Association of sarcopenia with basic activities of daily living and dyspnea-related limitations in patients with interstitial lung disease

Highlight box

Key findings

• Sarcopenia was independently associated with decreased ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL), as measured by the Barthel Index (BI) and BI-dyspnea (BI-d), in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and pulmonary function. Moreover, skeletal muscle mass index (SMI) was associated with BI, while gait speed was associated with BI-d in both men and women. These findings indicate that muscle mass and functional performance have distinct roles in basic ADL and ADL affected by dyspnea.

What is known and what is new?

• Sarcopenia is a known risk factor for reduced physical performance and quality of life in patients with chronic respiratory disease. However, its impact on performance of ADL in patients with ILD has been unclear.

• This study demonstrates that sarcopenia significantly impairs ADL in patients with ILD. Its findings suggest that the SMI and gait speed contribute to ADL and dyspnea-related ADL in different ways, highlighting the importance of assessing sarcopenia and its components in clinical practice.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Screening for sarcopenia and assessing its components should be integrated into the routine management of patients with ILD. This approach may help to identify individuals at risk for ADL impairment and facilitate targeted interventions to improve their quality of life. Future studies should explore intervention strategies that address both preservation of muscle mass and enhancement of functional performance.

Introduction

Sarcopenia is a progressive generalized skeletal muscle disorder that manifests as accelerated loss of muscle mass and function (1). Sarcopenia increases the risks of falls, fractures, and mortality and impairs the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) in community-dwelling elderly people (1-3). It is not only caused by aging, but also occurs in various disease states. In patients with chronic respiratory disease, especially those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), sarcopenia is caused by disuse of skeletal muscle as a result of physical inactivity associated with exertional dyspnea, depletion associated with increased ventilatory work, and decreased exercise capacity (4).

Interstitial lung diseases (ILD) constitute a heterogeneous group of pulmonary disorders that are characterized by various degrees of inflammation and/or fibrosis. Decreased lung compliance leads to increased respiratory workload, resulting in exertional dyspnea and reduced exercise tolerance. The clinical course of ILD is variable; however, many cases are progressive, with worsening respiratory function despite optimal treatment (5). Progression of ILD leads to exacerbation of dyspnea and limitations in ADL. In patients with ILD, these disabilities have been reported to be associated with a decrease in health-related quality of life and poorer prognosis (5). In previous studies, approximately 32.1% of patients with ILD had sarcopenia (6), which was associated with reduced exercise tolerance and increased mortality rates (7). However, reports on the clinical impact of sarcopenia as a complication of ILD are limited. Although limitations in ADL are a significant concern for many patients with ILD, there are no reports on the association between these outcomes and sarcopenia.

Diagnosis of sarcopenia in the Asian population was defined by the Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia (AWGS) consensus in 2019. The AWGS 2019 criteria for diagnosis of sarcopenia include muscle strength, physical function, and skeletal muscle mass, with sarcopenia diagnosed as low skeletal muscle mass combined with either low muscle strength or poor physical function (1). There have been numerous reports on factors related to ADL and predictors of ADL decline among these components of sarcopenia in community-dwelling elderly individuals (8-10). However, there have been few similar studies in patients with respiratory disease and none specifically targeting those with ILD. Confirmation of these aspects could lead to more effective rehabilitation approaches for preventing sarcopenia in patients with ILD from an early stage.

This study aimed to determine the relationship of sarcopenia with basic ADL and with limitations of ADL by dyspnea in patients with ILD and to identify the components of sarcopenia that contribute to these outcomes. We hypothesized that sarcopenia would be associated with a decline in both basic ADL and ADL limitations due to dyspnea in patients with ILD. Furthermore, we posited that different components of sarcopenia would contribute uniquely to the impairments observed in basic ADL and those specifically related to dyspnea. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1631/rc).

Methods

Study cohort

Patients with ILD who were hospitalized at the Hyogo Medical University Hospital between June 2022 and February 2024 for chronic disease management purposes, including introduction or adjustment of long-term oxygen therapy, management of comorbidities, or participation in pulmonary rehabilitation, were included in the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: clinically stable over the previous 4 weeks; age ≥65 years; and able to perform the 6-min walk test (6MWT). The diagnostic criteria used for the various clinical types of ILD were consistent with those outlined in the International Consensus Statement (5). The following exclusion criteria were applied: severe cognitive impairment precluding assessment of clinical outcomes; thoracic surgery within the past 6 months; comorbidities affecting muscle strength, physical function, gait function, or dyspnea (e.g., musculoskeletal or neurological disorders, chronic heart failure, COPD or asthma); and a diagnosis of cancer. The ILD patients selected as study subjects were based on data obtained from hospital records. All patients had been diagnosed with ILD before the study period, with the sample size determined accordingly.

