Incidental pulmonary nodule management in Canada: exploring current state through a narrative literature review and expert interviews

Introduction

Background

Pulmonary nodules are well-circumscribed opacities in the lung, measuring under 3 cm in diameter (1,2). Incidental pulmonary nodules (IPNs) are asymptomatic nodules detected by imaging performed to investigate unrelated symptoms or conditions and are detected outside of a lung cancer screening program. IPNs are found in approximately one-third of all chest computed tomography (CT) scans (3).

Rationale and knowledge gap

Many IPNs are benign and do not require further investigation (4,5). However, approximately 4% of IPNs progress to early-stage lung cancer within two years (3). IPNs are responsible for more early-stage lung cancer diagnoses than CT screening, even in jurisdictions with well-established lung cancer screening (6,7). Prompt IPN diagnosis is critical to detect lung cancer early and improve survival (5,8-11). While biopsies can evaluate larger IPNs, many IPNs are too small to accurately characterize radiographically and are not amenable to invasive testing (4,11). In these cases, surveillance with serial imaging is required to assess for malignancy (4,12,13). However, there is currently no available evidence on the current state of IPN management across Canada.

Objective

The recent increase in CT imaging in Canada (14) has led to additional IPN detection, highlighting the importance of ensuring standardized, equitable IPN management processes (15). We sought to describe the current state of IPN management in Canada through a narrative literature review and interviews with Canadian key opinion leaders (KOLs) with IPN expertise to identify barriers to optimal management and opportunities for improvement. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review and COREQ reporting checklists (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-23-1453/rc).

Methods

Narrative literature review

The primary research question of this review was “What are the current IPN management standards, processes, and practices in Canada and internationally?”. This question was defined using the Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, and Study type (PICOS) framework (Table 1).

Table 1

| Criteria | Description |

|---|---|

| Population | IPN identified patients (outside of a lung cancer screening program) and/or patients diagnosed with lung cancer having had IPNs as the initial finding (discovered outside of a lung cancer screening program) |

| Intervention/comparator | Not applicable |

| Outcomes | Patient pathway: |

| • Incidence/prevalence/rate of IPN discovery | |

| • Patient demographics and clinical characteristics at time of IPN discovery (including risk factors) | |

| • Source of IPN detection (when/how/where/who) | |

| • Diagnostic tests at time of detection of IPN | |

| • Time between first scan and potential diagnosis of IPN | |

| • Time to treatment and type of treatments for IPN | |

| • Rates and types of subsequent testing/investigations | |

| • Route of follow-up | |

| • Follow-up responsibility (i.e., who is accountable/most responsible provider) | |

| • Rates of loss to follow-up | |

| Definition/IPN classification: | |

| • IPN definition/classification (i.e., nodule size, appearance) | |

| Guidelines and systems used in Canada: | |

| • List of guidelines and systems used in Canada (local and international) for IPN management | |

| • Provider understanding or awareness of IPN management guidelines and adherence to guidelines/systems | |

| Patient clinical and economic outcomes as a result delayed/inadequate IPN management: | |

| • Incidence of lung cancer development | |

| • Lung cancer staging (proportion of stage I–IV cancer diagnoses) | |

| • Survival rate | |

| • Time to lung cancer progression | |

| • Lung cancer mortality rates and all-cause mortality | |

| • Cost of IPN management (per patient) and cost of follow-up (per patient) | |

| • Other relevant clinical and economic outcomes | |

| Reported unmet needs for IPN management in Canada: | |

| • Barriers to patients follow-up in Canada and reasons for inappropriate IPN management | |

| • Other IPN management obstacles and (if reported) recommendations for patient management in Canada | |

| Initiatives/activities launched outside of Canada: | |

| • Recommendations, methods used, and lessons learned | |

| Study type | Observational studies of any type, real-world data studies, diagnostic/treatment guidelines, reviews, expert opinion pieces, government, or KOL-led whitepapers |

PICOS, Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, and Study type; IPN, incidental pulmonary nodule; KOL, key opinion leader.

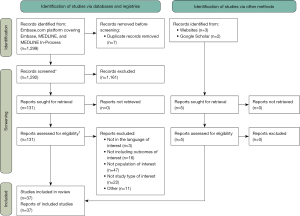

A structured search strategy (Appendix 1, Table S1) was developed to find articles published from January 1, 2010 to November 22, 2023 in Embase, MEDLINE, and MEDLINE In-Process using combinations of the following search terms, including but not limited to: incidental pulmonary nodule, incidental findings, lung parenchyma nodule, computed tomography, clinical pathway, consensus development, treatment, management, patient care, and patient outcome (Table 2). The search was originally conducted on August 6, 2021, and was updated on November 22, 2023 (Table 2). The search was limited to full-text articles in English language. Observational studies, real-world data studies, case studies and reports, diagnostic and treatment guidelines, reviews, expert opinion pieces, and government or KOL-led whitepapers were examined. For unpublished studies, manual searches of conference proceedings and registries were performed (Appendix 1, Table S2). Three KOLs also shared additional relevant studies (Figure 1) (16).

Table 2

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | Originally on 6 August 2021 and updated search on 22 November 2023 |

| Databases and other sources searched | Embase, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process, conference proceedings, and registries |

| Search terms used | Incidental finding or incidental findings |

| Lung or pulmonary or incidental lung nodule or incidental pulmonary nodule or incidental nodule | |

| Lung nodule or lung parenchyma nodule or pulmonary nodule | |

| Multiple or solitary | |

| Lung nodule or pulmonary nodule or pulmonary nodule or pulmonary nodules or lung nodule or lung nodules | |

| CT or computed tomography or computer assisted tomography or scan or CT scan | |

| Clinical pathway | |

| Clinical pathway or clinical protocol | |

| Clinical protocol or consensus | |

| Consensus or consensus development | |

| Consensus development or consensus workshop or clinical practice | |

| Practice or treatment or management or clinical or current practice guideline or recommendation or standard or algorithm | |

| Patient or care or current | |

| Pathway or journey or algorithm or management or practice | |

| Standard or integrated or multidisciplinary or streamlined | |

| Care or patient care or pathway or journey or algorithm or treatment or management | |

| Process or method or quality or patient outcome | |

| Optimization or improvement or management or control or healthcare quality | |

| Animal/exp not human/exp | |

| Timeframe | 2010–2023 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria: observational studies of any type, real-world data studies, case studies/reports, diagnostic/treatment guidelines, reviews, expert opinion pieces, government or KOL-led whitepapers, English language |

| Exclusion criteria: randomized controlled trials, non-randomized controlled trials, single arm trials, letters/editorials, other languages | |

| Selection process | J.S. and L.Z. conducted the study selection and obtained consensus |

CT, computed tomography; KOL, key opinion leader.

Data analysis

Two researchers extracted data in parallel. To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the extracted data, an independent reviewer quality-checked the data by reviewing 20% of extractions. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus among the reviewers. The results of the review were summarized descriptively and presented as a narrative review.

KOL interviews

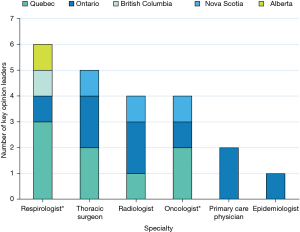

Canadian KOLs were interviewed to further understand current IPN identification and management pathways in Canada and identify opportunities for improvement. Targeted specialists included radiologists, respirologists, thoracic surgeons, epidemiologists, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and primary care physicians (PCPs) given their involvement in the care pathway of patients with IPNs. Potential participants were identified by professional networks and snowball sampling was used for recruitment, starting with leaders within the Canadian Association of Thoracic Surgeons, the Canadian Society of Thoracic Radiology, the Canadian Thoracic Society, and Lung Cancer Canada. Participants were invited to participate in the study via email (up to four emails were sent to one person over 10 weeks). KOLs were contacted until the following conditions were met: at least 20 participants; at least one participant from each of Western Canada, Central Canada, Quebec, and Atlantic Canada and at least two participants from each of the following specialties: radiology, respirology, thoracic surgery, oncology, and primary care. A discussion guide based on the literature review results facilitated an open-ended discussion (Appendix 1). This was pilot tested with the first two participants. Audiovisual recording, field notes, and transcription of the 1.5-hour qualitative interviews were conducted between December 2021 and May 2022. No repeat interviews were conducted, and transcripts were not returned to interviewees. Figure 2 presents the steps for participant selection, interview process, and analysis.

Data analysis

The literature review provided a theoretical foundation for the analysis of interview data. A qualitative thematic analysis was conducted based on a priori concepts highlighted in the literature review (17). This method was chosen as it is most suitable for describing, analyzing, and reporting themes and patterns in data (18). In line with the methods set out by Braun and Clarke [2006], three researchers identified relevant themes, or patterned responses within the interview transcripts, that captured important elements of the research question (19). The thematic analysis was conducted manually, without relying on digital coding or data management software. As an initial step, all interviews were recorded and transcribed for analysis. Each interview was summarized, consolidating and streamlining the key conceptual findings to facilitate subsequent analysis. This also allowed analysts to familiarize themselves with the dataset and begin to identify potential themes (17).

Initial themes were identified, primarily based on the literature review results. Researchers were instructed to remain open to emergent concepts and novel perspectives that arose directly from the interview data, enhancing the richness and depth of the analysis. To enhance credibility and reliability of results, three KOLs critically reflected on the data analysis to identify potential discrepancies or alternative interpretations (20). Following their validation of the analysis for consistency with data, no new themes emerged, indicating that data saturation was reached (Figure 2) (21). Further discussions with KOLs provided an opportunity to refine and condense the initially emergent themes into the major themes identified.

