Development and linguistic validation of the Korean version of the Severe Asthma Questionnaire

Highlight box

Key findings

• We developed the Korean version of the Severe Asthma Questionnaire (SAQ-K) through linguistic validation process.

What is known and what is new?

• Severe asthma affects various aspects of life. The SAQ is a self-administered questionnaire originally developed in the UK to address health issues specific to severe asthma.

• The content of the SAQ was relevant to Korean patients. Cognitive debriefing verified that the Korean version of the SAQ items were well understood and did not require further modification.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The SAQ-K can be used as an assessment tool in further clinical studies of severe asthmatic patients in Korea.

Introduction

Severe asthma presents in about 5% of adult asthmatics but is responsible for a large proportion of health care resources and socioeconomic burden associated with asthma (1-3). Severe asthma also has a large impact on the quality of life (QOL) of the affected patients and their families (4). QOL is considered a key component of the patient burden and also is an important variable in evaluating and choosing the appropriate therapeutic interventions (5,6). However, disease-specific QOL is not well captured by conventional or generic tools (7-9). Hence, disease-specific QOL instruments should be utilized to ensure that they accurately measure the status of severe asthmatics. There are several QOL instruments that have been used in prior studies of asthma, but the content is not specific to the health issues of severe asthma, such as the complications of oral corticosteroid (OCS) treatments (7,8,10).

The Severe Asthma Questionnaire (SAQ) is a self-administered questionnaire, designed to measure the health issues specific to severe asthma patients. It was originally developed and validated in English by Hyland et al. in 2018 in response to the lack of specificity of the former QOL assessment tools (7,11-13). The SAQ has since been validated for use and translated into various language versions (13,14), and is becoming widely used in registry studies of patients with severe asthma (15). The present study aimed to develop a Korean language version of the SAQ (SAQ-K), based on the original English version, with the translation and linguistic validation. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1415/rc).

Methods

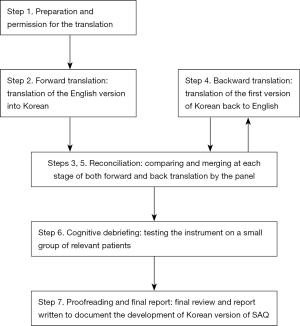

The English version of the SAQ questionnaire was translated into Korean and further adapted to Korean cultural and social differences. This work was carried out by a panel of 7 Korean asthma specialists who performed a linguistic validation process and 15 severe asthma patients who reported potential linguistic and understanding difficulties of the instrument. The enrolled patients were ≥19 years of age and diagnosed with severe asthma in accordance with American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) guidelines (16). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. GDIRB2020-073) and written informed consent for participation was obtained from all study patients. Figure 1 depicts an overview of the process.

The SAQ

The original SAQ is a 16-item questionnaire related to the disease burden experienced over the last two weeks. Patients provide responses to each item, which are assigned a score from 1 to 7 points, and the average produces the SAQ score. Based on the requests of patients, the SAQ also includes the SAQ-global score, which is a value given on a 100-point scale that assesses the QOL during the two weeks prior to taking the questionnaire, and also in the worst and best months of the year (13). Numerically higher scores of the SAQ score indicate better QOL status, and the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) for the SAQ score is 0.5 and for the SAQ-global score is 11 (12). Before our study began, the corresponding author contacted the original developers of the SAQ to gain permission to develop the Korean version.

Forward translation

The original English version of the SAQ was translated into Korean by two bilingual translators, who were also asthma specialists. Each translator was a native Korean speaker but had lived in the United States for several years and was fluent in English. They were both informed of the guidelines for this forward translation (17) and worked independently with no contact allowed between them during this process.

Reconciliation

The two bilingual translators reviewed and compared the two translations and produced a reconciled Korean version under the supervision of the corresponding author.

Backward translation

Then the reconciled Korean version was back-translated by two native English speakers who were also fluent in Korean. These new translators were instructed to execute a literal translation. After the translator completed the task, the original SAQ and the backward translations were reviewed for conceptual equivalence. Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved by the panel of asthma specialists. The panel then convened to produce and carefully proofread the Korean version of the SAQ in accordance with the original questionnaire structure.

