Metastatic chordoma detected by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration

Case report

A 76 year old female was transferred to the authors’ institution from an outside hospital with back pain and a presacral mass on a background of progressively worsening fecal and urinary incontinence. Although she had a long history of low back pain and mild stress incontinence for approximately 20 years, this had become significantly worse in the previous few months. Furthermore, in the two weeks prior to presentation, she developed new onset faecal incontinence and her back pain became more severe with radiation to her right leg.

Apart from the above, she was otherwise well, had no other past medical or surgical history and was taking no regular medications. Her family history was positive for colorectal cancer. Her physical examination, hematology, biochemistry and urinalysis were all essentially normal.

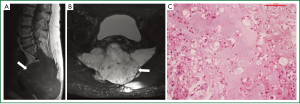

An MRI scan of her abdomen and pelvis revealed a 15 cm mass lesion extending from the lower sacrum inferiorly into the region of the posterior perineum along with extensive bony destruction of the mid and lower sacrum and coccyx (Figure 1A,B). It further showed that mass was causing significant indentation and displacement of the rectum as well as invading the lower spinal canal in the region of the sacrum with involvement of the thecal sac in this area.

A trucut biopsy of the primary mass revealed nests of large vacuolated tumor cells (physaliferous cells) in a prominent extracellular myxoid stroma (Figure 1C). Immunostains showed weak cytoplasmic positivity for S100 protein. The histology and immunohistochemistry were thus consistent with chordoma.

A routine chest x-ray incidentally showed an elevated right hemidiaphragm. A CT thorax further revealed multiple bilateral subcentimetre pulmonary nodules (0.4 to 0.8 cm in diameter) and several enlarged lymph nodes in the right hilum were noted (ranging from 1.1 to 1.4 cm in diameter) as well as a 0.9 cm precarinal node and a 1 cm subcarinal node (Figure 2A). Bronchoscopy and endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) of these nodes was therefore performed.

No endobronchial lesion was apparent. Multiple aspirates were taken from stations 4R, 7 and 11R. Four of six specimens collected showed loose aggregates of vacuolated cells (Figure 2B), which were similar in appearance to the physaliferous cells of the primary specimen (Figure 2A), with associated sarcoid-like reaction (Figure 2C). Hence, the diagnosis of metastatic chordoma was made via EBUS-TBNA. In the evaluations of both the primary tumour and the EBUS-TBNA samples, there was agreement among two pairs of experienced consultant histopathologists, and the diagnosis of metastatic chordoma was facilitated by comparison with the primary tumour. Following discussions at a multidisciplinary team meeting, it was felt that the patient was not a candidate for surgery, and she received palliative radiation therapy. She passed away two months following the diagnosis.

Discussion

Chordomas are rare, slow-growing malignant bone tumors arising from remnants of the notochord (1) They account for 1-4% of primary malignant bone tumours and typically arise in the axial skeleton, most often in the sacrococcygeal region or skull base (spheno-occipital chordoma) (2). These tumors are locally invasive but reported rates of metastasis vary between 10% and 42% of cases, though it has been suggested that misdiagnosis of mucus-producing carcinomas of the rectum as chordomas may have occurred in some chordoma case series (3-5). Metastases to the liver (6), brain (7), heart (8), skin (9), orbit (10) and ovaries (11) have all been reported, with rare documentation of metastases to the lung or mediastinum (12-16). Only two of these thoracic cases utilized cytological aspirates as the means of histological diagnosis: one via transcutaneous fine needle aspiration cytology (12) and one via exfoliative cytology from a sputum sample (13).

Chordomas are characterized by the presence of nests and cords of physaliferous cells in a myxofibrillary stromal background (17). In cytological aspirates, however, these characteristic cells are often absent, revealing only clusters of cells with varying degrees of vacuolation. This makes definitive diagnosis of chordoma difficult as the tumor can mimic other myxoid neoplasms including renal cell carcinomas, myxoid chondrosarcomas, myxoid liposarcomas, metastatic mucinous adenocarcinomas, and myxopapillary ependymomas (18-21). Adjunctive histochemical, immunocytochemical (e.g., cytokeratin, epithelial membrane antigen, vimentin, and S-100 protein), and ultrastructural techniques can assist in the supporting the cytological diagnosis of chordoma, but in aspirates where the characteristic physaliferous cells are absent (unlike in the presented case) a definitive diagnosis of metastatic chordoma requires comparison with histology of the primary tumor (which, in any event, was conducted in the current case) (21). The delay in diagnosis outlined in the current case, to the extreme of having widely metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, likely reflects masking of the slow growth of the chordoma by the long standing history of back pain and stress urinary incontinence.

