|

Original Article

Results of chest wall resection and reconstruction in 162 patients with benign and malignant chest wall disease

Manoucheher Aghajanzadeh1, Ali Alavy1, Mehrdad Taskindost2, Zahra Pourrasouly2, Gilda Aghajanzadeh2, Sara massahnia3

1Department of thoracic surgery & Pulmonology, Respiratory Diseases & TB Research Center of Guilan University of Medical Science (GUMS), Razi Hospital, Rasht, Iran; 2Department of general surgery, Respiratory Diseases & TB Research Center of Guilan University of Medical Science (GUMS), Razi Hospital, Rasht, Iran; 3Respiratory Diseases & TB Research Center of Guilan University of Medical Science (GUMS), Razi Hospital, Rasht, Iran

Corresponding to: Manoucheher Aghajanzadeh, MD, Department of thoracic surgery, Respiratory Diseases & TB Research Center of Guilan University of Medical Science (GUMS), Razi Hospital, Rasht 999067, sardar gangle ave, Iran. Tel: +98-1315550028; Fax: +98-1315530169. Email: maghajanzadeh2003@yahoo.com.

|

|

Abstract

Background: Chest wall resection is a complicated treatment modality with significant morbidity. The purpose of

this study is to report our experience with chest wall resections and reconstructions.

Methods: The records of all patients undergoing chest wall resection and reconstruction were reviewed. Diagnostic

procedures, surgical indications, the location and size of the chest wall defect, performance of lung resection, the

type of prosthesis, and postoperative complications were recorded.

Results: From 1997 to 2008, 162 patients underwent chest wall resection.113 (70%) of patients were male. Age of

patients was 14 to 69 years. The most common indications for surgery were primary chest wall tumors. The most

common localized chest wall mass has been seen in the anterior chest wall. Sternal resection was required in 22

patients, Lung resection in 15 patients, Rigid prosthetic reconstruction has been used in 20 patients and nonrigid prolene

mesh and Marlex mesh in 40 patients. Mean intensive care unit stay was 8 days. In-hospital mortality was 3.7

% (six patients).

Conclusion: Chest wall resection and reconstruction with Bone cement sandwich with mesh can be performed as a

safe and effective surgical procedure for major chest wall defects and respiratory failure is lower in prosthetic reconstruction

patients than previously reported ( 6).

Key words

chest wall tumor; chest wall resection; chest wall disease

J Thorac Dis 2010;2:81-85. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.02.02.005

|

|

Introduction

Early attempts for chest wall resection were limited

by availability of suitable materials for reconstruction.

Initial materials used for chest reconstruction included

autogenous tissue such as fascia lata grafts, rib grafts, or

large cutaneous grafts ( 1, 2). Since the first known chest

wall resection in the18th century, improvements in surgical

technique and anesthesia, critical care units, antibiotics,

and the development and refinements in reconstraction

techniques have allowed extensive chest wall resection

to be performed with acceptable morbidity and mortality

( 3). After radical en bloc chest wall resection, skeletal reconstraction when appropriate and adequate skin

coverage to preserve the reconstraction are the essential

elements for successful management of the chest wall

defects. In cases of chest wall tumors wide excision and

reconstraction is very important because distant metastasis

and local recurrence in incomplete resection is high

leading to poor survival. Since 1980s, the use of prosthetic

materials including polytetrafluoroethylene, polypropylene

mesh, and polypropylene mesh–methylmethacrylate

composites combined with the use of myocutaneous flaps

has enabled successful reconstruction of even the largest

chest wall defects ( 3). Although primary closure of muscle

and skin after chest wall resection is attainable in most

cases, many patients commonly require more sophisticated

reconstructive soft-tissue and skin coverage. A variety

of techniques including pedicled muscle transposition,

free muscle flaps, and omental flaps have been used to

provide adequate wound coverage, it allows quick healing,

early rehabilitation, and better cosmesis ( 4). Respiratory

complications continue to be the most frequent and are

reported in 20% to 24% of the patients ( 3). The Purpose of

this study is to retrospectively review our experience with chest wall resections and reconstruction and determine the

postoperative complications

|

|

Patients and methods

It is a retrospective study performed on the available

charts of 162 consecutive patients who underwent chest

wall resection and reconstruction at Guilan University of

Medical Sience Razi Hospital between1997 and 2008. All

patients with more than two rib resections were included

in the present series. Mean age was 40 years (range 20 to

70); 114 (70%) were men and 48 (30%) women. Prior to

chest wall resections, all patients underwent pulmonary

function tests. All patients received conventional chest

roentgenography, which occasionally detects a defect or

mass. For patients with a mass, a computed tomography

(CT) scan or MRI of the chest was done to evaluate the

extentension of the lesion and a tissue diagnosis

utilizing

fine or core needle aspiration or incisional biopsy was

attempted. In patients with suspected distant metastases,

CAT Scans were used. Patients’ charts were retrospectively

reviewed for age, sex, anatomic defect during the surgical

resection, the number of ribs or the portion of sternum

resected, and the surgical reconstruction technique. The

in-hospital outcomes as morbidity and mortality, length of

hospital stay (in the intensive care unit, and postoperative,

hospital stay) was reviewed. For the infected chest wall

requiring resection Vicry mesh was used in addition to

muscle flap coverage. In Some instances where chest wall

resection was done for radionecrosis only muscle flaps

were used.

|

|

Results

During 11 years duration, 162 patients underwent chest

wall resection .113 (70%) of patients were male. Age of

patients was 14 to 69 years. (Median age of patients was

40 years). The most common indications for surgery were

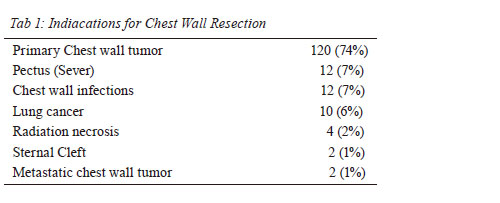

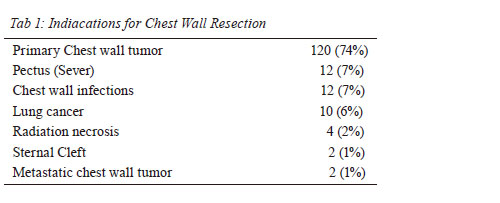

primary chest wall tumors (120patients, 74%) ( Table 1).

Ten patients (6%) underwent concomitant lung surgery and

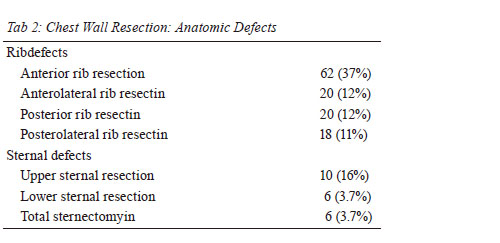

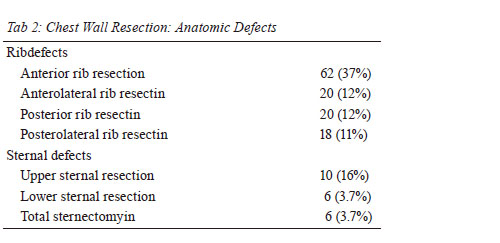

chest wall resection. The median number of ribs resected

was 3 (range, 2 to 6). The anterior and lateral ribs were the

most commonly resected ribs (62 patients,

37%; A total of

22 patients underwent sternal resection; the most common

was an Upper sternal resection in 10 patients. Six patients

(3.7%) required total sternectomy for chondrosarcoma

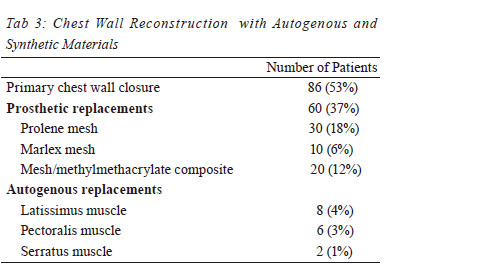

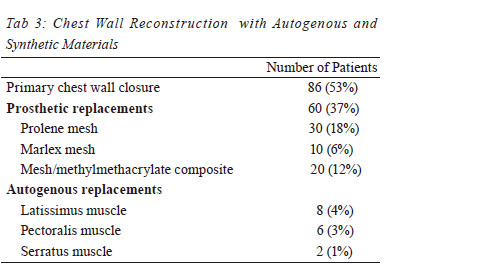

( Table 2). Immediate closure and repair was performed

in all of the patients. Primary repair of the soft tissue and

skin was performed in 86 patients (53%) and synthetic

materials were used for chest wall integrity reconstruction

in 76 patients (Prolene mesh, Marlex mesh, Bone cement

sandwich with mesh). Sixtheen patients (8%) underwent pedicled muscle flap transposition. The three most common