This cross-sectional retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hyogo Medical University (approval no. 4683; approval date April 26, 2024) and conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients during hospitalization, specifically informing them that their clinical data might be used for research purposes. As the study involved retrospective analysis of clinical data collected during routine medical care, no additional interventions or procedures were performed for research purposes. Additionally, to ensure transparency and respect for patient autonomy, an opt-out method was applied by publishing detailed study-related information on the hospital’s official website. This included the study’s objectives, methods, data handling policies, and clear instructions on how to decline participation at any time.

Measurements

Information on patient demographics [age, sex, and body mass index (BMI)] and clinical characteristics (comorbidities, treatments, and clinical type of ILD) was retrieved from the medical records. Patients were assessed using the Barthel Index (BI), Barthel Index-dyspnea (BI-d), 6MWT, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and EuroQol-5 Dimensions-5 Levels (EQ-5D-5L) survey, and evaluation of sarcopenia (handgrip strength, 6-meter walk, and skeletal muscle mass) from one week before discharge until the day before discharge. To address potential sources of bias, we ensured that all evaluators were trained and adhered to standardized assessment procedures, which helped minimize information bias. All patients completed pulmonary function tests using spirometry (CHESTAC-8900; Chest, Tokyo, Japan) according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) criteria within 2 weeks of these assessments (11). The diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide (DLco) was also measured (CHESTAC-8900). The percentage of predicted FVC (%FVC), percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1.0 s (%FEV1.0), and percentage of predicted DLco (%DLco) were calculated based on the patient’s height, age, and sex according to standardized methods in Japan (12). The Gender, Age, and Physiology (GAP) score was calculated based on sex, age, subtype of ILD, and pulmonary function test results (13). The 6MWT was performed in accordance with the ATS guidelines (14). Risk of anxiety and depression was assessed using HADS (15). HADS is a 14-item tool that consists of two parts, each with seven items: HADS-A (anxiety) and HADS-D (depression). Each item is rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 to 3, with anxiety and depression rated according to the total score of HADS-A and HADS-D, respectively (15). Higher scores indicate more severe distress. The EQ-5D-5L measures five dimensions of health-related quality of life, namely, mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression (16). Each item is answered on a 5-point scale, and index values are calculated using an algorithm. We used the Japanese version, which has been thoroughly reviewed for validity and reliability (17).

Diagnosis of sarcopenia based on AWGS 2019 criteria

Sarcopenia was diagnosed based on the criteria set by the AWGS 2019, which define sarcopenia as the presence of low muscle mass, low muscle strength, and/or low physical performance (1). Measurements included skeletal muscle mass index (SMI), handgrip strength, and usual gait speed.

To establish diagnostic cut-off values, AWGS 2019 utilized reference equations derived from large-scale, population-based studies across Asian countries. These values were specifically tailored to reflect the normative data of Asian populations, accounting for regional differences in body composition and physical function (1). Another distinguishing feature of AWGS 2019, compared to the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) criteria, is its acceptance of bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) as an alternative to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for assessing skeletal muscle mass. This adaptation enhances the feasibility of sarcopenia diagnosis in clinical and research settings in Asia, where access to DXA may be limited (18).

In this study, skeletal muscle mass was measured using a multifrequency BIA system (InBody S10; InBody Japan, Tokyo, Japan) in the supine position. To ensure accurate skeletal muscle mass measurements, we followed standard protocols by conducting BIA assessments under fasting conditions and after a sufficient rest period following exercise. The SMI was calculated using the following formula: appendicular skeletal muscle mass (kg)/height2 (m2). The cutoff value for low muscle mass was <7.0 kg/m2 for men and <5.7 kg/m2 for women. Handgrip strength was measured in the standing position with full elbow extension using an electronic dynamometer (TKK 5101; Takei, Tokyo, Japan). The measurements were obtained twice for each hand, with the largest value used as the grip strength value for analysis. The cutoff value for low muscle strength was defined as <28.0 kg for men and <18.0 kg for women. Usual gait speed was measured by having the patients walk a 10-meter corridor at their usual speed. The time taken to walk a 6-meter section, excluding the acceleration and deceleration phases, was measured twice, and the average value was calculated. The cutoff for low physical performance was defined as <1.0 m/s for both sexes. Based on this cutoff value, the patients were classified into a sarcopenia group and a non-sarcopenia group.

