Multidisciplinary team approach on tracheoesophageal fistula in a patient with home ventilator

Introduction

In adults, pathologic connections between the esophagus and trachea are uncommon. Most tracheoesophageal fistulas (TEFs) in adults are acquired and are due to esophageal or lung cancer (1-3). However, benign conditions, such as prolonged endotracheal intubation or tracheostomy, endoscopic intervention, infectious diseases, trauma, surgery, and caustic ingestion, can cause TEF (4). Recently, we experienced a case with TEF who had been supported by a long-term home ventilator due to ischemic injury caused by tracheostomy tube cuff pressure and met a treatment challenge due to the location and size of the TEF, the size of the trachea, stenosis of the esophagus inlet, performance status, and negative attitude of the patient and his family towards the active treatment. Here, we present this case and the challenges involved in the treatment of TEF with multidisciplinary team approach. We present the following article in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-675/rc).

Case presentation

First admission (from August 2018 to October 2018)

A 68-year-old man was transferred to our hospital due to dyspnea and a femoral neck fracture. Ten years ago, he had received radiation therapy due to tonsil cancer with no evidence of recurrence but suffered from recurrent aspiration. He refused nasogastric (NG) tube or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) feeding. He was admitted to a secondary hospital for nutritional support due to malnutrition. However, he slipped and broke his femur. During this admission, he refused an operation on his femur and felt dyspnea aggravation, and thus was transferred to our tertiary hospital.

Following admission, we diagnosed aspiration pneumonia and recommended nothing per oral. However, 5 days later, his mother gave him vegetable soup with solid materials, which resulted in respiratory failure and shock. He was intubated and transferred to the intensive care unit(ICU) for ventilator care and monitoring.

We performed a bronchoscopy and extracted several vegetables (pieces of carrot, potato). He recovered from his pneumonia but had difficulty in liberating from the ventilator. We recommended tracheostomy, but his family initially refused. Our sustained persuasion with his family over 2 months led to their agreement, and he received percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT) on October 5th, 2018. He was discharged to a nursing hospital with a home ventilator on October 22nd, 2018.

Second visit to the emergency room (ER) (June 15th, 2019)

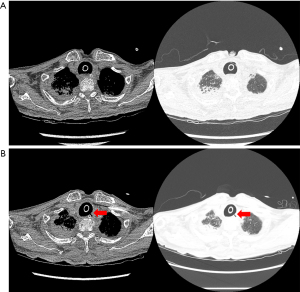

Eight months later, he visited our ER with complaints of fever and dyspnea. We had no available beds in the ICU; thus, he was transferred to another hospital. His chest computed tomography (CT) images showed pneumonia with no evidence of TEF (Figure 1A).

Third admission (July 25th–August 28th, 2019)

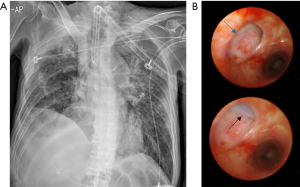

After 1 month, he visited our ER because the secretion from the tracheostomy tube (T-tube) was suspiciously similar to the enteral feeding materials from the nasogastric tube. The chest CT images revealed TEF (Figure 1B) at the upper level. We noticed continuous leakage of the ventilator circuit and changed the T-tube to an endotracheal tube (8.5 mm) as well as inflated the balloon to the maximum to prevent leakage (Figure 2A). Bronchoscopy revealed an oval-shaped, well-margined TEF that was 2 cm in diameter, located on the left side of the proximal trachea, and the NG tube was visible through the TEF (Figure 2B).

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

iMDT discussion 1

Question 1: What is the best optional treatment for his TEF (2 cm sized located in the upper trachea in a patient with malnutrition and a home ventilator)?

Expert opinion 1 (Dr. Hon Chi Suen)

In general, wean off the ventilator, improve the nutrition and treat any infection. Following this, perform tracheal resection and construction (removing the part with the fistula), repair the esophageal defect by two-layer closure (mucosa and muscle) and interpose vascularized healthy tissue between the esophagus and trachea to prevent a recurrence.

Expert opinion 2 (Dr. Jacopo Vannucci)

The best option of treatment is surgery but local and general conditions need to be assessed. Surgery for TEF requires specific skills and knowledge. Specifically, considering the severe condition and long history of medical events, surgery is likely to fail if not supported by dedicated medical support. Malnutrition and the impossibility to wean the patient from the ventilator are both negative prognostic factors and are even worse together. In my opinion the technical details that could not be discussed in such a case are: double-layer esophageal suture, interrupted suture of the airway side of TEF; segmental resection remains the first option; however, suture alone (without segmental airway resection and anastomosis) is never excluded completely before surgery especially in case of very large and old fistulas. Interposed muscle flap is more than important. A fresh tracheostomy below the anastomosis could be helpful (very rare choice) but the possibility to perform a new stoma depends on different parameters: distance between TEF and stoma, condition of the old stoma, length of the remaining trachea, length of the airway to be removed, and airway mobility and infection. A long segmental resection, with primary closure of the esophagus, no anastomosis protection (muscle flap) and impossible weaning from ventilator is an extremely challenging condition for possible success. In this case, the patient refused PEG; I think there is no space for further discussion in planning TEF surgical repair if PEG or other nutritional support are refused.

