Safety and feasibility of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy combined with immunotherapy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective single-group phase II clinical study

Highlight box

Key findings

• In this study, we verified the efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) combined with immunotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC). Compared with the standard treatment of nCRT, pathologic complete response (pCR) increased from 35% to 42.1% by propensity score matching. The addition of immunotherapy did not increase the toxicity and side effects of treatment.

What is known and what is new?

• Based on the ChemoRadiotherapy for Oesophageal cancer followed by Surgery Study (CROSS) and 5010 trials, nCRT is still the standard of neoadjuvant therapy for ESCC. However, the 10-year follow-up study showed that the distant metastasis rate was still as high as 40%, and the local recurrence rate was 21%. The results showed that remote metastasis was still the main failure mode in the current triple mode of nCRT combined with surgery.

• Based on the results of CROSS and 5010 and the rapid development of immunotherapy, this study combined nCRT with immunotherapy to try to find a new way to improve the pCR of patients and ultimately the survival of patients.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Due to the high distant metastasis rate and local recurrence rate of the triple mode of nCRT combined with surgery, there is an urgent need to explore a new method to improve pCR and long-term survival of patients with operable esophageal cancer, and to conduct phase II or even phase III randomized controlled studies for further verification.

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) ranks 11th in incidence and 7th in mortality rate among all malignant tumors worldwide (1). Although there has been a decline in both incidence and mortality rates, the situation remains severe. Earlier, the ChemoRadiotherapy for Oesophageal cancer followed by Surgery Study (CROSS) group published a study by van Hagen et al. demonstrating that the preoperative chemoradiotherapy treatment for patients with esophageal and esophagogastric cancer has improved survival rates (2). Following the work of the CROSS group, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT) has represented a standard treatment for resectable esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) since 2012. However, a 10-year follow-up study (3) reported that the nCRT group had a distant metastasis rate of 31.5% and a local recurrence rate of 13.8%, indicating that relapse after neoadjuvant therapy is primarily driven by distant metastasis. Furthermore, in another study called the Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy for Esophageal Cancer 5010 (NEOCRTEC5010) randomized clinical trial (4), it was demonstrated that although the nCRT group had a lower recurrence rate compared to the surgery-only group (33.7% vs. 45.8%, P=0.013), they experienced longer periods without local recurrence (P=0.012) and distant metastasis (P=0.028). However, the incidence of distant metastasis remained higher than that of local recurrence in both groups (nCRT group: 23.9% vs. 14.1%; simple operation group: 31.7% vs. 22.5%). These results indicate that the EC recurrence is still predominantly characterized by distant metastasis after surgery. Therefore, the enhancement of systemic control and the optimization of neoadjuvant therapy efficacy are pressing issues that require immediate attention.

Importantly, in recent years, immunotherapy has brought new hope to the treatment and management of locally advanced EC (5). The CheckMate 577 study (6) built upon the NEOCRTEC5010 trial (4), but targeted patients did not achieve pathologic complete response (pCR) after nCRT and were at high risk for recurrence. Their results showed that median disease-free survival (DFS) was significantly prolonged to 22.4 months (compared to 11.0 months in the control group). Additionally, the median survival without distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS) was extended to 28.3 months (in contrast to 17.6 months in the control group). These results demonstrated that there is a promising potential of immunotherapy in the treatment of EC. New findings in a clinical trial by researchers from the University of California San Francisco and the Gladstone Institute show that leaving lymph nodes intact may improve the efficacy of immunotherapy (7). Hence, administering immunotherapy prior to surgery may enhance its effectiveness. At present, there are only a handful of studies on nCRT combined with immunotherapy (nRCIT) for EC. Li et al. (8) conducted the PALACE-1 study in 2021, which included 20 patients with ESCC and evaluated the therapeutic effect of nCRT combined with pembrolizumab (nRCIT). Their results showed that the incidence of grade 3 and above adverse reactions was 65%. The pCR rate of 18 patients who underwent surgery was 55.6%. Also, data from the PERFECT trial (9) showed that the treatment of nCRT combined with Atrezil monoclonal antibody had good compliance, but the pCR rate was only 25%. Although the perfect study failed to repeat the PALACE-1 study for many reasons, the two studies are phase I/II clinical studies, so the sample size is small, but the data are still very valuable. Whether nCRT combined with immunization can really improve the survival benefits of patients after surgery still needs further confirmation. Additionally, in clinical practice, chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy is also used as a neoadjuvant therapy for EC, and the comparative effectiveness of this approach is still unknown. Therefore, a meta-analysis (10) including 38 studies showed that the rates of pCR and major pathologic response (MPR) for the nCRT group and the neoadjuvant chemotherapy group were 38% vs. 28% (P=0.08) and 67% vs. 57% (P=0.18), respectively. Further clarification is still needed through randomized controlled trials. Therefore, based on these preliminary findings, we conducted a phase II clinical study to assess the safety and efficacy of nRCIT for patients diagnosed with locally advanced ESCC (NCT03940001) in 2019. Additionally, propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was employed to ensure comparability between the groups by achieving a 1:1 matching ratio. We present this article in accordance with the TREND reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1279/rc).

