COVID-19 infection and pulmonary sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of morbidity, severity and mortality

Highlight box

Key findings

• Sarcoidosis patients are prone to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, increased severity, morbidity and greater mortality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

What is known and what is new?

• Subjects with sarcoidosis are more vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

• Severity of COVID-19 was also more serious in subjects stricken with sarcoidosis.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 for sarcoidosis may be a compulsory measure.

Introduction

On late 2019, several cases of an acute, severe, highly transmissible respiratory disease were first reported in Wuhan, China (1). Evolved as a worldwide pandemic, this disease was explained as a viral illness caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and later designated as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Spreading globally, COVID-19 has reported over 767 million confirmatory cases and over 6.9 million deaths (2). Symptoms such as coughing, fever, dyspnea, and sore throat were commonly noted, and pneumonia, sepsis, and respiratory failure was also seen on severe occasions. COVID-19 endangered millions of subjects: not only individuals with no apparent underlying disease were threatened by this pandemic disease, but also the health of people with comorbidities involving various organs was at a much serious risk.

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a collection of inflammatory and/or fibrotic pulmonary disorders with substantial morbidity and mortality. Subjects with pre-existing ILDs are at a high risk of lung complications from COVID-19 (3-5). ILD patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 are prone to poor outcomes predominantly requiring hospitalization. Of those, sarcoidosis is a systemic disorder with granulomatous inflammation due to unknown origin among the heterogeneous constellation of ILD. Sarcoidosis is an illness virtually involving the entire part of body. Major involvement of organs in sarcoidosis patients is the lung, with more than 90% of subjects having lung or intra-thoracic lymph node involvement. This involvement on lung leads to a damage on lung tissue distorting pulmonary architecture followed by extensive fibrosis (6). Regimens adopted for disease control on sarcoidosis patients may accompany opportunistic infection, and remedies utilized for sarcoidosis have an immunosuppressive effect [e.g., glucocorticosteroids, azathioprine, methotrexate, anti tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha inhibitors, etc.]. This raises concerns on microbial or viral attack unless immunized, and several infection vaccinations are proposed for sarcoidosis, including influenza, herpes, pneumococcus, and so on (7). Preventive, proactive actions are therefore justified for sarcoidosis against viral infection including SARS-CoV-2 caused by COVID-19.

According to previous studies, sarcoidosis patients are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, but severe outcomes such as intensive care unit (ICU) admission or even death were lower than anticipated (8,9). On the other hand, some similarity in the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and sarcoidosis is discussed by several researchers such as Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway or cytokine hypersecretion (or storm), leading to an argument that risk of severe COVID-19 event in sarcoidosis patients will be increased (10). Other concepts and hypotheses emerged, such as disruption of C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) signaling to treat the cytokine storm with a human monoclonal antibody leronlimab (11), roles of sonic hedgehog and Wnt5a pathways on COVID-19-related pneumomediastinum (12), or several cytokines as potential markers regarding COVID-19 induced acute distress respiratory syndrome (ARDS) (13). However, there has been scarce data or scientific evidence regarding our hypothesis, that sarcoidosis patients are prone to SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with other ILDs and the death rate is lower than that of other ILDs.

In this meta-analytic study, we evaluated our proposition that COVID-19 is more common in sarcoidosis alike other ILDs, and on the other hand that the severity of COVID-19 (e.g., ICU admission and death) is less serious than suggested. We present this article in accordance with the PRISMA reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1620/rc).

Methods

This investigation is a meta-analysis utilizing previously studied and published reports, therefore pre-study review by the institutional review board is not required.

Literature search

A comprehensive search of several databases including Medline, Cochrane Library, Embase, Web of Science and KoreaMed was conducted. The search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced librarian with input from study investigators. The search strategy and terms are presented in Table S1.

