Pericardial synovial sarcoma presenting with large recurrent pericardial effusion

Introduction

Primary pericardial synovial sarcoma is an extremely rare disorder (1). Because of its clinical rarity and wide histopathological diversity, its diagnosis may potentially be confused with various other pericardial diseases that show a pericardial mass with effusion on echocardiography and chest CT. Its most frequent presenting symptom is signs of cardiac tamponade; subsequent diagnostic imaging, including echocardiography or chest CT, reveals a pericardial mass requiring biopsy for diagnosis (2). Cytogenetic analysis is highly sensitive in the diagnosis and typically shows reciprocal chromosomal translocation (X;18 p11.2;q11.2) (3). However, primary pericardial synovial sarcoma may have only systemic clinical manifestations, including fever, chill, and night sweats, with a large pericardial effusion but without a pericardial mass, and thus may represent a diagnostic challenge. We report the case of a 34-year-old patient with fever and recurrent pericardial effusion for 2 years, who was ultimately diagnosed with primary pericardial synovial sarcoma.

Case presentation

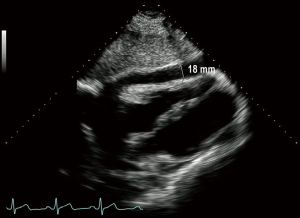

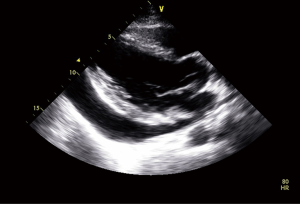

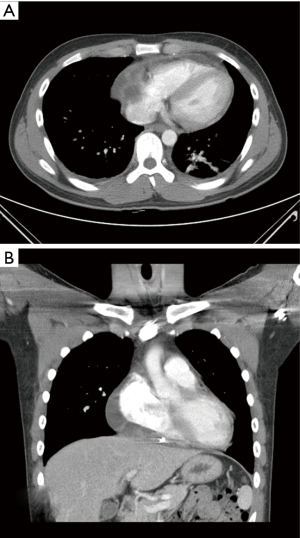

A 34-year-old male visited our hospital because of fever, chill, and malaise that had started 3 days before. The physical examination had no abnormal findings. After admission, the chest X-ray indicated cardiomegaly but the ECG showed normal sinus rhythm. Echocardiography showed a large pericardial effusion and 1,070 mL pericardial fluid of serosanguinous color was drained (Figure 1). Follow-up echocardiography 5 days later showed no pericardial effusion and no sign of any mass. However, the patient still complained of fever, cough, and malaise, while blood tests found a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 0.9 mg/L and a white blood cell count of 4,570/µL. Culture analysis of the pericardial fluid showed no bacteria or neoplastic cells. For further evaluation, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis was performed for respiratory viruses, including adenovirus, respiratory syncytial virus A/B, influenza A/B virus, parainfluenza virus 1/2/3, rhinovirus A/B, metapneumovirus, and coronavirus, but was only positive for influenza A virus. The patient was diagnosed with a respiratory viral infection and pericardial effusion. He was discharged without symptoms after 5 days antiviral therapy with a regular follow-up schedule, but he was not regularly followed up. During follow-up visits, echocardiography showed an initial mild amount of pericardial effusion (right side 18 mm, left side 3 mm at 2 weeks) that progressively increased to a moderate amount 3 months later, though without any clinical symptoms (Figure 2). Admission for evaluation was recommended, but the patient refused because of the lack of symptoms. However, 5 months after discharge he developed facial edema and dyspnea on exertion and he was readmitted for treatment and evaluation. Echocardiography showed a large pericardial effusion (right side 54 mm), while the chest CT, as well as confirming the effusion, revealed a pericardial cystic mass with pericardial thickening (Figure 3). Pericardiocentesis was performed and 1,150 mL of pericardial fluid was drained. However, analysis of the fluid showed no bacteria or malignant cells, while PCR for respiratory viruses and blood cultures also revealed nothing. After the symptoms had been relieved by pericardiocentesis during admission, the patient was recommended to undergo a surgical biopsy to confirm the diagnosis, but he insisted on discharge without further evaluation.

