Acute esophageal necrosis in the post-operative period: a narrative review of presentation, management, and outcomes

Introduction

Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN) is a rare clinical condition characterized by diffuse, circumferential, black mucosal discoloration of the distal esophagus. Classically the mucosal involvement stops abruptly at the gastroesophageal junction, sparing the gastric mucosa. The condition was first described by Goldenberg in 1990 as acute esophagitis, and then further defined as a distinct syndrome by Gurvits et al. in 2007 (1,2). Since then, AEN has been reported in small case series and individual case reports. The cause is likely multifactorial and can be a sequela of severe conditions including multisystem organ failure, sepsis, gastric volvulus, and trauma. Importantly, the mortality in patients with AEN has been documented to be as high as 32% (3).

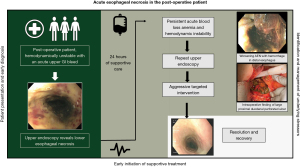

Although rare, the incidence of AEN is likely underestimated, as some patients are misdiagnosed or may succumb to other injuries prior to diagnosis (4). AEN has previously been described in the post-operative period, although the etiology has not been clearly defined (5,6). It is important to further classify both the risk factors and clinical course to help aid in an early identification and successful management of these acutely ill patients. Here we provide a review of the current literature focusing on early identification and management to aid in successful treatment of AEN. In addition, we present an outline of the acute presentation of AEN in the post-operative period, showcasing key initial signs and symptoms, subsequent imaging, and procedures that demonstrate the clinical course of this rare condition (Figure 1). We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1763/rc).

Methods

A literature review of PubMed (MEDLINE) and Google Scholar was conducted 12/1/2020 and an update added from 12/1/2022. Search terms included: acute esophageal necrosis, AEN, and black esophagus (Table 1, Table S1). In combination of clinical experience with AEN, studies included consisted of case-reports, case series and reviews providing information on patient presentation, diagnosis, and management.

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | 12/1/2020 with update in 12/1/2022 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed, Google Scholar |

| Search terms used | Acute esophageal necrosis, AEN, black esophagus |

| Timeframe | 2004–2022 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion: full published papers, English language or with available formal translation Exclusion: non-black esophagus |

| Selection process | Independent selection performed by one individual and selection reviewed with entire group of authors |

| Any additional considerations, if applicable | Rare topic with mostly case reports/series in publication |

Key findings

Epidemiology

Black esophagus, or AEN, was first identified on autopsy in 1967, with a variable incidence reported subsequently (7). Two large retrospective studies reviewed over 100,000 endoscopies to identify cases of AEN and associated conditions. The first study found an overall incidence of 0.01% in 80,000 esophagogastroduodenoscopics (EGDs) over 16 years (8). Half of these patients recovered without recurrence and were alive and well 1 year later, whilst the other half succumbed to their injuries. The second study reviewed 10,295 endoscopies, and documented an incidence of AEN at 0.28% (9). A prospective study evaluating 3,900 endoscopies over a 1-year period found the incidence of AEN (0.2%) to be consistent with prior retrospective studies (10). The incidence is likely underrepresented as some patients may have a self-limited subclinical presentation, and early healing in which they may not present to a hospital for evaluation.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of AEN is multifactorial, linked to the combination of tissue hypoperfusion, as seen in hemodynamic compromise, decreased functional mucosal barrier, and corrosive injury due to gastric fluid (11). Vasculopathies associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and renal disease may be risk factors for tissue injury and low flow states. Hypotension can lead to transient ischemic compromise of the esophagus and may play a role in the development of AEN. In addition, prolonged periods of hypotension intraoperatively may lead to transient ischemia (12). Cases of AEN have been reported in patients with malignancies, anticardiolipin antibody syndrome, and atherosclerosis, possibly due to underlying coagulopathies leading to vascular compromise (13-15).

Vasculopathy of the esophagus may explain the association with duodenal pathology that has been seen in AEN, as the blood supply is shared. Compromised blood flow through the celiac axis may lead to local tissue hypoxia in the duodenum and distal esophagus. This can lead to ulcerations, edema and inflammation of the duodenal bulb, resulting in gastric outlet obstruction, which can further contribute to the development of AEN (16). There also appears to be a link in the extent of esophageal involvement and duodenal disease. Cases of AEN with more extensive proximal and mid-esophageal involvement were associated with significant duodenal disease when compared to more mild cases involving only the distal esophagus (4). Presentation of AEN with disease extension into the mid-esophagus should prompt investigation into duodenal pathology.