Three investigators (W.J.J., S.I.C., and E.J.L.) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all retrieved studies to exclude irrelevant studies. If there was disagreement on exclusion, discordant studies were included in the next stage of the full-text review. Full-text reviews of all included studies from the first step were independently performed by three investigators (W.J.J., S.I.C., and E.J.L.). Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the three reviewers. The bibliography of included studies and previous reviews were also reviewed manually to identify additional studies.

Quality assessment

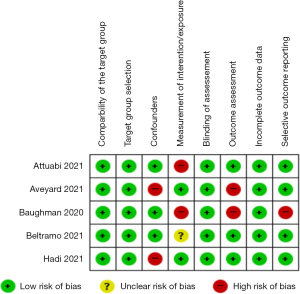

Risk of bias assessment was evaluated using Risk of Bias Assessment tool for Non-randomized Study 2 (RoBANS 2). Two investigators (E.J.L. and S.P.) evaluated independently the risk of bias for each study. RoBANS 2 is consisted of eight domains, and the risk of bias of each domain are classified as low, unclear, or high (14).

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was conducted to assess the effect of COVID-19 on sarcoidosis patients, using both fixed-effect and random-effects models. A multivariate fixed-effect and random-effects model was applied to combine the results from different studies, with a frequentist framework for the random-effects model used to analyze the incidence of COVID-19. The common-effect model was used for analyzing ICU admission and mortality outcomes, assuming that the studies assessed a similar effect size for these outcomes. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were considered summary estimates of treatment response effect sizes for the COVID-19 incidence on sarcoidosis patients. To assess the presence of heterogeneity among the studies, the I2 statistic was used. This statistic quantifies the proportion of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than chance, and values closer to 100% indicate substantial variability among study results. All statistical analyses were performed using R software (Version 4.3.1, ‘meta’ and ‘metafor’ packages; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), utilizing the ‘meta’ and ‘metafor’ packages for conducting meta-analyses and assessing heterogeneity, respectively. The I2 statistic and other meta-analysis procedures were computed to assess the robustness and consistency of the overall effect sizes.

Results

Flow chart of study selection

Database searching Medline, Embase, Cochrane, Web of Science, and KoreaMED resulted in 1,047 articles in total. Of those, 388 duplicate reports were removed and subsequent record screening ensued. Twenty studies were chosen from that process, and eligibility was evaluated by reviewing the full-text articles. Several reasons were noted from the studies, such as less than 20 cases of COVID-19-positive sarcoidosis patients (n=7), some reports without general population as a control group (n=2), or ineligible participants in the study (n=6) and excluded. Overall, five investigational reports were finally selected for meta-analysis as follows (Figure 1).

Quality assessment of our study

Five studies were evaluated for quality assessment using RoBANS 2. Figure 2 illustrates the result of RoBANS 2 of each domain for the investigational reports adopted for meta-analysis.

Incidence of COVID-19 on sarcoidosis patients

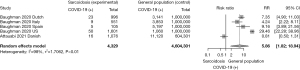

Two studies were utilized for analysis of COVID-19 incidence in sarcoidosis patients, and these reports revealed to have an opposite result. A total of 4,329 sarcoidosis cases and 4,604,301 control subjects were involved in the analysis. A study from Denmark (15) reported a weak propensity of SARS-CoV-2 infection in sarcoidosis patients compared with the general population, with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.50–1.31). In contrast, the study by Baughman et al. (16) with sarcoidosis patients from four countries (the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, and the United States) revealed a strong, statistically significant RR toward COVID-19 incidence, ranging from 4.24 to 29.46 in values. The RR of COVID-19 incidence on sarcoidosis patients was 5.86 (95% CI: 8.02–11.91). The analysis (utilizing two studies with opposite results) showed a significant heterogeneity (I2=98%) (Figure 3).

ICU admissions of COVID-19 sarcoidosis patients

A total of 18,176 sarcoidosis cases and 8,605,246 control subjects were involved in the analysis. Figure 4A exemplifies the possibility of ICU admission of sarcoidosis patients after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Three studies—Aveyard et al. (17), Beltramo et al. (18), and Hadi et al. (8)—were adopted for analysis, and the OR was 2.48 (95% CI: 2.04–3.01). Heterogeneity was insignificant (i.e., I2=0%, τ2=0, P=0.74).

