|

Original Article

CT signs, patterns and differential diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura

Cardinale Luciano1, Ardissone Francesco2, Volpicelli Giovanni3, Solitro Federica1, Fava Cesare1

1Institute of Radiology, University of Turin, San Luigi Gonzaga Hospital, Orbassano 10043, Turin, Italy. 2Thoracic Surgery Unit, University of Turin, San

Luigi Gonzaga Hospital, Orbassano 10043, Turin, Italy. 3Department of Emergency Medicine, San Luigi Gonzaga Hospital, Orbassano 10043, Turin, Italy.

Corresponding author: Cardinale Luciano, MD, University of Turin, Institute of Radiology,

San Luigi Gonzaga Hospital, Regione Gonzole 10, Orbassano 10043, Turin, Italy. Tel: +39

011 902640, Fax: +39 011 902640. E-mail: luciano.cardinale@gmail.com

|

|

Abstract

First described by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931, solitary fibrous tumour of the pleura (SFTP) is a mesenchymal tumour that tends to involve

the pleura, although it has also been described in other thoracic areas (mediastinum, pericardium and pulmonary parenchyma) and in extrathoracic

sites (meninges, epiglottis, salivary glands, thyroid, kidneys and breast). SFTP usually presents as a peripheral mass abutting the

pleural surface, to which it is attached by a broad base or, more frequently, by a pedicle that allows it to be mobile within the pleural cavity.

A precise preoperative diagnosis can be arrived at with a cutting-needle biopsy, although most cases are diagnosed with postoperative histology

and immunohistochemical analysis of the dissected sample. SFTP, owing to its large size or unusual locations (paraspinal, paramediastinal,

intrafissural), can pose interpretation problems or, indeed, point towards a diagnosis of diseases of a totally different nature.

We present computed tomography (CT) features of SFTP in patients who had had surgical resection in order to discover any specific CT

findings that might help in the diagnosis of these tumors.

Key words

CT; pleura; SFTP; fibrous tumour

J Thorac Dis 2010;2:21-25. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.02.01.012

|

|

Clinical and pathologic signs

Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura (SFTP), first described as a

distinct clinical entity by Klemperer and Rabin in 1931 ( 1), is a

mesenchymal neoplasm which usually involves the pleura, but it

can occur in other thoracic areas (mediastinum, pericardium, and

lung) as well as in extra-thoracic areas (meninx, epiglottis, salivary

glands, thyroid, kidneys and breast) ( 2, 3). SFTP occurs with equal

frequency in both sexes and is more commonly found in the fourth,

fifth, and sixth decades of life ( 4). Most of the patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis,

and SFTP is discovered only on routine roentgenograms of the

chest. In the remaining patients, the most common clinical symptoms

are chest pain, cough and dyspnea ( 5, 6). SFTP may occur in

benign and malignant forms, these latter showing locally invasive

properties or relapsing after surgical resection. Pre-operative diagnosis can be obtained by a transthoracic cutting

needle biopsy, but in most cases only pathological evaluation

of the resected specimen supported by immunoreactivity of neoplastic cells for CD34 or CD99 allows confirmatory diagnosis

( 5, 7). Concerning microscopic features, the most common architectural

pattern is the so-called“patternless pattern”, in which spindle

cells with bland ovoidal vesicular nuclei, scarce cytoplasm, and

connective tissue are arranged in a random pattern characterized by

a combination of alternating hypocellular and hypercellular areas.

In the second most common pattern, tumor cells lie in close contiguity

with irregular branching small vessels that result in a hemangiopericytoma-

like appearance. Hyper-cellular areas may alternate

with hypo-cellular fibrous areas, hemorrhagic, mixoid or necrotic

areas ( 8). Tumor cells are immunoreactive for CD34 and CD99, also

are variably positive for Bcl-2; usually cytokeratins and desmin

are negative ( 9). The purpose of this paper is to discuss computed tomography

(CT) appearance of Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. We also

discuss differential diagnostic considerations and pitfalls in diagnostic

CT imaging.

|

|

Computed tomography (CT)

The chest computed tomography (CT) scan is the key examination,

which more clearly shows the size and location of the tumor

and aids in surgical planning.

Both the benign and malignant varieties of SFTP usually appear

as well-delineated, often lobulated masses.

CT findings are strictly dependent on tumor size.