Methods

Study design and patient selection

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, China [No. IRB-2023-742(IIT)] and informed consent was taken from all the patients. This single-arm phase II, clinical trial perspective was conducted at Zhejiang Cancer Hospital between January 2019 to December 2021. The inclusion criteria are as follows: (I) histological or cytological evidence of EC. (II) There are lesions that can be measured according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) standards. (III) American Joint Committee on Cancer/Union for International Cancer Control (AJCC/UICC) EC stage (8th edition) clinical stage T2–4aNanyM0, or T1–3N+M0. (IV) Age ≥18 and ≤75 years. (V) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) physical status (PS) score is 0 to 1. (VI) No esophageal perforation or active esophageal hemorrhage; no significant trachea or thoracic vascular invasion. (VII) No previous chest chemotherapy and radiotherapy, immunotherapy, or biotherapy. (VIII) Hemoglobin ≥90 g/L, platelets ≥10×109/L, neutrophil absolute count ≥1.5×109/L. (IX) Serum creatinine ≤1.25× upper limit of normal (UNL) or creatinine clearance ≥60 mL/min. (X) Serum bilirubin ≤1.5 times UNL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) [serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT)] and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) [serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT)] ≤2.5 times UNL, alkaline phosphatase ≤5 times UNL. (XI) No history of interstitial pneumonia or prior interstitial pneumonia. (XII) Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) >1.2 L.

Protocols for neoadjuvant treatment

Patients were administered with two cycles of programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor, sintilimab, at a dose of 200 mg every 3 weeks (Q3W) (3 mg/kg for patients weighing less than 60 kg), in conjunction with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. The chemotherapy regimen comprised platinum-based drugs and paclitaxel (TP regimen). Specifically, paclitaxel (50 mg/m2) and carboplatin [area under the curve (AUC) =2] were intravenously administered on days 1, 8, 15, 22, and 29. External-beam radiation therapy was initiated on day 1 of the chemotherapy. The delivery of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) was conducted using 6 megavoltage (MV) photons for all patients. The radiation target volume was delineated as the involved field with the dose treatment of 41.4 Gy in 23 fractions administered at a rate of 5 fractions per week where each fraction delivered a 1.8 Gy dose. The clinical target volume lymph node (CTV-nd) was defined as the gross tumor volume of the lymph nodes plus a 1 cm margin. A planning target volume (PTV) was generated by applying a 0.5–1 cm margin to the CTV. Cone beam computed tomography (CT) was utilized for weekly verification purposes. Prophylactic irradiation of supraclavicular and mediastinal lymphatic drainage areas, excluding areas 5 and 6, was performed for upper thoracic esophageal carcinoma.

Protocols for surgical procedures

The surgery was routinely performed within 6–8 weeks after nRCIT, with no contraindications for surgical intervention. The surgical procedures including minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE), right transthoracic open esophagectomy, or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) with a total two- or three-field lymphadenectomy were conducted. Gastric tube reconstruction was employed to restore the digestive tract post-esophagectomy. Specifically, extensive lymph node dissection included left recurrent laryngeal nerve, right recurrent laryngeal nerve, paraesophageal, paratracheal, and subcarinal regions. In cases of severe adhesion or intraoperative bleeding, patients were converted to open thoracotomy during the surgical procedure. To ensure optimal surgical quality and safety, all operations were performed by five attending surgeons at our center, each with over 100 cases of experience in EC surgery.

Pathological evaluation

The pathological diagnosis was conducted by two seasoned pathologists. MPR was defined as ≤10% residual tumor cells after neoadjuvant therapy and pCR was defined as the absence of any residual invasive tumor cells.