Death of COVID-19 sarcoidosis patients

Three articles were utilized for reasoning the tendency of death of sarcoidosis patients after COVID-19 attack. A total of 18,176 sarcoidosis patients and 8,605,246 control subjects were utilized for analysis. The OR was 1.95 (95% CI: 1.58–2.41), showing a strong propensity of death of sarcoidosis patients on SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with the healthy population (Figure 4B). Heterogeneity among studies were weak (i.e., I2=60%, τ2=0.0543, P=0.08).

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, we confirmed that subjects ailed with sarcoidosis are more prone to SARS-CoV-2 infection, and that the severity of ensuing COVID-19 is significant than initially assumed. The incidence of COVID-19 was significantly higher than that of healthy subjects, in accordance with the previous study results and with our hypothesis. Contradictory to the initial assumption we made based upon previous studies (8,9), however, the severity of COVID-19 in sarcoidosis patients was more serious than that of the general population. This meta-analytic conclusion leads us to the justification of vaccinating sarcoidosis patients against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our investigation shows stark difference to previous studies of varied results regarding incidence, severity and mortality; all of these clinical pictures consistently depict sarcoidosis with COVID-19 as a serious problem. Therefore, our result underlines the importance of clinical approach toward sarcoidosis in the era of endemic COVID-19, requiring a more careful, vigilant method of management. Future prospects such as different vaccination schedule of SARS-CoV-2 infection, tailored management for sarcoidosis patients with COVID-19, and so on, are still needed.

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of largely unknown origin. An inflammatory granulomatous lesion occurs virtually on any organ of human, most commonly including lung. An unknown antigen induces an inflammatory reaction, leading to granuloma formation and aberrant cytokine secretion in affected organs and tissues (7). Progressive pulmonary lesions are discovered in about 10% to 30% of sarcoidosis patients (6). Moreover, death of subjects with sarcoidosis are mainly due to pulmonary involvement, with more than 60% of deaths linked to lung problem (19,20).

Subjects troubled with sarcoidosis are susceptible to infection due to several reasons. Dysregulated immune response seen in sarcoidosis is discussed as one of the mechanisms. It is characterized by an excessive T helper cell lymphocyte response, excessively accumulating at granulomatous lesions (alongside with macrophages). In the periphery, in contrast, weaker immune response is seen, referred to as a ‘immune paradox’ (21). Structural disruption of lung parenchyma such as cavitation or bronchiectasis is also prone to infection. In addition, sarcoidosis patients are commonly managed with immunosuppressive agents, further leading to vulnerability to various infections. Theoretically, preventing intrusion of various bacteria, viruses, and any other pathogenic organisms is crucial and vaccination is known as an effective and safe method of preemptive measurement.

Our initial hypothesis based on anecdotal experience, alongside with literature search and analysis of a previously published studies (8,9) of managing COVID-19 on top of sarcoidosis patients, was as follows: although the incidence of COVID-19 may be higher than that of the general population without sarcoidosis, severity (i.e., ICU admission) and mortality caused by COVID-19 will not be as serious as the incidence. Previous studies showed mixed results and claims regarding the incidence of COVID-19 on subjects with sarcoidosis (8,9,12-15). Of those, some researchers explained their study outcome of a lower-than-expected incidence, that the sarcoidosis patients were anxious of SARS-CoV-19 infection, and therefore more obedient to lockdown recommendation (17).

In our study, we enlisted subjects admitted only to the ICU and not to the general ward. Institutional admission of COVID-19 patients was widely varied among countries during the pandemic. This inconsistency of coping with COVID-19 was inevitable, partly due to circumstance of each community/nation in terms of medical resources. Also, initial reaction against this unprecedented infection was not scientifically established yet due to lack of knowledge, and a number of admissions done as a quarantine measure rather than a detailed medical support were included. ICU admissions, in contrast, were naturally adopted for COVID-19 cases with severe condition. Death of sarcoidosis patients related to COVID-19, the foremost severe outcome, was of course included in our study and analyzed.