Cognitive debriefing

The Korean version of the SAQ was provided to a group of severe asthma patients to determine the content acceptability and to assess their linguistic understanding of each item. On completion of the questionnaire, each participant completed a one-on-one cognitive debriefing session. They provided feedback on any difficulties in reading or understanding the questionnaire items without help, or whether there was any ambiguous terminology. In each case, an experienced research nurse gathered their feedback and presented it to the panel.

Finalization

The panel reviewed the patient feedbacks presented during the debriefing and discussed whether further corrections were needed to the translated SAQ. After the final evaluations of the translation and checking for errors in spelling or format, the SAQ-K was finalized.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were utilized to present the baseline characteristics of 15 patients who participated in the cognitive debriefing process. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Translation and linguistic validation process

Overall, the questionnaire content was considered relevant by the panel of clinicians. However, we found several items that warranted some modification to keep conceptual equivalence during the forward translation process into Korean (Table 1). For example, the item 4, “My jobs around the house” was translated into “family life and domestic affairs”. In item 5, “Can’t do all I want to do” was translated into “going on achievement and failure to do what you want for work or study”; and “Leave blank if not in work or education” was translated into “leave blank if you don’t have any work life or training activities and leave blank if you are not an office worker or a student”. In item 8, “fed up, blue” was translated into “tiredness, melancholy mood and listlessness, disappointment”. In item 9, “Snap at people, get angrier than I should” was translated into “get angry at another person, get angrier than I should and snap at people, get angrier than usual”. In item 14, “Problems at night” was translated into “sleep disorder and sleep problems”.

Table 1

| English version | Forward Korean translation version | Final reconciled Korean version | Comments of the study participants | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAQ | ||||

| 1. My social life. For example: visiting friends, walking with friends, talking with friends, going to bars/restaurants, and parties | 1. 사회 생활. 예: 친구 방문, 친구와 걷기, 친구와 대화하기, 바/식당/파티 방문. | 1. 사회 생활. 예: 친구 방문, 친구와 걷기, 친구와 대화하기, 바/식당/파티 가는 것. | ||

| 2. My personal life. For example: washing, dressing, looking after myself, love life | 2. 개인 생활. 예: 씻기, 옷 입기, 스스로 돌보기, 성 생활. | 2. 개인 생활. 예: 샤워, 목욕, 옷 입기, 스스로 돌보기, 성 생활. | Participants wanted a clearer meaning of washing | This was rephrased to provide a more detailed explanation |

| 3. My leisure activities. For example: walking for pleasure, sports, exercise, travelling, taking vacations | 3. 여가 생활. 예: 산책하기, 운동, 스포츠, 여행, 휴가 보내기. | 3. 여가 생활. 예: 산책하기, 스포츠, 운동하기, 여행하기, 휴가 가기. | ||

| 4. My jobs around the house. For example: housework, shopping, home maintenance, gardening | 4. 가정 생활. 예: 집안일, 쇼핑, 집안 유지보수, 정원 손질. | 4. 가사 업무. 예: 집안일, 장 보기, 집안 유지보수, 정원 가꾸기. | ||

| 5. My work or education. For example, missing days, can’t do all I want to do | 5. 직장 및 교육 활동. 예: 결근 혹은 결석, 성취도. | 5. 직장 또는 학교 생활. 예: 결근 또는 결석, 원하는 일이나 공부를 하지 못함. | ||

| Leave blank if not in work or education | 직장 생활이나 교육활동이 없으면 빈칸으로 비워 두십시오. | 직장인 또는 학생이 아니라면 비워 두셔도 됩니다 | ||

| 6. My family life–how it affects me. For example: caring for children, family responsibilities | 6. 가족 생활 –본인에게 미치는 영향력. 예: 자녀 돌봄, 가족 부양 책임. | 6. 가족 생활 – 본인에게 미치는 영향. 예: 아이 돌보기, 가족 부양 의무. | Some participants said that they could not answer the question as they were staying single | Phrases were retained without changes |

| 7. My family life–how it affects others. For example: others taking time off work, problems with childcare, family members becoming upset | 7. 가족생활-가족구성원에 미치는 영향력. 예: 가족구성원의 활동 제한, 자녀 돌봄으로 인한 문제, 가족 구성원의 불편 호소. | 7. 가족 생활 –가족 구성원에게 미치는 영향. 예: 가족 중 누군가가 본인으로 인해 휴가를 내야 하거나, 아이를 돌보는데 문제가 생기거나, 가족 중 누군가가 화를 냄. | Some participants said that they could not answer the question as they were staying single | Phrases were retained without changes |

