Diagnostic utility of endobronchial ultrasound elastography for detecting benign and malignant lymph nodes: a retrospective study

Highlight box

Key findings

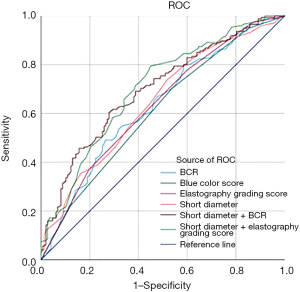

• The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for the combined index of elastography grading score and short diameter was 0.702. The blue color ratio (BCR) could be employed in the detection of benign and malignant lymph nodes; however, BCR was unable to differentiate between lymph nodes with benign and small cell carcinoma.

What is known and what is new?

• Prior research highlights the diagnostic value of the semi-quantitative elastography index (BCR) for distinguishing between benign and malignant lymph nodes.

• Our study exhibits that BCR was affected by the pathology and location of lymph nodes.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• It is recommended that invasive endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration remains the preferred option.

• Further research is essential to explore the factors affecting the BCR.

Introduction

Lung cancer appears to be one of the main causes of cancer-related death globally, even with the development of multimodal treatment (1,2). With the objective to enhance survival time, lung cancer detection and staging are crucial. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) has approved endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) as the initial diagnostic technique for staging lung cancer in the lymph nodes. This minimally invasive and safe procedure has been shown to be productive (3). According to a meta-analysis, EBUS-TBNA had a 90% and 99% sensitivity and specificity for mediastinal staging (4). In order to improve the diagnostic effectiveness of EBUS-TBNA, investigators are investigating diverse technical optimization techniques.

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) elastography is an imaging technique, which can predict lymph node benignity or malignancy by the stiffness of lymph nodes with different colors (5-8). In the qualitative elastography study, the sensitivity and specificity of the image classification method—designating ‘green-dominant’ as benign and ‘blue-dominant’ as malignant—ranged from 71% to 100% and 65% to 92.3%, respectively. However, this classification was deemed overly subjective for evaluating lymph nodes exhibiting a mix of blue and green coloration, which ultimately led to its rejection (5,9-13). In 2015, He and her colleagues utilized an elastography grading score, establishing a threshold value of 2.5, whereby scores of 1–2 were classified as benign and scores of 3–4 were classified as malignant (14). In the context of semi-quantitative elastography indices, blue color ratio (BCR) have demonstrated a stronger predictive relevance for differentiating between benign and malignant lymph nodes (15-18). However, the optimal and standard evaluation method remains unidentified, and the accuracy of elastography is yet to be thoroughly investigated.

In this study, we attempted to assess the diagnostic usefulness of EBUS elastography for detecting benign and malignant lymph nodes, as well as the factors that influence this process. We present this article in accordance with the STARD reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1042/rc).

Methods

Patient enrollment

We conducted a single-center, retrospective study enrolling patients with suspected lung cancer who received EBUS elastography followed by EBUS-TBNA at Zhejiang Cancer Hospital from October 2021 to March 2023. The inclusion criteria for patients were as follows: (I) with suspected lung cancer and enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes: at least one mediastinal lymph node short axis diameter ≥1.0 cm on thoracic computed tomography (CT) scan and/or positron emission tomography (PET) scan; (II) receiving EBUS elastography and EBUS-TBNA; (III) aged 18–85 years. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (I) having previously received antitumor treatments such as chemotherapy, targeting and immunotherapy; (II) lacking confirmed diagnostic result. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (No. IRB-2023-569). The requirement for individual consent for this retrospective study was waived.

Procedure description

An experienced interventional pulmonary physician performed all the procedures in this retrospective analysis. All patients were ventilated with a laryngeal mask under general intravenous anesthesia and underwent EBUS-TBNA. The convex probe (BF-UC260FW, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted through a three-way connecting tube and used to locate the lymph nodes for selective sampling based on node dimensions on CT scan and morphology at ultrasound, and vascular pattern. The largest diameter of the lymph node could be seen in the center of the ultrasound image by progressively moving and adjusting the EBUS scope. After switching to elastography mode, a stable image was obtained, frozen and also saved in JPG format for further analysis. A 22-gauge Olympus fine needle was advanced along the puncture route once the target lymph nodes were identified. Each target lymph node was punctured three to four times. A positive finding in either the histological or cytological examination supported the diagnosis. Benign disease was verified by follow-up six months post-EBUS-TBNA.