Statistical analysis

A control group of 53 patients, who had previously received nCRT in Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, was established for PSM analysis. Criteria for inclusion were: age 18–75 years. Histologically confirmed ESCC. ECOG PS 0–1. Clinical staging of ESCC in patients with resectable or potentially resectable T2–4aN0 or T1–4aN+. The length of esophageal lesion was less than 8 cm. There are no surgical contraindications. Patients without complete follow-up information were deleted. These patients received nCRT with a radiotherapy dose of 41.4 to 50.4 Gy, and the radiotherapy technique was IMRT. Chemotherapy with PC regimen was synchronized weekly (paclitaxel 50 mg/m2, carboplatin AUC =2). Surgery was performed 4–6 weeks after completion of nCRT. Telephone follow-up was conducted every 3 months within 2 years after surgery and once a year after 2 years. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Group comparisons were conducted using two independent sample t-tests. Chi-square tests were employed for intergroup comparisons. Fisher’s exact probability method was applied where chi-square test assumptions were not met. The rank sum test of two independent samples was applied to compare count or rank data. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the incidence of adverse events (AEs) across different groups. To address baseline characteristic imbalances between the control and experimental groups, inverse probability-weighted matching was implemented to control for confounding variables in both groups, enabling a comparison and analysis of differences after matching had been achieved. All figures in this study were generated using R language (version 4.1.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) software packages including GGPLOT2 and GGSCI. All statistical tests conducted in this study adopted a two-tailed approach with P≤0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients selection and baseline characteristics

A total of 22 patients diagnosed with thoracic ESCC were initially assessed for eligibility for this work; however, 17 patients ultimately received esophagectomy following nRCIT as shown in Figure 1.

One to one PSM was conducted based on age, sex, tumor location, length, history of alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), clinical T stage, lymph node staging, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging, and cycles of chemotherapy.

Ultimately, a total of 53 patients who received nCRT were successfully matched. The baseline characteristics before and after PSM in the two groups are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Factors | Total (n=70) | Before PSM | After PSM | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nCRT (n=53) | nRCIT (n=17) | P value | nCRT (n=10) | nRCIT (n=10) | P value | |||

| Age (years) | 59.9±7.1 | 59.0±6.4 | 62.6±8.3 | 0.12 | 60.8±6.7 | 61.4±9.2 | 0.87 | |

| Sex | 0.24 | 0.47 | ||||||

| M | 60 (85.7) | 47 (88.7) | 13 (76.5) | 8 (80.0) | 10 (100.0) | |||

| F | 10 (14.3) | 6 (11.3) | 4 (23.5) | 2 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Tumor location | 0.26 | >0.99 | ||||||

| Upper | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Middle | 36 (51.4) | 30 (56.6) | 6 (35.3) | 4 (40.0) | 3 (30.0) | |||

| Lower | 33 (47.1) | 22 (41.5) | 11 (64.7) | 6 (60.0) | 7 (70.0) | |||

| Length (cm) | 0.77 | 0.82 | ||||||

| ≤3 | 7 (10.0) | 5 (9.4) | 2 (11.8) | 3 (30.0) | 1 (10.0) | |||

| 4–6 | 42 (60.0) | 31 (58.5) | 11 (64.7) | 5 (50.0) | 7 (70.0) | |||

| ≥7 | 21 (30.0) | 17 (32.1) | 4 (23.5) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | |||

| Alcohol use | 0.03 | 0.65 | ||||||

| No | 24 (34.3) | 14 (26.4) | 10 (58.8) | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | |||

| Yes | 46 (65.7) | 39 (73.6) | 7 (41.2) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (60.0) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.71 | >0.99 | ||||||

| <24 | 55 (78.6) | 40 (75.5) | 15 (88.2) | 9 (90.0) | 10 (100.0) | |||

| 24–28 | 13 (18.6) | 11 (20.8) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| >28 | 2 (2.9) | 2 (3.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Clinical T staging | 0.08 | >0.99 | ||||||

| 2 | 13 (18.6) | 11 (20.8) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | |||

| 3 | 55 (78.6) | 42 (79.2) | 13 (76.5) | 8 (80.0) | 9 (90.0) | |||

| 4 | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Lymph node staging | 0.001 | 0.003 | ||||||

| 0 | 4 (5.7) | 2 (3.8) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (20.0) | |||

| 1 | 52 (74.3) | 45 (84.9) | 7 (41.2) | 10 (100.0) | 3 (30.0) | |||

| 2 | 14 (20.0) | 6 (11.3) | 8 (47.1) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (50.0) | |||

| TNM staging | 0.07 | 0.63 | ||||||

| II + IIIA | 16 (22.9) | 12 (22.6) | 4 (23.5) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (40.0) | |||

| IIIB | 52 (74.3) | 41 (77.4) | 11 (64.7) | 8 (80.0) | 6 (60.0) | |||

| IVA | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| Cycles of CT | 0.06 | >0.99 | ||||||

| 1–2 | 28 (40.0) | 25 (47.2) | 3 (17.6) | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) | |||

| 3–6 | 42 (60.0) | 28 (52.8) | 14 (82.4) | 7 (70.0) | 8 (80.0) | |||

Data are presented as mean ± SD or n (%). PSM, propensity score matching; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; nRCIT, nCRT combined with immunotherapy; M, male; F, female; BMI, body mass index; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; CT, chemotherapy; SD, standard deviation.