BI and BI-d

The ability to perform basic ADL was evaluated using the BI (19), which comprises scores on a scale of 0–100, with higher scores indicating better functioning in ADL. The BI items include feeding, grooming, dressing, transferring, bladder management, bowel management, toileting, bathing, walking, and climbing up and down stairs. In 2016, Vitacca et al. developed the BI-d based on the BI items as a respiratory disease-specific scale for ADL. The BI-d comprises a 5-point evaluation of breathlessness and movement speed for each ADL item, with a total score ranging from 0 to 100 points and higher scores indicate greater dyspnea during performance of ADL (20). The Japanese version of the BI-d was created by Yamaguchi et al., and its reliability and validity have been demonstrated in Japanese patients with chronic respiratory disease (21). On the day of evaluation, BI and BI-d were measured by either observation of ADL or by interview in accordance with the guidelines (21).

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics are reported as the percentage for categorical data and as the median (interquartile range) for continuous data. Outcomes were compared between the sarcopenia group and the non-sarcopenia group using the Mann-Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test. The association between sarcopenia and the BI or BI-d was assessed by multivariate linear regression analysis, with interaction terms included to evaluate differences by such as age and sex. Univariate analyses were performed first to determine the covariates and identified that BMI and %FVC were associated with the BI while BMI, %FVC, and %DLco were associated with the BI-d. Owing to sample size limitations, BMI and %FVC were selected as covariates, along with age and sex, which were included as basic demographic variables. Selection of these covariates was based on clinical relevance and the findings in previous studies (22-24). Variance inflation factor values were computed to assess multicollinearity among the covariates. Values between 1 and 3 were considered indicative of no multicollinearity. We then performed further univariate analyses to examine the relationship between each component of sarcopenia and the BI and BI-d separately for men and women, given that the components of sarcopenia, excluding walking ability, vary according to sex. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 16.0 software (SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan). A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

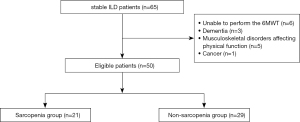

Figure 1 shows the patient flow. During the study period, 65 patients were hospitalized with stable ILD. After exclusion of 6 patients who were unable to be perform the 6MWT, 3 in whom outcomes could not be assessed accurately because of dementia, 5 with musculoskeletal disorders affecting physical function and gait function, and 1 with cancer, 50 Japanese patients with ILD (median age, 76 years; median %FVC, 71.6%) were enrolled. Sarcopenia was diagnosed in 21 patients (42.0%). All variables of interest had complete data, with no missing values reported. Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median BMI was significantly lower in the sarcopenia group than in the non-sarcopenia group (17.9 vs. 22.7, P<0.01). There was no significant between-group difference in ILD subtype, medication, or pulmonary function. All components of sarcopenia, including grip strength, gait speed, and SMI, were lower in men in the sarcopenia group. For women, only SMI showed a significant difference between the two groups.

Table 1

| Variable | All patients (n=50) | Sarcopenia group (n=21) | Non-sarcopenia group (n=29) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 76.0 (67.0–82.0) | 78.0 (68.0–83.5) | 76.5 (65.6–80.8) | 0.25 |

| Male sex, % | 58.0 | 66.7 | 51.7 | 0.39 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 20.4 (17.1–23.2) | 17.9 (14.5–20.7) | 22.7 (20.0–24.2) | <0.01* |

| CCI | 3 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 3 (3–4) | 0.93 |

| Type of ILD, % | ||||

| IPF/CTD-ILD/NSIP/PPFE/CHP/unclassifiable | 40.0/18.0/14.0/4.0/2.0/22.0 | 42.9/9.5/19.1/4.8/0/23.8 | 37.9/24.1/10.3/0/6.9/20.7 | 0.63 |

