Impact of spontaneous ventilation with intubation on perioperative results in uniportal VATS lobectomy compared to general anaesthesia using a double-lumen tube

Highlight box

Key findings

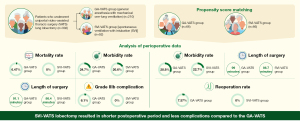

• Complications during the perioperative period were fewer with spontaneous ventilation and intubation during lung resection compared to cases using relaxation.

What is known and what is new?

• Non-intubated thoracic surgery with spontaneous ventilation results in a reduced inflammatory response, but airway safety is a concern during this procedure.

• Spontaneous ventilation with intubation (SVI) during thoracic surgery maintains the benefits of spontaneous ventilation while addressing airway safety.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• SVI during thoracic surgery is a safe and easily reproducible procedure, suggesting it should be more widely adopted.

Introduction

Background

Maintaining ventilation and securing proper anesthesia during open thoracic surgery have been ongoing challenges since the iconic experiment of the negative-pressure chamber by Sauerbruch (1). Curare and its derivatives enabled relaxation, and double-lumen tracheal intubation and positive pressure ventilation became standard anesthesia procedures by the mid-1980s (2,3).

Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS), as a subset of minimally invasive thoracic surgery (MITS), is on the way to becoming the gold standard for pulmonary resections and other intrathoracic procedures in the majority of procedures. Intra- and perioperative means are applied, such as high-precision intrabronchial and intravascular interventions and enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) (4), with the common aim of reducing perioperative stress and, consequently, lung injury. These developments have also challenged anesthetists to increase their contribution to minimizing pressure-related tissue damage during the procedure.

The cellular-level effect of positive pressure mechanical one-lung ventilation (mOLV) during chest surgery is a well-researched issue and a source of complications parallel to the adverse effects of tracheal intubation (5). Non-intubated thoracoscopic surgery (NITS) aims to reduce pressure-induced lung injury and mechanical insult to tracheobronchial wall structures (6).

Rationale and knowledge gap

NITS is unable to fulfil many of its promises, mainly regarding airway safety and safety when an intratracheal intubation conversion is needed, which occurs with a reported frequency between 1.8–11% (7).

Accepting the concerns of the anesthesia team, in our current spontaneous ventilation practice, the safe airway was provided with double lumen tube intubation after a short initial relaxation; however, during the major part of the procedure, the patients ventilate spontaneously, i.e., spontaneous ventilation with intubation (SVI) (8).

Objectives

In this study, the perioperative results of the SVI method in VATS lobectomy were analyzed. We present this article in accordance with the TREND reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1396/rc).

Methods

Study design

The study period was between July 5, 2015, and September 1, 2023. During these 8 years, three types of VATS lobectomies were performed in the Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, University of Szeged, Hungary, depending on the skill and availability of the anesthesiology team.

Between July 5, 2015, and December 17, 2019, only uniportal relaxed, intubated, and mechanically one-lung ventilated VATS lobectomies were performed. The patients who were operated on during this period formed the VATS under general anesthesia (GA-VATS) group of the current study.

Between December 17, 2019, and October 3, 2021, two types of VATS lobectomies were performed: uniportal, relaxed, intubated, mechanically one-lung ventilated, and NITS-VATS lobectomies. No patients from this period were included in the study.

On October 2, 2021, the spontaneous ventilation with intubation VATS (SVI-VATS) lobectomy method was started, and between October 2, 2021, and September 21, 2023, two types of VATS lobectomies were performed: uniportal, relaxed, intubated, mechanically one-lung ventilated, and SVI-VATS lobectomies, depending on the skill and availability of the anesthesiology team. The SVI-VATS lobectomies formed the SVI-VATS group in the current study.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Human Investigation Review Board of the University of Szeged (No. 4703/2020.01.20), and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Data from 302 patients were collected from their charts and online documentation and analyzed. After analyzing the data, a propensity score matching procedure was performed to compare the two methods. A 1:1 sample was selected based on the baseline characteristics of the patient population, including age, sex, BMI, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), preoperative forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1%), and the affected lung lobe,

The primary endpoint of the study was the analysis of perioperative morbidity, particularly IIIb grade complications, in all patients and after propensity score matching. The secondary endpoints included operative time, drainage time, number of removed mediastinal lymph nodes, permanent air leak, and morbidity grades I–IIIa.

Patient selection

In this retrospective study of VATS lobectomies, the data of 302 consecutive eligible patients were analyzed. The inclusion criteria for the SVI-VATS group were a body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2; American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification 1 and 2, and a lack of serious cardiorespiratory compromise. The same inclusion criteria were applied in the GA-VATS group, and other patients were excluded from the study.

In terms of tumor status, the selection of patients for GA-VATS and SVI-VATS was similar and followed the proposal of a consensus paper: patients without advanced-stage lung cancer (<7 cm, N0, and N1 patients) were scheduled (9). Patients who underwent neoadjuvant treatment or conversion to an open procedure or from the SVI-VATS to GA-VATS procedure were also excluded.

The TNM classification followed the eighth edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer (10).

The Clavien-Dindo classification for complications was applied to assess the relevant actions during the postoperative course (11). The following complications were considered under morbidity: pneumonia, atrial fibrillation, prolonged air leak, drain reinsertion after removal of the intraoperative drain, transfusion, chylothorax, empyema, subcutaneous emphysema, fever requiring antibiotic administration, COVID infection, diabetes mellitus imbalance necessitating a change in the preoperative treatment, and wound infection.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for discrete variables, and a propensity score matching procedure (1:1 sample) logistic regression model with the nearest neighbor method and a caliper of 0.1. P<0.05 was respected as significant.

Anesthesia

Based on the method of anesthesia, the patient population was divided into the GA-VATS and SVI-VATS groups. Out of the 302 patients who underwent VATS lobectomy during these periods, 210 belonged to the GA-VATS group, and 92 were in the SVI-VATS group.

In the GA-VATS group, the surgery was performed under double-lumen tube intubation and relaxation with mOLV, which is the standard anesthesia in lung cancer surgery worldwide.

In the SVI-VATS group, the surgery was performed with spontaneous ventilation under double-tube intubation anesthesia. The procedure was published and detailed before (12); here, a short summary is given. At the beginning of anesthesia, a short-acting muscle relaxant was used for the insertion of the double lumen tube. After intubation and patient positioning, 5 mg/kg lidocaine (2%) as maximal dose was administered at the site of the uniportal incision. After the thoracic cavity was opened, 4–5 mL of bupivacaine 0.5%, with a maximum dose of 2.5 mg/kg, was used as an anesthetic around the vagus nerve at the level of the trachea on the right side and in the aortopulmonary window on the left side, and in each intercostal space between the 2nd and 5th ribs. Instead of epidural anesthesia and paravertebral blockades, we prefer regional blocks owing to their less pronounced hemodynamic effects, adverse effects, and fewer contraindications. The preparation for epidural and paravertebral techniques is more time-consuming. Additionally, this approach facilitates earlier patient mobilization and helps minimize complication rates.

If the spontaneous ventilation of the patient was reestablished before the chest cavity was entered and the patient being to cough, a short-acting muscle relaxant was administered again to allow sufficient time to for nerve anesthesia. After spontaneous breathing, anesthesia was maintained using solely propofol in a target-controlled manner without any relaxation. The target concentration was generally set between 4 and 6 µg/mL. By gradually increasing the dose of propofol until reaching the target bisprectal index (BIS, Medtronic Vista) value, the incidence of hypoventilation and the development of apnea can be minimized.

Anesthesia depth was monitored using the BIS, with the target range set between 40 and 60.

The method of correction in cases of hypercapnia or hypoxia and the indication for relaxation are mentioned in the article (12).

In the GA group, the induction and maintenance of anesthesia were considerably similar to those in GA-VATS and SVI-VATS groups. In the GA-VATS group, anesthesia was induced with fentanyl (1–2 µg/kgbw) and propofol via target-controlled infusion (TCI) using the Schnider model (effect site: 4–6 µg/mL). For muscle relaxation, non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs), such as rocuronium-bromid or atracurium-besylate, were used.

Surgical method

All surgeries were performed in a standard VATS and uniportal manner. In both groups, the steps of the surgical procedure were the same, except for vagus nerve anesthesia, which was not applied in the GA-VATS group. In the GA-VATS and SVI-VATS groups, the patients received utility incision and intercostal anesthesia at the beginning of the surgery. After the lobectomy, a chest drain was inserted and connected to digital suction. The drain was removed if the air leak stopped and/or the volume of the fluid was less than 400–500 mL per day (8).

Results

Among the 302 patients, 161 (53.3%) were women and 141 (46.7%) were men, with an average age of 64.88±10.47 years.

In the GA-VATS group, there were 210 patients (69.5%), while the SVI-VATS group consisted of 92 patients (30.5%). The patient characteristics are detailed in Table 1. The BMI was significantly different between the groups, but it had no clinical importance in terms of the surgery. There was no difference in the other basic patients’ characteristics between the 2 groups. The number of resected mediastinal lymph nodes was 12.76±7.41 and 12.79±8.48 (P=0.97) in the GA-VATS and SVI-VATS groups, respectively.

Table 1

| Characteristics | GA-VATS (n=210) | SVI-VATS (n=92) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.28±10.91 | 66.27±9.26 | 0.12 |

| Gender | 0.56 | ||

| Male | 93 (44.2) | 48 (52.2) | |

| Female | 117 (55.7) | 44 (47.8) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 4.54±2.37 | 5.47±2.11 | 0.97 |

| Weight (kg) | 77.11±17.08 | 71.23±14.09 | 0.006 |

| Height (cm) | 167.59±9.53 | 167.27±9.32 | 0.32 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.37±5.20 | 25.61±3,96 | 0.005 |

| FEV1% | 84.76±20.28 | 87.05±19.41 | 0.39 |

| DLCO (mL/min/kPa) | 74.14±22.66 | 78.33±19.14 | 0.36 |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (percentage). GA-VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under general anesthesia; SVI-VATS, spontaneous ventilation with intubation video-assisted thoracic surgery; FEV1%, forced expiratory volume in 1 second %; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide.

Types of the lobectomies (Table 2) and the final stages of lung cancer are listed in Table 3.

Table 2

| Type of lobectomy | All (n=302) | GA-VATS (n=210) | SVI-VATS (n=92) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RUL | 106 (35%) | 80 (38%) | 26 (28.2%) | 0.12 |

| RML | 26 (8.6%) | 15 (7.14%) | 11 (11.9%) | 0.16 |

| RLL | 65 (21.5%) | 33 (15.7%) | 32 (34.7%) | 0.001 |

| LUL | 62 (20.52%) | 45 (21.4%) | 17 (18.4%) | 0.55 |

| LLL | 43 (14.2%) | 37 (17.6%) | 6 (6.52%) | 0.001 |

GA-VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under general anesthesia; SVI-VATS, spontaneous ventilation with intubation video-assisted thoracic surgery; RUL, right upper lobectomy; RML, right middle lobectomy; RLL, right lower lobectomy; LUL, left upper lobectomy; LLL, left lower lobectomy.

Table 3

| Stage | All primer malignancy (n=243) | GA-VATS (n=167) | SVI-VATS (=76) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage IA | 103 (42.38%) | 79 (47.3%) | 24 (31.57%) | 0.02 |

| Stage IB | 26 (10.69%) | 15 (8.9%) | 11 (14.47%) | 0.19 |

| Stage IIA | 24 (9.87%) | 15 (8.9%) | 9 (11.84%) | 0.48 |

| Stage IIB | 33 (13.5%) | 18 (10.8%) | 15 (19.7%) | 0.058 |

| Stage IIIA | 42 (17.2%) | 27 (16.6%) | 15 (19.7%) | 0.49 |

| Stage IIIB | 11 (4.52%) | 10 (5.9%) | 1 (1.32%) | 0.10 |

| Stage IVA | 4 (1.64%) | 3 (1.7%) | 1 (1.32%) | 0.78 |

| Stage IVB | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

*, due to the small element number, statistical analysis was omitted. GA-VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under general anesthesia; SVI-VATS, spontaneous ventilation with intubation video-assisted thoracic surgery.

The complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classification in the postoperative period are mentioned in Table 4. The Grade IIIb group consisted of 11 reoperations and 2 cases in which drain corrections were performed under GA in the operating room (shown in Table 5). These 2 cases were not considered as reoperations. There were no reoperations, pneumonias, or chylothoraxes after SVI-VATS lobectomies, and there were fewer chest drain reinsertions and transfusions after the SVI-VATS method compared to the GA-VATS cases. However, atrial fibrillation was more frequent after SVI-VATS than after GA-VATS. There was only one mortality in the GA-VATS group and none in the SVI-VATS group. The mortality case is described as follows: A 70-year-old man a BMI of 38 kg/m2, FEV1 of 47%, and DLCO of 55% underwent left lower VATS lobectomy. The patient had a history of a coronary by-pass surgery 10 years prior, as well as diabetes mellitus, varicectomy, COPD, and atrial fibrillation. The lung cancer stage was pT2bN0 squamous cell carcinoma. The operative time was 105 min, while the drainage time was 4 days. After a 2-day observation in the intensive care unit, the patient was re-admitted into the general ward. One week later, he discharged to the pulmonology department in stable condition. However, the patient died one week later due to cardiac insufficiency.

Table 4

| Grade of complications | All (n=302) | GA-VATS (n=210) | SVI-VATS (n=92) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complication | 71 (23.5%) | 52 (24.7%) | 19 (20.6%) | 0.32 |

| Grade I | 34 (11.2%) | 24 (11.4%) | 10 (10.8%) | 0.89 |

| Grade II | 16 (5.2%) | 6 (2.8%) | 10 (10.8%) | 0.06 |

| Grade IIIa | 12 (3.9%) | 10 (4.76%) | 2 (2.1%) | 0.27 |

| Grade IIIb | 13 (4.3%) | 13 (6.1%) | 0 | 0.01 |

| Grade IVa | 0 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Grade IVb | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Grade V | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

*, due to the small element number, statistical analysis was omitted. GA-VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under general anesthesia; SVI-VATS, spontaneous ventilation with intubation video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Table 5

| Complications | All (n=302) | GA-VATS (n=210) | SVI-VATS (n=92) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reoperation | 11 (3.6%) | 11 (5.2%) | 0 | 0.02 |

| Chest drain reinsertion | 16 (5.2%) | 14 (6.6%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0.10 |

| Transfusion | 8 (2.6%) | 6 (2.8%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0.73 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (0.99%) | 3 (1.4%) | 0 | 0.55 |

| Chylothorax | 2 (0.66%) | 2 (0.95%) | 0 | * |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 (1.32%) | 2 (0.95%) | 2 (2.7%) | 0.41 |

*, due to the small element number, statistical analysis was omitted. GA-VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under general anesthesia; SVI-VATS, spontaneous ventilation with intubation video-assisted thoracic surgery.

The final pathology of the lung lesions is described in Table 6.

Table 6

| Histology of the lesions | All (n=302) | GA-VATS (n=210) | SVI-VATS (n=92) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | 206 (68.21%) | 139 (66.2%) | 67 (72.8%) | 0.25 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 28 (9.27%) | 21 (10%) | 7 (7.6%) | 0.50 |

| Large cell carcinoma | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Small cell lung cancer | 1 (0.33%) | 0 | 1 (1.08%) | * |

| Carcinoid | 7 (2.31%) | 6 (2.85%) | 1 (1.08%) | 0.34 |

| Sarcoma | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Metastasis | 18 (5.9%) | 13 (6.2%) | 5 (5.43%) | 0.79 |

| Lymphoma | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Adenoma | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Hamartochondroma | 5 (1.65%) | 4 (1.9%) | 1 (1.08%) | * |

| Hamartolipoma | 4 (1.32%) | 2 (0.47) | 2 (2.17%) | 0.39 |

| Lymphangioma | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Fibrosis | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Sarcoidosis | 2 (0.66%) | 2 (0.95%) | 0 | * |

| Wegener granulomatosis | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Aspergilloma | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Inflammation | 13 (4.3%) | 9 (4.28%) | 4 (4.34%) | 0.98 |

| Tuberculosis | 8 (2.98%) | 5 (2.38%) | 3 (3.26%) | 0.66 |

| Pleural localized fibrous tumor | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | * |

| Sequestration | 1 (0.33%) | 0 | 1 (1.08%) | * |

*, due to the small element number, statistical analysis was omitted. GA-VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under general anesthesia; SVI-VATS, spontaneous ventilation with intubation video-assisted thoracic surgery.

The propensity score matching did not really change the incidence of the different complications. The rate of permanent air leaks became non-significant (P=0.001 vs. 0.10), but remained much lower than after mOLV (20.4% and 8.6% vs. 22.7% and 12.1%), and the lengths of surgery became significant (P=0.1 vs. 0.003) after the propensity score analysis (Table 7). The incidences of other complications like mortality, morbidity, reoperation, length of drainage time and drain reinsertion did not change after propensity score analysis.

Table 7

| Perioperative findings | Before propensity score analysis | After propensity score analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA-VATS (n=210) | SVI-VATS (n=92) | P value | GA-VATS (n=66) | SVI-VATS (n=66) | P value | ||

| Mortality | 1 (0.47%) | 0 | 0.050 | 0 | 0 | * | |

| Morbidity | 52 (24.7) | 19 (20.6) | 0.32 | 19 (28.8) | 15 (22.7) | 0.55 | |

| Reoperation | 11 (5.2) | 0 | 0.02 | 5 (7.57) | 0 | 0.058 | |

| Permanent air leak | 43 (20.4) | 8 (8.6) | 0.001 | 15 (22.7) | 8 (12.1) | 0.10 | |

| Length of surgery (min) | 91.11±24.43 | 86.38±18.265 | 0.10 | 99.02±27.1 | 86.74±16.85 | 0.003 | |

| Length of drainage (days) | 4.63±4.58 | 3.39±3.39 | 0.02 | 5.12±4.77 | 3.83±3.81 | 0.02 | |

| Drain reinsertion | 14 (6.6) | 2 (2.7) | 0.10 | 5 (7.57) | 2 (3.0) | 0.44 | |

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or number (percentage). *, due to the small element number, statistical analysis was omitted. GA-VATS, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under general anesthesia; SVI-VATS, spontaneous ventilation with intubation video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Discussion

The synergistic effect of surgical and anesthesiologic trauma on the lung parenchyma during resection challenges both surgeons and anesthetists to reduce the mechanical harm caused. The basic question for the present study was the minimum invasiveness of anesthesia that does not compromise surgical principles and technical capabilities.

In highly selected cases, NITS offers a viable and minimally invasive surgery-anesthesia option. SVI-VATS, spontaneous ventilation thoracic surgery combined with double-lumen tube intubation, offers a solution to fulfill the expectations of both actors. Theoretically to secure a safe airway, an alternative solution could be the use of single-lumen tube intubation with a bronchial blocker in selected cases. After several years of experience with the NITS technique, we decided to provide evidence for the safety of SVI surgery in the field of thoracic surgery. SVI-VATS provides the advantage of a safe airway without compromising surgical accuracy (13). This study investigated the feasibility of using SVI in everyday practice.

Analysis of the characteristics of the GA-VATS and SVI-VATS groups showed no extended differences between the groups, except for the BMI, which was one of the most important selection factors in both groups (BMI less than 30 kg/m2). Generally, BMI is not an exclusion criterion in GA-VATS lobectomy, but it is an important selection factor in spontaneous ventilation surgery. This is because a higher BMI can cause more diaphragm movement, which can require conversion into the relaxed method. Because a BMI less than 30 kg/m2 was the criterion to select the patients into the SVI-VATS group, we accepted this selection into the GA-VATS group as well.

The site of the lung lesion and stage of NSCLC did not affect the choice of surgery. SVI-VATS was also used for the higher stages. After processing the patients’ data, we found that the left lower lobe (P=0.001) was operated on more frequently using the GA-VATS technique and the right lower lobe using SVI-VATS (P=0.001). This was only a coincidence, and this phenomenon may have little influence on the final result because the technical performance was the same for lower lobectomies on both sides.

In the case of spontaneous ventilation thoracic surgery, such as NITS and SVI, the lack of high intraalveolar pressure reduces the inevitable oxidative stress, alveolar damage, and other well-known (14-16) side effects of mOLV and GA (muscle relaxants, post-operative nausea-vomitus). In our study, during the immediate postoperative course, the lower incidence of serious complications in the SVI-VATS group supports our primary hypothesis that the effect of double-lumen intubation using spontaneous ventilation during thoracic surgery keeps the lung integrity and the defense mechanism of the body closer to normal function. Grade IIIb or higher complications (regarding the Clavien-Dindo classification) (P=0.01), reoperation rate (P=0.02), persistent air leak (P=0.001), and length of thoracic drain (P=0.02) were significantly lower in the SVI-VATS group.

It is very important to ensure that oncological principles are upheld during SVI-VATS. The number of removed mediastinal lymph nodes and the stages of lung cancers were either the same or very similar in the different groups.