Narrative literature review

Our search identified 1,299 publications via databases and registries and 5 records from manual search. After deduplication and eligibility assessment, 37 studies were included (Figure 1). Most publications were observational studies (n=28) and conducted in the United States (US) (n=33). The search identified only four studies (22-25) conducted in Canada. Given the paucity of relevant Canadian literature, we included studies from both the US and Canada to provide contextually relevant findings for North American healthcare settings, and to draw on the available US literature evidence where most of the relevant research has been conducted.

Summary of review findings

IPN detection rates vary based on index diagnostic imaging, which can include chest, abdominal, whole-body CTs, or coronary CT angiography and can be ordered by various specialists for a range of patient presentations (22,23,26-33). Variability in IPN reporting exists. Radiology reports may be incomplete (26), resulting in diagnostic delays due to requests for additional review or misinterpretation (34,35).

When an IPN is identified, patient management is affected by guideline awareness and clinical judgement. In Canada, the Fleischner Society guidelines are well recognized by radiologists and used extensively for IPN management. These guidelines utilize the initial probability of malignancy (determined by factors such as nodule size, patient age, and smoking history or other risk factors) to establish appropriate schedules and duration for radiographic follow-up (36). However, varying degrees of guideline conformance exist amongst radiologists, and conformance is higher in academic settings and in group practices that include a subspecialist thoracic radiologist (37-39). Compared to those who received guideline-concordant care, the median time to lung cancer diagnosis in the US was longer in patients with less intensive evaluation of IPN (40). Conversely, more intensive evaluation has been associated with greater expenditures, higher radiation exposure, and more procedure-related adverse events (40,41).

US studies have shown that many patients with IPNs did not receive appropriate imaging and clinical follow-up (29,30,42-47). Similarly, up to two thirds of patients in Canada did not receive follow-up imaging in the recommended time frame, even when radiologists adhered to the Fleischner Society guidelines (22-24,30). Factors associated with timely follow-up imaging for IPNs include explicit mention in a hospital discharge summary, attending an outpatient follow-up visit, younger patient age, and inclusion of the nodule in the impression section (not just the findings section) of the radiology report (23,30).

In addition to suboptimal follow-up of nodules, studies also identified a lack of adherence to guidelines. Reduced adherence to guidelines may occur due to lack of continuity or coordination in care and information overload (24). To overcome this issue and improve patient management, some centers have implemented clinical decision support tools (48), electronic consultation systems (25), and patient risk questionnaires administered at the time of CT (49).

KOL interviews

Twenty KOLs from five Canadian provinces agreed to participate (Figures 2,3). Three major themes emerged from the interviews including variability in radiology reporting of IPNs, suboptimal communication, and variability in guideline adherence and patient management. Supporting quotations from the KOLs are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

| Themes | KOL participants quotations |

|---|---|

| Theme one: variability in radiology reporting of IPNs | KOL 2: “In my experience, radiologists did not want to collect a lot of data, they were too busy to collect a lot of data and want everything trimmed down and record/describe them in minimal details to avoid a big workload. And so the issue is that sometimes they may see things that their gut reaction might tell them is not a problem and do not report it properly. So, if that process was smoothed out and made more mandatory and made to be known to be good practice to insist nodules are followed up.” |

| KOL 3: “By setting up the framework and establish [sic] the management protocol, the CT screening protocol, the reporting standard and we would change the overall management of lung cancer that way.” | |

| KOL 11: “There’s no standardized reporting for incidental nodules.” | |

| KOL 14: “There is a need to improve the overall consistency and reducing the variability around the standards of radiology reporting. I think there is there’s [sic] variability and [sic] reporting standards and there’s variability in radiologists.” | |

| KOL 14: “I think that there are some regions that are more organized than others and in a need to [sic] and as we even see within our region some variability between the community and the academic center in between radiologists. Standardize the radiology reporting between the community and the academic center in terms of the thresholds that a radiologist uses to report something as being suspicious for malignancy.” | |

| Theme two: suboptimal communication | KOL 11: “I think in Halifax or in Nova Scotia, they have you know, the radiologist just like in breast screening has the ability to actually order or schedule you know [sic] a follow up, whereas in other jurisdictions in certainly in [sic] Ontario, I don’t have that ability.” |

| Regarding communication systems: | |

| KOL 7: “The radiologist report, and their recognition is very important ‘cause [sic] often they’ll tell the doctor, you know, recommend CT scan in six months and that might save the system and the patient a lot of hassle of sending the patient for pulmonary or thoracic or PET scan or all these things because the radiologist just says it’s a low risk and this is what you should do.” | |

| KOL 9: “Things to make that more robust or automated would be great.” | |

| Regarding guidelines: | |

| KOL 19: “Based on what it seems to me like [sic] they’re deciding based on what it looks like as opposed to necessarily having a lot of history of the patient.” | |