Short-term outcomes

The pCR was 41.2% (7/17) in the nRCIT group and 34.0% (18/53) in the nRCT group, which was not associated with a statistically significantly increase in the pCR rate (P=0.29). All included covariates exhibited standardized differences below 0.1, indicating a well-balanced distribution among these two subsets after PSM. According to pathologists’ evaluations following neoadjuvant treatment and surgery, MPR was 58.8% (10/17) in the nRCIT group. R0 resection was achieved for 94.1% (16/17) of the patients who underwent surgery. The pCR of primary lesions was 52.9% (9/17). The cases demonstrating pathological responses are presented in Figure 2.

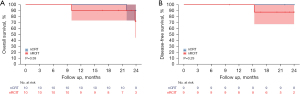

The Survminer package in R language was employed to generate the overall survival (OS) curve, DFS, and OS rates for both groups. The log-rank test was utilized to assess any discrepancies in the survival curves among different groups. The findings revealed that there was no significant disparity between nRCIT and nCRT in terms of DFS or OS. The 1-year OS rate of nRCIT was 88.2%, and the 2-year OS rate was 65.0%, as seen in Figure 3A,3B. At the same time, a multi-factor correction analysis was performed, which was consistent with the PSM results (Tables 2,3). In this study, pCR was improved compared with the standard regimen of nCRT, and the 1- and 2-year DFS, OS of the two groups were similar, suggesting the feasibility of the treatment regimen.

Table 2

| Variables | Estimate | Std. error | Statistic | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||||

| nCRT | 0.000 | Reference | |||

| nRCIT | −0.004 | 0.793 | −0.005 | 0.996 (0.211, 4.712) | >0.99 |

| Age | −0.103 | 0.041 | −2.485 | 0.902 (0.832, 0.979) | 0.01 |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| No | 0.000 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.191 | 0.705 | 1.689 | 3.290 (0.826, 13.105) | 0.09 |

| TNM staging | |||||

| II + IIIA | 0.000 | Reference | |||

| IIIB | 17.860 | 6,652.703 | 0.003 | NA | >0.99 |

| IVA | 20.191 | 6,652.703 | 0.003 | NA | >0.99 |

| Cycles of CT | |||||

| 1–2 | 0.000 | Reference | |||

| 3–6 | 0.449 | 0.539 | 0.833 | 1.566 (0.545, 4.501) | 0.40 |

OS, overall survival; std., standard; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; nRCIT, nCRT combined with immunotherapy; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; CT, chemotherapy; NA, not applicable.

Table 3

| Variables | Estimate | Std. error | Statistic | HR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | |||||

| nCRT | 0.000 | Reference | |||

| nRCIT | −0.161 | 1.139 | −0.141 | 0.851 (0.091, 7.934) | 0.89 |

| Age | −0.027 | 0.053 | −0.519 | 0.973 (0.877, 1.079) | 0.60 |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| No | 0.000 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 1.479 | 1.120 | 1.321 | 4.390 (0.489, 39.417) | 0.19 |

| TNM staging | |||||

| II + IIIA | 0.000 | Reference | |||

| IIIB | 18.099 | 9,365.765 | 0.002 | NA | >0.99 |

| IVA | 0.724 | 25,156.137 | 0.000 | 2.063 (0.000, Inf) | >0.99 |

| Cycles of CT | |||||

| 1–2 | 0.000 | Reference | |||

| 3–6 | 1.106 | 0.811 | 1.365 | 3.024 (0.617, 14.806) | 0.17 |

DFS, disease-free survival; std., standard; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; nRCIT, nCRT combined with immunotherapy; TNM, tumor-node-metastasis; CT, chemotherapy; NA, not applicable; Inf, infinite.