| Use of corticosteroids, % | 38.0 | 23.8 | 48.3 | 0.14 |

| Use of antifibrotic agents, % | 42.0 | 47.6 | 37.9 | 0.56 |

| LTOT, % | 44.0 | 47.6 | 41.4 | 0.78 |

| GAP score | 3.5 (2–5) | 4 (3–5) | 3 (1–5) | 0.16 |

| %FVC, % | 71.6 (53.2–86.7) | 64.7 (43.9–79.8) | 74.5 (57.9–91.6) | 0.08 |

| FEV1.0, % predicted | 67.7 (60.2–90.5) | 67.7 (48.5–89.1) | 68.2 (60.7–90.7) | 0.40 |

| FEV1.0/FVC, % | 81.6 (76.4–90.8) | 85.0 (76.0–93.0) | 80.9 (76.9–89.2) | 0.54 |

| DLco, % predicted | 55.2 (44.2–66.0) | 54.1 (37.8–68.7) | 56.3 (46.7–66.1) | 0.83 |

| Grip strength, kg | ||||

| Men | 22.5 (18.9–28.5) | 19.4 (16.1–22.4) | 28.4 (24.5–33.0) | <0.01* |

| Women | 18.9 (15.5–21.7) | 15.6 (15.3–20.3) | 19.4 (15.9–21.9) | 0.47 |

| Gait speed, m/s | ||||

| Men | 1.04 (0.97–1.18) | 0.98 (0.91–1.04) | 1.18 (1.12–1.25) | <0.01* |

| Women | 1.03 (0.82–1.18) | 1.03 (0.82–1.04) | 1.07 (0.97–1.29) | 0.17 |

| SMI, kg/m2 | ||||

| Men | 6.7 (6.3–7.5) | 6.6 (5.6–6.7) | 7.5 (6.9–8.1) | <0.01* |

| Women | 5.8 (5.4–6.2) | 5.1 (4.5–5.5) | 6.1 (5.8–6.3) | 0.02* |

Data are presented as the median (interquartile ranges) or frequency (percentage). The P value represents the comparison between the sarcopenia group and the non-sarcopenia group. Statistically significant findings (P<0.05) are marked with asterisk. BMI, body mass index; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ILD, interstitial lung disease; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; CTD-ILD, connective tissue disease; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; PPFE, pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis; CHP, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis; LTOT, long-term oxygen therapy; GAP score, Gender, Age and Physiology score; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1.0, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; DLco, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; SMI, skeletal muscle mass index.

Table 2 compares the clinical outcomes between the sarcopenia and non-sarcopenia groups. BI scores were significantly lower and BI-d scores were significantly higher in the sarcopenia group (85 vs. 90 and 45 vs. 10, respectively, both P<0.01). In the sub-items of BI, scores for Mobility, Stairs, and Toilet use were significantly lower in the sarcopenia group. In the sub-items of BI-d, scores for dressing, feeding, bladder, bowels, mobility, stairs, toilet use, and transfers were significantly higher in the sarcopenia group. There was a significant decrease in the distance walked on the 6MWT in the sarcopenia group (245.0 vs. 318.5 m, P=0.03). The HADS-D scores were significantly higher in the sarcopenia group (6.0 vs. 5.0, P=0.02); however, there was no significant between-group difference in HADS-A scores. The EQ-5D-5L score was lower in the sarcopenia group, as were the scores for the mobility (P<0.01), self-care (P<0.01), and usual activities (P=0.02) sub-items.

Table 2

| Clinical outcomes | Sarcopenia group (n=21) | Non-sarcopenia group (n=29) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| BI | |||