Expert opinion 3 (Dr. Alfonso Fiorelli)

I believe that the best option for this patient was a best supportive care (5). Endoscopic treatment with standard airway and/or esophageal stents was not available for the characteristics of the fistula and patient’s anatomy, while surgery was contraindicated due to poor patient conditions and the presence of infection of fistula margins that prevented the success of direct suture. In case of improvement of patient’s clinical condition and control of infection, then direct surgical repair may be re-considered.

Treatment and follow up

We consulted a radiologist, gastroenterologist, pulmonary interventionist, and chest surgeon.

Input from the Department of Radiology

The radiologist said that esophageal stent insertion was impossible owing to the high level of TEF in the esophagus.

Input from the Department of Gastroenterology

He did not agree with the placement of an endosponge and endoluminal vacuum therapy due to the large size of the TEF.

Input from the Department of Pulmonary Intervention

He informed us that there was no stent available that could cover the patient’s large trachea.

Input from the Department of Thoracic Surgery

He recommended primary closure operation after improving the malnutrition via PEG insertion and liberation of the home ventilator.

Input from intensivists (Department of Pulmonology)

We thought that his liberation from the ventilator was impossible due to his muscle weakness.

The primary esophagus closure operation required the preceding PEG procedure, but again, his family refused. Finally, we gave up on the primary treatment of TEF after 1month. He was discharged to a nursing hospital, with his family members agreeing to withdraw from further life-sustaining treatment.

iMDT discussion 2

Question 2: Is there another treatment options which is applicable to this patient? Have you any experience of atrial septal defect occluder device to TEF?

Expert opinion 1 (Dr. Hon Chi Suen)

I do not have experience in the use of an atrial septal defect occluder. I do not think it is going to work. The main reason is the occluder will cause pressure necrosis of the edge of the defect and it will actually enlarge the defect with time. Secondly, for a 2-cm fistula, the bigger size occluder will distort the trachea and esophagus.

Expert opinion 2 (Dr. Jacopo Vannucci)

No, I do not have any experience. Despite my total inexperience on this, I do not suggest glues and occluders in such complex cases.

Expert opinion 3 (Dr. Alfonso Fiorelli)

I do not have any experience with an atrial septal defect occluder device for management of TEF, however, there are two other options, not reviewed for this case. (I) The trans-tracheotomy closure of the fistula under endoscopic view, as previously reported by our group (6). Under general anesthesia, the patient is intubated using a rigid bronchoscopy. The cannula was removed and a standard needle-holder is inserted through the tracheotomy. The tear is closed from the distal to the proximal ends with interrupted stitches. Following this, a Montgomery T tube is inserted to protect the suture and maintain the air-way patency. (II) The use of a 3D model (7,8) could assist in producing a customized stent that fits the airway anatomy of this patient better than standard stents.

Last admission (October 4th–October 25th, 2019)

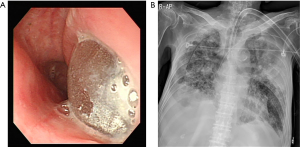

The patient and his family changed their minds and wanted to receive the PEG procedure in our hospital. He was admitted into our ICU, and we planned esophagogastroscopy and PEG. However, the routine scope could not enter his esophagus owing to the esophagus inlet stenosis. It was a complication caused by the radiation therapy used to treat his tonsil cancer. Thus, the PEG procedure was impossible. A thinner scope could investigate the esophagus, and we could see the balloon of the endotracheal tube in the esophagus (Figure 3A). We discussed with the surgeon regarding jejunostomy, but the situation did not appear hopeful considering the patient’s general condition, including malnutrition. During this time, pneumonia (Figure 3B) and septic shock occurred, and the patient died 3 weeks after admission.

iMDT discussion 3

Question 3: In general, surgeons want to prepare the nutritional condition and control infection of the patient before the primary surgery of TEF; however it is very difficult to achieve these in the field. Most adult patients with TEF have comorbidities and they usually show their deconditioning at the diagnosis. In addition, the delay of primary operation could miss the chance of cure. What is the best timing for operation?

Expert opinion 1 (Dr. Hon Chi Suen)

The best timing is when the above “ideal” situation is achieved. Indeed, the “ideal” situation may not be achievable and one has to judge and operate when the best “ideal” time has been reached.