muscle groups utilized were latissimus flap, pectoralis flap

and Latismos dorsi ( Table 3). Bone and soft tissue sarcoma

was the most commonly foung histological chest was

tumor. The overall length of stay in the intensive care unit

in rigid reconstraction patients was 5 to 16 days (median 8

days) and for non-rigid patients was 3 to 8 (median 5 days)

and the postoperative in hospital length of stay in rigid

reconstraction patients was 16 days (range 6 to 42). And for

non-rigid patients was 6 to 10 (median 7 days). Six of 162 patients (3.7%) died during their hospital stay

due to multiplesystem organ failure, including 2 of the 18

patients who underwent rigid prosthetic reconstruction

and 4 of the patients undergoing concomitant lung surgery

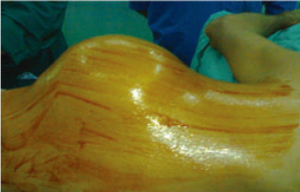

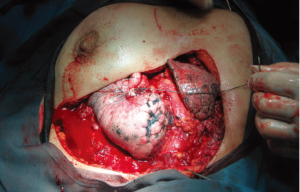

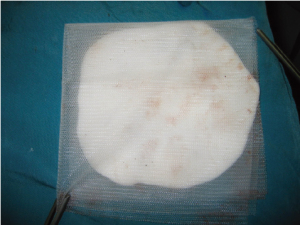

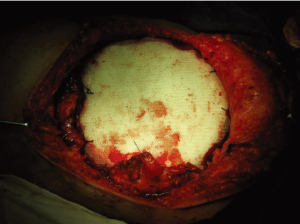

and chest wall resection. We have shown a successful

repair of a patient with lung cancer and chest wall invasion

requiring en bloc removal of the entire forequarter, the

third to eight ribs, and the involved chest wall. The defect was repaired with a double fold of prolen mesh and Bone

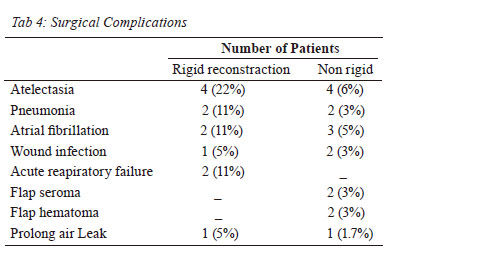

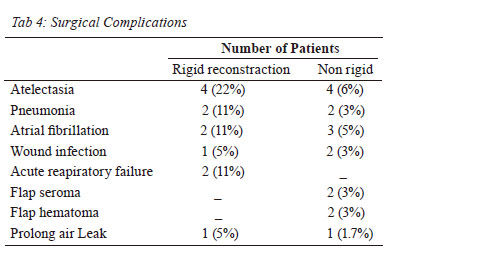

cement sandwich (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4). Twenty-Eight of 76

patients (36 %) had complications during their hospital

stay ( Table 4). The most common complications were

atelectasis (8 patients, 10%), Atrial fibrillation (5 patients,

6 %) and Pneumonia (4 patients, 5 %). Factors associated with postoperative complications were type of prosthesis,

the location of the lesion, the need for sternal resection,

medical comorbidities, and lung resection and size of the

chest wall defect.

|

|

Discussion

In the treatment of patients requiring chest wall

resection, three tenets of surgical resection should be

main Tained ( 5). First, a sufficient amount of tissue must

be resected to dispose of all devitalized tissue. Second,

in segments of large chest wall resections a replacement

must be found to restore the rigid chest wall to prevent

physiologic flail. Third, healthy soft – tissue coverage is

essential to seal the pleural space, to protect the viscera

and great vessels, and to prevent infection. Although there

is controversy as to which chest wall lesions should be

reconstructed but, generally, lesions less than 5 cm in size

in any location, and those up to 10 cm in size posteriorly do not need reconstruction for functional reasons ( 3). Posterior

defects in proximity to the tip of the scapula, larger lesions

likely to produce paradoxical chest wall motion and most

anterior defects require reconstruction ( 6). A basic tenet prior to the initiation of chest wall

reconstruction is an appropriate and thorough chest wall

resection that leaves healthy, viable margins to which

materials and tissues used in a reconstruction may be

anchored securely ( 4). For patients in whom combined pulmonary and chest

wall resection may be required we agree with Pairolero,

that if the mediastinal lymph nodes are not positive, an

en bloc resection is warranted as the 5-year mortality is

more associated with the extent of the pulmonary cancer

than with the extent of chest wall resection ( 7). In contrast

Magdeleinat and colleagues do not consider N2 disease

a contraindication to en bloc resection and have recently

reported an actuarial 5-year survival after complete en

bloc resection of lung cancer invading the chest wall

( 8). Chape and colleagues found that only histologic

differentiation (well versus poorly differentiated) and the

depth of chest wall invasion (parietal pleura versus other)