Data collection and image analysis

The demographic and clinical data of the patients were collected and recorded, including age, body mass index (BMI), sex, smoking history, types of disease, pathology and station of lymph nodes. The size and location of the lymph nodes were noted in conventional ultrasonography mode. The short axis diameter was noted. And according to the latest lymph node staging guidelines (19), lymph nodes were be divided into mediastinal lymph nodes (2R, 4R, 4L, 7) and hilar lymph nodes (10R, 10L, 11R, 11L, 12R/L).

The characteristics of lymph node elastography were evaluated and recorded with some modifications as follows: (I) elastography grading score was determined using a semi-quantitative 4-point scale for lymph node elastography, based on the previous study (19). One point when red or green section was over 80%; two points when green and yellow/red section was over 50% but no more than 80%; three points when blue section was over 50% but less than 80%; and four points when blue section was over 80%. (II) The BCR was calculated by Image J software, version1.6.0. The ratio of blue region to the entire lesion area pixel points was determined as previous study (20). The image of the targeted lymph node was cut to calculate the pixels of the whole lymph node area. Next, the hue value was adjusted to 145–180 (blue) and the brightness value was adjusted to 0–255 to calculate the pixels of the relatively stiffer tissue section (blue section). (III) Blue color score: The BCR served as the basis for the 4-point scoring system. Situations with a blue region area percentage of between 0% and 20% received one point, and situations with a percentage of between 20% and 50% received two points. Those with blue region area percentages between 50% and 80% received three points, and those with blue region area percentages between 80% and 100% received four points.

Statistical analysis

Non-normally distributed quantitative data were expressed as the median. The Mann-Whitney U-test was employed for the purpose of comparing two groups, while the Kruskal-Wallis test was used for the comparison of more than two groups. Categorical data were presented as frequencies and percentages and were compared using the Chi-squared test. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify independent risk factors for elastography, lymph node benignity and malignancy. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was performed to assess the diagnostic performance of elastography indices. The optimal cut-off value was determined as the optimal diagnostic threshold using the Youden index. Data processing and analysis were performed using R version 4.4.0 (2024-04-24), along with Zstats 1.0 (www.zstats.net) and software SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences were considered statistically significant when P value less than 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of the patients and lymph nodes

As shown in Table 1, a total of 168 patients of suspected lung cancer were included in this study, with a median age of 64 years (range, 28–81 years). Among the 168 individuals, 107 (63.7%) had primary lung cancer, and 61 (36.3%) had benign conditions. There were 322 lymph nodes punctured in Table 2; each patient had an average of 1.92 lymph node stations punctured. Based on EBUS-TBNA pathology, 175 (54.3%) were malignant, 147 (45.6%) were benign. And lymph nodes were staged were recorded in Table 2.

Table 1

| Patient characteristics | Values (N=168) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median | 64 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median | 23.1 |

| Male, n (%) | 102 (60.7) |

| Smoking history, n (%) | |

| Non-smoking | 83 (49.4) |

| Smoking | 85 (50.6) |

| Underlying disease, n (%) | |

| Malignancy | 107 (63.7) |

| Primary lung cancer | 107 (63.7) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 49 (29.2) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 26 (15.5) |

| Non-small cell carcinoma | 12 (7.1) |

| Small cell carcinoma | 20 (11.9) |

| Benign process | 61 (36.3) |

| Sarcoidosis | 13 (7.7) |

| Tuberculosis | 8 (4.8) |

| Benign lung tumor | 17 (10.1) |

| Reactive lymphoid hyperplasia | 7 (4.2) |

| Pneumonic mass | 15 (8.9) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (0.6) |

BMI, body mass index.

Table 2

| LNs characteristics | Number of lymph nodes (N=322) |

|---|---|

| Short diameter (mm), median | 14.0 |

| Pathology, n (%) | |

| Malignant | 175 (54.3) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 58 (18.0) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 23 (7.1) |

| Non-small cell carcinoma | 22 (6.8) |

| Small cell carcinoma | 29 (9.0) |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 43 (13.4) |

| Benign | 147 (45.6) |

| Tuberculosis (caseous necrosis) | 3 (0.9) |

| Granuloma | 27 (8.4) |

| Unspecific | 117 (36.3) |

| Location, n (%) | |

| 2R | 7 (2.2) |

| 4R | 96 (29.8) |

| 4L | 23 (7.1) |

| 7 | 95 (29.5) |

| 10R | 4 (1.2) |

| 10L | 1 (0.3) |

| 11R | 54 (16.8) |

| 11L | 38 (11.8) |

| 12R | 3 (0.9) |

| 12L | 1 (0.3) |

| Position, n (%) | |

| Hilar | 101 (31.4) |

| Mediastinal | 221 (68.6) |

LNs, lymph nodes.

The diagnostic value of elastography indices in the differentiation between benign and malignant lymph nodes

Among the 322 lymph nodes, Table 3 summarizes the serological markers and elastography indices in the differentiation of benign and malignant mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Among them, lactated hydrogenase (LDH, P<0.001), squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCCA, P=0.008), cytokeratin-19-fragment (CYFRA21-1, P<0.001), neuron specific enolase (NSE, P<0.001), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA, P=0.001) and pro-gastrin-releasing peptide (Pro-GRP, P=0.04) were significant to discern the distinctions between benign and malignant lymph nodes. Multivariate regression analysis demonstrated that elastography grading score and short axis diameter were significant factors (Table 4). When the optimal threshold value was 2.5, the sensitivity and specificity of the elastography grading score were 77.7% and 40.1%, respectively. The optimal cut-off value of BCR for distinguishing benign from malignant lymph nodes was determined to be 66.5% with the sensitivity and specificity of 49.1% and 73.5%, respectively. The combined index of elastography and lymph node short diameter exhibited the highest diagnostic value, with an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.702 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.645–0.759] in Figure 1.

Table 3

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| LDH (U/L) | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | <0.001*** | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.55 | |

| CRP (mg/L) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.85 | |||

| CYFRA21-1 (ng/mL) | 2.92 (2.20–3.86) | <0.001*** | 2.38 (1.66–3.42) | <0.001*** | |

| SCCA (ng/mL) | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | 0.008** | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) | 0.009** | |

| NSE (ng/mL) | 2.06 (1.66–2.56) | <0.001*** | 1.51 (1.20–1.89) | <0.001*** | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.07 (1.33–3.22) | 0.001** | 1.21 (0.58–2.53) | 0.61 | |

| Pro-GRP (pg/mL) | 1.01 (1.01–1.01) | 0.04* | 1.00 (1.00–1.01) | 0.13 | |

| BCR (%) | 7.65 (2.87–20.39) | <0.001*** | 0.73 (0.03–16.32) | 0.84 | |

| Short diameter (mm) | 3.03 (1.84–5.00) | <0.001*** | 6.49 (2.33–18.09) | <0.001*** | |

| Elastography grading score | |||||

| 1 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| 2 | 3.49 (1.18–10.29) | 0.02* | 6.06 (0.79–46.21) | 0.08 | |

| 3 | 4.81 (1.70–13.61) | 0.003** | 6.86 (0.72–65.42) | 0.09 | |

| 4 | 8.97 (3.07–26.22) | <0.001*** | 21.33 (1.37–333.22) | 0.03* | |

| Position | |||||

| Hilar | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Mediastinal | 1.41 (0.88–2.26) | 0.16 | |||

*, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LDH, lactated hydrogenase; CRP, C-reactive protein; CYFRA21-1, cytokeratin-19-fragment; SCCA, squamous cell carcinoma antigen; NSE, neuron specific enolase; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; Pro-GRP, pro-gastrin-releasing peptide; BCR, blue color ratio.

Table 4

| Ultrasound parameters | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

ACC (%) |

AUC | P | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||||

| BCR (%) | ≥66.5 | 49.1 | 73.5 | 68.8 | 54.8 | 58.4 | 0.633 | <0.001*** | 0.573 | 0.694 |

| Blue color score | ≥2.5 | 70.3 | 46.3 | 60.9 | 56.7 | 57.5 | 0.610 | 0.001** | 0.548 | 0.672 |

| Elastography grading score | ≥2.5 | 77.7 | 40.1 | 60.7 | 60.2 | 58.7 | 0.633 | <0.001*** | 0.572 | 0.694 |

| Short axis diameter (mm) | ≥12.5 | 73.7 | 48.3 | 62.9 | 60.7 | 60.2 | 0.645 | <0.001*** | 0.585 | 0.705 |

| BCR + short diameter | – | 60.6 | 72.1 | – | – | – | 0.698 | <0.001*** | 0.641 | 0.755 |

| Elastography grading score + short diameter | – | 79.4 | 55.1 | – | – | – | 0.702 | <0.001*** | 0.645 | 0.759 |

**, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. BCR, blue color ratio; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; ACC, accuracy; AUC, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; CI, confidence interval.