AEs

The most common AEs among the 22 patients in the nRCIT group were lymphocytopenia (100.0%), anemia (95.5%), leukopenia (90.9%), esophagitis (68.2%), decreased platelet count (63.6%), pneumonitis (31.8%), and fatigue (31.8%). Most AEs were grade I or II, except for leukopenia, which was grade III or higher. One patient developed grade 3 radiation pneumonitis. Among 22 patients, 17 who underwent surgery experienced perioperative-related AEs in several grades. Among these 17 patients, 3 (17.6%) had anastomotic leakage and 1 (5.9%) did not survive due to aspiration pneumonia during the perioperative period, as seen in Table 4. This deceased patient underwent IMRT between 22 May 2019 and 24 June 2019. Radiotherapy was administered to the esophageal lesions, mediastinum, double supraclavicular lymphatic drainage areas, and radiotherapy was administered in daily fractions of 1.8 Gy (total cumulative dose of 4,140 Gy). Simultaneously, this patient was treated weekly with paclitaxel combined with carboplatin concurrent chemotherapy for a total of 4 cycles as well as concurrent 2 cycles of immunotherapy including sintilimab 200 mg Q3W. On 12 August 2019, the patient underwent radical esophagectomy, but 3 days after surgery, developed bile reflux and aspiration. A large amount of yellow bile-like fluid was found in the trachea under fiberoptic bronchoscopy. Aspiration pneumonia was diagnosed, and type II respiratory failure occurred. Following that, tracheal intubation was performed, but the anti-infection treatment with third-line antibiotics was not effective. Tracheotomy was performed on the 5th postoperative day, but the patient developed anastomotic leakage and bacteremia thereafter. On the 8th postoperative day, the patient exhibited a sharp increase in C-reactive protein (CRP), accompanied by septic shock, respiratory and circulatory failure, and ultimately death. It is worthwhile to mention that follow-up methods such as telephone calls and checking outpatient medical records were used during the 2-year timeline of the study.

Table 4

| Events | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Events of all grades during neoadjuvant therapy (n=22) | |

| Leukopenia | 20 (90.9) |

| Lymphopenia | 22 (100.0) |

| Anemia | 21 (95.5) |

| Decreased platelet count | 14 (63.6) |

| Pneumonitis | 7 (31.8) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (4.5) |

| Fatigue | 7 (31.8) |

| Esophagitis | 15 (68.2) |

| Events of grade ≥3 during neoadjuvant therapy (n=22) | |

| Leukopenia | 6 (27.3) |

| Lymphopenia | 20 (90.9) |

| Esophagitis | 4 (18.2) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (4.5) |

| Postoperative events (n=17) | |

| Pneumonia | 3 (17.6) |

| Pneumothorax | 3 (17.6) |

| Anastomotic leakage | 3 (17.6) |

| arrhythmias | 1 (5.9) |

| Hoarseness | 2 (11.8) |

| Atelectasis | 2 (11.8) |

AEs, adverse events.

The complications between both groups after PSM are summarized in Table 5. The incidence of anastomotic leakage, pneumonia, arrhythmias, esophagitis, hoarseness, leukopenia, anemia, decreased platelet count, lymphopenia, fatigue, and nausea were comparable in both groups. Therefore, we believe that the addition of immunotherapy does not increase the toxic and side effects of nCRT, so this treatment mode seems safe.

Table 5

| Outcomes | nCRT (n=10) | nRCIT (n=10) | Before PSM | After PSM | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| pCR | 2 (20.0) | 4 (40.0) | 2.67 (0.38, 24.34) | 0.34 | 0.18 (0.01, 5.86) | 0.29 | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 3 (30.0) | 1 (10.0) | 0.26 (0.01, 2.54) | 0.28 | Inf (0, Inf) | >0.99 | |

| Pneumonia | 1 (10.0) | 2 (20.0) | 2.25 (0.18, 54.04) | 0.54 | 0.08 (0, 3.13) | 0.16 | |

| Arrhythmias | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | NA | – | – | |

| Esophagitis | 10 (100.0) | 7 (70.0) | 0 (NA, Inf) | >0.99 | 1 (0, Inf) | 1 | |

| Hoarseness | 0 (0.0) | 1 (10.0) | – | NA | – | – | |

| Leukopenia | 5 (50.0) | 4 (40.0) | 0.67 (0.11, 3.93) | 0.65 | 0.86 (0.03, 24.95) | 0.92 | |

| Anemia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – | – | – | |

| Decreased platelet count | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | NA | – | – | |

| Lymphopenia | 8 (80.0) | 9 (90.0) | 2.25 (0.18, 54.04) | 0.54 | 0 (NA, Inf) | >0.99 | |

| Fatigue | 1 (10.0) | 4 (40.0) | 6 (0.68, 133.97) | 0.15 | 0.3 (0.01, 9.14) | 0.44 | |

| Nausea | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (0.04, 28) | >0.99 | Inf (0, NA) | >0.99 | |

PSM, propensity score matching; nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; nRCIT, nCRT combined with immunotherapy; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; NA, not applicable; Inf, infinite.