This is the first case report in the literature of metastatic chordoma diagnosed by EBUS-TBNA. EBUS-TBNA has become an established method for diagnosing mediastinal nodal metastases in lung cancer (22). However, this minimally invasive modality has increasingly been used in the diagnosis of mediastinal metastases of extrathoracic malignancies, including thyroid, renal, oesophageal cancers and rarer tumors such as chondrosarcomas (23-27). Moreover, improvements in adequacy of tissue sampling and specimen handling has allowed EBUS-TBNA specimens to be used, not only for histological and immunocytochemical analyses but also for multiple molecular analyses such as EGFR, ALK and KRAS mutations (28). In spite of these advances, definitive histological diagnosis is often not possible, especially in cases of rare tumors. However, as EBUS technology continues to evolve towards incorporated use of needle forceps and histology needles, the role of EBUS-TBNA in rare thoracic tumor sampling should continue to grow.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chugh R, Tawbi H, Lucas DR, et al. Chordoma: the nonsarcoma primary bone tumor. Oncologist 2007;12:1344-50. [PubMed]

- McMaster ML, Goldstein AM, Bromley CM, et al. Chordoma: incidence and survival patterns in the United States, 1973-1995. Cancer Causes Control 2001;12:1-11. [PubMed]

- Dahlin DC, MacCarthy CS. Chordoma. Cancer 1952;5:1170-8. [PubMed]

- Higinbotham NL, Phillips RF, Farr HW, et al. Chordoma. Thirty-five-year study at Memorial Hospital. Cancer 1967;20:1841-50. [PubMed]

- Chambers PW, Schwinn CP. Chordoma. A clinicopathologic study of metastasis. Am J Clin Pathol 1979;72:765-76. [PubMed]

- Tavernaraki A, Andriotis E, Moutaftsis E, et al. Isolated liver metastasis from sacral chordoma. Case report and review of the literature. J BUON 2003;8:381-3. [PubMed]

- Kamel MH, Lim C, Kelleher M, et al. Intracranial metastasis from a sacrococcygeal chordoma. Case report. J Neurosurg 2005;102:730-2. [PubMed]

- Oda Y, Takada R, Koitabashi K, et al. Isolated cardiac metastasis from sacral chordoma. Jpn Circ J 2000;64:627-30. [PubMed]

- Su WP, Louback JB, Gagne EJ, et al. Chordoma cutis: a report of nineteen patients with cutaneous involvement of chordoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993;29:63-6. [PubMed]

- Konuk O, Pehlivanli Z, Yirmibesoglu E, et al. Compressive optic neuropathy due to orbital metastasis of a sacral chordoma: case report. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2005;21:245-7. [PubMed]

- Zukerberg LR, Young RH. Chordoma metastatic to the ovary. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1990;114:208-10. [PubMed]

- Kanthan R, Senger JL. Fine-needle aspiration cytology with histological correlation of chordoma metastatic to the lung: a diagnostic dilemma. Diagn Cytopathol 2011;39:927-32. [PubMed]

- Kawahara E, Kimura A, Akasofu M, et al. Exfoliative cytology of metastatic chordoma appearing in the sputum. A case report. Acta Cytol 1997;41:513-8. [PubMed]

- Park SY, Kim SR, Choe YH, et al. Extra-axial chordoma presenting as a lung mass. Respiration 2009;77:219-23. [PubMed]

- Maynard RB. A case of chordoma with pulmonary metastases. Aust N Z J Surg 1953;22:215-9. [PubMed]

- Agrawal A. Chondroid chordoma of petrous temporal bone with extensive recurrence and pulmonary metastases. J Cancer Res Ther 2008;4:91-2. [PubMed]

- Crapanzano JP, Ali SZ, Ginsberg MS, et al. Chordoma: a cytologic study with histologic and radiologic correlation. Cancer 2001;93:40-51. [PubMed]

- Gupta RK, Arora R, Vashistha R. Chordoma metastatic to the breast diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. A case report. Acta Cytol 1997;41:910-2. [PubMed]

- Naka T, Fukuda T, Chuman H, et al. Proliferative activities in conventional chordoma: a clinicopathologic, DNA flow cytometric, and immunohistochemical analysis of 17 specimens with special reference to anaplastic chordoma showing a diffuse proliferation and nuclear atypia. Hum Pathol 1996;27:381-8. [PubMed]

- Plate KH, Bittinger A. Value of immunocytochemistry in aspiration cytology of sacrococcygeal chordoma. A report of two cases. Acta Cytol 1992;36:87-90. [PubMed]

- Walaas L, Kindblom LG. Fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the preoperative diagnosis of chordoma: a study of 17 cases with application of electron microscopic, histochemical, and immunocytochemical examination. Hum Pathol 1991;22:22-8. [PubMed]

- Yasufuku K, Chiyo M, Koh E, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound guided transbronchial needle aspiration for staging of lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2005;50:347-54. [PubMed]

- Tournoy KG, Govaerts E, Malfait T, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle biopsy for M1 staging of extrathoracic malignancies. Ann Oncol 2011;22:127-31. [PubMed]

- Chow A, Oki M, Saka H, et al. Metastatic mediastinal lymph node from an unidentified primary papillary thyroid carcinoma diagnosed by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Intern Med 2009;48:1293-6. [PubMed]

- Nakajima T, Yasufuku K, Wong M, et al. Histological diagnosis of mediastinal lymph node metastases from renal cell carcinoma by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirology 2007;12:302-3. [PubMed]

- Noh KW, Wallace MB, Pascual JM, et al. Fine-needle aspiration of peritumoral lymph nodes in esophageal cancer with endobronchial ultrasound. Endoscopy 2006;38:953. [PubMed]

- Nakajima T, Yasufuku K, Suzuki M, et al. Histological diagnosis of spinal chondrosarcoma by endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Respirology 2007;12:308-10. [PubMed]

- Nakajima T, Yasufuku K. How I do it--optimal methodology for multidirectional analysis of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration samples. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6:203-6. [PubMed]