenomenon. First, the percentage of patients with high PD-L1 and positive PD-L1 expression in our study far exceeded those in clinical trials (10,11,14,15). In patients who received a PD-L1 expression assay before pembrolizumab therapy, 93.3% (42/45) were PD-L1 positive and 55.6% (25/45) had high PD-L1 expression, which exceeded the proportions reported in the KEYNOTE-189 and KEYNOTE-407 clinical trials. In the sintilimab group, the proportion of patients with PD-L1 positive expression and high PD-L1 expression were 85.1% and 42.6%, respectively, which were also higher those reported in the ORIENT-11 and ORIENT-12 studies. Previous studies have indicated that higher PD-L1 expression is associated with prolonged survival of patients with NSCLC (6,9,26). Second, our study consisted of a larger proportion of locally advanced, unresectable, stage III patients. For such patients, durvalumab after concurrent chemoradiotherapy has become the standard therapy. With a median follow-up of 34.2 months, the median PFS was 17.2 months and the median OS was 47.5 months for durvalumab in the phase 3 PACIFIC trial (7). Hence, it is possible that the use of sintilimab and pembrolizumab may also prolong the survival of these patients. Third, the treatment strategies in daily practice are not identical to those in clinical trials. Some patients with advanced squamous NSCLC in the sintilimab group received combination chemotherapy with paclitaxel or nab-paclitaxel, rather than with gemcitabine as used in the ORIENT-12 trial. The different regimens of combination therapy may affect the survival of the patients.

The median PFS was compared between sintilimab and pembrolizumab across various subgroups including age, gender, smoking status, ECOG-PS, tumor TNM stage, pathological type, PD-L1 expression, and treatment strategy. The results demonstrated that the median PFS tended to be longer with administration of sintilimab in patients with advanced age, female, smoking history, ECOG ≥2, stage IV tumor, squamous NSCLC, low PD-L1 expression, monotherapy, and combination therapy. However, none of the differences were statistically significant. These results suggested that, in clinical practice, sintilimab is not inferior to pembrolizumab in terms of PFS in patients with advanced NSCLC. Drug toxicity is an important measure of successful real-world application. AEs were reported in all of the clinicals trials involving immunotherapy (16). The incidence of treatment-related AEs in our study were generally consistent with that reported previously in RCTs (8-11,14,15). The incidence of AEs of any grade, as well as grade 3–4 AEs, was relatively consistent between the sintilimab group and the pembrolizumab group.

There were some limitations to this study. First, this is a retrospective study in two centers, with a relatively small sample size. Hence, information bias is unavoidable and future prospective analysis will be required to further confirm these observations. Second, due to the limited follow-up time, it was not possible to obtain and analyze the OS data. Since OS is the main endpoint in the evaluation of drug efficacy, future studies with a longer follow-up period are warranted. Third, a proportion of patients in this study did not undergo a PD-L1 expression assay before treatment. To date, PD-L1 expression remains the most advanced biomarker for predicting response and prognosis in advanced NSCLC patients (27,28). In addition, treatment selection bias was inevitable in this study. In daily practice, due to various factors, the dose of drugs administered and the chemotherapy regimens cannot be identical to those used in clinical trials.

Conclusions

In summary, the current investigation demonstrated that there was no significant difference in the efficacy between sintilimab and pembrolizumab as the first-line treatment in advanced NSCLC in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This study was funded by the Suzhou Science and Technology Project (No. SLT201917).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-225/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-225/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-225/coif). All authors report this study was funded by the Suzhou Science and Technology Project (No. SLT201917). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Soochow University (No. 2020199), and Dushu Lake Hospital Affiliated to Soochow University was informed and agreed with the study. It was registered on the China Clinical Trials (ChiCTR2000038584). Individual consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin 2021;71:7-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosell R, Karachaliou N. Large-scale screening for somatic mutations in lung cancer. Lancet 2016;387:1354-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbst RS, Garon EB, Kim DW, et al. Five Year Survival Update From KEYNOTE-010: Pembrolizumab Versus Docetaxel for Previously Treated, Programmed Death-Ligand 1-Positive Advanced NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:1718-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borghaei H, Gettinger S, Vokes EE, et al. Five-Year Outcomes From the Randomized, Phase III Trials CheckMate 017 and 057: Nivolumab Versus Docetaxel in Previously Treated Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:723-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Five-Year Outcomes With Pembrolizumab Versus Chemotherapy for Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score ≥ 50. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:2339-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herbst RS, Giaccone G, de Marinis F, et al. Atezolizumab for First-Line Treatment of PD-L1-Selected Patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1328-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Faivre-Finn C, Vicente D, Kurata T, et al. Four-Year Survival With Durvalumab After Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III NSCLC-an Update From the PACIFIC Trial. J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:860-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Chemotherapy for PD-L1-Positive Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1823-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mok TSK, Wu YL, Kudaba I, et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for previously untreated, PD-L1-expressing, locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (KEYNOTE-042): a randomised, open-label, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019;393:1819-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gandhi L, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Gadgeel S, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy in Metastatic Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2078-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Paz-Ares L, Luft A, Vicente D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus Chemotherapy for Squamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2040-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang S, Zhang M, Wu W, et al. Preclinical characterization of Sintilimab, a fully human anti-PD-1 therapeutic monoclonal antibody for cancer. Antibody Therapeutics 2018;1:65-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Fei K, Jing H, et al. Durable blockade of PD-1 signaling links preclinical efficacy of sintilimab to its clinical benefit. MAbs 2019;11:1443-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang Y, Wang Z, Fang J, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Sintilimab Plus Pemetrexed and Platinum as First-Line Treatment for Locally Advanced or Metastatic Nonsquamous NSCLC: a Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Study (Oncology pRogram by InnovENT anti-PD-1-11). J Thorac Oncol 2020;15:1636-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou C, Wu L, Fan Y, et al. Sintilimab Plus Platinum and Gemcitabine as First-Line Treatment for Advanced or Metastatic Squamous NSCLC: Results From a Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Trial (ORIENT-12). J Thorac Oncol 2021;16:1501-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rossi A. Immunotherapy and NSCLC: The Long and Winding Road. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:2512. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wagner G, Stollenwerk HK, Klerings I, et al. Efficacy and safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a systematic literature review. Oncoimmunology 2020;9:1774314. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brahmer J, Reckamp KL, Baas P, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Squamous-Cell Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:123-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borghaei H, Paz-Ares L, Horn L, et al. Nivolumab versus Docetaxel in Advanced Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1627-39. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reck M, Mok TSK, Nishio M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower150): key subgroup analyses of patients with EGFR mutations or baseline liver metastases in a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:387-401. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pasello G, Pavan A, Attili I, et al. Real world data in the era of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs): Increasing evidence and future applications in lung cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2020;87:102031. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mencoboni M, Ceppi M, Bruzzone M, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Patients with Advanced Non Small-Cell Lung Cancer in Real-World: Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:1388. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Knetki-Wróblewska M, Kowalski DM, Krzakowski M. Nivolumab for Previously Treated Patients with Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer-Daily Practice versus Clinical Trials. J Clin Med 2020;9:2273. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hoy SM. Sintilimab: First Global Approval. Drugs 2019;79:341-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Yi Y. Recent updates on Sintilimab in solid tumor immunotherapy. Biomark Res 2020;8:69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reck M, Rodríguez-Abreu D, Robinson AG, et al. Updated Analysis of KEYNOTE-024: Pembrolizumab Versus Platinum-Based Chemotherapy for Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer With PD-L1 Tumor Proportion Score of 50% or Greater. J Clin Oncol 2019;37:537-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alex F, Alfredo A. Promising predictors of checkpoint inhibitor response in NSCLC. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2020;20:931-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bellesoeur A, Torossian N, Amigorena S, et al. Advances in theranostic biomarkers for tumor immunotherapy. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2020;56:79-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: J. Teoh)