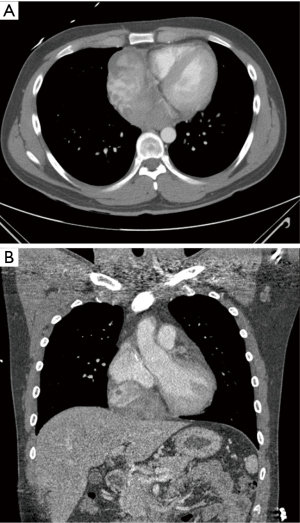

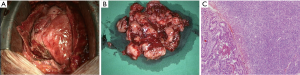

Seven months after the second admission, the patient was readmitted because of dyspnea on exertion with chest pain that had developed 2 days before. Echocardiography showed a 7.7×5.5 cm2 pericardial mass adjacent to the right atrium, with a small amount of pericardial effusion. Cardiac CT revealed a 6.3×10.1 cm2 ovoid pericardial mass compressing the right atrium (Figure 4). Surgical excision was performed, after which microscopic and immunohistochemically analyses were positive for bcl-2 and CD99, while cytogenetic analysis confirmed reciprocal chromosomal translocation (X;18 p11.2;q11.2) (Figure 5). The patient was then diagnosed with primary pericardial synovial sarcoma.

Discussion

We have described the case of a patient with a pericardial synovial sarcoma that had an unusual clinical presentation. Primary pericardial tumor is an extremely rare disorder (1-3). Pericardial cysts and pericardial lipomas are the most common benign pericardial tumors, while mesothelioma is the most common primary malignant tumor of the pericardium. Other primary malignant pericardial neoplasms include a wide variety of sarcomas and lymphomas (4). Primary pericardial sarcoma has a large range of histologic subtypes: angiosarcoma, undifferentiated sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, liposarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and synovial sarcoma (5). Among these, pericardial synovial sarcoma is extremely rare; only 20 cases of synovial sarcoma of the pericardium have been reported in the English language literature (2,3). Histologically, synovial sarcoma has three subtypes: biphasic, monophasic, and poorly differentiated types. The biphasic type, the most frequent, consists of two components: epithelial and spindle cells. The monophasic type has only a spindle cell component and the poorly differentiated type has small round cells. The tumor has a slight predilection for the male sex, the average age at presentation is 35 years, and the most common symptoms are dyspnea on exertion and signs of cardiac tamponade resulting from a large pericardial effusion (1,3). The chest X-ray is the first tool for the differential diagnosis of dyspnea, followed by echocardiography or chest CT. The chest X-ray shows a varying degree of cardiomegaly and echocardiography reveals a large pericardial effusion with a pericardial mass of variable size, and therapeutic or diagnostic pericardiocentesis yields a large quantity of bloody pericardial effusion, but pericardial fluid analysis usually fails to reveal malignant cells (1-3). As in our case, generalized symptoms, including fever, cough, chest pain, and fatigue, may occur without any pericardial mass being seen on imaging studies; this poses a diagnostic challenge. Chest CT images of synovial sarcoma show a heterogeneous soft-tissue attenuation mass with pericardial effusion infiltrating into the myocardium and adjacent structures, but it needs to be distinguished from other types of sarcomatoid malignant mesothelioma that have a similar site of origin (1,6,7). A surgical biopsy and then cytogenetic analysis were needed to confirm the diagnosis of pericardial synovial sarcoma in our case, because there are wide diversities in the histopathologic findings and the immunological finding of bcl-2 and CD99-positive is not exclusive to synovial sarcoma (3).