Expert opinion 2 (Dr. Jacopo Vannucci)

In case of sufficiently restored general conditions, the earlier the operation may be performed the better it is. Good tissues heal better. At the same time, surgeons should contextualize the operation because surgery for TEF is a single chance. When patients have pneumonia, sepsis, malnutrition and are dependent on the ventilator, surgery must be suspended and priority is given to general clinical improvement with multidisciplinary support. In most cases this is the key for a successful treatment.

Expert opinion 3 (Dr. Alfonso Fiorelli)

Poor clinical conditions and the presence of infection prevent the healing of the fistula after surgery (9). Thus, surgery should be delayed until the infection is successfully controlled and an improvement in the patient’s clinical condition is obtained.

Discussion

In this case, TEF occurred for 1 month in another hospital after 8 months of tracheostomy, and we assessed that high cuff pressure of the T-tube caused ischemic injury in the trachea. We sought to find the best treatment option for him with a multidisciplinary team, but the conservative or interventional treatments were not suitable for him due to the size and location of the TEF and the size of the trachea. Moreover, the patient and his family refused invasive procedure at first, especially PEG insertion, which delayed the preparation for surgical repair. He showed progressive malnutrition and died due to pneumonia with septic shock.

In a previous report, the principal complications for nonmalignant TEFs are tracheo-bronchial contamination and poor nutrition. Without prompt palliation, death occurs rapidly with a mean survival time between 1 and 6 weeks in patients who are treated with supportive care alone (4). Currently, there are various treatment options for TEF (conservative, interventional, or surgical repair). Interventional modalities of treatment also had been attempted including hybrid insertion of a T-tube, endoscopic esophageal stenting, endoscopic clipping of the fistulous tract, using an atrial septal defect occluder device, and endosponge placement with endoluminal vacuum therapy, and so on (3,10,11). However, these interventions are not always applicable due to the character of the TEF or each hospital’s capacity.

There are various surgical repair options for TEF. However, the operation requires good nutrition status of the patient, liberation of the ventilator, and has the infection under control (12-14). In fact, after the diagnosis of TEF, clinicians always try to stabilize the patient but these preconditions are not easy to meet.

In conclusion, the devastating TEF in this patient with a ventilator demonstrates the importance of early decision-making in the treatment modality and process, with the compliance of the patient, using a multidisciplinary team for early intervention before the patient’s deconditioning.

And also, we believe this case will advocate the importance of monitoring the cuff pressure and present the practical challenges of treating TEF in patients with long-term ventilators.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-675/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-675/coif). HCS serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Chen YH, Li SH, Chiu YC, et al. Comparative study of esophageal stent and feeding gastrostomy/jejunostomy for tracheoesophageal fistula caused by esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One 2012;7:e42766. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balazs A, Kupcsulik PK, Galambos Z. Esophagorespiratory fistulas of tumorous origin. Non-operative management of 264 cases in a 20-year period. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;34:1103-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sersar SI, Maghrabi LA. Respiratory-digestive tract fistula: two-center retrospective observational study. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2018;26:218-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reed MF, Mathisen DJ. Tracheoesophageal fistula. Chest Surg Clin N Am 2003;13:271-89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fiorelli A, Esposito G, Pedicelli I, et al. Large tracheobronchial fistula due to esophageal stent migration: Let it be! Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2015;23:1106-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caronia FP, Reginelli A, Santini M, et al. Trans-tracheostomy repair of tracheo-esophageal fistula under endoscopic view in a 75-year-old woman. J Thorac Dis 2017;9:E176-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fiorelli A, Ferrara V, Bove M, et al. Tailored airway stent: the new frontiers of the endoscopic treatment of broncho-pleural fistula. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:S1339-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andreetti C, Poggi C, Rendina EA, et al. Temporary Treatment of Complex Subglottic Stenosis by an On-Site Customized Stent. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;31:319-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caronia FP, Fiorelli A, Santini M, et al. A new technique to repair huge tracheo-gastric fistula following esophagectomy. Ann Transl Med 2016;4:403. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ersoz H, Nazli C. A new method of tracheoesophageal fistula treatment: Using an atrial septal defect occluder device for closure-The first Turkish experience. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;66:679-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee HJ, Lee H. Endoscopic vacuum-assisted closure with sponge for esophagotracheal fistula after esophagectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2015;25:e76-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah CP, Yeolekar ME, Pardiwala FK. Acquired tracheo-oesophageal fistula. J Postgrad Med 1994;40:83-4. [PubMed]

- Akaraviputh T, Angkurawaranon C, Phanchaipetch T, et al. Platysma myocutaneous flap interposition in surgical management of large acquired post-traumatic tracheoesophageal fistula: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014;5:282-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vinnamala S, Murthy B, Parmar J, et al. Rendezvous technique using bronchoscopy and gastroscopy to close a tracheoesophageal fistula by placement of an over-the-scope clip. Endoscopy 2014;46 Suppl 1 UCTN:E301.