were independent predictors of long-term survival in

multivariate analyses ( 9). Persisting or recurring chest wall involvement with

breast carcinoma after local excision and radiation therapy

may require chest wall resection to achieve local control

( 10, 11). Chest wall recurrences were found in 1% to 2% of

stage I and in 10% to 12% of stage II breast carcinomas

surgically treated with an extremely variable disease-free

interval ( 11). In current series we have 4 cases of nonhealing

radiation-induced ulcers who underwent chest wall

resection and reconstruction. With modern surgical technique a wide range of

reconstructive options are at the surgeon's disposal and

hence it is imperative that the appropriate procedure be

selected in a given patient. For small defects (less than 5

cm) or those located posteriorly under the scapula above the

fourth rib (after resection of Pancoast tumors) the skeletal

component can be ignored and the defect is uausally closed

with only soft tissue. For patients undergoing large chest

wall defects or pulmonary collapse, stabilization of the

chest wall defect may be indicated. LeRoux and Shama

have set forth the ideal characteristics of a prosthetic

material ( 12): A. rigidity to abolish paradoxical chest

motion, B. inertness allow in-growth of fibrous tissue and

decrease the likelihood of infection, c. malleability so that

it can be fashioned to the appropriate shape at the time of

operation, D. radiolucency to allow radiographic follow-up

of the underlying problem ( Fig. 5). Historically, bone, cartilage, metal sheets, superstructures

with autogenous rib graft, fascia lata, Teflon, and numerous other substances were used with minimal

success ( 13). In cases where structural integrity is necessary for

preventing chest wall collapse, methyl methacrylate

sandwich, silicone, Tef lon, or acrylic materials have

been utilized ( 5). The use of a rigid prosthesis using a

PPM-methylmethacrylate “sandwich” was developed by

some of the authors and has since been widely adopted

( 1, 3, 14, 15). It is our practice to use this rigid prosthesis for

those defects likely to produce a flail segment, including

large anterior or lateral lesions, or the area of the sternum

in which some protection of the underlying organs is

essential. This technique provides rigid repair that can

be tailored to any size, shape, or contour of chest wall

defect. The present report represents a good experience

with the use of this method of reconstruction. While the

importance of rigidity in chest wall reconstruction is

still unclear, observations of chest wall trauma provide

the significance of paradoxic motion of the chest wall.

However, this respiratory uncoordinated motion is seen

in almost every major resection of the chest wall but it

is not associated with pulmonary insufficiency, which is

seen with its traumatic counterpart, flail chest. We have

commonly used Bone cement sandwich with prolene mesh

with excellent physiologic and aesthetic success. Reports

of transposition of the latissimus dorsi muscle for chest

wall coverage had been described in 1896 by Tansini

( 18). The numerous advances in chest reconstruction over

the years with the introduction of muscle and musculocutaneous

flaps have made them the mainstay in chest wall

reconstruction ( 19). The thoracic trunk is well suited for

vascularized coverage given the many local muscle flaps

(eg, latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major, rectus abdominis,

trapezius, or deltoid muscles) or greater omentum (used

alone or in combination as potions for wound coverage) ( 20). Respiratory complications including pneumonia, acute

respiratory distress syndrome, and atelectasis are by far the

most common and have been reported to be as high as 24%

( 4). Wound complications such as infection, dehiscence,

flap loss, and hematoma are reported to occur in 8% to

20% ( 3, 4, 14). Our experience demonstrates that respiratory

complications occur red in 18% of 76 patients and

included pneumonia, atelectasis, respiratory failure (adult

respiratory distress syndrome) and Prolong air leak. Tthis

frequency of complications is far less than in other series

( 3, 4). Our experience reiterates the fact that respiratory

complications will remain a significant problem. Lardinois

and coworkers recently reported their experience with 26

patients having chestwall resection and reconstruction with

mesh/methylmethacrylate (MMM). The authors report

that there was no 30-day mortality and nearly all patients

had a satisfactory cosmetic and functional outcome. ( 15).