| Theme three: variability in guideline adherence and patient management | KOL 4: “But there’s also patient factors. Uhm, [sic] there’s a much higher incidence of lung cancer diagnosis among people who live in rural areas compared to urban, a much higher propensity if you come from a lower income bracket, your health literacy.” |

| KOL 5: “It should then go back to the person that ordered this scan and the family doctor, but again, some of those lines are dotted, not straightened. It can all fall apart there. Most of the time, the referring physician would be responsible to read the report and refer to an appropriate place. In certain jurisdictions, Ontario and increasingly across the country there is.” | |

| KOL 12: “Lack of staffing time to manage. Lack of staffing and time. I think in radiology departments, it’s probably difficult to get.” | |

| KOL 14: “The importance is to get patients with IPNs to a specialist pathway where you would hope that the adherence to guidelines would be better if not perfect.” |

KOL, key opinion leader; IPN, incidental pulmonary nodule; CT, computed tomography; PET, positron emission tomography.

Theme one: variability in radiology reporting of IPNs

The experts agreed that there is a lack of radiology report standardization in Canada for the documentation and description of IPNs, such that there is significant variability even within institutions. Due to this heterogeneity, thoracic surgeons and respirologists noted that they personally review images to guide decision-making while considering the radiologist report. The experts also noted barriers to widespread implementation of standardized reporting. One radiologist felt that their senior department members are less likely to change the way they report findings and would not comply with a standardized form.

PCPs and respirologists expressed that radiology reports often lack appropriate guidance on recommended follow-up intervals, and medical oncologists stated that there is often a lack of guideline adherence in the reports. A non-radiologist, who also has extensive research in lung cancer screening, highlighted that IPNs may be missed entirely by the reviewing radiologist, or the radiologist may choose not to report all nodules. The radiologists also agreed with this point. Radiologists noted that inconsistent efforts to obtain and inconsistent availability of prior imaging also contributes to the variability in reporting. This process poses challenges in certain jurisdictions, where logistical constraints or limited access to previous imaging studies hinder the ability to accurately assess temporal evolution of IPNs. This has been documented in the literature (50). KOLs noted that in some provinces, all publicly funded imaging is available on a single imaging network, but in other provinces, nearby hospitals use separate imaging networks making comparison with prior imaging cumbersome.

Theme two: suboptimal communication between radiologist and ordering physician, between healthcare providers, and with patients

Radiologists expressed frustration that physicians requesting CTs often do not communicate adequate clinical information to suggest IPN management. For example, the Fleischner Society guidelines for management and follow-up of IPNs require knowledge of the patient’s risk of lung cancer (e.g., smoking history) and do not apply to patients with known malignancies (4,51). Radiologists noted that this information is rarely included on requisitions, limiting the ability to provide specific surveillance recommendations.

Experts agreed that standardized communication between physicians can ensure appropriate and collaborative follow-up. Several radiologists, respirologists, and thoracic surgeons noticed a disconnect in communication between the patient, the ordering physician, and the radiologist. One radiologist estimated that 30–40% of patients with small IPNs and 5% of patients with more concerning lesions are lost to follow-up. A Canadian chart review supports this estimate, finding that 27% of patients with IPNs are lost to follow-up (49). PCPs noted the risk of patients being lost to follow-up due to the large volume of tests requiring action. Radiologists noted the absence of processes to confirm whether their recommendations are followed.

Radiologists, respirologists, and thoracic surgeons suggested that automated communication could avoid communication breakdown between physicians. In some healthcare settings, patients with high-risk nodules may be automatically referred by radiology to a rapid assessment or lung nodule clinic to initiate work-up. One health jurisdiction provides a follow-up CT appointment embedded within the initial radiology report (49). Similarly, two radiologists praised Rapid Investigation Clinics that have improved IPN management. Such clinics use tracking systems to minimize delays in care and include multidisciplinary investigation and rapid access to diagnostic procedures as well as treatment (52). However, the experts noted that most jurisdictions do not have similar established clinics or pathways.

The experts highlighted the heterogeneity of systems across Canadian provinces and the lack of provincially integrated, privacy-compliant electronic medical records as key barriers for the implementation of standardized and automated communication and tracking systems. Radiologists were the only specialty that suggested the adoption of a tracking system. All specialties agreed that a closed-loop communication tool would be beneficial. One PCP, however, was concerned that automated notifications would be too frequent.

Finally, some experts expressed concerns about patients not adhering to recommended follow-up imaging due to suboptimal communication between physicians and patients or suboptimal imaging appointment communication; however, this theme was not fully explored during the interviews. Additionally, a few KOLs raised the issue of shared decision making with patients regarding their care plan and the importance of patient education and empowerment in ensuring timely IPN follow-up, though this theme was not prominent in the KOL interviews and not further explored.