Discussion

Immunotherapy is becoming increasingly important for varying cancer treatments (7,11-15). This is evident as recent clinical trials such as KEYNOTE-590, CheckMate 648, ORIENT-15, JUPITER-06, and Astrum-007 have demonstrated that a combination of first-line immunotherapy and chemotherapy significantly enhances advanced EC’s survival outcomes. Rahim et al. presented that PD-1 antibody therapy stimulates exhausted precursor T cells in non-metastatic lymph nodes, but not in metastatic lymph nodes (7). Also, immune-targeting agents exhibit anti-tumor activity prior to lymph node dissection, indicating their potential as a pre-operative treatment option. Consequently, the researchers administered these immune-targeting agents preoperatively to optimize their therapeutic effects.

In the present work, 17 patients underwent esophagectomy following nRCIT, among whom seven achieved pCR, representing a prevalence of 42.10% [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.18–5.86]. In comparison with the control group following PSM, the patients exhibited a slightly elevated but statistically insignificant (42.10% vs. 34.0%, P=0.29) pCR rate, suggesting a potential advantage of nRCIT in enhancing pCR among patients with EC. Another single-arm phase II study on neoadjuvant chemotherapy combined with immunization in ESCC from 2019 to 2022 was conducted in our center (16), and the results showed that pCR was 21.6% (8/37) and R0 removal rate was 89.2% (33/37), which was numerically lower than nRCIT.

It is important to mention that the published PALACE-1 study (8), involving concurrent immunotherapy in conjunction with chemoradiotherapy, achieved an unprecedented pCR rate of 55.6%. It is the highest value documented pCR rate in current clinical research of nRCIT to date. However, in adenocarcinoma, the PERFECT trial (9) demonstrated a pCR rate of 25%, whereas that of the CROSS study was 23% (2). In Chen et al.’s phase II clinical study (NEOCRTEC1901), a 50% response rate was reported, with a 95% CI ranging from 35% to 65% (17). In this study, pCR rates were comparatively higher in the treatment group compared to the control group. However, the difference in pCR rates did not reach statistical significance (50% vs. 36%, P=0.19).

All these studies indicate the safety of the combination of immunotherapy and chemoradiotherapy, which does not exacerbate patients’ toxicity or AEs. The majority of AEs observed in the PALACE-1 study were classified as grade I or II, with lymphocytopenia being the only AE in grade III or higher, accounting for 92% (12/13) of cases (8). The most commonly observed AEs in the NEOCRTEC1901 study among grade III/IV patients were myelosuppression and gastrointestinal reactions, with an incidence ranging from 4% to 9% (17).

The outcomes of our study yielded comparable results. Among the 22 included cases, the occurrence of grade 3/4 lymphocyte decline was observed in 90.9% of patients, whereas grade 3/4 leukocyte decline was found in 27.3% of patients. Unfortunately, one patient died from pneumonia during the perioperative period. Radiation esophagitis was also observed, but all AEs were non-fatal. Perioperative complications encompassed anastomotic fistula (17.6%) and the absence of tracheal fistula was detected in 17 patients who underwent surgical procedures. This information is crucial for researchers employing nRCIT therapy. Meanwhile, the NEOCRTEC1901 (17) study reported a 20% incidence of grade 3/4 AEs, including anastomotic fistula (12%), tracheal fistula (7%), and postoperative death attributable to tracheal fistula (2%). Also, In the NEOCRTEC5010 study, nearly 55% of patients who received nCRT showed grade 3/4 hematotoxicity (4), 48.9% developed grade 3/4 leukopenia, and 45.7% developed grade 3/4 neutropenia. Notably, the evidence derived from our data provides substantial support for the fact that administration of immunotherapy during the neoadjuvant stage did not result in an increased incidence of perioperative pneumonia. Noteworthily, there was a pronounced decline in lymphocyte counts. Further research and analysis will be necessary to ascertain if this phenomenon is related to treatment efficacy. These findings highlight the substantial toxicities associated with this treatment of nRCIT and the pressing need for effective management strategies. Representative articles on nCRT and nRCIT for EC in the past 10 years are summarized in Table 6. Both the CROSS study (3) and the 5010 study (4) are multi-center randomized controlled studies with up to 10 years of follow-up data, and their results are still an important basis for the study of neoadjuvant therapy for EC. In the past 5 years, there have been a number of studies on immunization combined with nCRT conducted within China and internationally, but they have basically comprised small-sample, single-center phase II clinical studies, with pCR rates fluctuating between 30% and 56%, similar to the pCR rate in this study. The incidence of pneumonia above grade 3 was almost zero, which also indicates that the addition of immune drugs has not increased the toxic and side effects of treatment. However, due to the lack of long-term follow-up data, whether nRCIT is truly superior to nCRT remains unknown, we look forward to the results of subsequent phase III clinical studies.