| 8. Depression. For example, feeling sad, fed up, blue | 8.우울함. 예: 슬픈 느낌, 무기력함, 기분 저하. | 8. 우울. 예: 슬프거나, 싫증나거나, 울적해지는 것. | ||

| 9. Irritable. For example, snap at people, get angrier than I should | 9. 민감함. 예: 상대방에게 날카로운 말투로 말함, 평소보다 화가 많음. | 9. 예민함. 예: 상대방에게 버럭 화를 내거나, 필요 이상으로 화를 내는 것. | ||

| 10. Anxiety in general. For example, worry about things, always on edge | 10. 일반적인 불안감. 예: 일상에 대한 걱정, 가장자리에 선 듯한 아슬아슬한 느낌. | 10. 전반적인 불안. 예: 일상에 대한 걱정, 항상 불안하거나 초조해지는 것. | ||

| 11. Worry that asthma may get worse. For example, medicines no longer help, more frequent attacks | 11. 천식 악화에 대한 걱정. 예: 치료효과 없음, 자주 악화되는 상황. | 11. 천식 악화에 대한 걱정. 예: 약이 더 이상 듣지 않거나, 더 자주 악화되는 것. | ||

| 12. Worry about long term side effects of medicines. For example, worry about cataracts, diabetes, bone fracture | 12. 약제 사용에 따른 부작용 걱정. 예: 백내장, 당뇨, 골절에 대한 걱정. | 12. 약제 장기 복용 부작용에 대한 걱정. 예: 백내장, 당뇨, 골절에 대한 걱정. | ||

| 13. Getting tired. For example, feeling tired for no reason, waking in the morning feeling tired | 13. 피곤함. 예: 이유 없이 피곤함, 아침 기상 시 개운한 느낌이 없음. | 13. 피로감. 예: 이유 없이 피곤하거나, 아침에 일어나면 피로를 느끼는 것. | ||

| 14. Problems at night. For example, difficulty going to sleep, being woken very easily, waking often at night | 14. 야간 수면장애. 예: 잠들기 힘듦, 일찍 잠에서 깨어남, 잠은 들지만 자주 깸. | 14. 수면 문제. 예: 잠 들기 어렵고, 쉽게 잠에서 깨거나, 자주 잠에서 깨는 것. | ||

| 15. The way I look. For example, my weight, my skin bruises easily, using medicines in public, other people judging me | 15. 나를 보는 시선. 예: 체중 변화, 쉽게 멍듦, 대중 장소에서 약제 사용, 자신에 대한 타인의 평가. | 15. 내 모습과 이미지. 예: 나의 체중 변화, 쉽게 멍들거나, 사람들 앞에서 약을 먹는 것, 다른 사람들이 나를 안 좋게 평가하는 것. | Some participants did not understand what was meant by “The way I look.” | This was rephrased using simpler language |

| 16. Problems with food. For example, I find I get very hungry, I just can’t stop eating, stomach problems (e.g., pain, bloating, etc.) | 16. 식습관 문제. 예: 매우 허기짐, 참을 수 없는 식탐, 위 증상 (예: 복통, 복부팽만감 등) | 16. 음식과 관련된 문제. 예: 배고픔을 많이 느끼거나, 먹는 것을 멈출 수 없거나, 소화가 안되는 것 (예: 복통, 더부룩함 등). | Some participants had difficulty understanding the example of “stomach problem” | This was rephrased using simpler language |

| SAQ-global scale | ||||

| 1. During the last TWO WEEKS, my quality of life has been ( ) write a number | 1. 최근 2주 동안의 나의 삶의 질은( )점이었다 (숫자로 기입). | 1. 지난 2주 동안의 나의 삶의 질은( )점이었다 (숫자로 기입). | ||

| 2. During the month of the year when my asthma is at its BEST, my quality of life has been ( ) write a number | 2. 지난해 천식이 가장 잘 조절되었던 한달 동안 나의 삶의 질은 ( )점이었다 (숫자로 기입). | 2. 지난 1년간 나의 천식 증상이 가장 좋았던 달 기준으로 나의 삶의 질은 ( )점이었다 (숫자로 기입). | ||

| 3. During the month of the year when my asthma is at its WORST, my quality of life has been ( ) write a number | 3. 지난해 천식이 가장 잘 조절되지 않았던 한달 동안 나의 삶의 질은 ( )점이었다 (숫자로 기입). | 3. 지난 1년간 나의 천식 증상이 가장 나빴던 달 기준으로 나의 삶의 질은 ( )점이었다 (숫자로 기입). |

English version of SAQ is reproduced with the permission from Hyland et al. (13). SAQ-K, a Korean language version of the SAQ; SAQ, severe asthma questionnaire.