| Total score | 85.0 (77.5–87.5) | 90.0 (85.0–92.5) | <0.01* |

| Dressing | 10.0 (10.0–10.0) | 10.0 (10.0–10.0) | 0.17 |

| Bathing | 5.0 (2.5–5.0) | 5.0 (5.0–5.0) | 0.19 |

| Feeding | 5.0 (5.0–10.0) | 5.0 (5.0–10.0) | 0.58 |

| Grooming | 5.0 (5.0–5.0) | 5.0 (5.0–5.0) | 0.99 |

| Bladder | 10.0 (10.0–10.0) | 10.0 (10.0–10.0) | 0.88 |

| Bowels | 5.0 (5.0–5.0) | 5.0 (5.0–7.5) | 0.87 |

| Mobility | 10.0 (10.0–15.0) | 15.0 (10.0–15.0) | 0.03* |

| Stairs | 5.0 (5.0–10.0) | 10.0 (5.0–10.0) | 0.04* |

| Toilet use | 10.0 (5.0–10.0) | 10.0 (10.0–10.0) | <0.01* |

| Transfers | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 0.17 |

| BI-d | |||

| Total score | 45.0 (22.5–49.5) | 10.0 (8.0–30.0) | <0.01* |

| Dressing | 2.0 (0–5.0) | 0 (0–2.0) | 0.02* |

| Bathing | 3.0 (0–4.0) | 0 (0–3.0) | 0.08 |

| Feeding | 2.0 (0–2.0) | 0 (0–0) | 0.02* |

| Grooming | 1.0 (0–3.0) | 0 (0–1.0) | 0.07 |

| Bladder | 2.0 (0–5.0) | 0 (0–2.0) | 0.03* |

| Bowels | 5.0 (0–5.0) | 0 (0–2.0) | <0.01* |

| Mobility | 8.0 (8.0–12.0) | 3.0 (3.0–12.0) | <0.01* |

| Stairs | 10.0 (8.0–10.0) | 5.0 (5.0–9.0) | <0.01* |

| Toilet use | 2.0 (0–5.0) | 0 (0–2.0) | 0.02* |

| Transfers | 0 (0–3.0) | 0 (0–0) | <0.01* |

| 6MWD, m | 245.0 (165.0–338.0) | 318.5 (234.5–381.5) | 0.03* |

| HADS-A | 5.0 (4.0–7.0) | 4.5 (3.0–6.0) | 0.07 |

| HADS-D | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) | 5.0 (3.3–6.8) | 0.02* |

| EQ-5D5L (1/2/3/4/5), % | |||

| Index score | 0.58 (0.45–0.77) | 0.84 (0.70–0.88) | <0.01* |

| Mobility | 0/14.3/38.1/28.6/19.0 | 3.6/53.6/21.4/21.4/0 | <0.01* |

| Self-care | 14.3/28.6/42.9/14.3/0 | 60.7/21.4/14.3/3.6 | <0.01* |

| Usual activities | 19.1/23.8/42.9/9.5/4.8 | 53.6/32.1/10.7/3.6/0 | 0.02* |

| Pain/discomfort | 28.6/47.6/19.2/4.8/0 | 53.4/35.7/10.7/0/0 | 0.06 |

| Anxiety/depression | 19.1/52.3/23.8/4.8/0 | 46.4/42.9/10.7/0/0 | 0.11 |

Data are presented as the median (interquartile range). The P value represents the comparison between the sarcopenia group and the non-sarcopenia group. Statistically significant findings (P<0.05) are marked with asterisk. BI, Barthel Index; BI-d, Barthel Index-dyspnea; 6MWD, six-minute walk distance; EQ-5D5L, EuroQol-5 Dimesions5 Levels; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.

Tables 3,4 show the results of the multiple linear regression analyses. After adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and %FVC, sarcopenia was significantly associated with the BI and BI-d scores (β=−0.30, P=0.03 and β=0.45, P<0.01, respectively). Furthermore, %FVC was associated with the BI-d score (β=−0.37, P<0.01).

Table 3

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | |||

| Sarcopenia | −0.43 | <0.01 | −0.34 | 0.02 | −0.30 | 0.03* | ||

| Age | −0.05 | 0.68 | −0.05 | 0.65 | −0.07 | 0.60 | ||

| Sex (male) | −0.17 | 0.18 | −0.17 | 0.17 | −0.20 | 0.11 | ||

| BMI | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.26 | ||||

| %FVC | 0.20 | 0.15 | ||||||

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex. Model 2: adjusted for age, sex and BMI. Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and % FVC. Statistically significant P values (P<0.05) are marked with asterisk. BMI, body mass index; %FVC, percent predicted forced vital capacity.

Table 4

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | P value | β | P value | β | P value | |||

| Sarcopenia | 0.55 | <0.01* | 0.52 | <0.01* | 0.45 | <0.01* | ||

| Age | −0.13 | 0.31 | −0.15 | 0.33 | −0.11 | 0.36 | ||

| Sex (male) | −0.15 | 0.23 | −0.13 | 0.24 | −0.10 | 0.43 | ||

| BMI | −0.08 | 0.57 | 0.04 | 0.76 | ||||

| %FVC | −0.37 | <0.01* | ||||||

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex. Model 2: adjusted for age, sex and BMI. Model 3: adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and % FVC. Statistically significant P values (P<0.05) are marked with asterisk. BMI, body mass index; %FVC, percent predicted forced vital capacity.

