Safety of long-term esophageal stent use for multiple indications

Highlight box

Key findings

• Over a 10-year period with 90 esophageal stents placed, long term stent use (>30 days) did not result in increased rates of stent related complications. The most common complication was stent migration and there were no instances of erosion into the aorta or esophageal perforation. As stent dwell time increased, complications related to stenting decreased.

What is known and what is new?

• Long-term (>30 days) use of esophageal stents remains controversial, mainly due to previous studies detailing significant complications with long term use.

• In this study, we observed that long-term use of esophageal stents for both benign and malignant indications did not result in increased rates of stent-related complications.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Long-term esophageal stent use for both benign and malignant esophageal disease may be associated with fewer complications than previously suggested. Future studies should examine the ideal stent dwell time for specific indications and attempt to identify preoperative risk factors that may be associated with life-threatening stent complications such as tracheoesophageal and aortoesophageal fistula development.

Introduction

Esophageal stents have been used for decades to safely treat many different disease processes, including esophageal perforation, inoperable esophageal cancer, esophageal strictures, and esophageal fistulas (1-5). Initially hollow tubes were used in the 1800s to treat malignant esophageal strictures (1). Since then, stent technology has improved significantly and their use for benign esophageal strictures has also increased. However, stents have traditionally been used only for short periods (<30 days of dwell time), with stent removal at 2–4 weeks after insertion (1-4). Long-term use (>30 days of dwell time) of stents for any indication remains controversial, in part due to previous studies detailing significant complications with long-term use (3,6). Numerous studies have documented severe complications associated with long-term esophageal stent use including tracheoesophageal fistulas, stent erosion, and aortoesophageal fistulas (7-9). However, outside of the United States (US), there are societal recommendations for long-term use of esophageal stents for specific indications (4,10). Some US centers, including ours, use long-term esophageal stents more frequently, with few major complications seen.

Here we present a retrospective review of esophageal stents placed for any indication over the last decade. This study’s objective was to investigate stent complications associated with long-term esophageal stent use at a single institution by a single service. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-366/rc).

Methods

Consecutive patients undergoing initial esophageal stent placement for any indication (example ICD10 codes: 530.3, 530.5, C15.9, K22.3, K22.2, T82.539A) by the Thoracic Surgery Division were included in this retrospective review who had at least 30 days of follow-up after initial stent placement. Our institutional practice is such that only the Thoracic Surgery Division consistently attempts to keep esophageal stents for longer than 30 days. Inclusion in this study required the initial stents to have been placed between June 1st, 2010, and June 1st, 2020. Patients were not followed after July 1st, 2020. Patients with initial stents placed at outside institutions, or by any other medical or surgical division were excluded. All patients had a Merit Medical EndoMAXX (Merit Medical; Jordan, UT, USA) fully covered esophageal stent placed, stent diameter (19 or 23 mm) and length (120 or 150 mm) were selected at the discretion of the surgeon. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The UMass Chan Medical School Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study (No. H00020938) of esophageal stent use for any indication and waived individual patient consent for this study. Patients with multiple stent placements were included.

Patients were subdivided by benign or malignant indications. Benign indications were considered: spontaneous esophageal perforations, traumatic esophageal perforations, post-operative anastomotic leak, benign esophageal strictures, tracheoesophageal fistula. Malignant indications were defined as: malignant esophageal stricture and tracheoesophageal fistula secondary to malignancy. Outcomes included intra-operative complications, post-procedure complications, stent-related complications, patient outcomes, total number of stents placed, and length of time stent was in place. Procedural complications were defined as occurring within 24 hours of stent placement. Stent-related complications were defined as stent migration, dysphagia, reflux, persistent cough, continued anastomotic leak, stent/esophageal obstruction, esophageal perforation, tracheoesophageal fistula, and aortoesophageal fistula. Other complications that occurred past 24 hours following stent placement were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome of this study was the length of time an esophageal stent was in place. Secondary outcomes included any stent-related complication and need for further intervention. Descriptive statistics of patient-based, stent-based, and indication-based demographics reported continuous variables as median [interquartile range (IQR)], while categorical variables are listed as number [frequency (%)]. Bivariate analysis of stent indication used Fisher’s exact and Wilcox rank sum for categorical and continuous variables. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for statistical tests. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata 16 (College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Demographics and stent related issues