The reconciled changes were as follows: taking vacation (item 3), domestic affairs (item 4), what you want to do for work or study, leave blank if you are not an office worker or a student (item 5), family support responsibility (item 6), someone in the family taking time off work, trouble taking care of their child, getting anger (item 7), tiredness, melancholy mood (item 8), get angry at another person, get angrier than I should (item 9), always nervous or anxious (item 10), the medicine doesn’t work anymore (item 11), worry about long term side effects of medicines (item 12), tiredness (item 13), sleep problems (item 14), taking medicine in public, other people judging me (item 15), and diet-related problems (item 16). In the backward translation phase, the translated sentences were determined by the panel, to have good agreements with the original SAQ.

Cognitive debriefing process and finalization

After completion of the final backward translation of the SAQ, 15 patients provided feedback on this questionnaire during the cognitive debriefing process. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 2. Their mean age was 46.1 years and 53.3% of them were male. The baseline percent predicted FEV1, and FEV1/FVC were 62.3% and 63.1%, respectively. The ACT scores at the baseline were 16. Based on their health care coverage (18), a quarter of our subjects were determined to be from a low socioeconomic background. The mean total SAQ and SAQ-global scores during the last two weeks were 4.2 and 58.3, respectively (Table 3). The mean best and worst SAQ-global scores of the year were 68.0 and 27.5, respectively.

Table 2

| Characteristics | Finding |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 46.1±14.4 (range: 22–64) |

| Age group | |

| 20–39 years | 4 (26.7) |

| 40–59 years | 7 (46.6) |

| ≥60 years | 4 (26.7) |

| Male | 8 (53.3) |

| FEV1, % of predicted value | 62.3±17.1 |

| FEV1/FVC, % | 63.1±15.3 |

| ACT | 15.9±4.4 |

| Socioeconomic status† | |

| Low | 4 (26.7) |

| Number of exacerbations in the previous year | 0.87±1.30 |

| Number of serious exacerbation in the previous year‡ | 0.40±0.74 |

| OCS use in the previous year§ | 10 (66.7) |

| Prescribed asthma medications | |

| ICS/LABA | 4 (26.7) |

| ICS/LABA/LAMA | 11 (73.3) |

| LTRA | 13 (86.7) |

| Sustained systemic corticosteroids | 3 (20.0) |

| Biologics | 1 (6.7) |

Values are presented as a number (%) or mean ± standard deviation. †, we stratified the population by socioeconomic status, i.e., into those covered by National Health Insurance and Medical Aid; ‡, emergency room visit and admission for asthma. §, OCS users were defined as those who were prescribed OCS as an asthma treatment in the previous year. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ACT, Asthma Control Test; OCS, oral corticosteroid; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting beta-2 agonists; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonists; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist.

Table 3

| Patients | Total domain score | Global Quality of Life Score (during the last two weeks) | Global Quality of Life Score (best of the year) | Global Quality of Life Score (worst of the year) | Time to conduct survey (minutes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.0 | 70 | 70 | 18 | 10 |

| 2 | 2.8 | 60 | 80 | 0 | 25 |

| 3 | 3.8 | 60 | 60 | 60 | 7 |

| 4 | 5.1 | 60 | 70 | 15 | 2 |

| 5 | 4.8 | 60 | 80 | 20 | 13 |

| 6 | 5.5 | 95 | 90 | 95 | 4 |

| 7 | 2.1 | 20 | 30 | 15 | 3 |

| 8 | 3.1 | 40 | 70 | 15 | 7 |

| 9 | 2.5 | 40 | 70 | 5 | 4 |

| 10 | 3.5 | 60 | 45 | 45 | 5 |

| 11 | 4.3 | 60 | 70 | 5 | 4 |

| 12 | 4.5 | 60 | 80 | 25 | 4 |

| 13 | 3.6 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 4 |

| 14 | 5.1 | 90 | 90 | 15 | 8 |

| 15 | 4.9 | 70 | 85 | 50 | 3 |

| Mean | 4.2 | 58.3 | 68 | 27.5 | 7 |

SAQ, severe asthma questionnaire.