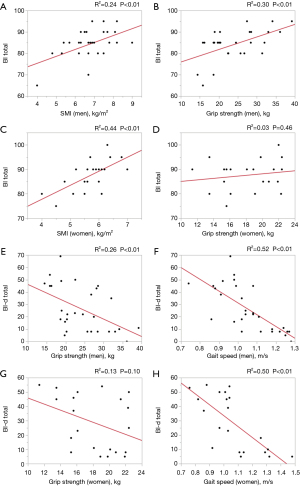

Figure 2 shows the associations of the three components of sarcopenia with the BI and BI-d scores. SMI was found to be significantly associated with the total BI score (men, R2=0.24, β=0.49, P<0.01; women, R2=0.44, β=0.66, P<0.01), while gait speed was significantly associated with the total BI-d score (men, R2=0.52, β=−0.72, P<0.01; women, R2=0.50, β=−0.71, P<0.01). In men, grip strength was associated with both BI and BI-d (R2=0.30, β=0.55, P<0.01 and R2=0.26, β=−0.51, P<0.01, respectively).

Discussion

This study found that patients with both ILD and sarcopenia experience significantly ADL impairment, diminished exercise tolerance, poorer health-related quality of life, and more pronounced depressive symptoms in comparison with patients without sarcopenia. Sarcopenia was associated with basic ADL and dyspnea-related limitations in patients with ILD after adjusting for age, sex, BMI and %FVC. Importantly, this research is the first to elucidate the relationship between sarcopenia and its components with ADL in patients who have ILD. We performed a thorough evaluation of ADL, considering not only functional impairments but also the specific limitations imposed by dyspnea. Our findings highlight an urgent need for early nutritional and rehabilitative interventions in patients with ILD to mitigate sarcopenia and its adverse impact on day-to-day functioning. Addressing both functional limitations and the unique challenges posed by dyspnea could enhance patient management and optimize care strategies.

Previous studies have demonstrated an association between sarcopenia and ADL in community-dwelling older adults (8-10,22,23). Sarcopenia leads to decreased energy expenditure as a result of a reduction in the basal metabolic rate because of loss of skeletal muscle mass, which in turn causes a decrease in appetite and further progression of sarcopenia. Moreover, the muscle weakness and physical function decline associated with sarcopenia contribute to impairment of ADL, leading to reduced activity levels and perpetuating this vicious cycle (25). Patients with chronic respiratory disease, including those with ILD, experience a further decline in activity levels as a result of dyspnea during daily activities, which significantly impacts their ADL (26). Our study confirms that sarcopenia in patients with ILD is independently associated with a decline in basic ADL even after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and %FVC.

Although reports on the impact of sarcopenia on outcomes in patients with ILD are limited, Fujita et al. found that sarcopenia correlated with a reduced 6MWD and poorer patient-reported outcomes, including St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire-activity and HADS-D scores, in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (24). Our study identified similar trends, with reductions in 6MWD, increased HADS-D scores, and decreased EQ-5D-5L scores in the sarcopenia group. These findings suggest that sarcopenia affects not only functional but also psychological and social parameters, although further research is needed to explore these multifaceted interactions (27).

The association between sarcopenia and exertional dyspnea in patients with ILD has been reported elsewhere (6,7). Tests such as the 6MWT (14) and sit-to-stand test (28) are used to evaluate exertional dyspnea but focus on assessment of a single task primarily using the lower limbs. However, ADL tasks are complex and involve continuous movements, including movements of the upper limbs, trunk inclination, and breath-holding, leading to limitations in thoracic and diaphragmatic motion or disruptions in breathing rhythm (29). The relationship between dyspnea during these ADL tasks and sarcopenia in patients with ILD has not been thoroughly investigated. Our study found an association between sarcopenia and the total BI-d score after adjusting for age, sex, BMI and pulmonary function, indicating that sarcopenia is related to exertional dyspnea during ADL. This finding suggests the need for individualized ADL training tailored to specific limitations and environments to improve dyspnea during activities.