The report by Baughman et al. (16), one of the investigational reports we have analyzed, was a multinational study (including the United States, the Netherlands, Italy, and Spain) summarizing the COVID-19 incidence from subjects with sarcoidosis. For detailed analysis, we subdivided the study group according to the nationality. Although the four countries participated in this study were Western developed nations, each country is believed to have a unique healthcare environment in many aspects, such as political, economic, social, or ethnic circumstances regarding the management of an unprecedented pandemic. This difference among four countries leads to a rational inference that epidemiologic consequences of COVID-19 with sarcoidosis will be influenced. From our analysis, sarcoidosis patients from four nations unanimously showed propensity of increased incidence of COVID-19 compared with healthy control group.

The Danish study by Attauabi et al. (15), another study included in our meta-analysis, on its own, revealed insignificant difference of COVID-19 incidence between subjects with or without sarcoidosis as an underlying disease. In this investigation, as one of the immune-mediated inflammatory diseases (IMID), sarcoidosis patients overwhelmed with COVID-19 were enrolled and analyzed. Diagnostic confirmation via reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed. Authors of this study explained that the initial, highly selective laboratory testing was released for anyone “as a containment strategy”, in which “only symptomatic patients were tested” for COVID-19, thus revealing a possibility of erroneous enlisting. Authors of this investigational report changed the enrollment strategy from containment to “mitigation”, with widening the screening criteria. However, our meta-analytic result showed a statistically significant predominance of COVID-19 infection on sarcoidosis patients group compared with the general population without lung disease.

Intuitively, the novel pandemic COVID-19 by SARS-CoV-2 is regarded as a threat to sarcoidosis patients as both an increased susceptibility and enhanced propensity of poor prognosis compared to disease-free subjects. However, there have been counterarguments among researchers. One study utilizing a questionnaire to a total of 5,200 sarcoidosis patients revealed a higher rate of COVID-19 cases compared with healthy subjects, with an additional finding that in a specific subgroup (i.e., questionnaire respondents that are authors’ collection) diagnosis rate abated down to that of non-sarcoidosis subjects (16). This investigation, however, seems to have some drawbacks in terms of confirmation of COVID-19; the method of infection verification of authors’ examinees who were questionnaire participants was specifically diagnosed with viral culture, while the rest of the participants’ method of confirmation was not clearly explained (i.e., rapid antigen test vs. RT-PCR vs. culture). Viral culture has a possibility of showing an erroneous false-negative result, influencing the result and interpretation; low sensitivity is another possible drawback (22-24). Presumably, the diagnostic tool was not identical among the participants, and this discrepancy of diagnosis is worth considering in the interpretation of this study.

Some resemblance between the pathogenesis of COVID-19 and sarcoidosis is discussed by several researchers, leading to a suggestion that the risk of severe COVID-19 events in sarcoidosis patients will be increased, or otherwise decreased on the contrary (10). One of the cores of this discussion regarding the correlation between these two disease entities is the JAK/STAT pathway. JAK/STAT pathway is a molecular apparatus used by several cytokines for intracellular signaling. JAK/STAT has been adopted for explaining excessive inflammation on various IMIDs, acting as a central role in secretion and several interleukins (25). Representative IMIDs are rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthritis, Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, sarcoidosis, and so on. As for sarcoidosis, there has been no apparent treatment regimen or recommendations utilizing JAK/STAT inhibitors to date, only with episodic cases reported managing cutaneous sarcoidosis (26) or a multi-organ sarcoidosis (27) with a JAK/STAT inhibitor tofacitinib. Large-scale investigations are underway and will elucidate the therapeutic role of JAK/STAT inhibitors in sarcoidosis management (28).