Despite the presumed association of low flow states/vasculopathies with AEN, it is important to note the esophagus does have a rich blood supply, from arteries off the aorta, it is difficult to cause outright infarction of the esophagus. However, the lower esophagus is a potential watershed area given its supply off the terminal branches of the left gastric artery, creating a potential watershed area. This may explain the predilection of this area for local injury (17). Some studies hypothesized that esophageal spasm may also pay a role in decreased blood flow to the esophagus, contributing to necrosis (18).

Risk factors

Evaluation of approximately 100 case reports of AEN over the past twenty years has revealed some associated risk factors which may aid in diagnosis (19). Men are at higher risk, as are patients greater than 65 years of age (1,20). There is a clear association of AEN with multiple comorbidities and severe stress such as trauma and multisystem organ failure (21-23). Thirty-eight percent of patients diagnosed with AEN have a documented history of diabetes, 37% have hypertension, and 16% have chronic kidney disease (3). Alcohol abuse, coronary artery disease and hyperglycemia diabetic ketoacidosis are documented risk factors as well (24-34). Malnutrition and baseline anemia are associated with poor outcomes after AEN (35). Gastric volvulus and even paraesophageal hernias have been described in the literature as possible etiologies (36). Duodenal and/or gastric ulcer disease is seen in approximately 4% of patients, and gastroesophageal reflux in 9% (3).

While development of AEN has a strong association with multiple comorbidities, it can occur in otherwise healthy patients. Notably, we have observed this phenomenon in a healthy patient after successful resection of pulmonary neoplasm with minimal co-morbidities who presented with acute onset upper gastrointestinal bleeding (37). In these patients, it is important to look for early presenting signs and symptoms to help guide the diagnosis. Common presenting symptoms include tachycardia or hypotension, in addition to acute onset of epigastric pain and dysphagia.

Based on case reports of AEN in the post-operative period, surgery has been described as a possible trigger. This may be explained by impaired regeneration of the esophagus in response to altered cytokine environment, leading to increased susceptibility to mucosal ischemia. This, in combination with hypotension or blood loss in the peri- and intra-operative period, may explain the increased risk of tissue necrosis in this patient population (38). AEN has been reported after planned operations such as cholecystectomy and rectosigmoid resections in patients with multiple underlying comorbidities (39,40). In these cases, the patients presented with acute onset of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, were identified early, and recovered with limited long-term sequelae. Esophageal necrosis has also been reported in complex amputations associated with systemic infection (41). In that case, the patient developed multisystem organ failure and succumbed to his injuries.

Transplant patients are also at increased risk for AEN, with cases occurring in the immediate post-transplant period and other later presentations attributed to graft vs. host disease (42-46). In some cases, AEN is a consequence of opportunistic infections such as cytomegalovirus esophagitis (47). In these patients, EGD with biopsy is diagnostic, and antivirals are therapeutic (48). Thus, transplant patients represent another population that requires a higher level of suspicion, based on their altered hemodynamics and immunosuppression.

AEN is also reported during the post-operative period after oncologic lung resections (49). This is believed to be associated with the paraesophageal lymph node dissection performed during lung cancer operations (50). As previously discussed, the likelihood of devascularizing the esophagus is low; nevertheless, it is possible to cause transient changes in the microcirculation. This, in combination with potential comorbidities, perioperative changes in hemodynamics, may put these patients at higher risk. It is important to keep AEN in the differential if complications arise in the post-operative period in these patients.

Presentation and diagnosis

Black esophagus classically presents with acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients. This primarily manifests as acute onset of hematemesis but may be more insidious with melena (51). Patients also may have abdominal pain, nausea, reflux, or syncope. Initial patient evaluation would then reveal signs of hemodynamic instability such as tachycardia and hypotension. Laboratory evaluation would show new onset anemia, secondary to acute blood loss, and possibility a reactive leukocytosis.

Endoscopic evaluation remains the gold standard in the diagnosis of AEN. The classic appearance of circumferential necrotic mucosa, affecting mostly the distal esophagus and stopping abruptly at the gastroesophageal junction, is diagnostic; proximal extension can be seen, although diffuse involvement is rare. Other associated endoscopic anomalies include signs of bleeding, duodenal ulcers, gastritis, and edema. Histologic evaluation is not necessary to make the diagnosis but may provide some benefit (52). Findings include necrotic mucosal debris, leukocyte infiltration, vascular thrombi, and other inflammatory changes. Biopsies should be sent for bacterial, viral, and fungal cultures to help narrow the differential, especially in immunocompromised patients as they are at higher risk for infections (11,53).