There are no reports demonstrating an association between any of the components of sarcopenia and ADL in patients with ILD. In this study, SMI was associated with the BI score in both sexes, whereas grip strength was associated with the BI score only in men. Previous study has reported that skeletal muscle atrophy and loss of muscle mass are associated with impaired ADL in patients with COPD (30). This impairment of ADL is associated with cachexia, which is characterized by increased energy expenditure due to inflammatory cytokines (31,32), and may also contribute to the ADL decline in patients with ILD (33). Conversely, the BI-d score was associated with gait speed in both sexes, showing a moderate fit. Usual gait speed assessed by the 4-meter walk test was reported to identify patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and significantly worse exercise performance, dyspnea, health status, and prognosis scores despite similar pulmonary function and radiological parameters (34). Yoshida et al. reported that the physical activity level of patients with chronic respiratory disease can be predicted by gait speed (35). These studies suggest that gait speed may be related to limitations in performance of ADL owing to dyspnea in patients with ILD. Fischer et al. reported that patients with ILD have worse gait instability and a slower gait speed to alleviate dyspnea (36). Approaches targeting gait stability could potentially lead to improvements in clinical outcomes for patients with ILD. Grip strength was associated with both BI and BI-d scores only in men, possibly because women generally have lower muscle strength.

This study had several limitations. First, it had a cross-sectional design and a limited sample size, which may limit the generalizability of its findings. Future longitudinal studies with larger sample sizes should be conducted to further explore the relationship between sarcopenia and ADL. Additionally, the lack of a control group, such as COPD patients or healthy individuals, limited our ability to compare sarcopenia-related ADL impairments across different populations. Future studies should include such control groups to provide broader context and strengthen the generalizability of findings. Second, while the BI-d has demonstrated reliability and validity as an indicator of the ability of patients with chronic respiratory disease in Japan to perform ADL, caution is needed when applying this tool in patients with ILD because the majority of participants in the original validation study had COPD. However, Japan has very few disease-specific ADL scales for respiratory diseases that are both established domestically and widely recognized internationally with proven reliability and validity. Given this limitation, the BI-d remains one of the most valuable tools currently available for assessing ADL in ILD patients. The BI-d has been widely used across a range of respiratory diseases internationally, and future research should focus on developing ADL assessment scales specifically for ILD. Third, the ADL assessments included not only observations of performance of ADL but also patient-reported information, which may have introduced a degree of subjectivity. Moreover, dynamic respiratory physiological parameters during ADL could not be measured owing to the COVID-19 pandemic. Fourth, all evaluations were conducted during hospitalization because outpatient assessments were not feasible due to restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. As assessments took place in a hospital environment rather than patients’ usual living settings, factors such as reduced daily activity or hospital routines may have influenced physical performance. Although evaluations were performed near discharge when patients were clinically stable, potential effects of hospitalization cannot be entirely ruled out. Despite these limitations, our study provides significant insights into the association between sarcopenia and performance of ADL in patients with ILD. Our findings underscore the importance of incorporating comprehensive assessments of sarcopenia in the management of patients with ILD. Future research should address these limitations and validate the relationships observed in this study to enhance our understanding and improve clinical outcomes in this patient population.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that sarcopenia significantly impacts ADL in patients with ILD, leading to reduced functional capacity, poorer health-related quality of life, and worsening of depressive symptoms. Notably, sarcopenia remained associated with ADL even after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and %FVC. Importantly, we identified that specific components of sarcopenia, namely, SMI and gait speed, associated with performance of ADL. This research is the first to elucidate these relationships in patients with ILD and underscores the need for tailored interventions that address both functional limitations and dyspnea. While our findings are limited by the cross-sectional design of this study, they highlight the importance of incorporating comprehensive assessments of sarcopenia into clinical management to enhance patient outcomes. Future studies should focus on larger, longitudinal cohorts to confirm our findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the staff of the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Hyogo Medical University Hospital, for their assistance with this research.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1631/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1631/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1631/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1631/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This cross-sectional study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hyogo Medical University (approval no. 4683; approval date April 26, 2024) and conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. Using the opt-out method, participants were given the opportunity to decline to participate in the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Chen LK, Woo J, Assantachai P, et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020;21:300-307.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kelley GA, Kelley KS. Is sarcopenia associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and functional disability? Exp Gerontol 2017;96:100-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu W, Chen T, Cai Y, et al. Sarcopenia in Community-Dwelling Oldest Old Is Associated with Disability and Poor Physical Function. J Nutr Health Aging 2020;24:339-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marengoni A, Vetrano DL, Manes-Gravina E, et al. The Relationship Between COPD and Frailty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Chest 2018;154:21-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;188:733-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hanada M, Sakamoto N, Ishimoto H, et al. A comparative study of the sarcopenia screening in older patients with interstitial lung disease. BMC Pulm Med 2022;22:45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hanada M, Tanaka T, Kozu R, et al. The interplay of physical and cognitive function in rehabilitation of interstitial lung disease patients: a narrative review. J Thorac Dis 2023;15:4503-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Perez-Sousa MA, Venegas-Sanabria LC, Chavarro-Carvajal DA, et al. Gait speed as a mediator of the effect of sarcopenia on dependency in activities of daily living. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2019;10:1009-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bahat G, Tufan A, Kilic C, et al. Prevalence of sarcopenia and its components in community-dwelling outpatient older adults and their relation with functionality. Aging Male 2020;23:424-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang DXM, Yao J, Zirek Y, et al. Muscle mass, strength, and physical performance predicting activities of daily living: a meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020;11:3-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Laszlo G. Standardisation of lung function testing: helpful guidance from the ATS/ERS Task Force. Thorax 2006;61:744-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kubota M, Kobayashi H, Quanjer PH, et al. Reference values for spirometry, including vital capacity, in Japanese adults calculated with the LMS method and compared with previous values. Respir Investig 2014;52:242-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ryerson CJ, Vittinghoff E, Ley B, et al. Predicting survival across chronic interstitial lung disease: the ILD-GAP model. Chest 2014;145:723-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:111-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shiroiwa T, Fukuda T, Ikeda S, et al. Japanese population norms for preference-based measures: EQ-5D-3L, EQ-5D-5L, and SF-6D. Qual Life Res 2016;25:707-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019;48:16-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- MAHONEY FI. BARTHEL DW. FUNCTIONAL EVALUATION: THE BARTHEL INDEX. Md State Med J 1965;14:61-5.