The study participants required an average of 7 minutes to complete the SAQ-K responses. Most of them indicated that the translated questionnaire was well written and that its format of the questionnaire was easy to follow. These subjects gave feedback, however, that some expressions were difficult to understand (Table 1). For example, in item 2 of the SAQ, they indicated that a clearer meaning of the term washing was needed. The panel thus decided to provide a more detailed explanation, such as taking a shower or bath. In items 6 and 7, unmarried single subjects commented that they could not respond to the question. However, since the problem in this case was due to a subjective interpretation, the panel decided not to alter the original translated text. In item 15, some patients commented that they did not really understand what was meant by “The way I look”. This phrasing was thus judged by the panel to require some adjustment to reflect self-image and appearance while maintaining the intended meaning in the original version. In item 16, some patients had difficulty understanding “stomach problem”. The panel therefore modified the Korean translation of this question to clarify the meaning in this case. The reconciled translations were adjusted after cognitive debriefing and proofreading. Then the SAQ-K was finalized (Figure S1).

Discussion

In the present study, we developed the Korean version of the SAQ for use in patients with severe asthma in Korea. The linguistic validation followed the formal steps of forward translation, reconciliation, back translation, reconciliation, and cognitive debriefing, and involved a panel of asthma specialist physicians and severe asthmatics.

In the past, several tools for assessing asthma-related QOL have been developed and used in previous clinical studies (19). Notably, although these tools may be suitable for overall asthmatics, they were not specific to address health issues to severe asthma patients because they fail to capture some of the health-related QOL impacts that reflect the effects of high-intensity treatment such as OCS (10,20). As reported in recent qualitative studies, patients with severe asthma experience physical and psychosocial distress due to asthma exacerbations, live a restricted life with limited physical capability, negative self-perception, or the fear of exacerbations, and suffer from depression and healthy anxiety (7,10,21-23). On the basis of the prior qualitative research findings on severe asthma, the SAQ was intended to measure this disease burden, and the side effects of asthma medication, as perceived by severe asthma patients (7). It was also designed for clinical trial use in severe asthmatic populations where an assessment period of 2 weeks is appropriate for monitoring asthma control.

Cross-cultural adaptation process with an existing questionnaire is a faster, easier and more convenient approach than the development of an entirely new instrument, but cultural and language-specific concerns need to be considered (24). Several methods of cross-cultural adaptation have been introduced previously, and include several stages of confirmation procedures, such as translation, backward translation, reconciliation, and pretesting. In the present study, we produced the SAQ-K through a series of formal steps, which had been previously suggested by the SAQ team (17). In addition, positive feedback on this questionnaire was received from a panel of Korean patients with severe asthma. This study population was assembled with consideration of balancing age, sex, and economic background, as demanded by the SAQ protocol.

This study has two major limitations. Firstly, it focused on linguistic validation but did not analyze the functional utility of SAQ-K, such as reliability and validity. Further research is needed to assess its utility in assessing health status and outcomes in Korean cohorts of severe asthma. Secondly, we performed the cognitive debriefing process with a small number of participants (n=15). It would have been more robust to include a larger number of patients. However, we recruited patients with different demographic and social economic status and clinical severity (including OCS use), and their asthma severity indices were similar to those of previous studies of Korean patients (3).

Conclusions

We described the processes of developing the SAQ-K. Through multiple stages of translation and review in the cross-cultural adaptation process, the semantic and conceptual equivalence of the questionnaire items was maintained. Cognitive debriefing verified that the Korean version of the questionnaire items were well understood and did not require further modification. Through these steps, a Korean version of the SAQ was generated to be used as an assessment tool for health-related QOL in further clinical studies of severe asthma patients in Korea (25).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Prof. Michael Hyland (Plymouth University, Plymouth, UK) and Prof. Matthew Masoli (University of Exeter, Exeter, UK) who developed and validated this tool, for their generosity and for allowing us to translate and adapt the original English version of this questionnaire to Korean.

Funding: This research was supported by a fund (No. 2021ER120100) by Research of Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and by a fund by the Bio & Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (No. 2019M3E5D3073365).