Analysis of factors influencing elastography indices

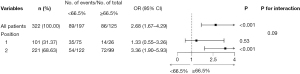

The pathological type and location of lymph nodes were factors that influenced the percentage of the blue area observed on elastography (Table 5). Elastography was effective in differentiating between lymph nodes affected by benign conditions and those with non-small cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. However, it was not able to distinguish between lymph nodes affected by benign conditions and those with small cell lung carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Figure 2 demonstrated that BCR (≥66.5%) could effectively identify malignant lymph nodes, particularly in the mediastinal region.

Table 5

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | ||

| LN pathology | |||||

| Benign | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 3.41 (1.81–6.42) | <0.001*** | 3.33 (1.75–6.33) | <0.001*** | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1.78 (0.71–4.44) | 0.22 | 1.74 (0.69–4.40) | 0.24 | |

| Non-small cell carcinoma | 4.00 (1.59–10.09) | 0.003** | 4.06 (1.58–10.41) | 0.004** | |

| Small cell carcinoma | 1.25 (0.52–2.97) | 0.62 | 1.28 (0.53–3.08) | 0.59 | |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 3.18 (1.58–6.43) | 0.001** | 2.89 (1.42–5.88) | 0.004** | |

| Position | |||||

| Hilar | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| Mediastinal | 2.34 (1.39–3.93) | 0.001** | 2.20 (1.29–3.78) | 0.004** | |

**, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. BCR, blue color ratio; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; LN, lymph node.

Discussion

In this study, the elastography grading score (4-point scale), the blue color score (4-point scale) and the BCR were selected as semi-quantitative evaluation parameters. The diagnostic utility of the elasticity indices for the detection of malignancy in mediastinal lymph nodes was found to be limited. The combination of lymph node short axis diameter with the elasticity indices demonstrated moderate diagnostic value.

The elastography grading score was 85.7%, 76.9%, and 82.3% in terms of accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity in previous study (14). The BCR index had a diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of 81% to 88.2% and 80.2% to 85%, respectively (15-18). The specificity of the elastography grading score in this study was found to be inferior to that observed in previous studies, while the sensitivity of the BCR was also less than that reported in previous research.

The BCR cut-off value for benign and malignant lymph nodes in our study was 66.5%, which is higher in comparison with previous researches (31.1% or 60.0%) (16,20). It was considered that the high BCR cut-off value in our study was due to the sample selection, since 107 (63.7%) of the participants had malignant tumors. In our data set, 89 lymph nodes (89/197, 45.2%) exhibited BCR values below 66.5% on elasticity images, despite the presence of metastases. These tumors are postulated to be highly aggressive, akin to small-cell lung cancers in this study. They are nevertheless capable of spreading even in the lack of significant colonization. However, it can also suggest that the blue regions seen on lymph node elastography were actual metastasis-containing regions. The elastography-provided blue region distribution map could make it easier for EBUS-TBNA to obtain more significant diseased tissue (15,16,21,22). Thirty-nine lymph nodes (39/125, 31.2%) had BCR values over 66.5% on the elastography; yet, the results of the EBUS-TBNA puncture were negative. It is crucial to take into account the potential for misleading negative results in patients with lung cancer. To ascertain the tumor staging and available treatments, more clarification regarding the type of lymph nodes is needed in addition to the data from PET, re-puncture, or discussions at a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting. It is important to identify fibrosis and necrosis inside the lymph nodes in patients with benign illness.

Wang et al. (20) showed that lymph node station had no effect on BCR. However, our research showed a tendency for higher BCR in mediastinal lymph nodes compared to hilar lymph nodes. It is necessary to look into the affecting elements more thoroughly. And this study was constrained by its single-center setup, retrospective design. In this study, the collected data revealed a significant proportion of patients with malignant diseases, particularly those at advanced stages of lung cancer. Consequently, lymph node stiffness may be elevated, even in the absence of positive pathology in the punctured lymph nodes. In patients with benign conditions, factors such as benign tumors and tuberculosis can also contribute to increased lymph node stiffness. Further research is needed to investigate the factors influencing the elasticity indices and to improve the diagnostic utility.