Staging criteria introduced in 2007 by Gurvits et al. classifies the disease progression and helps guide clinical management (1). Stage 0 is a viable and pre-necrotic esophagus. Stage 1 is the acute phase of AEN, classified by circumferential necrotic and friable mucosa with yellow exudates. As described above, these findings start at the gastroesophageal junction and extend proximally at varying lengths. Stage 2 is the healing phase, characterized by white exudates, pink mucosa, and occasional black patchy areas. The time interval from stage 1 to 2 varies from as early as 1–2 weeks after diagnosis to a month. The final phase, stage 3, is return to normal esophageal mucosa. The time required to recover varies from weeks to a month. Progression from stage 1 to stage 2 can be achieved in as early as 7 days from diagnosis and reached stage 3 in 15 days from correction of the underlying problem (Figure 2).

Initial management

Appropriate management for patients presenting with AEN is supportive care with a focus on the driving cause of their physiologic stressor. Correction of anemia, electrolyte abnormalities, and strict nil-per-os should be implemented immediately. Medical management with intravenous proton pump inhibitors is also necessary to mitigate local damage to the gastric mucosa. The focus should then shift to the identification and management of any underlying problems. Endoscopy should be performed early and repeated to classify progression. While prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended, they should be utilized in patients with fevers or rapid decompensation where esophageal perforation is suspected. Computed tomography (CT) angiogram has not been described as necessary for diagnosis; however, it may help eliminate other differential causes of ischemia (Figure 3). Close hemodynamic monitoring in an intensive care unit setting is recommended, as this condition can quickly progress to requiring emergent and aggressive intervention.

Parenteral nutrition should be initiated once the patient has stabilized, as nutrition is importation for mucosal recovery. Surgically placed feeding tubes are not recommended in all patients, however, there are situations where they provide benefit. If the patient is not suited for oral nutrition for an extended period, a feeding tube can be a useful adjunct in optimizing nutritional status during the post-operative course. Oral nutrition can be attempted after recovery from the acute phases. If it is not tolerated, parental nutrition should be continued until the esophagus has fully recovered (54).

Sequela

Acute surgical intervention in cases of AEN is reserved for extreme cases. Esophageal perforation is seen in approximately 7% of all known cases, and is the most worrisome complication with a documented mortality rate of 40% (1,55). The AEN staging system helps guide complication potential during each phase of the disease. Perforation usually occurs during stage 1 and stricturing in stages 2 and 3 (1). In general, strictures can be managed with endoscopic dilation (56,57). Additionally, fully covered metallic stenting of the esophagus has been successfully performed to aid in controlling bleeding although embolization was also performed (58). Perforation is rare, but cases of successful surgical intervention have been reported. Akaishi et al. reported a case of perforation on day 7 after diagnosis, requiring emergent subtotal esophagectomy with esophagostomy and enterotomy (59). The patient recovered well, but did subsequently develop strictures, requiring multiple dilations and eventual reconstruction (59). Additional cases of severe strictures have been reported that eventually required esophagectomy when dilation could not safely be performed (60).

As discussed above, there has been an observed association with duodenal ulcers and inflammation with AEN (61). Recurrent AEN has been documented in patients with duodenal pathology, likely secondary to persistent inflammation and gastric outlet obstruction (35). This is important to keep in mind as a possible underlying cause in patients presenting with AEN, as their worsening clinical status may be related to progression of ulcerative disease (i.e., perforation). Initial endoscopic evaluation of patients presenting with AEN should include an examination of the duodenum for potential pathology. Although rare, AEN should be in the differential diagnoses in post-operative patients with acute onset of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, especially if they have a history of ulcerative disease.

Conclusions

AEN is a rare condition in which the mucosa of the distal esophagus becomes necrotic, usually as a response to a severe physiologic stress. Surgery is widely recognized as a physiologic stressor and as a result AEN can be seen in the post-operative period. While the reports are limited in this population, the management of AEN remains the same as in non-surgical stimuli. Identifying risk factors and trends may help diagnose this condition early, lower long-term morbidities. While AEN has been documented as having a high mortality rate, it is possible with early identification and intervention that patients can recover without long-term sequelae.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1763/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1763/prf