The prostheses were imaged with cine-magnetic resonance

imaging and found to exhibit no paradoxic chest wall

motion in any patient ( 15). In our series factors associated

with postoperative complications and mortality were

sternal resection, concominant lung resction and patient

pulmonary capability, size of the chest wall resection as

others ( 15). In conclusion: The key to a successful outcome

in these complex cases is the coordinated effort by the

surgical teams. The frequency of respiratory complications

can be decreased by routine use of a rigid prosthesis for

reconstruction.

|

|

References

- Carbone M, Pastorino U. Surgical treatment of chest wall tumors.

World J Surg 2001;25:218-30.[LinkOut]

- Arnold PG, Pairolero PC. Chest wall reconstructionan account of

500 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg 1996;98:804-8.[LinkOut]

- Deschamps C, Tirnaksiz BM, Darbandi R. Early and long-term

results of prosthetic chest wall reconstruction. J Thorac Cardiovasc

Surg 1999;117:588-92.[LinkOut]

- Mansour KA, Thourani VH, Losken A, Reeves JG, Miller JI Jr,

Carlson GW, et al. Chest wall resections and reconstruction: a

25-year experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;73:1720-5;discussion

1725-6.[LinkOut]

- Graeber GM, Langenfeld J. Chest wall resection and reconstruction. In: Franco KL, Putman JR, editors. Advanced therapy in thoracic

surgery. London: BC Decker;1998.p.175-85.

- Weyant MJ, Bains MS, Venkatraman E, Downey RJ, Park BJ, Flores

RM, et al. Results of Chest Wall Resection and Reconstruction With

and Without Rigid Prosthesis. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:279-285.[LinkOut]

- Pairolero PC. Extend resections for lung cancer. How far is too far?

Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999;16:S48-50.[LinkOut]

- Magdeleinat P, Alifano M, Benbrahem C. Surgical treatment of lung

cancer invading the chest wall: results and prognostic factors. Ann

Thorac Surg 2001;71:1094-9.[LinkOut]

- Chapelier A, Fadel E, Macchiarini P. Factors affecting long-term

survival after en-bloc resection of lung cancer invading the chest

wall. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2000;18:513-8.[LinkOut]

- Anderson BO, Burt ME. Chest wall neoplasms and their

management. Ann Thorac Surg 1994;58:1774-81.[LinkOut]

- Picciocchi A, Granone P, Cardillo G, Margaritora S, Benzoni

C, D'ugo D. Prosthetic reconstruction of the chest wall. Int Surg

1993;78:221-4.[LinkOut]

- LeRoux BT, Shama DM. Resection of tumors of the chest wall. Curr

Probl Surg 1983;20:345-86.[LinkOut]

- McCormack -PM. Use of prosthetic materials in chest-wall

reconstruction. Surg Clin North Am 1989;69:965-76.[LinkOut]

- McKenna Jr RJ, Mountain CF, McMurtrey MJ, Larson D, Stiles

QR. Current techniques for chest wall reconstructionexpanded

possibilities for treatment. Ann Thorac Surg 1988;46:508-12.[LinkOut]

- Lardinois D, Müller M, Furrer M, Banic A , Gugger M,

Krueger T, et al. Functional assessment of chest wall integrity

after methylmethacrylate reconstr uction. Ann Thorac Surg

2000;69:919-23.[LinkOut]

- McCormack P, Bains M, Martini N, Burt M, Kaiser LR. Methods

of skeletal reconstruction following resection of lung carcinomas

invading the chest wall. Surg Clin North Am 1987;67:979-86.[LinkOut]

- Tansini I. Nuovo processo per amputations della mammella per

cancro. Reform Med 1896;12:3-5.[LinkOut]

- Brown R, Fleming W, Jurkiewicz M. An island flap of the pectoralis

major muscle. Br J Plast Surg 1977;30:161-5.[LinkOut]

- Cohen M, Ramasastry SS. Reconstruction of complex chest wall

defects. Am J Surg 1996;172:35-40.[LinkOut]

- Hultman CS, Culbertson JH, Jones GE, Losken A, Kumar AV,

Carlson GW, et al. Thoracic reconstruction with the omentum:

indications, complica-tions, and results. Ann Plast Surg

2001;46:242-9.[LinkOut]

Cite this article as: Aghajanzadeh M, Alavy A, Taskindost M, Pourrasouly Z, Aghajanzadeh G, massahnia S. Results of chest wall resection and reconstruction in 162 patients with benign and malignant chest wall disease. J Thorac Dis 2010;2(2):81-85. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2010.02.02.005

|