Theme three: variability in guideline adherence and patient management

While several specialists agreed on the importance of considering individual clinical factors and patient preferences when managing IPNs, many experts also expressed concerns regarding both over and under investigation of IPNs resulting from lack of awareness, adherence, or conformity with guideline-recommended care. This lack of guideline adherence was thought to relate in part to unclear or suboptimal guidelines. All thoracic radiologists interviewed stated that they employ Fleischner Society guidelines to inform their recommendations for managing IPNs. However, they noted that the guidelines may be vague or not applicable for some nodules. Experienced radiologists noted that they exercise their own judgment and deviate from the guidelines based on their expertise in interpreting clinical history and IPN characteristics. General radiologists or clinicians who are not specialized in lung disease were less familiar with Fleischner Society guidelines. Meanwhile, several specialists noted that referral pathways in Canada are non-standardized and vary by jurisdiction, further leading to inconsistencies in patient care.

The experts expressed concern that patients from low socioeconomic status and rural areas are at higher risk of suboptimal management and being lost to follow-up. Socioeconomic status is linked to health literacy and some patients are more likely to experience barriers to adhering to recommended follow-up. This is particularly relevant for lung cancer diagnosis given that people who live in rural and remote communities experience inequities in cancer risk, access to care, and outcomes (53).

A summary of key initiatives and recommendations from the interviewed KOLs is presented in Table 4. Additional items that arose which did not relate to the major themes included: patient education and outreach, multidisciplinary collaboration, involvement of nurse navigators, and lack of staffing, time, and resources.

Table 4

| Key initiatives and recommendations | Summary of the key recommendations by speciality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radiologists | Respirologists | Thoracic surgeons | Primary care physicians | |

| Standardized radiology reports | Standardized radiology reports should be a priority in initiatives launched | Standardized radiology reports are needed with a level of agreement and consistency in establishing the management protocol and follow-up | Radiology reports should be standardized | Radiology reports should be standardized, and radiologists should provide more guidance for PCPs in the report |

| Adoption of a closed-loop communication tool | Closed-loop communication with automated communication systems | Automatic referral process is needed to track patient’s diagnostic assessments and provide efficient communication between providers | A two-way closed communication loop would be beneficial | Mixed opinions: a closed-loop communication tool would create too many notifications for PCP, but automated systems could improve communication |

| Adoption of a tracking system | A better tracking system is needed to avoid losing patients in follow-up | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Referring the patient to a multidisciplinary nodule clinic | Not enough multidisciplinary clinics due to lack of resources: should only be used for concerning nodules. Many small nodules do not require a multidisciplinary clinic | Multidisciplinary collaboration is valuable for cases that are more difficult to assess and important for physicians who are not used to evaluating a lung nodule | Not a key initiative according to thoracic surgeons | N/A |

| Additional training | Better education is needed on nodule risk stratification and for better awareness/adherence of guidelines | Additional training is needed to ensure standardization of radiology reporting and for practitioners lacking knowledge on IPN management | Additional training is needed especially with radiologists | PCPs need additional training on radiology reports and on how to follow-up each type of nodule |

PCP, primary care physician; N/A, not applicable; IPN, incidental pulmonary nodule.

Clinical implications

Through a narrative literature review and interviews with KOLs, we found evidence of suboptimal management of patients with IPNs in Canada, which aligns with international perspectives on IPN management (5). The main opportunities for improvement include inconsistency in radiology reporting of IPNs, inadequate communication (between healthcare providers and between healthcare providers and patients), and variability in patient management pathways. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing the Canadian landscape of IPN management from a multidisciplinary perspective with insights on regional heterogeneity.

The addition of a qualitative component to our review allowed a richness of data that would not have been available through chart reviews or other clinical research. While the KOL interviews were structured to obtain personal clinical experience and opinion, rather than quantitative data, many of the KOL opinions are supported by the literature. For example, the frustration noted by the radiologist KOLs regarding clinical information that is insufficient to allow specific IPN management recommendations mirrors multiple publications documenting poor requisitions as a contributor to medical error (50,54-56). Expanded use of electronic medical records may help solve some of the issues regarding missing information on radiology requisitions by automatically populating the missing fields (57). This could be further explored as an area for improvement.

Several opportunities for improvement identified in this study have also been identified in other countries, where efforts and initiatives to improve IPN management have demonstrated promising results. For example, US studies show that using structured radiology reports can reduce missing information and significantly improve follow-up care (33,34,58,59). Interviewed experts agreed that standardized radiology reports would be beneficial and highlighted success where implemented. In Canada, the use of standardized radiology reporting is usually at the discretion of the individual radiologist (50). Implementation of standardized radiology reporting at a larger scale across the country may be supported by non-radiologist physicians.

The KOLs supported strategies to facilitate follow-up and monitoring of patients with IPNs, such as implementation of closed-loop communication and tracking systems. A US single-center retrospective study using the Radiology Result Alert and Development of Automated Resolution tracking system showed that the interactive system facilitates follow-up by engaging the ordering physician in the follow-up process and relieving some administrative burden (59). One radiology department in Canada has implemented an automatic CT booking program for nodules that require follow-up CT but do not currently need a referral to a specialist (49).

This study highlights the significant variability that exists in Canadian healthcare pathways as healthcare delivery remains a provincial and territorial mandate. Therefore, implementation of standardized processes and referral pathways at multiple levels could reduce variability and optimize IPN management. For example, a standardized interdisciplinary triage and diagnostic pathway implemented at a health region in Ontario for patients undergoing evaluation for suspected lung cancer, including those with IPNs, improved the efficiency of a rapid assessment clinic and timeliness of care and diagnosis (60).

Moreover, the results highlight the challenges of adhering to existing lung nodule guidelines in Canada, due to a lack of awareness, adherence, or conformity with guideline-recommended care. Thoracic radiologists are guided by Fleischner Society recommendations, but note their inapplicability to certain patient populations, and potential differences in interpretation of the recommendations that lead to deviations based on individual expertise. The lack of familiarity with these guidelines among some general radiologists and non-specialized clinicians, coupled with non-standardized referral pathways that vary by jurisdiction, contribute to inconsistencies in patient care. Understanding and addressing these barriers to guideline implementation are essential for optimal IPN management and should be explored in future research.

In considering improvement strategies, initiatives to improve IPN management should be well-integrated into the current administrative/information technology ecosystem and must be easy to use. Challenges include heterogeneity of systems across Canada, barriers to sharing of electronic patient information, and the low prioritization of a perceived less-urgent health issue. However, given the morbidity and mortality associated with lung cancer (61,62), the evidence in favor of early detection of primary lung malignancies (8-11), and the rise in detection of IPNs through increased imaging (15), an opportunity exists to improve the health of Canadians through the implementation, standardization, and dissemination of optimal IPN management processes across the country. Lastly, while the importance of patient education and shared decision making were not featured prominently in our review of the literature or interviews with KOLs, these aspects warrant further investigation when considering improvement opportunities (63).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Despite following a predefined structured protocol to decrease risk of bias, our literature review did not include double-blinded eligibility assessment of all full text reports that were included after screening of titles and abstracts, such that findings may be subject to some bias. While we did not assess the risk of bias of the included studies, this was not the intent in performing a narrative review. Findings from the qualitative interviews were presented descriptively and full data coding was not performed. While most included studies in the literature review were conducted in the US, the KOLs expressed that many of the IPN management concerns in other countries apply to Canada as well. The paucity of literature specific to the Canadian landscape highlights the need for this study. We also note that most experts interviewed were from Ontario and Quebec, such that generalizability of findings within the country is limited. Additionally, we only interviewed two PCPs, both from Ontario, and we did not interview patient representatives. Finally, we did not report findings from the interviews beyond those related to the major themes identified, and these warrant further investigation.

Conclusions

Significant variability exists across Canada in IPN management. Despite available guidelines, there remain barriers to optimal management at all phases of the IPN pathway. We identify the need to facilitate more widespread use of standardized radiology reporting to guide the management of IPNs, to improve communication processes between healthcare providers and patients, and to ensure consistency in IPN management pathways. Future research should aim to develop recommendations for implementation of initiatives that address these identified needs to optimize the management of patients with IPNs across Canada.

Acknowledgments

Paola Marino and Danielle Guy, employees from Amaris Consulting, provided medical writing support. Petar Atanasov, employee from Amaris Consulting, provided valuable review and feedback.

Funding: This work was supported by

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review and COREQ reporting checklists. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-23-1453/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-23-1453/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-23-1453/coif). G.C.D., J.H., and D.M. received unrestricted support for meetings, planning and data collection, manuscript writing and editing, participating in a working group, and consulting fees from AstraZeneca. J.S. and L.Z. were employees of Amaris Consulting at the time of conduction of this study, which is a paid consultancy to AstraZeneca to support the conduction of this study. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Kim TJ, Kim CH, Lee HY, et al. Management of incidental pulmonary nodules: current strategies and future perspectives. Expert Rev Respir Med 2020;14:173-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trinidad López C, Delgado Sánchez-Gracián C, Utrera Pérez E, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules: characterization and management. Radiologia (Engl Ed) 2019;61:357-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gould MK, Tang T, Liu IL, et al. Recent Trends in the Identification of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:1208-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacMahon H, Naidich DP, Goo JM, et al. Guidelines for Management of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules Detected on CT Images: From the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology 2017;284:228-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmid-Bindert G, Vogel-Claussen J, Gütz S, et al. Incidental Pulmonary Nodules - What Do We Know in 2022. Respiration 2022;101:1024-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Osarogiagbon RU, Liao W, Faris NR, et al. Lung Cancer Diagnosed Through Screening, Lung Nodule, and Neither Program: A Prospective Observational Study of the Detecting Early Lung Cancer (DELUGE) in the Mississippi Delta Cohort. J Clin Oncol 2022;40:2094-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhou N, Deng J, Faltermeier C, et al. The majority of patients with resectable incidental lung cancers are ineligible for lung cancer screening. JTCVS Open 2023;13:379-88. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bradley SH, Kennedy MPT, Neal RD. Recognising Lung Cancer in Primary Care. Adv Ther 2019;36:19-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Birring SS, Peake MD. Symptoms and the early diagnosis of lung cancer. Thorax 2005;60:268-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lam S, Bryant H, Donahoe L, et al. Management of screen-detected lung nodules: A Canadian partnership against cancer guidance document. Can J Respir Crit Care Sleep Med 2020;4:236-65.

- Sánchez M, Benegas M, Vollmer I. Management of incidental lung nodules <8 mm in diameter. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:S2611-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Simon M, Zukotynski K, Naeger DM. Pulmonary nodules as incidental findings. CMAJ 2018;190:E167. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- LeMense GP, Waller EA, Campbell C, et al. Development and outcomes of a comprehensive multidisciplinary incidental lung nodule and lung cancer screening program. BMC Pulm Med 2020;20:115. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dowhanik SPD, Schieda N, Patlas MN, et al. Doing More With Less: CT and MRI Utilization in Canada 2003-2019. Can Assoc Radiol J 2022;73:592-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adams SJ, Babyn PS, Danilkewich A. Toward a comprehensive management strategy for incidental findings in imaging. Can Fam Physician 2016;62:541-3.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lochmiller CR. Conducting Thematic Analysis with Qualitative Data. Qual Rep 2021;26:2029-44.

- Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being 2014;9:26152. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006;3:77-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sundler AJ, Lindberg E, Nilsson C, et al. Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nurs Open 2019;6:733-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are We There Yet? Data Saturation in Qualitative Research. Qual Rep 2015;20:1408-16.

- Leung C, Shaipanich T. Current Practice in the Management of Pulmonary Nodules Detected on Computed Tomography Chest Scans. Can Respir J 2019;2019:9719067. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kwan JL, Yermak D, Markell L, et al. Follow Up of Incidental High-Risk Pulmonary Nodules on Computed Tomography Pulmonary Angiography at Care Transitions. J Hosp Med 2019;14:349-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- You JJ, Laupacis A, Newman A, et al. Non-adherence to recommendations for further testing after outpatient CT and MRI. Am J Med 2010;123:557.e1-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Walker D, Macdonald DB, Dennie C, et al. Electronic Consultation Between Primary Care Providers and Radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2020;215:929-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bates R, Plooster C, Croghan I, et al. Incidental Pulmonary Nodules Reported on CT Abdominal Imaging: Frequency and Factors Affecting Inclusion in the Hospital Discharge Summary. J Hosp Med 2017;12:454-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ekeh AP, Walusimbi M, Brigham E, et al. The prevalence of incidental findings on abdominal computed tomography scans of trauma patients. J Emerg Med 2010;38:484-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goehler A, McMahon PM, Lumish HS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of follow-up of pulmonary nodules incidentally detected on cardiac computed tomographic angiography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Circulation 2014;130:668-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alpert JB, Fantauzzi JP, Melamud K, et al. Clinical significance of lung nodules reported on abdominal CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;198:793-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blagev DP, Lloyd JF, Conner K, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and the radiology report. J Am Coll Radiol 2014;11:378-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Scholtz JE, Lu MT, Hedgire S, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules in emergent coronary CT angiography for suspected acute coronary syndrome: Impact of revised 2017 Fleischner Society Guidelines. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2018;12:28-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammerschlag G, Cao J, Gumm K, et al. Prevalence of incidental pulmonary nodules on computed tomography of the thorax in trauma patients. Intern Med J 2015;45:630-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDonald JS, Koo CW, White D, et al. Addition of the Fleischner Society Guidelines to Chest CT Examination Interpretive Reports Improves Adherence to Recommended Follow-up Care for Incidental Pulmonary Nodules. Acad Radiol 2017;24:337-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aase A, Fabbrini AE, White KM, et al. Implementation of a Standardized Template for Reporting of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules: Feasibility, Acceptability, and Outcomes. J Am Coll Radiol 2020;17:216-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Barjaktarevic I, Arenberg D, Grimes BS, et al. Indeterminate Pulmonary Nodules: How to Minimize Harm. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2016;37:689-707. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MacMahon H, Austin JH, Gamsu G, et al. Guidelines for management of small pulmonary nodules detected on CT scans: a statement from the Fleischner Society. Radiology 2005;237:395-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg RL, Bankier AA, Boiselle PM. Compliance with Fleischner Society guidelines for management of small lung nodules: a survey of 834 radiologists. Radiology 2010;255:218-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gould MK, Altman DE, Creekmur B, et al. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Pulmonary Nodules Detected Incidentally or by Screening: A Survey of Radiologist Awareness, Agreement, and Adherence From the Watch the Spot Trial. J Am Coll Radiol 2021;18:545-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rampinelli C, Cicchetti G, Cortese G, et al. Management of incidental pulmonary nodule in CT: a survey by the Italian College of Chest Radiology. Radiol Med 2019;124:602-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Farjah F, Monsell SE, Gould MK, et al. Association of the Intensity of Diagnostic Evaluation With Outcomes in Incidentally Detected Lung Nodules. JAMA Intern Med 2021;181:480-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosenkrantz AB, Xue X, Gyftopoulos S, et al. Downstream Costs Associated with Incidental Pulmonary Nodules Detected on CT. Acad Radiol 2019;26:798-802. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iaccarino JM, Steiling K, Slatore CG, et al. Patient characteristics associated with adherence to pulmonary nodule guidelines. Respir Med 2020;171:106075. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ridge CA, Hobbs BD, Bukoye BA, et al. Incidentally detected lung nodules: clinical predictors of adherence to Fleischner Society surveillance guidelines. J Comput Assist Tomogr 2014;38:89-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hammer MM, Kapoor N, Desai SP, et al. Adoption of a Closed-Loop Communication Tool to Establish and Execute a Collaborative Follow-Up Plan for Incidental Pulmonary Nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2019;212:1077-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moseson EM, Wiener RS, Golden SE, et al. Patient and Clinician Characteristics Associated with Adherence. A Cohort Study of Veterans with Incidental Pulmonary Nodules. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2016;13:651-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee JS, Lisker S, Vittinghoff E, et al. Follow-up of incidental pulmonary nodules and association with mortality in a safety-net cohort. Diagnosis (Berl) 2019;6:351-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pyenson BS, Bazell CM, Bellanich MJ, et al. No Apparent Workup for most new Indeterminate Pulmonary Nodules in US Commercially-Insured Patients. J Health Econ Outcomes Res 2019;6:118-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu MT, Rosman DA, Wu CC, et al. Radiologist Point-of-Care Clinical Decision Support and Adherence to Guidelines for Incidental Lung Nodules. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:156-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borgaonkar J, Manos D, Miller R, et al. The Fleischner Society’s recommendations for the follow up of CT detected pulmonary nodules: A program to optimize their implementation. Poster session presented at: European Congress of Radiology - European Society of Thoracic Imaging (ESTI) 2012; 2012 Jun 22; London, UK.

- Walker M, Borgaonkar J, Manos D. Managing Incidentalomas Safely: Do Computed Tomography Requisitions Tell Us What We Need to Know? Can Assoc Radiol J 2017;68:387-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nair A, Devaraj A, Callister MEJ, et al. The Fleischner Society 2017 and British Thoracic Society 2015 guidelines for managing pulmonary nodules: keep calm and carry on. Thorax 2018;73:806-12.

- Ezer N, Navasakulpong A, Schwartzman K, et al. Impact of rapid investigation clinic on timeliness of lung cancer diagnosis and treatment. BMC Pulm Med 2017;17:178. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canadian Partnership Against Cancer. Lung Cancer and Equity: A Focus on Income and Geography [Internet]. Ontario, Canada; [cited 2022 Dec 2]. Available online: https://s22457.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Lung-cancer-and-equity-report-EN.pdf

- Munk PL. The Holy Grail--The Quest for Reliable Radiology Requisition Histories. Can Assoc Radiol J 2016;67:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fatahi N, Krupic F, Hellström M. Quality of radiologists' communication with other clinicians--As experienced by radiologists. Patient Educ Couns 2015;98:722-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Obara P, Sevenster M, Travis A, et al. Evaluating the Referring Physician's Clinical History and Indication as a Means for Communicating Chronic Conditions That Are Pertinent at the Point of Radiologic Interpretation. J Digit Imaging 2015;28:272-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Geeslin MG, Gaskin CM. Electronic Health Record-Driven Workflow for Diagnostic Radiologists. J Am Coll Radiol 2016;13:45-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Dann E, et al. Using radiology reports to encourage evidence-based practice in the evaluation of small, incidentally detected pulmonary nodules. A preliminary study. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:211-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang SK, Doshi AM, Recht MP, et al. Process Improvement for Communication and Follow-up of Incidental Lung Nodules. J Am Coll Radiol 2020;17:224-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mullin MLL, Tran A, Golemiec B, et al. Improving Timeliness of Lung Cancer Diagnosis and Staging Investigations Through Implementation of Standardized Triage Pathways. JCO Oncol Pract 2020;16:e1202-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brenner DR, Poirier A, Woods RR, et al. Projected estimates of cancer in Canada in 2022. CMAJ 2022;194:E601-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2022 [Internet]. Canadian Cancer Society; 2022. Available online: https://cancer.ca/en/research/cancer-statistics

- Karazivan P, Dumez V, Flora L, et al. The patient-as-partner approach in health care: a conceptual framework for a necessary transition. Acad Med 2015;90:437-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]