COVID-19 patients are sometimes stressed with “cytokine storm”, a hyper-inflammatory systemic reaction represented as various actions of cytokines and inflammatory cells, inducing acute respiratory distress and even multiple organ dysfunction. Host response against SARS-CoV-2 infection includes a constellation of mediators that are targeted in IMIDs (29). Inhibiting this JAK/STAT pathway was suggested as the treatment of the COVID-19 hyperinflammation state. Currently, baricitinib, one of the JAK inhibitors, combined with low-dose dexamethasone is recommended by WHO for treatment for patients with severe or critical COVID-19 (30) and by the NIH for treatment of COVID-19 hospitalized patients requiring high-flow oxygen or noninvasive ventilation, or conventional oxygen but with significantly elevated inflammatory markers (31).

Another one plausible mechanism as a common background for two diseases is the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE). ACE in sarcoidosis has been brought up as a marker for diagnosis, staging, treatment response monitoring, and prognostic estimation for many years, with mixed results of clinical usefulness (32). Since the outbreak of SARS-CoV-1 infection on 2002, the ACE2 drew attention as functioning as an important role, some researchers studied the plasma ACE2 in COVID-19 patients proving a significant increase in severe COVID-19 (33). SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2 receptors, entering lung cells, and subsequently downregulates the receptors. ACE2 activity is therefore disrupted on SARS-CoV-2 binding, leading to upregulation of angiotensin II. This will lead to a constellation of pathogenic response with resultant severe COVID-19 (34). However, a randomized control, open-label study examined the utility of ACE inhibitor and angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) toward admitted patients with COVID-19, with a result that COVID-19 patients did not benefit from ACE inhibitor or ARB, or likely an even deleterious outcome (35). To date, ACE inhibitor or ARB seems not beneficial for SARS-CoV-2 infected subjects.

Conclusions

Subjects stricken with sarcoidosis are more prone to the recent pandemic SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the severity of COVID-19 on sarcoidosis patients is verified to be more serious than the general population. Therefore, our study supports the justification of immunizing sarcoidosis patients against SARS-CoV-19 in order to evade COVID-19 illness. Further studies are needed regarding tailored modification of vaccination schedules for ILD patients including sarcoidosis, modification of vaccine dosage, immunization strategy for variant SARS-CoV-2, and so on.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the PRISMA reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1620/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1620/prf

Funding: None.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1620/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement:

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020;382:727-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19. [updated 15 June 2023; cited 2024 January 8]. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---15-june-2023

- Lee H, Choi H, Yang B, et al. Interstitial lung disease increases susceptibility to and severity of COVID-19. Eur Respir J 2021;58:2004125. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Drake TM, Docherty AB, Harrison EM, et al. Outcome of Hospitalization for COVID-19 in Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease. An International Multicenter Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202:1656-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Esposito AJ, Menon AA, Ghosh AJ, et al. Increased Odds of Death for Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease and COVID-19: A Case-Control Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020;202:1710-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Belperio JA, Shaikh F, Abtin FG, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: A Review. JAMA 2022;327:856-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Syed H, Ascoli C, Linssen CF, et al. Infection prevention in sarcoidosis: proposal for vaccination and prophylactic therapy. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2020;37:87-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hadi YB, Lakhani DA, Naqvi SFZ, et al. Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis: A multicenter retrospective research network study. Respir Med 2021;187:106538. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen ES, Patterson KC. Considerations and clinical management of infections in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2023;29:525-31. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kahlmann V, Manansala M, Moor CC, et al. COVID-19 infection in patients with sarcoidosis: susceptibility and clinical outcomes. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2021;27:463-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agresti N, Lalezari JP, Amodeo PP, et al. Disruption of CCR5 signaling to treat COVID-19-associated cytokine storm: Case series of four critically ill patients treated with leronlimab. J Transl Autoimmun 2021;4:100083. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baratella E, Bussani R, Zanconati F, et al. Radiological-pathological signatures of patients with COVID-19-related pneumomediastinum: is there a role for the Sonic hedgehog and Wnt5a pathways? ERJ Open Res 2021;7:00346-2021. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Salton F, Confalonieri P, Campisciano G, et al. Cytokine Profiles as Potential Prognostic and Therapeutic Markers in SARS-CoV-2-Induced ARDS. J Clin Med 2022;11:2951. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Seo HJ, Kim SY, Lee YJ, et al. RoBANS 2: A Revised Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions. Korean J Fam Med 2023;44:249-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Attauabi M, Seidelin JB, Felding OK, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019, immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and immunosuppressive therapies - A Danish population-based cohort study. J Autoimmun 2021;118:102613. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baughman RP, Lower EE, Buchanan M, et al. Risk and outcome of COVID-19 infection in sarcoidosis patients: results of a self-reporting questionnaire. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 2020;37:e2020009. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aveyard P, Gao M, Lindson N, et al. Association between pre-existing respiratory disease and its treatment, and severe COVID-19: a population cohort study. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:909-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Beltramo G, Cottenet J, Mariet AS, et al. Chronic respiratory diseases are predictors of severe outcome in COVID-19 hospitalised patients: a nationwide study. Eur Respir J 2021;58:2004474. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang CT, Heurich AE, Sutton AL, et al. Mortality in sarcoidosis. A changing pattern of the causes of death. Eur J Respir Dis 1981;62:231-8.

- Baughman RP, Winget DB, Bowen EH, et al. Predicting respiratory failure in sarcoidosis patients. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1997;14:154-8.

- Tavana S, Argani H, Gholamin S, et al. Influenza vaccination in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis: efficacy and safety. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2012;6:136-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ford L, Lee C, Pray IW, et al. Epidemiologic Characteristics Associated With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Antigen-Based Test Results, Real-Time Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (rRT-PCR) Cycle Threshold Values, Subgenomic RNA, and Viral Culture Results From University Testing. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e1348-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gniazdowski V, Paul Morris C, Wohl S, et al. Repeated Coronavirus Disease 2019 Molecular Testing: Correlation of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Culture With Molecular Assays and Cycle Thresholds. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73:e860-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mathuria JP, Yadav R. Rajkumar. Laboratory diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 - A review of current methods. J Infect Public Health 2020;13:901-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rojas P, Sarmiento M. JAK/STAT Pathway Inhibition May Be a Promising Therapy for COVID-19-Related Hyperinflammation in Hematologic Patients. Acta Haematol 2021;144:314-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Damsky W, Thakral D, Emeagwali N, et al. Tofacitinib Treatment and Molecular Analysis of Cutaneous Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 2018;379:2540-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Damsky W, Young BD, Sloan B, et al. Treatment of Multiorgan Sarcoidosis With Tofacitinib. ACR Open Rheumatol 2020;2:106-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang A, Singh K, Ibrahim W, et al. The Promise of JAK Inhibitors for Treatment of Sarcoidosis and Other Inflammatory Disorders with Macrophage Activation: A Review of the Literature. Yale J Biol Med 2020;93:187-95.

- Schett G, Sticherling M, Neurath MF. COVID-19: risk for cytokine targeting in chronic inflammatory diseases? Nat Rev Immunol 2020;20:271-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal A, Hunt B, Stegemann M, et al. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19. BMJ 2020;370:m3379. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. Bethesda (MD): National Institutes of Health (US); 2023 [cited 2024 January 8].

- Ramos-Casals M, Retamozo S, Sisó-Almirall A, et al. Clinically-useful serum biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis of sarcoidosis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2019;15:391-405. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reindl-Schwaighofer R, Hödlmoser S, Eskandary F, et al. ACE2 Elevation in Severe COVID-19. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:1191-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vaduganathan M, Vardeny O, Michel T, et al. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors in Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1653-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Writing Committee for the REMAP-CAP Investigators. Effect of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitor and Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Initiation on Organ Support-Free Days in Patients Hospitalized With COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2023;329:1183-96. Erratum in: JAMA 2023;330:2398 Erratum in: JAMA 2024;332:937. [Crossref] [PubMed]