Conclusions

The use of elastography data alone may be insufficient for the diagnosis of metastatic lymph nodes. However, when combined with the short axis diameter of lymph nodes, elastography indices offer moderate diagnostic value for detecting lung cancer metastases in the mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. In the context of EBUS-TBNA, elastography may provide supplementary diagnostic information for identifying metastatic lymph nodes in conjunction with pathological, radiological, and clinical findings.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STARD reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1042/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1042/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1042/prf

Funding: This study was supported by grants from

Conflicts of Interest: Both authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1042/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (No. IRB-2023-569). Informed consent was waived given the retrospective nature of the study.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Bade BC, Dela Cruz CS. Lung Cancer 2020: Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention. Clin Chest Med 2020;41:1-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Qi J, Li M, Wang L, et al. National and subnational trends in cancer burden in China, 2005-20: an analysis of national mortality surveillance data. Lancet Public Health 2023;8:e943-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Silvestri GA, Gonzalez AV, Jantz MA, et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2013;143:e211S-50S.

- Murgu SD. Diagnosing and staging lung cancer involving the mediastinum. Chest 2015;147:1401-12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Izumo T, Sasada S, Chavez C, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound elastography in the diagnosis of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2014;44:956-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Korrungruang P, Boonsarngsuk V. Diagnostic value of endobronchial ultrasound elastography for the differentiation of benign and malignant intrathoracic lymph nodes. Respirology 2017;22:972-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rozman A, Malovrh MM, Adamic K, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound elastography strain ratio for mediastinal lymph node diagnosis. Radiol Oncol 2015;49:334-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Andreo García F, Centeno Clemente CÁ, Sanz Santos J, et al. Initial experience with real-time elastography using an ultrasound bronchoscope for the evaluation of mediastinal lymph nodes. Arch Bronconeumol 2015;51:e8-e11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin CK, Yu KL, Chang LY, et al. Differentiating malignant and benign lymph nodes using endobronchial ultrasound elastography. J Formos Med Assoc 2019;118:436-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang H, Huang Z, Wang Q, et al. Effectiveness of the Benign and Malignant Diagnosis of Mediastinal and Hilar Lymph Nodes by Endobronchial Ultrasound Elastography. J Cancer 2017;8:1843-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gompelmann D, Kontogianni K, Sarmand N, et al. Endobronchial Ultrasound Elastography for Differentiating Benign and Malignant Lymph Nodes. Respiration 2020;99:779-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gu Y, Shi H, Su C, et al. The role of endobronchial ultrasound elastography in the diagnosis of mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Oncotarget 2017;8:89194-202. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fournier C, Dhalluin X, Wallyn F, et al. Performance of Endobronchial Ultrasound Elastography in the Differentiation of Malignant and Benign Mediastinal Lymph Nodes: Results in Real-life Practice. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2019;26:193-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- He HY, Huang M, Zhu J, et al. Endobronchial Ultrasound Elastography for Diagnosing Mediastinal and Hilar Lymph Nodes. Chin Med J (Engl) 2015;128:2720-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakajima T, Inage T, Sata Y, et al. Elastography for Predicting and Localizing Nodal Metastases during Endobronchial Ultrasound. Respiration 2015;90:499-506. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma H, An Z, Xia P, et al. Semi-quantitative Analysis of EBUS Elastography as a Feasible Approach in Diagnosing Mediastinal and Hilar Lymph Nodes of Lung Cancer Patients. Sci Rep 2018;8:3571. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang Z, Bai J, Jiao G, et al. Quantitative evaluation of endobronchial ultrasound elastography in the diagnosis of benign and malignant mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Respir Med 2024;224:107566. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Uchimura K, Yamasaki K, Sasada S, et al. Quantitative analysis of endobronchial ultrasound elastography in computed tomography-negative mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes. Thorac Cancer 2020;11:2590-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rusch VW, Asamura H, Watanabe H, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: a proposal for a new international lymph node map in the forthcoming seventh edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:568-77.

- Wang Y, Zhao Z, Zhu M, et al. Diagnostic value of endobronchial ultrasound elastography in differentiating between benign and malignant hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes: a retrospective study. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2023;13:4648-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhi X, Sun X, Chen J, et al. Combination of (18)F-FDG PET/CT and convex probe endobronchial ultrasound elastography for intrathoracic malignant and benign lymph nodes prediction. Front Oncol 2022;12:908265. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shiina Y, Nakajima T, Suzuki H, et al. Localization of the Metastatic Site Within a Lymph Node Using Endobronchial Elastography. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019;31:312-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]