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-22-1763/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gurvits GE, Shapsis A, Lau N, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis: a rare syndrome. J Gastroenterol 2007;42:29-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldenberg SP, Wain SL, Marignani P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis. Gastroenterology 1990;98:493-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Abdullah HM, Ullah W, Abdallah M, et al. Clinical presentations, management, and outcomes of acute esophageal necrosis: a systemic review. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;13:507-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gurvits GE, Cherian K, Shami MN, et al. Black esophagus: new insights and multicenter international experience in 2014. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60:444-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chawla GS, Kukova L, Behin DS. Unusual case of acute oesophageal necrosis. BMJ Case Rep 2022;15:e248084. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shah J, Savlania A, Bush N, et al. Three cases of an unusual cause of haematemesis: black oesophagus. Trop Doct 2020;50:152-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brennan JL. Case of extensive necrosis of the oesophageal mucosa following hypothermia. J Clin Pathol 1967;20:581-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moretó M, Ojembarrena E, Zaballa M, et al. Idiopathic acute esophageal necrosis: not necessarily a terminal event. Endoscopy 1993;25:534-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Augusto F, Fernandes V, Cremers MI, et al. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: a large retrospective case series. Endoscopy 2004;36:411-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ben Soussan E, Savoye G, Hochain P, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis: a 1-year prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;56:213-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:3219-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schizas D, Theochari NA, Mylonas KS, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis: A systematic review and pooled analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2020;12:104-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Odelowo OO, Hassan M, Nidiry JJ, et al. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: a case report. J Natl Med Assoc 2002;94:735-7.

- Yasuda H, Yamada M, Endo Y, et al. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: role of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Gastroenterol 2006;41:193-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burtally A, Gregoire P. Acute esophageal necrosis and low-flow state. Can J Gastroenterol 2007;21:245-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marie-Christine BI, Pascal B, Jean-Pierre P. Acute necrotizing esophagitis: another case. Gastroenterology 1991;101:281-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papakonstantinou NA, Patris V, Antonopoulos CN, et al. Oesophageal necrosis after thoracic endovascular aortic repair: a minimally invasive endovascular approach-a dramatic complication. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2019;28:9-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rakovich G, Rolland S. Necrotizing Esophagitis: A Big Squeeze? J Can Assoc Gastroenterol 2022;5:103-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rehman O, Jaferi U, Padda I, et al. Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Manifestations of Acute Esophageal Necrosis in Adults. Cureus 2021;13:e16618. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vohra I, Desai P, Thapa Chhetri K, et al. Acute Esophageal Necrosis: A Case Series From a Safety Net Hospital. Cureus 2020;12:e8542. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lacy BE, Toor A, Bensen SP, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc 1999;49:527-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thomas M, Sostre Santiago V, Suhail FK, et al. The Black Esophagus. Cureus 2021;13:e18655. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polavarapu A, Gurala D, Mudduluru B, et al. A Case of Acute Esophageal Necrosis from Unruptured Thoracic Aortic Aneurysm. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2020;2020:3575478. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rigolon R, Fossà I, Rodella L, et al. Black esophagus syndrome associated with diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Clin Cases 2016;4:56-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim YH, Choi SY. Black esophagus with concomitant candidiasis developed after diabetic ketoacidosis. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13:5662-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitawaki D, Nishida A, Sakai K, et al. Gurvits syndrome: a case of acute esophageal necrosis associated with diabetic ketoacidosis. BMC Gastroenterol 2022;22:277. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Melo Valadão I, Couto L, Benites MG. Gurvits syndrome in diabetic ketoacidosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2022;114:302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trad G, Sheikhan N, Ma J, et al. Acute Esophageal Necrosis Syndrome (Black Esophagus): A Case Report of Rare Presentation. Cureus 2022;14:e24276. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Avramidou D, Violatzi P, Zikoudi DG, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis complicating diabetic ketoacidosis in a patient with type II diabetes mellitus and excessive cola consumption: a case report. Diabetol Int 2022;13:315-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Moss K, Mahmood T, Spaziani R. Acute esophageal necrosis as a complication of diabetic ketoacidosis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021;9:9571-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deliwala SS, Lakshman H, Congdon DD, et al. Black Esophagus in the Setting of Alcohol Abuse after External Beam Radiation. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2020;14:443-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Siddiqi A, Chaudhary FS, Naqvi HA, et al. Black esophagus: a syndrome of acute esophageal necrosis associated with active alcohol drinking. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2020;7:e000466. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuridullah R, Patel V, Melki G, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis masquerading acute coronary syndrome. Autops Case Rep 2020;10:e2019136. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Coles M, Madray V, Uy P. Acute Esophageal Necrosis in a Septic Patient with a History of Cardiovascular Disease. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2020;2020:1416743. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SM, Song KH, Kang SH, et al. Evaluation of prognostic factor and nature of acute esophageal necrosis: Restropective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e17511. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li CJ, Claxton BB, Block P, et al. Acute Esophageal Necrosis Secondary to a Paraesophageal Hernia. Case Rep Gastroenterol 2021;15:594-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya S, Blau JE, Koh C. Acute oesophageal necrosis in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: an undescribed complication. BMJ Case Rep 2021;14:e238214. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dias E, Santos-Antunes J, Macedo G. Diagnosis and management of acute esophageal necrosis. Ann Gastroenterol 2019;32:529-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Loghmari MH, Ben Mansour W, Guediche A, et al. Black esophagus: a case report. Tunis Med 2018;96:142-7.