Table 6

| Ref. | Study type | Sample size | Pathological condition | Radiotherapy regime | Chemotherapy regime | Immunotherapy regime | Surgery procedure | Outcome | Toxicity (≥ grade 3 pneumonia) (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total dose (Gy)/total fraction (fx) | Technique | R0 (%) | pCR (%) | Median OS (months) | ||||||||

| (1) | RCTs | 178 | AC, SCC, others | 41.40/23=1.8 | 3D-CRT | Paclitaxel + carboplatin | NA | Transthoracic esophagectomy | 92 | AC: 23; SCC: 49 | 49.4 | 0 |

| (3) | RCTs, phase III | 224 | SCC | 40.0/20=2.0 | 3D-CRT | Vinorelbine + cisplatin | NA | McKeown or Ivor Lewis | 98.4 | 43.2 | 100.1 | 0 |

| (7) | Single-arm | 20 | SCC | 41.4/23=1.8 | IMRT | Carboplatin + paclitaxel | Pembrolizumab | McKeown or Ivor Lewis | 94 | 55.6 | NA | 0 |

| (8) | Single-arm, phase II | 40 | AC | 41.4/23=1.8 | 3D-CRT | Paclitaxel + carboplatin | Atezolizumab | Invasive transthoracic esophagectomy | 100 | 30 | 29.7 | 3 |

| (14) | Single-arm, phase II | 44 | SCC | 44.0/20=2.2 | IMRT | Paclitaxel + carboplatin | Toripalimab | McKeown or Ivor Lewis | 98 | 50 | NA | 0 |

nCRT, neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy; nRCIT, nCRT combined with immunotherapy; EC, esophageal cancer; ref., reference; pCR, pathologic complete response; OS, overall survival; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; AC, adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; 3D-CRT, three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy; NA, not applicable; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy.

More importantly, some patients who did not undergo surgery had a higher survival rate in our research. A total of five patients who did not undergo surgery after neoadjuvant therapy were followed-up for up to 4 years. Among these five patients, 2 (40%) survived for over 4 years without experiencing local recurrence or metastasis. The 2-year OS rate was 100%, whereas the 3-year OS rate was 80%; 1 patient passed away due to liver metastasis. Although the sample size in this investigation is limited, the fact that the majority of patients survived for more than 2 years suggests that nRCIT can yield favorable outcomes in certain patients with EC. In recent years, several studies have demonstrated that patients with EC following nCRT alone can achieve comparable pCR rate and long-term survival rate to patients who undergoing surgery (2,3). In such cases, it is crucial to conduct meticulous follow-up observations and salvage surgery for patients with local recurrence, including gastroscopy, ultrasound gastroscopy, CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, and so on, remain contentious and necessitate further exploration. In summary, the early identification of patients who are responsive to nRCIT and the recognition of pCR is vital and helpful for preserving organ function and enhancing the quality of life for EC patients. Despite the existence of various challenges, ongoing research and investigation of pertinent predictors will ultimately lead to improved treatment outcomes for patients with this condition.

This study has some certain limitations. First, the protracted duration of the study [2019–2021], which was temporarily halted due to the perioperative death of one patient and the outbreak of novel coronavirus pneumonia, resulting in a revision of the radiotherapy target following numerous meetings and discussions. Second, the presence or absence of lymph node metastasis is an important factor in the prognosis of patients with EC. Accurate assessment of lymph nodes in EC is critical to selecting appropriate treatments and predicting disease progression. In 2014, regarding PET/CT, accurate preoperative staging of EC was observed (18); it was reported that PET/CT had prediction sensitivity of 81%, specificity of 88%, and accuracy of 86%. In recent years, research on PET-CT in predicting pCR rates and prognostic factors has been extensively carried out (19,20). Clinicians very much hope that patients can use this non-invasive method to obtain the most accurate results of patients before receiving neoadjuvant treatment. Staging is used to provide a basis for patients to choose the correct treatment plan. At present, PET/CT is used to perform staging. Unfortunately, before 2019, due to cost reasons, PET-CT had not been widely popularized, so there is no complete PET-CT data for the two groups of patients. However, as our research team is the first to carry out nRCIT research on EC in China and overseas, our original data is valuable and can be used as a reference. Third, some patient samples were managed in other hospitals and could not be tested in Zhejiang Cancer Hospital for programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1); we were unable to report data in these circumstances. As mentioned above, a 2-year follow-up with patients and their wellbeing is also considered and included in our work, and this strategy provided further insights and positive outcomes. Considering the outcomes of this investigator-initiated, open-label, single-center, phase II trial study, we are proposing to extend our investigations into phase III randomized controlled trials.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrated the safety and feasibility of nRCIT combined with esophagectomy for locally advanced ESCC. It provided the comparison data and analysis for the long-term survival of patients undergoing nRCIT and nCRT. It is evident from the data and analysis that nRCIT is not suboptimal compared to conventional nCRT for EC treatment and may even exhibit potential advantages, considering their pCR rates of 41.2% and 34.1%, respectively. Additionally, the treatment pattern does not seem to elevate the risk of adverse effects on patients or mortality. For patients who achieve a pCR following neoadjuvant therapy only, the strategy of watch and wait and esophageal preservation may be considered, as verified by point-to-point deep biopsy under endoscopic ultrasound, lymph node pathology, and PET-CT imaging. Furthermore, data analysis indicated that immunotherapy can be beneficial for patients in terms of their organ preservation during treatment. This study provides vital information which can be exploited for future search to identify molecular biomarkers that predict the efficacy of neoadjuvant therapy and to establish the standardized efficacy evaluation methods. This will help identify appropriate patients and enhance treatment outcomes and efficacy.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by grants from

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TREND reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1279/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1279/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1279/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1279/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, China [No. IRB-2023-742(IIT)] and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2024;74:229-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med 2012;366:2074-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eyck BM, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM, et al. Ten-Year Outcome of Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Plus Surgery for Esophageal Cancer: The Randomized Controlled CROSS Trial. J Clin Oncol 2021;39:1995-2004. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu S, Wen J, Yang H, et al. Recurrence patterns after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy compared with surgery alone in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from the multicenter phase III trial NEOCRTEC5010. Eur J Cancer 2020;138:113-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deng L, Liang H, Burnette B, et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest 2014;124:687-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelly RJ, Ajani JA, Kuzdzal J, et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in Resected Esophageal or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1191-203. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rahim MK, Okholm TLH, Jones KB, et al. Dynamic CD8+ T cell responses to cancer immunotherapy in human regional lymph nodes are disrupted in metastatic lymph nodes. Cell 2023;186:1127-43.e18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li C, Zhao S, Zheng Y, et al. Preoperative pembrolizumab combined with chemoradiotherapy for oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (PALACE-1). Eur J Cancer 2021;144:232-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- van den Ende T, de Clercq NC, van Berge Henegouwen MI, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy Combined with Atezolizumab for Resectable Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: A Single-arm Phase II Feasibility Trial (PERFECT). Clin Cancer Res 2021;27:3351-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Y, Bao Y, Yang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemoradiotherapy or chemotherapy in esophageal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Immunol 2023;14:1117448. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kato K, Shah MA, Enzinger P, et al. KEYNOTE-590: Phase III study of first-line chemotherapy with or without pembrolizumab for advanced esophageal cancer. Future Oncol 2019;15:1057-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ajani JA, Kato K, Doki Y, et al. CheckMate 648: A randomized phase 3 study of nivolumab plus ipilimumab or nivolumab combined with fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin in patients with unresectable advanced, recurrent, or metastatic previously untreated esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:TPS193. [Crossref]

- Wang ZX, Cui C, Yao J, et al. Toripalimab plus chemotherapy in treatment-naïve, advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (JUPITER-06): A multi-center phase 3 trial. Cancer Cell 2022;40:277-88.e3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu Z, Wang J, Shu Y, et al. Sintilimab versus placebo in combination with chemotherapy as first line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ORIENT-15): multicentre, randomised, double blind, phase 3 trial. BMJ 2022;377:e068714. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song Y, Zhang B, Xin D, et al. First-line serplulimab or placebo plus chemotherapy in PD-L1-positive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a randomized, double-blind phase 3 trial. Nat Med 2023;29:473-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shen D, Chen R, Wu Q, et al. Safety and short-term outcomes of esophagectomy after neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell cancer: analysis of two phase-II clinical trials. J Gastrointest Oncol 2024;15:841-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen R, Liu Q, Li Q, et al. A phase II clinical trial of toripalimab combined with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (NEOCRTEC1901). EClinicalMedicine 2023;62:102118. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ela Bella AJ, Zhang YR, Fan W, et al. Maximum standardized uptake value on PET/CT in preoperative assessment of lymph node metastasis from thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Chin J Cancer 2014;33:211-7. [PubMed]

- Choi Y, Choi JY, Hong TH, et al. Trimodality therapy for locally advanced esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: the role of volume-based PET/CT in patient management and prognostication. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2022;49:751-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Borggreve AS, Goense L, van Rossum PSN, et al. Preoperative Prediction of Pathologic Response to Neoadjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Patients With Esophageal Cancer Using 18F-FDG PET/CT and DW-MRI: A Prospective Multicenter Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2020;106:998-1009. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(English Language Editor: J. Jones)