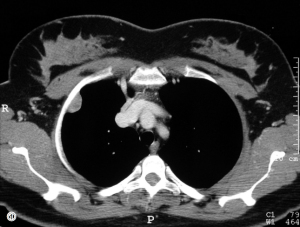

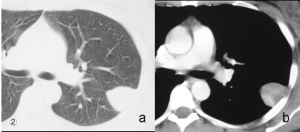

In case of small SFTP, CT more frequently typically demonstrates

a homogeneous well-defined, non-invasive, lobular, soft-tissue mass, adjacent to the chest wall or within a fissure, showing an

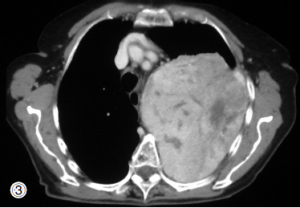

obtuse angle with the pleural surface ( Fig 1, 2) ( 10). Larger lesions are typically heterogeneous and may not exhibit

CT features suggestive of pleural tumors ( Fig 3). Such lesions usually

form acute angles with the adjacent pleural surface mimicking

a subpleural pulmonary mass that could be misdiagnosed as peripheral

lung cancer ( 5). Dedrick et al. stated that a “smoothly tapering angle”of the tumor

with the adjacent pleura (seen in 5 of their 6 cases) was a

highly characteristic finding that could help in establishing the

pleural location of the masses ( Fig 4) ( 11). SFTP have been reported to exhibit intermediate to high attenuation

on unenhanced CT scans. This attenuation has been attributed

to the high physical density of collagen and the abundant capillary

network within these lesions ( 5). Intralesional calcifications (punctate, linear or coarse) are constantly

associated with areas of necrosis and more easily seen in

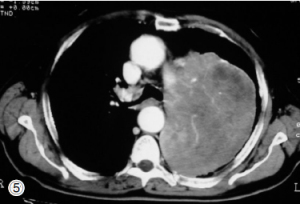

larger lesions ( 5, 10). In case of large masses, enhancement after contrast medium is

typically intense and heterogeneous with central areas of low atten

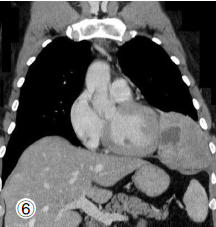

uation (Fig 5, 6). Such intralesional geographic pattern has been

shown to correlate with myxoid changes and areas of hemorrhage,

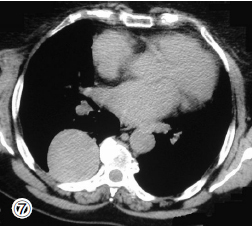

necrosis, or cystic degeneration ( 3, 10, 12). The mass effect of large lesions may produce atelectasis and

displacement of brochi and vessels, but there should be no evidence

of invasion into the lung or chest wall, nor multiple pleural

seed ing. The lesions may grow to be very large, almost filling a

hemithorax ( Fig 7). The preoperative differential diagnosis that arises in a patient

with a SFTP is essentially that of any mass lesion in the chest,

ranging from carcinoma of the lung to various intrapleural sarco

mas ( 14). The usual well-circumscribed appearance of the SFTP

generally rules out malignant pleural mesothelioma since the latter

invariably consists of multiple scattered pleural masses or is a more

diffuse mass encasing the lung. The differential diagnosis becomes more difficoult when SFTP develops in particular sites, thus increasing the number of possible

diagnoses.

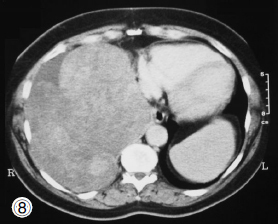

First of all, when located in the paraspinal area, SFTP may appear

indistinguishable from neurogenic tumours ( Fig 8). In these

cases, it is important to evaluate the ribs: chest wall involvement

by SFTP is rare ( 5) and usually manifests as sclerosis or cortical

ero sion at the costal level, a feature more typical of tumours of

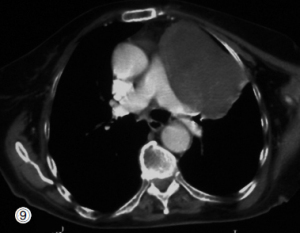

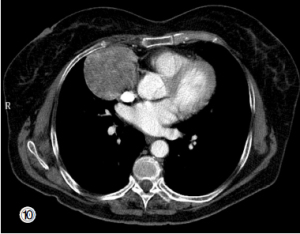

neurogenic origin ( 5). SFTP that have a mediastinic pleural origin can mimic a medistinal

neoplasm; differential diagnosis from a true mediastinal tumor

is sometimes impossible ( Fig 9, 10). Furthermore, multiplanar and volumetric reformatted CT im

ages are crucial in the differential diagnosis of SFTP originating

from the mediastinal pleura, which may mimic a thymic or a germ

cell tumor.