After propensity score matching analysis, the length of surgery and the length of the thoracic drain were found to be statistically significant in terms of the analyzed parameters. The shorter surgical time in the SVI-VATS group primarily demonstrates the efficacy of the procedure and the technical similarities between the two procedures. One possible explanation for the reduction in surgery length is that atelectasis is better in cases of spontaneous ventilation, making it easier to explore the anatomy. The superior atelectasis during SVI-VATS surgery may also contribute to the shorter drainage time and lower incidence of recurrent pneumothorax, as better atelectasis leads to better stapler function. In our practice with non-intubated VATS lobectomy, we have observed that atelectasis is more complete compared to intubated cases. Although the underlying reasons are not fully detailed in the literature, we believe that the air outflow from the independent lung is more efficient. In some cases, the macroscopic view of the lung during the non-intubated cases resembles that of the liver. In SVI, atelectasis is intermediate between the non-intubated and GA cases; however, it is generally more complete than in GA surgery, likely owing to the movement of the dependent lung and mediastinum during spontaneous ventilation. In this more atelectatic lung, the efficacy of the stapler is enhanced, resulting in less air leakage. Furthermore, in SVI cases, anesthesia enables controlled ventilation of the independent lung at any time and with any desired volume, which helps manage air leaks from the parenchyma or anastomosis in cases of sleeve resection. Considering the heterogeneous patient population, the prospective data collection, and the efficacy of the propensity score matching analysis, our study’s findings are strongly supported.

However, this study has several limitations. The data were collected from a single institution with an experienced surgical-anesthesiologic team, a dedicated thoracic surgeon, and a long history of cooperation. The two different periods of the SVI-VATS and GA-VATS procedures can significantly affect the technical knowledge of the surgeon and the final outcomes. Patient selection was not randomized prior to entering the study, resulting in a highly representative patient population and prospective data entry. Furthermore, the comparison between the two techniques further reduced the sample size. During the propensity score matching analysis, tumor size or stage was not taken into account, even though these factors can affect the complexity of the surgical procedure.

Conclusions

The perioperative data from SVI-VATS lung lobectomies indicate that spontaneous ventilation thoracic surgery has a positive impact on the perioperative period. Fewer complications and a particularly lower rate of air leak-related morbidity were found following SVI-VATS lobectomies. Notably, the incidence of grade IIIb complications was significantly low following SVI-VATS lobectomies (Figure 1).

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the TREND reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1396/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1396/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1396/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1396/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Human Investigation Review Board of the University of Szeged (No. 4703/2020.01.20), and informed consent was taken from all the patients.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Molnar TF. Tuberculosis: mother of thoracic surgery then and now, past and prospectives: a review. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:S2628-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Molnar TF. History of thoracic surgery. In: Kuzdzal J, editor. ESTS textbook of thoracic surgery; Vol. 1. Cracow, Poland: Medycyna Praktyczna; 2014. p. 3-33.

- Rocco G. Operative VATS: the need for a different intrathoracic approach. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2005;28:358-author reply 358-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Batchelor TJP, Rasburn NJ, Abdelnour-Berchtold E, et al. Guidelines for enhanced recovery after lung surgery: recommendations of the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society and the European Society of Thoracic Surgeons (ESTS). Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2019;55:91-115. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Katira BH, Giesinger RE, Engelberts D, et al. Adverse Heart-Lung Interactions in Ventilator-induced Lung Injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2017;196:1411-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lantos J, Németh T, Barta Z, et al. Pathophysiological Advantages of Spontaneous Ventilation. Front Surg 2022;9:822560. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chiang XH, Lin MW. Converting to Intubation During Non-intubated Thoracic Surgery: Incidence, Indication, Technique, and Prevention. Front Surg 2021;8:769850. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Furák J, Szabó Z. Spontaneous ventilation combined with double-lumen tube intubation in thoracic surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021;69:976-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yan TD, Cao C, D'Amico TA, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery lobectomy at 20 years: a consensus statement. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014;45:633-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rami-Porta R, Bolejack V, Giroux DJ, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: the new database to inform the eighth edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2014;9:1618-24.

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-13. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Szabo Z, Fabo C, Szarvas M, et al. Spontaneous Ventilation Combined with Double-Lumen Tube Intubation during Thoracic Surgery: A New Anesthesiologic Method Based on 141 Cases over Three Years. J Clin Med 2023;12:6457. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Furák J, Barta Z, Lantos J, et al. Better intraoperative cardiopulmonary stability and similar postoperative results of spontaneous ventilation combined with intubation than non-intubated thoracic surgery. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2022;70:559-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Leaver HA, Craig SR, Yap PL, et al. Lymphocyte responses following open and minimally invasive thoracic surgery. Eur J Clin Invest 2000;30:230-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dongel I, Gokmen AA, Gonen I, et al. Pentraxin-3 and inflammatory biomarkers related to posterolateral thoracotomy in Thoracic Surgery. Pak J Med Sci 2019;35:464-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Furák J, Németh T, Lantos J, et al. Perioperative Systemic Inflammation in Lung Cancer Surgery. Front Surg 2022;9:883322. [Crossref] [PubMed]