- Vitacca M, Paneroni M, Baiardi P, et al. Development of a Barthel Index based on dyspnea for patients with respiratory diseases. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11:1199-206. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi T, Yamamoto A, Oki Y, et al. Reliability and Validity of the Japanese Version of the Barthel Index Dyspnea Among Patients with Respiratory Diseases. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2021;16:1863-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiu AF, Chou MY, Liang CK, et al. Barthel Index, but not Lawton and Brody instrumental activities of daily living scale associated with Sarcopenia among older men in a veterans' home in southern Taiwan. Eur Geriatr Med 2020;11:737-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morandi A, Onder G, Fodri L, et al. The Association Between the Probability of Sarcopenia and Functional Outcomes in Older Patients Undergoing In-Hospital Rehabilitation. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:951-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fujita K, Ohkubo H, Nakano A, et al. Frequency and impact on clinical outcomes of sarcopenia in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chron Respir Dis 2022;19:14799731221117298. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M146-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Axelsson GT, Putman RK, Araki T, et al. Interstitial lung abnormalities and self-reported health and functional status. Thorax 2018;73:884-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fettes L, Bayly J, Chukwusa E, et al. Predictors of increasing disability in activities of daily living among people with advanced respiratory disease: a multi-site prospective cohort study, England UK. Disabil Rehabil 2024;46:4735-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goldberg A, Chavis M, Watkins J, et al. The five-times-sit-to-stand test: validity, reliability and detectable change in older females. Aging Clin Exp Res 2012;24:339-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Skumlien S, Hagelund T, Bjørtuft O, et al. A field test of functional status as performance of activities of daily living in COPD patients. Respir Med 2006;100:316-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kennedy CC, Novotny PJ, LeBrasseur NK, et al. Frailty and Clinical Outcomes in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2019;16:217-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schols AM, Broekhuizen R, Weling-Scheepers CA, et al. Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr 2005;82:53-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshida T, Tabony AM, Galvez S, et al. Molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways of angiotensin II-induced muscle wasting: potential therapeutic targets for cardiac cachexia. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2013;45:2322-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kitahara S, Abe M, Kono C, et al. Prognostic impact of the cross-sectional area of the erector spinae muscle in patients with pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis. Sci Rep 2023;13:17289. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nolan CM, Maddocks M, Maher TM, et al. Phenotypic characteristics associated with slow gait speed in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirology 2018;23:498-506. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yoshida C, Ichiyasu H, Ideguchi H, et al. Four-meter gait speed predicts daily physical activity in patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Respir Investig 2019;57:368-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fischer G, de Queiroz FB, Berton DC, et al. Factors influencing self-selected walking speed in fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Sci Rep 2021;11:12459. [Crossref] [PubMed]