In such cases, analysis of the mediastinum structures is also

fundamental. In fact, in lesions of pleural origin, the mediastinum

is compressed and dislocated, contrary to what occurs in the presence

of a mediastinal mass (which expands, compressing the pulmonary parenchyma without causing mediastinal shift)

( 12, 13, 14, 15). Moreover three-dimensional CT angiography could

be helpful in the accurate evaluation of the blood supply and in detecting

the origin of SFTP. Tumours located within the fissural space may also be interpreted

as pulmonary masses when they appear totally surrounded by

pulmonary parenchyma. Use of thin-slice multidetector CT with

multiplanar reconstructions allows better visualisation of the fissure

and its relationship with the tumour. Likewise, CT findings of fissural

tails with obtuse tumour- fissure angles and a lentiform shape

of tumor could correctly indicate a fissure originated SFTP ( 16).

|

|

Conclusions

SFTP are discovered incidentally on chest radiographs of

asymptomatic patients.

The pre-operative CT differential diagnosis of any mass lesion

of the chest ranges from the carcinoma of the lung to various intrapleural

sarcomas and pleural mesothelioma, but SFTP should also be considered.

The usual well-circumscribed appearance of the SFTP mass

generally rules out malignant pleural mesothelioma since the latter

invariably consists of multiple scattered pleural masses or a more

diffuse mass encasing the lung.

A posterior paraspinal location might suggest a neurogenic tumor,

while a more anterior and para-mediastinal location might

raise the possibility of a thymic neoplasm, germ cell tumor, or teratoma.

When SFTP reaches a large size the diagnosis should be considered

on respect to the absence of local invasion, lymphadenopathy,

or metastatic spread in patients usually presenting in good health.

|

|

References

- Klemperer P, Rabin CB. Primary neoplasm of the pleura: a report of five cases. Arch Pathol 1931;11:385-412.

- Hanau CA, Miettinen M. Solitary fibrous tumor: histological and immunohistochemical

spectrum of benign and malignant variants presenting at different sites.

Hum Pathol 1995;26:440-9.[LinkOut]

- de Perrot M, Fischer S, Brundler MA, Sekine Y, Keshavjee S. Solitary fibrous tumors

of the pleura. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;74:285-93.[LinkOut]

- Kim HJ, Lee HK, Seo JJ, Shin JH, Jeong AK, Lee JH, et al. MR imaging of solitary

fibrous tumors in the head and neck. Korean J Radiol 2005;6:136-42 .[LinkOut]

- Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Abbott GF, McAdams HP, Franks TJ, Galvin JR. Localized

fibrous tumors of the pleura. Radiographics 2003;23:759-83.[LinkOut]

- Mahesh B, Clelland C, Ratnatunga C. Recurrent localized fibrous tumor of the

pleura. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;82:342-5.[LinkOut]

- Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. World health organization classification of tumours.

Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. IARC Press. Lyon

2002.

- Yousem SA, Flynn SD. Intrapulmonary localized fibrous tumor. Am J Clin Pathol

1988;89:365-9.[LinkOut]

- Clayton AC, Salomao DR, Keeney GL, Nascimento AG. Solitary fibrous tumor: a

study of cytologic features of six cases diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration. Diagn

Cytopathol 2001;25:172-6.[LinkOut]

- Ferretti GR, Chiles C, Choplin RH, Coulomb M. Localized benign fibrous tumors

of the pleura. AJR 1997;169:683-6.[LinkOut]

- Dedrick CG, McLoud TC, Shepard JAO, Shipley RT. Computed tomography of

localized pleural mesothelioma. AJR 1985;144:275-80.[LinkOut]

- Cardinale L, Allasia M, Ardissone F, Borasio P, Familiari U, Lausi P, et al. CT

features of solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura: experience in 26 patients. Radiol

Med 2006;111:640-50.[LinkOut]

- Cardinale L, Cortese G, Familiari U, Perna M, Solitro F, Fava C. Fibrous tumour

of the pleura (SFTP): a proteiform disease. Clinical, histological and atypical radiological patterns selected among our cases. Radiol Med 2009;114:204-15.[LinkOut]

- Robinson LA. Solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura. Cancer Control 2006;13:264-9.[LinkOut]

- Cardinale L, Ardissone F, Garetto I, Marci V, Volpicelli G, Solitro F, et al. Imaging

of benign solitary fibrous tumor of the pleura (SFTP): a pictorial essay. Rare

Tumors 2010;2:e1.[LinkOut]

- Chong S, Kim TS, Cho EY, Kim J Kim H. Benign localized fibrous tumour of the

pleura: CT features with histopathological correlations. Clinical Radiology 2006;61:875-82.[LinkOut]

Cite this article as: Luciano C, Francesco A, Giovanni V, Federica S, Cesare F. CT signs, patterns and differential diagnosis of solitary fibrous tumors of the pleura. J Thorac Dis 2010;2:21-25. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.02.01.012

|