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1415/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1415/dss

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1415/coif). WJS serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease, and declares academic grants from MSD, consulting fees from MSD, GSK, AstraZeneca, and Novartis, and honoraria from MSD, GSK, AstraZeneca, and Novartis. However, these companies are not directly related to this work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB No. GDIRB2020-073) and written informed consent for participation was obtained from all study patients.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Holguin F, Cardet JC, Chung KF, et al. Management of severe asthma: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J 2020;55:1900588. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim BK, Park SY, Ban GY, et al. Evaluation and Management of Difficult-to-Treat and Severe Asthma: An Expert Opinion From the Korean Academy of Asthma, Allergy and Clinical Immunology, the Working Group on Severe Asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2020;12:910-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim MH, Kim SH, Park SY, et al. Characteristics of Adult Severe Refractory Asthma in Korea Analyzed From the Severe Asthma Registry. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019;11:43-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song WJ, Lee JH, Kang Y, et al. Future Risks in Patients With Severe Asthma. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019;11:763-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hossny E, Caraballo L, Casale T, et al. Severe asthma and quality of life. World Allergy Organ J 2017;10:28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Juniper EF, Wisniewski ME, Cox FM, et al. Relationship between quality of life and clinical status in asthma: a factor analysis. Eur Respir J 2004;23:287-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hyland ME, Whalley B, Jones RC, et al. A qualitative study of the impact of severe asthma and its treatment showing that treatment burden is neglected in existing asthma assessment scales. Qual Life Res 2015;24:631-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hyland ME, Lanario JW, Pooler J, et al. How patient participation was used to develop a questionnaire that is fit for purpose for assessing quality of life in severe asthma. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16:24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szentes BL, Schultz K, Nowak D, et al. How does the EQ-5D-5L perform in asthma patients compared with an asthma-specific quality of life questionnaire? BMC Pulm Med 2020;20:168. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song WJ, Won HK, Lee SY, et al. Patients' experiences of asthma exacerbation and management: a qualitative study of severe asthma. ERJ Open Res 2021;7:00528-2020. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Apfelbacher CJ, Jones CJ, Frew A, et al. Validity of three asthma-specific quality of life questionnaires: the patients' perspective. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011793. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Masoli M, Lanario JW, Hyland ME, et al. The Severe Asthma Questionnaire: sensitivity to change and minimal clinically important difference. Eur Respir J 2021;57:2100300. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hyland ME, Jones RC, Lanario JW, et al. The construction and validation of the Severe Asthma Questionnaire. Eur Respir J 2018;52:1800618. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Clérigo V, Cardoso B, Fernandes LS, et al. Severe Asthma Questionnaire: translation to Portuguese and cross-cultural adaptation for its use in Portugal. Rev Port Imunoalergologia 2019;27:233-42. [Crossref]

- Park SY, Kang SY, Song WJ, et al. Evolving Concept of Severe Asthma: Transition From Diagnosis to Treatable Traits. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2022;14:447-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014;43:343-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Severe Asthma Questionnaire [cited 2021 Aug 13]. Available online: http://www.saq.org.uk/download.aspx.

- Bahk J, Kang HY, Khang YH. Trends in life expectancy among medical aid beneficiaries and National Health Insurance beneficiaries in Korea between 2004 and 2017. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1137. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Apfelbacher CJ, Hankins M, Stenner P, et al. Measuring asthma-specific quality of life: structured review. Allergy 2011;66:439-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDonald VM, Hiles SA, Jones KA, et al. Health-related quality of life burden in severe asthma. Med J Aust 2018;209:S28-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Foster JM, McDonald VM, Guo M, et al. "I have lost in every facet of my life": the hidden burden of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1700765. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eassey D, Reddel HK, Ryan K, et al. The impact of severe asthma on patients' autonomy: A qualitative study. Health Expect 2019;22:528-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Apps LD, Chantrell S, Majd S, et al. Patient Perceptions of Living with Severe Asthma: Challenges to Effective Management. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:2613-21.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McKown S, Acquadro C, Anfray C, et al. Good practices for the translation, cultural adaptation, and linguistic validation of clinician-reported outcome, observer-reported outcome, and performance outcome measures. J Patient Rep Outcomes 2020;4:89. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SH, Lee H, Park SY, et al. The Korean Severe Asthma Registry (KoSAR): real world research in severe asthma. Korean J Intern Med 2022;37:249-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]