The cytogenetic diagnosis of synovial sarcoma identifies the presence of the fusion gene SS18-SSX by the reciprocal translocation t(X;18)(p11;q11): specifically, SYT-SSX1 fusion transcript in biphasic synovial sarcoma and SYT-SSX2 fusion transcript in monophasic synovial sarcoma (1,3). No effective treatment strategy has been determined because of the tumor’s rarity and highly aggressive behavior, which results in a median survival of 25 months (1,2). Complete excision or near total removal was feasible in only 17–22.7% of the reported cases, and adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy are recommended for residual or recurrent tumors (1,2,8,9). The most frequently encountered clinical picture of pericardial synovial sarcoma involves shortness of breath, signs of cardiac tamponade, and/or systemic manifestations such as fever, chill, fatigue, and weight loss. Diagnostic approaches, including chest X-ray, echocardiography, and chest CT, reveal cardiomegaly, a pericardial mass of variable size, with pericardial effusion; subsequent surgical biopsy is needed for tissue diagnosis. Nevertheless, two patients with pericardial synovial sarcoma reported in the literature showed cardiomegaly on the chest X-ray, but there was no visible pericardial mass on echocardiography during the initial diagnostic evaluation, as in our case. In one patient, the 11×12 cm2 pericardial mass was detected 2 months later on a follow-up chest CT, while the other patient had pericardial thickening with local pericardial effusion and gadolinium-DTPA late enhancement on cardiac MRI, suggesting pericardial abscess; tissue resected by pericardiectomy was subsequently used to diagnose synovial sarcoma (1,7). A hemorrhagic pericardial effusion or signs of cardiac tamponade could be a diagnostic clue for pericardial malignancy (10). However, our case suggests that pericardial synovial sarcoma may present clinically with various symptoms related to pericardial effusion, including chest pain, dyspnea, and cardiac tamponade, together with systemic symptoms such as fever, chill, and fatigue. The quantity of pericardial effusion is variable and most cases show a pericardial mass, while fewer have no visible mass (2). It may pose a diagnostic challenge when the patient exhibits the systemic symptoms together with a varying degree of pericardial effusion but without a pericardial mass. Furthermore, if there are no elevated inflammatory makers, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP, and white blood cell count, no clinical signs of cardiac tamponade, and the pericardial fluid analysis reveals no bacterial or neoplastic cells, a large amount of non-hemorrhagic pericardial effusion could be diagnosed as idiopathic (10,11). However, as in our patient, non-hemorrhagic recurrent pericardial effusion may occur in an early case of malignant pericardial synovial sarcoma. Therefore, we believe that whenever idiopathic pericarditis is suspected on the basis of a recurrent large amount of non-hemorrhagic pericardial effusion, a rare pericardial malignancy should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

- Yoshino M, Sekine Y, Koh E, et al. Pericardial synovial sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Today 2014;44:2167-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohzeki M, Fujita S, Miyazaki H, et al. A patient with primary pericardial synovial sarcoma who presented with cardiac tamponade: a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med 2014;53:595-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cheng Y, Sheng W, Zhou X, et al. Pericardial synovial sarcoma, a potential for misdiagnosis: clinicopathologic and molecular cytogenetic analysis of three cases with literature review. Am J Clin Pathol 2012;137:142-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Restrepo CS, Vargas D, Ocazionez D, et al. Primary pericardial tumors. Radiographics 2013;33:1613-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burke AP, Cowan DN, Virmani R. Primary Sarcomas of the Heart. Cancer 1992;69:387-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bezerra SG, Brandão AA, Albuquerque DC, et al. Pericardial synovial sarcoma: case report and literature review. Arq Bras Cardiol 2013;101:e103-6. [PubMed]

- Schumann C, Kunze M, Kochs M, et al. Pericardial synovial sarcoma mimicking pericarditis in findings of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cardiol 2007;118:e83-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Van der Mieren G, Willems S, Sciot R, et al. Pericardial synovial sarcoma: 14-year survival with multimodality therapy. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:e41-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anand AK, Khanna A, Sinha SK, et al. Pericardial synovial sarcoma. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2003;15:186-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sagristà-Sauleda J, Mercé J, Permanyer-Miralda G, et al. Clinical clues to the causes of large pericardial effusions. Am J Med 2000;109:95-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ben-Horin S, Bank I, Guetta V, Livneh A. Large symptomatic pericardial effusion as the presentation of unrecognized cancer: a study in 173 consecutive patients undergoing pericardiocentesis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85:49-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]