Fifty-six consecutive patients met inclusion criteria, with 25 patients having two or more stents placed (Table 1). There was no patient who had a delayed stent removal because of noncompliance or other reasons. Over 70% of the included patients were male (Table 1). Ninety esophageal stents were placed during the study period (Table 2). The median length of time a stent remained in place was 59 (IQR, 21–105) days (Table 2). All stents were placed without intra-operative complications during the study period. One patient suffered from epigastric pain immediately following stent placement, this occurred twice, following two different stent placements. Both times this pain was managed conservatively and resolved shortly after each of the two stents were placed allowing for the stents to remain in place without issue. Complication rates between short-term (<30 days) and long-term (>30 days) stents were not significantly different (P=0.39). No instances of esophageal perforation or aortoesophageal fistulas related to stents were identified during the study period. There was one instance of broncho-esophageal fistula diagnosed 12 days after stent placement for a post-esophagectomy anastomotic leak that developed 7 weeks after Ivor Lewis esophagectomy. This fistula was managed with repeat stenting, and subsequently resolved completely after 5 months of stenting. This patient had regular follow-ups over the ensuing 1.5 years and there was no recurrence of the fistula.

Table 1

| Variables | Study population (n=56) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 15 (26.8) |

| Male | 41 (73.2) |

| Age (years) at initial stent placement | 65 [57–71] |

| Multiple stents placed | 25 (44.6) |

| Stent indication | |

| Benign | 35 (62.5) |

| Malignant | 21 (37.5) |

| Indication for initial stent | |

| Anastomotic leak | 12 (21.4) |

| Anastomotic stricture | 2 (3.6) |

| Benign esophageal stricture | 7 (12.5) |

| Esophageal perforation | 12 (21.4) |

| Malignant obstruction | 17 (30.4) |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula | 2 (3.6) |

| Other | 4 (7.1) |

| Further treatment required | 23 (41.1) |

| Final outcome | |

| Alive | 21 (37.5) |

| Dead | 26 (46.4) |

| Unknown | 9 (16.1) |

| Initial procedural complications | |

| Epigastric pain | 1 (1.8) |

| None | 55 (98.2) |

| Initial stent complications | |

| Stent migration | 14 (25.0) |

| Esophageal perforation | 0 (0.0) |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula | 1 (1.8) |

| Aortoesophageal fistula | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 7 (12.5) |

| None | 34 (60.7) |

| Other complications (n=7) | |

| Persistent anastomotic leak | 1 (14.3) |

| Persistent productive cough | 1 (14.3) |

| Dysphagia | 2 (28.6) |

| Obstruction | 2 (28.6) |

| Reflux | 1 (14.3) |

| Length of time stent was in place (days) | |

| Stent 1 | 59 [21–119] |

| Stent 2 | 59 [13–90] |

| Stent 3 | 105 [22–150] |

| Stent 4 | 102 [35–167] |

| Stent 5 | 42 [–] |

Categorical variables reported as n (%), while continuous variables are reported as median [IQR]. IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2

| Variables | Stent based demographics (n=90) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 23 (25.6) |

| Male | 67 (74.4) |

| Age (years) at stent placement | 62 [56–70] |

| Benign or malignant indication | |

| Benign | 61 (67.8) |

| Malignant | 29 (32.2) |

| Indication for stent | |

| Anastomotic leak | 15 (16.7) |

| Anastomotic stricture | 8 (8.9) |

| Benign esophageal stricture | 18 (20.0) |

| Esophageal perforation | 16 (17.8) |

| Malignant obstruction | 24 (26.7) |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula | 6 (6.7) |

| Other | 3 (3.3) |

| Stent dwell time (days) | 59 [21–105] |

| Patient status | |

| Alive | 39 (43.3) |

| Dead | 38 (42.2) |

| Unknown | 13 (14.4) |

| Procedural complications | |

| Epigastric pain | 2 (2.2) |

| None | 88 (97.8) |

| Stent complications | |

| Stent migration | 23 (25.6) |

| Esophageal perforation | 0 (0.0) |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula | 1 (1.1) |

| Aortoesophageal fistula | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 14 (15.6) |

| None | 52 (57.8) |

| Other complications (n=14) | |

| Persistent anastomotic leak | 1 (7.1) |

| Persistent productive cough | 1 (7.1) |

| Dysphagia | 6 (42.9) |

| Obstruction | 3 (21.4) |

| Reflux | 3 (21.4) |

Categorical variables reported as n (%), while continuous variables are reported as median [IQR]. IQR, interquartile range.

Stent indication

Of the 90 stents placed, 61 were placed for benign indications and 29 were placed for malignant indications (Table 3). The median length of time that a stent remained in place for benign indications was 60 (IQR, 22–103) days, while stents placed for malignant indication remained in place for 57 days (IQR, 21–135 days, P=0.81) (Table 3). Stent migration was the most common complication and occurred more in patients with benign indications, although not significantly (P=0.12) (Table 3). Overall, stents placed for benign reasons had a significantly higher rate of any complication as compared to stents placed for malignant indications (P=0.02) (Table 3). Stents placed for benign esophageal stricture disease (benign esophageal strictures and anastomotic strictures) had a median stent dwell time of 72 (IQR, 22–149) days and had significantly higher rates of stent migration (P<0.001) compared to all other stent indications (Table 4). Benign stricture disease had significantly higher rates of any stent-related complications (69.2%, P=0.002) compared to all other stent indications (Table 4). However, if we remove stent migrations from the calculation of any stent-related complications, then the stent-related complication rate would drop to 26.7% (compared to 47.4% including stent migrations), which is not statistically significant when compared to all other indications (P>0.99).

Table 3

| Variables | Benign indication (n=61) | Malignant indication (n=29) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61 [57–70] | 65 [56–70] | 0.70 |

| Sex | 0.18 | ||

| Female | 13 (21.3) | 10 (34.5) | |

| Male | 48 (78.7) | 19 (65.5) | |

| Length of time stent was in place (days) | 60 [22–103] | 57 [21–135] | 0.81 |

| Stent complication | |||

| Stent migration | 19 (31.1) | 4 (13.8) | 0.12 |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| Esophageal perforation | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Aortoesophageal fistula | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Other | 11 (18.0) | 3 (10.3) | 0.54 |

| None | 30 (49.2) | 22 (75.9) | 0.02 |

| Any complication | 31 (50.8) | 7 (24.1) | 0.02 |

Continuous variables reported as median [IQR], categorical variables reported as n (%). IQR, interquartile range.

Table 4

| Variables | All other indications (n=64) | Benign stricture disease (n=26) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63 [56–70] | 60 [56–72] | 0.56 |

| Sex | 0.06 | ||

| Female | 20 (31.3) | 3 (11.5) | |

| Male | 44 (68.8) | 23 (88.5) | |

| Length of time stent was in place (days) | 57 [21–103] | 72 [22–149] | 0.56 |

| Stent complication | |||

| Stent migration | 9 (14.1) | 14 (53.8) | <0.001 |

| Tracheoesophageal fistula | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| Esophageal perforation | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Aortoesophageal fistula | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – |

| Other | 10 (15.6) | 4 (15.4) | >0.99 |

| None | 44 (68.8) | 8 (30.8) | 0.002 |

| Any complication | 20 (31.3) | 18 (69.2) | 0.002 |

Continuous variables reported as median [IQR], categorical variables reported as n (%). IQR, interquartile range.

Stent dwell time

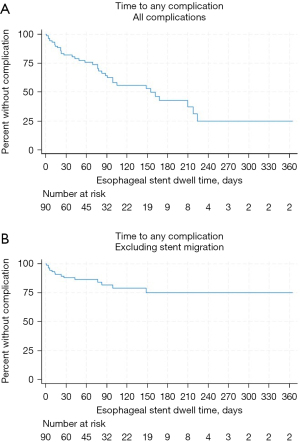

When comparing stents by their length of stent dwell time in 2-week intervals, there were no significant differences in rates of complications (Table 5). There was no significant difference between the median age or sex in any of the stent dwell groups (Table 5). Similarly, there was no significant difference in stent indications, either benign or malignant. Half of the population had stents in place without complications at 60 days of stent dwell time (Figure 1). There were no complications associated with stent removal during the study period, no matter the duration of stent dwell time.

Table 5

| Variables | Stent present ≤14 days |

Stent present 15–30 days |

Stent present 31–44 days |

Stent present 45–59 days |

Stent present ≥60 days |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | P value | Value | P value | Value | P value | Value | P value | Value | P value | |||||

| Total number of stents | 16 | – | 16 | – | 6 | – | 7 | – | 45 | – | ||||

| Age (years) | 61 [57–69] | 0.66 | 62 [55–69] | 0.68 | 63 [48–73] | 0.78 | 63 [60–72] | 0.48 | 62 [56–70] | 0.68 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 7 (43.8) | 0.11 | 4 (25.0) | >0.99 | 1 (16.7) | >0.99 | 0 (0.0) | 0.18 | 11 (24.4) | >0.99 | ||||

| Male | 9 (56.3) | 12 (75.0) | 5 (83.3) | 7 (100.0) | 34 (75.6) | |||||||||

| Length of time stent remained in place (days) | 7 [4–12] | – | 22 [21–28] | – | 38 [36–41] | – | 51 [48–57] | – | 105 [86–168] | – | ||||

| Stent indication benign or malignant | ||||||||||||||

| Benign | 10 (62.5) | 0.77 | 12 (75.0) | 0.57 | 5 (83.3) | 0.66 | 3 (42.9) | 0.21 | 31 (68.9) | >0.99 | ||||

| Malignant | 6 (37.5) | 4 (25.0) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (57.1) | 14 (31.1) | |||||||||

| Stent complications | ||||||||||||||

| Stent migration | 1 (6.3) | 0.06 | 4 (25.0) | >0.99 | 1 (16.7) | >0.99 | 2 (28.6) | >0.99 | 15 (33.3) | 0.15 | ||||

| Aortoesophageal fistula | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | 0 (0.0) | – | 0 (0.0) | – | 0 (0.0) | – | ||||

| Esophageal perforation | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | 0 (0.0) | – | 0 (0.0) | – | 0 (0.0) | – | ||||

| Tracheoesophageal fistula | 1 (6.3) | 0.18 | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 | ||||

| Any stent complication | 9 (56.3) | 0.27 | 6 (37.5) | 0.78 | 2 (33.3) | >0.99 | 2 (28.6) | 0.69 | 19 (42.2) | >0.99 | ||||

Continuous variables reported as median [IQR], categorical variables reported as n or n (%). IQR, interquartile range.

Discussion

Stent related complications are traditionally thought to be associated with length of stent dwell time (1,3,7,8). However, we found that long-term esophageal stenting, defined as stent use for longer than 30 days, does not result in increased rates of stent related complications in a cohort of patients receiving esophageal stents for multiple indications, with the caveat that this series does not have enough power to provide a comparative analysis. The most common stent-related complication reported was stent migration, which occurred 23 times (25.6% of stents). The majority of patients did not experience any complication (60.7% by patient, 57.8% by stent). Although benign stent indications had a significantly higher rate of any complication (P=0.02) compared to malignant indication, there was no significant difference in stent migration rates between the two groups (P=0.12). We believe that benign disorders show a trend towards higher though not statistically significant stent migration because many of these either do not have a constricted area helping to keep the stent in place (leaks, perforations), or these constrictions dilate over time (benign strictures); whereas malignancies which are stented palliatively usually maintain this constriction. Importantly, this study found no instances of aortoesophageal fistulas or esophageal perforations due to esophageal stent placement. The one broncho-esophageal fistula noted was diagnosed 2 weeks after stenting for an anastomotic leak. This fistula was managed with long-term repeat stenting to cover it from the esophageal side, and the fistula closed after a 5-month stent dwell time.

A previous study investigating esophageal stents placed only for intra-thoracic esophageal perforation or anastomotic leak found ideal stent dwell times of 4 and 2 weeks respectively (6). This study found a reduction in stent-related complications when stent dwell time was decreased (6). However, the study cohort differed from our cohort significantly, as did the type of stents used. Another study found no significant association between stent dwell time and complicated stent removal, with uncomplicated stent removal having a median stent dwell time of 39 days compared with 29 days in the complicated removal group (11). Even when adjusting for stent type, they found there was no association between stent dwell time and complicated removal (11). Similarly, we found no association between length of stent dwell time and any stent related complication or complication related to stent removal in our study population. Other studies of esophageal stents have recommended dwell times anywhere from 2 to 12 weeks for benign perforations, strictures, anastomotic leaks or esophageal fistulas (4,10,12). The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) actually recommends an ideal dwell time of 6–8 weeks for benign esophageal strictures, with a maximum dwell time of 12 weeks (4,10). However, this is classified as a strong recommendation with low quality evidence. While there have been no randomized control trials to study the optimal stent dwell time for benign esophageal strictures, it is believed that prolonged (>30 days) stent dwell time can lead to stricture/scar remodeling and is safe for use in patients (1,4,10,13).

The overall complication rate in this study was similar to previously reported complication rates of 21–53% (4,10,14-16). The most common stent-related complication was stent migration, again confirming that this fairly benign adverse event is a frequent complication of esophageal stent use. However, if stent migration was removed from the overall stent-based complication rate, then our overall complication rate would be 16.7%, instead of 42.2%. The rate of stent migration found in this study was similar to previously reported rates of 11–28% (4,6,10,17). Interestingly, we found higher rates of stent migration occurring in patients with benign indications for stent placement, contradicting the similar rates of stent migration in benign (23.8%) and malignant (23.9%) conditions in a 2020 study (18). We believe, though could not conclusively prove, that this is because of our low threshold for inserting stents in perforations and leaks. Given our generally favorable experience with prolonged stenting, we would utilize stents early on and not employ conventional methods first (drainage and nil per os) until failure before considering stenting. The ESGE notes that stent migration is very common, occurring nearly 30% of the time, when stenting for benign esophageal strictures, and still highly recommends its use (4,10). The society suggests use of endoscopic suturing or use of over-the-stent clips to reduce this migration rate, a practice which we do not employ but are strongly considering. Overall, the rate of any complication was significantly higher in benign indications, unlike the findings of Essrani et al. (18). Our higher complication rate in benign disorders includes placement of high stents for very proximal strictures, leading to some cases of patient intolerance. In contrast, for high malignant strictures we would typically insert feeding tubes and allow radiation to resolve the malignant obstruction. We had no findings of aortoesophageal fistula creation or esophageal perforations due to stent use. These low rates of major stent related complications resemble previous reports, and provide additional evidence to the safety of esophageal stent use, especially with long-term dwell times (17,19,20). Previous studies have highlighted how low-frequency adverse major stent related complications can change esophageal stent practice significantly (8). We had one instance of broncho-esophageal fistula post-esophagectomy which eventually resolved.

There are some limitations to our study. First, our study is retrospective in nature. Second, we report findings from a single tertiary care institution with significant experience with esophageal stent use and retrieval, potentially making it challenging to generalize our findings to other centers. Third, we report only on 56 patients with 90 stent placements and found some statistical significance, but it is possible that our population was not large enough to power other findings. Furthermore, our analysis combines data on stent indications due to the limited number of patients within each group, hindering our ability to draw distinct conclusions for individual indications. We did not control for pre-operative chemotherapy or radiation, which have been previously shown to influence successful stenting. We were also unable to study any quality of life metrics with our patients as our study was retrospective in nature.

While previously reported short-term (<30 days) use of esophageal stents remains a safe option, long-term (>30 days) esophageal stent use is also a viable option for patients. While stent migration remains the most common stent complication, potentially morbid complications like aortoesophageal fistulas were not found in this cohort. Future studies should examine ideal stent dwell times in relation to possible scar/tissue remodeling seen with long-term stent use in benign and anastomotic stricture disease.

Conclusions

Long-term esophageal stent use, defined as stent use for longer than 30 days did not result in increased rates of stent related complications in our study population. Thus, long-term esophageal stent use may be safe for multiple indications. When appropriate, long-term esophageal stents can be indicated for benign esophageal disease, particularly for benign esophageal strictures. Future study should examine pre-operative patient risk factors associated with life-threatening stent-related complications like tracheoesophageal and aortoesophageal fistula development in a multi-institutional cohort study.

Acknowledgments

Deceased author: the authors would like to acknowledge and thank Dr. Bryce M. Bludevich, who was the true force behind the study. She was an essential part of this project from its conception until the very end. The authors mourn her untimely passing before the submission of the manuscript.

Meeting presentation: this work was presented as a Quick Shot presentation at the virtual American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress in October 2021.

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-366/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-366/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-366/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, except for author B.M.B., who is deceased (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-366/coif). K.F.L.U. reports that he holds positions in two local medical societies (Treasurer, Philippine Medical Association of New England and Committee Member, Worcester District Medical Society), which do not impact this work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Dua KS. History of the Use of Esophageal Stent in Management of Dysphagia and Its Improvement Over the Years. Dysphagia 2017;32:39-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- So H, Ahn JY, Han S, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Fully Covered Self-Expanding Metal Stents for Malignant Esophageal Obstruction. Dig Dis Sci 2018;63:234-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herrera A, Freeman RK. The Evolution and Current Utility of Esophageal Stent Placement for the Treatment of Acute Esophageal Perforation. Thorac Surg Clin 2016;26:305-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spaander MC, Baron TH, Siersema PD, et al. Esophageal stenting for benign and malignant disease: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical Guideline. Endoscopy 2016;48:939-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fuccio L, Hassan C, Frazzoni L, et al. Clinical outcomes following stent placement in refractory benign esophageal stricture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy 2016;48:141-8. [PubMed]

- Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Dake M, et al. An Assessment of the Optimal Time for Removal of Esophageal Stents Used in the Treatment of an Esophageal Anastomotic Leak or Perforation. Ann Thorac Surg 2015;100:422-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Whitelocke D, Maddaus M, Andrade R, et al. Gastroaortic fistula: a rare and lethal complication of esophageal stenting after esophagectomy. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;140:e49-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Giannini T, et al. Analysis of unsuccessful esophageal stent placements for esophageal perforation, fistula, or anastomotic leak. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:959-64; discussion 964-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Odell JA, DeVault KR. Extended stent usage for persistent esophageal leak: should there be limits? Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:1707-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spaander MCW, van der Bogt RD, Baron TH, et al. Esophageal stenting for benign and malignant disease: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2021. Endoscopy 2021;53:751-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Halsema EE, Wong Kee Song LM, Baron TH, et al. Safety of endoscopic removal of self-expandable stents after treatment of benign esophageal diseases. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:18-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freeman RK, Ascioti AJ, Wozniak TC. Postoperative esophageal leak management with the Polyflex esophageal stent. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2007;133:333-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dua KS. Expandable stents for benign esophageal disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2011;21:359-76. vii. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bick BL, Song LM, Buttar NS, et al. Stent-associated esophagorespiratory fistulas: incidence and risk factors. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:181-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Parker RK, White RE, Topazian M, et al. Stents for proximal esophageal cancer: a case-control study. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:1098-105. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ross WA, Alkassab F, Lynch PM, et al. Evolving role of self-expanding metal stents in the treatment of malignant dysphagia and fistulas. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:70-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dasari BV, Neely D, Kennedy A, et al. The role of esophageal stents in the management of esophageal anastomotic leaks and benign esophageal perforations. Ann Surg 2014;259:852-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Essrani R, Shah H, Shah S, et al. Complications Related to Esophageal Stent (Boston Scientific Wallflex vs. Merit Medical Endotek) Use in Benign and Malignant Conditions. Cureus 2020;12:e7380. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freeman RK. To stent or not to stent? That is the question. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;154:1151. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liang DH, Hwang E, Meisenbach LM, et al. Clinical outcomes following self-expanding metal stent placement for esophageal salvage. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2017;154:1145-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]