- Rodrigues BD, Dos Santos R, da Luz MM, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis. Clin J Gastroenterol 2016;9:341-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shafa S, Sharma N, Keshishian J, et al. The Black Esophagus: A Rare But Deadly Disease. ACG Case Rep J 2016;3:88-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu MA, Mulki R, Massaad J. The Black Esophagus in the Renal Transplant Patient. Case Rep Nephrol 2019;2019:5085670. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Caravaca-Fontán F, Jimenez S, Fernández-Rodríguez A, et al. Black esophagus in the early kidney post-transplant period. Clin Kidney J 2014;7:613-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mealiea D, Greenhouse D, Velez M, et al. Acute Esophageal Necrosis in an Immunosuppressed Kidney Transplant Recipient: A Case Report. Transplant Proc 2018;50:3968-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Makeen A, Al-Husayni F, Banamah T. Acute Esophageal Necrosis Early after Renal Transplantation. Case Rep Nephrol 2021;2021:5164373. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim NY, Lee YJ, Cho KB, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis after kidney transplantation: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e24623. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Trappe R, Pohl H, Forberger A, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis (black esophagus) in the renal transplant recipient: manifestation of primary cytomegalovirus infection. Transpl Infect Dis 2007;9:42-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mena Lora A, Khine J, Khosrodad N, et al. Unusual Manifestations of Acute Cytomegalovirus Infection in Solid Organ Transplant Hosts: A Report of Two Cases. Case Rep Transplant 2017;2017:4916973. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugiura Y, Gochou S, Sakurai Y, et al. Acute Necrotizing Esophagitis Occurred after Lung Resection for Lung Cancer. Kyobu Geka 2020;73:121-3.

- Katsuhara K, Takano S, Yamamoto Y, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis after lung cancer surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;57:437-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Melki G, Nanavati S, Kumar V, et al. A case of unusual presentation of acute esophageal necrosis with pneumonia. Int J Health Sci (Qassim) 2020;14:66-8.

- Colón AR, Kamboj AK, Hagen CE, et al. Acute Esophageal Necrosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study Highlighting the Mayo Clinic Experience. Mayo Clin Proc 2022;97:1849-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tsokos M, Herbst H. Black oesophagus: a rare disorder with potentially fatal outcome. A forensic pathological approach based on five autopsy cases. Int J Legal Med 2005;119:146-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brar TS, Helton R, Zaidi Z. Total Parenteral Nutrition Successfully Treating Black Esophagus Secondary to Hypovolemic Shock. Case Rep Gastrointest Med 2017;2017:4396870. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harner A, Mitchell A, Kilbourne M. Acute Esophageal Necrosis Resulting in Esophageal Perforation. Am Surg 2019;85:e339-41.

- Jinushi R, Ishii N, Yano T, et al. Endoscopic balloon dilation for the prevention of severe strictures caused by acute esophageal necrosis. DEN Open 2022;2:e43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sandhu S, Wang T, Prajapati D. Acute esophageal necrosis complicated by refractory stricture formation. JGH Open 2021;5:528-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Al Bayati I, Badhiwala V, Al Obaidi S, et al. Endoscopic Treatment of Black Esophagus With Fully Covered Metallic Stent. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep 2022;10:23247096221084540. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akaishi R, Taniyama Y, Sakurai T, et al. Acute esophageal necrosis with esophagus perforation treated by thoracoscopic subtotal esophagectomy and reconstructive surgery on a secondary esophageal stricture: a case report. Surg Case Rep 2019;5:73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Imaoka K, Harano M, Oshita K, et al. Indocyanine green fluorescence imaging for subtotal esophagectomy due to esophageal stenosis after acute esophageal necrosis: a report of two cases. Clin J Gastroenterol 2021;14:415-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sánchez Cánovas M, López Martín A. Severe gastrointestinal toxicity secondary to fluoropyrimidines: acute esophageal necrosis associated extensive duodenal mucositis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2020; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref]