Perioperative dynamic changes of systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, and hypoxemia in patients with acute type-A aortic dissection: an observational case-control study

Highlight box

Key findings

• In this study, it was found that compared to controls, patients with acute type-A aortic dissection (ATAAD) had significantly higher preoperative white blood cell count, interleukin (IL)6, IL8, tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), diamine oxidase (DAO), intestinal fatty-acid-binding protein (iFABP), and peptidoglycan (PGN) but a lower PaO2/FiO2 ratio. In patients with ATAAD, postoperative IL6, IL8, TNFα, DAO, iFABP, and PGN were significantly increased compared to preoperative levels, while PaO2/FiO2 ratio was further decreased. Elevated level of succinate persisted from preoperation to the 12- and 24-hour postoperative time points. PGN, iFABP, succinate, and the lowest rectal temperature during cardiopulmonary bypass were identified as the risk factors for postoperative hypoxemia.

What is known and what is new?

• In previous studies, it was reported that systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, and hypoxemia developed significantly in patients with ATAAD.

• In this study, we investigated the dynamic changes in systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, hypoxemia, and succinate level in patients with ATAAD and their impact on postoperative hypoxemia.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Our findings suggest that systemic inflammatory responses, gut injury, and hypoxemia increasingly intensified from preoperation to postoperation following total aortic arch repair combined with frozen elephant trunk procedure under hypothermic circulatory arrest and antegrade cerebral perfusion in patients with ATAAD. Succinate might be implicated in the exacerbation of systemic inflammatory responses and hypoxemia. Our results might be helpful in optimizing the therapeutic strategies for the attenuation of ATAAD-related systemic inflammatory responses in terms of intestinal barrier function and the succinate pathway.

Introduction

Hypoxemia occurs in approximately 50% of patients with acute type-A aortic dissection (ATAAD) and can be life-threatening in severe cases (1-4). It is widely acknowledged that systemic inflammatory responses figure prominently in the pathogenesis of hypoxemia in this patient population (1,2,5-12). Recent studies have indicated that systemic inflammatory responses may also contribute to gut injury, which could be implicated in the pathogenesis of the hypoxemia associated with ATAAD (9,13). Furthermore, investigations conducted in murine models of ischemia-reperfusion gut injury have demonstrated the crucial involvement of gut microbiota and gut microbe-derived succinate in the development of hypoxemia (14-17). However, the dynamic changes of systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, hypoxemia, and succinate levels in the blood of patients with ATAAD during the perioperative period remain unclear. In this study, we investigated the perioperative dynamic changes in systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, hypoxemia, and succinate levels in patients with ATAAD and their association with perioperative hypoxemia. We present this article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-141/rc).

Methods

Design and participants

We conducted a single-center, observational, case-control study which enrolled 24 patients with ATAAD admitted to Beijing Anzhen Hospital between June 2022 and September 2022. All participants underwent preoperative aortic computed tomography angiography and echocardiography to confirm the diagnosis of Stanford type-A aortic dissection according to the Stanford classification. The acute phase of dissection was defined as the period from the onset of symptoms to hospital admission within a 14-day timeframe. The exclusion criteria included chronic diseases of the kidney, lung, gastrointestinal tract, and liver; autoimmune diseases; and malperfusion of the heart, brain, gut, liver, pancreas, kidney, or limbs. Of the initially admitted patients, 3 declined participation in the study, and an additional 3 met at least one exclusion criterion. Subsequently, the remaining 18 patients who underwent emergency total arch repair (TAR) combined with frozen elephant trunk (FET) procedure under hypothermic lower-body circulatory arrest and antegrade cerebral perfusion were enrolled in this study. Detailed descriptions of TAR combined with FET techniques are available elsewhere (18-20). Meanwhile, a control group consisting of 18 healthy volunteers attending our outpatient department was also included for comparison purposes.

Blood samples were aseptically obtained from patients at 4 time points during the perioperative period, including preoperatively, and 12-, 24-, and 48-hour postoperatively. Following centrifugation, serum samples were collected and stored at −80 ℃. The minimum sample size of 18 cases for each group was determined sufficient to achieve 80% statistical power and a significance level of 5%. This study was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and received approval from the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. GZR-046). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their immediate relatives.

Indicators and methods

Participant demographics and baseline characteristics

Participant data were collected through a comprehensive review of medical records, with demographic details, including age, sex, and relevant medical history [e.g., hypertension, coronary heart disease (CHD), cerebral infarction (CI), and diabetes]. Additionally, preoperative biochemical parameters were obtained, including creatinine (Cr), troponin I (TnI), glutamic pyruvic transaminase (GPT), glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT), myoglobin (Myo), and amylase (Amy).

Systemic inflammatory response levels

White blood cell (WBC) counts were obtained at 4 time points, including preoperative and 12-, 24-, and 48-hour postoperative, by reviewing medical records. Inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)6, IL8, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), were quantified in serum samples using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay technique (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The serum samples were obtained as previously described.

Hypoxemia, gut injury, bacteremia, and succinate levels

The severity of perioperative hypoxemia was evaluated by examining the PaO2/FiO2 ratio in the medical records at various time points, including preoperatively and 4, 8, and 12 hours after operation. Gut injuries were assessed through measurement of diamine oxidase (DAO) activity and intestinal fatty-acid-binding protein (iFABP) concentration in serum. Bacteremia levels were assessed through measurement of peptidoglycan (PGN) concentration in serum. DAO activity was evaluated with a spectrophotometer (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA), while iFABP and PGN concentrations were quantified using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (R&D Systems). Succinate concentrations in serum were determined using Succinate Colorimetric Assay Kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) for Windows. The normality of distribution was tested for continuous variables, which were expressed as mean ± standard deviation if the distribution was normal, and as median and interquartile range if the distribution was skewed. Qualitative variables are presented as rates. For continuous variables, comparisons between groups were made using independent samples t-tests for normal distribution, or Mann Whitney U-test for skewed distributions, while for qualitative variables, chi-square tests, corrected chi-square tests, or the Fisher exact probability test was applied. Analyses of covariance were employed to control for potential confounding variables in baseline characteristics as deemed necessary. Pearson correlation coefficient values were calculated to evaluate correlations. Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed on the variables at the 12-hour time point to identify the risk factors for hypoxemia at 12 hours after operation. The minimum sample size of 18 cases for each group was deemed sufficient to achieve 80% statistical power and a significance level of 5%, which was calculated using the online calculator Clincalc (https://clincalc.com/stats/samplesize.aspx). A two-sided P value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The variables in this study were found to be complete, and no values are missing.

Results

Participant demographics and baseline data

The study included 18 patients and 18 healthy controls. There were no notable disparities in the demographics or baseline data between the two cohorts (Table 1).

Table 1

| Baseline characteristics | ATAADs (n=18) | Controls (n=18) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48.06±10.40 | 44.78±2.69 | 0.21 |

| Men | 15 (83.3) | 15 (83.3) | >0.99 |

| Hypertension | 13 (72.2) | 16 (88.9) | 0.40 |

| CHD | 0 | 0 | – |

| CI | 0 | 0 | – |

| Diabetes | 0 | 1 (5.6) | >0.99 |

| Biochemical parameters | |||

| Cr (μmol/L) | 82.06±17.51 | 75.02±15.66 | 0.21 |

| TnI (pg/mL) | 8.95 (3.40, 37.20) | 5.45 (1.40, 13.00) | 0.09 |

| GPT (U/L) | 18.50 (14.75, 32.75) | 16.50 (12.75, 30.75) | 0.35 |

| GOT (U/L) | 22.00 (18.50, 26.25) | 17.50 (14.00, 32.00) | 0.30 |

| Myo (ng/mL) | 28.40 (19.15, 51.65) | 26.40 (17.15, 34.68) | 0.32 |

| Amy (U/L) | 55.21±30.49 | 42.22±16.41 | 0.12 |

Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, n (%), or median (P25, P75). Amy, amylase; ATAAD, acute type-A aortic dissection; CHD, coronary heart disease; CI, cerebral infarction; Cr, creatinine; GOT, glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; GPT, glutamic pyruvic transaminase; Myo, myoglobin; TnI, troponin I.

Operative data

All 18 patients with ATAAD underwent TAR combined with FET procedure under hypothermic lower-body circulatory arrest and antegrade cerebral perfusion. Detailed operative data, including surgical time, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) duration, lower-body circulatory arrest duration, aortic cross-clamp duration, lowest rectal temperature during CPB, intraoperative transfusion volumes of red blood cell suspension, and postoperative drainage volume within 12 hours are presented in Table 2.

Table 2

| Operative variables | TAR + FET |

|---|---|

| Surgery time (hours) | 6.85±1.48 |

| CPB time (minutes) | 179.94±36.77 |

| ACC time (minutes) | 96.22±28.56 |

| Circulatory arrest time (minutes) | 23.33±12.32 |

| Lowest rectal temperature during CPB (℃) | 28.49±3.00 |

| RBC transfusion (U) | 1.28±2.11 |

| Drainage (mL) | 623.33±406.17 |

Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. ACC, aortic cross-clamp; ATAAD, acute type-A aortic dissection; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; FET, frozen elephant trunk; RBC, red blood cell; TAR, total arch repair.

Systemic inflammatory response levels

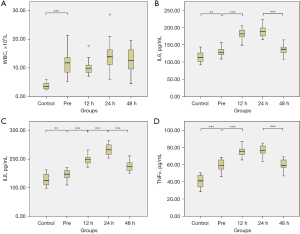

Patients with ATAAD, compared to controls, had a significantly elevated preoperative WBC count [(12.18±4.50)×109/L vs. (3.73±1.05)×109/L; P<0.001; Figure 1A] and serum levels of IL6 (129.31±12.86 vs. 114.22±14.11 pg/mL; P=0.002; Figure 1B), IL8 (147.57±16.03 vs. 127.56±20.23 pg/mL; P=0.002; Figure 1C), and TNFα (59.29±6.90 vs. 40.51±7.53 pg/mL; P<0.001; Figure 1D). In patients with ATAAD, postoperative levels of IL6, IL8, and TNFα following TAR combined with FET under hypothermic lower-body circulatory arrest and antegrade cerebral perfusion were significantly elevated as compared to preoperative levels. The peak postoperative levels of all three inflammatory cytokines occurred at 24 hours after the surgery procedure. There were no significant differences in postoperative WBC counts as compared to preoperative levels.

Levels of hypoxemia, gut injury, bacteremia, and succinate

The preoperative PaO2/FiO2 ratio was significantly lower in patients with ATAAD compared to controls (336.45±123.89 vs. 452.11±59.97 mmHg; P=0.002; Figure 2A). Furthermore, the postoperative PaO2/FiO2 ratio significantly decreased from the preoperative levels in patients with ATAAD, reaching its nadir at 12 hours’ postoperatively. Patients with ATAAD, compared to controls, also exhibited significantly elevated preoperative DAO serum (17.94±1.54 vs. 13.32±1.82 U/L; P<0.001; Figure 2B), and the postoperative levels of DAO and iFABP (Figure 2C) significantly increased from the preoperative levels, with the highest levels observed at 24 hours’ postoperation. The succinate reached its highest level prior to the operation in patients with ATAAD, which was significantly higher than those of controls (235.92±48.09 vs. 106.95±27.63 µM; P<0.001; Figure 2D), and remained elevated at both the 12- and 24-hour postoperative time points. In patients with ATAAD, the serum levels of PGN at 12 hours’ postoperation were found to be significantly higher as compared to the preoperative levels (265.95±27.76 vs. 179.86±28.94 ng/mL; P<0.001; Figure 2E).

Factors associated with postoperative hypoxemia

Correlation analyses were conducted to investigate the relationships between different variables at 12 hours’ postoperation, as well as the relationships between the variables at 12 hours’ postoperation and operative variables. The variable potentially correlated with the PaO2/FiO2 ratio at 12 hour’s postoperation included TNFα (r=−0.34; P=0.08), IL8 (r=0.43; P=0.04), DAO (r=0.36; P=0.07), intraoperative transfusion volumes of red blood cell suspension (r=0.41; P=0.05), and postoperative drainage volume within 12 hours (r=0.57; P=0.007). Furthermore, multivariate linear regression analysis identified PGN, iFABP, succinate, and lowest rectal temperature during CPB as risk factors for 12-hour postoperative hypoxemia (Table 3). The adjusted R2 of our model was 0.951 (R2=0.980), indicating that the linear regression explained 95.1% of the variance in the data.

Table 3

| Variables | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | T | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | Standard error | Beta | ||||

| Constant | −607.182 | 174.402 | – | −3.482 | 0.01 | |

| PGN | −0.986 | 0.210 | −0.329 | −4.700 | 0.002 | |

| IL6 | 2.064 | 0.376 | 0.381 | 5.485 | 0.001 | |

| IL8 | 0.729 | 0.328 | 0.151 | 2.223 | 0.06 | |

| iFABP | −0.414 | 0.065 | −0.539 | −6.348 | <0.001 | |

| DAO | 52.421 | 3.768 | 1.180 | 13.911 | <0.001 | |

| Succinate | −1.167 | 0.139 | −0.699 | −8.411 | <0.001 | |

| WBC | 9.505 | 2.363 | 0.299 | 4.022 | 0.005 | |

| ACC | 1.861 | 0.296 | 0.639 | 6.290 | <0.001 | |

| Lowest rectal temperature | −10.994 | 2.464 | −0.397 | −4.461 | 0.003 | |

| RBC transfusion | 54.036 | 3.963 | 1.370 | 13.634 | <0.001 | |

ACC, aortic cross-clamp; DAO, diamine oxidase; iFABP, intestinal fatty-acid-binding protein; IL, interleukin; PGN, peptidoglycan; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

Discussion

Acute hypoxemia is a life-threatening condition for patients with ATAAD (1-4). Systemic inflammatory reactions have been implicated as critical elements in the development of hypoxemia (1,2,5-12). Recent researches have indicated that patients also experience gut injury, which could potentially contribute to the progression of systemic inflammatory responses and hypoxemia (9,13). DAO and iFABP are specifically present in small intestinal mucosal cells, and serum DAO activity and iFABP levels reflect the integrity and degree of damage of the intestinal barrier and are established markers of intestinal barrier dysfunction (21-23). In a previous study, we found that DAO, iFABP, and PGN (which increases in serum in conditions of bacteremia) levels were elevated in the serum of patients with ATAAD, suggesting the occurrence of gut injury and intestinal bacterial translocation into the blood in these patients. In addition, significant correlations were detected between DAO, iFABP, IL6, IL8, TNFα, CRP, PGN, and PaO2/FiO2 ratio in the ATAAD group, suggesting that gut injury may play a role in the development of systemic inflammatory response and hypoxemia in these patients (9). Furthermore, researches conducted in murine models of ischemia-reperfusion gut injury have demonstrated the critical involvement of gut microbiota and gut microbe-derived succinate in the development of hypoxemia (14-17). However, the perioperative dynamic changes of systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, hypoxemia, and succinate in the blood of patients with ATAAD remain unclear. In this study, we examined the dynamic changes in systemic inflammatory response indicators, gut injury, hypoxemia, and succinate levels in patients with ATAAD and their impact on perioperative hypoxemia.

We found that the baseline characteristics of patients with ATAAD were comparable to those of controls, suggesting no organ malperfusion occurs in these individuals. However, prior to surgery, these patients exhibited systemic inflammatory responses, gut injury, and hypoxemia characterized by elevated WBC count and IL6, IL8, TNFα, and DAO levels, along with a decreased PaO2/FiO2 ratio. This observed gut injury does not fulfill the clinical diagnostic criteria for significant gut injury, as it lacks characteristic symptoms such as abdominal pain, hematochezia, elevated aminotransferase and Amy levels. Additionally, it is not attributable to malperfusion of the celiac trunk or superior mesenteric artery. Following TAR combined with FET operation under hypothermic lower-body circulatory arrest and antegrade cerebral perfusion, postoperative levels of IL6, IL8, TNFα, DAO, and iFABP were elevated and the PaO2/FiO2 ratio reduced as compared to preoperative levels. These findings indicate the aggravation of systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, and hypoxemia following the completion of these procedures. The impact of ATAAD on systemic inflammatory responses, gut injury, and hypoxemia in patients was examined in our previous study (8). Furthermore, the operative procedure exerts significant aggravating effects on these pathophysiological conditions, including surgical trauma from TAR combined with FET operation, harm induced by CPB, hypothermia, and circulation arrest during repair of the aortic arch (24). As a result, the systemic inflammatory responses are more pronounced in these patients and gut injury and hypoxemia more severe postoperatively.

A few recent studies reported that succinate may be the key molecule that links gut injury and hypoxemia in ischemia-reperfusion gut injury. The abundance of microbiota-derived succinate in blood is increased, which leads to the promotion of succinate receptor 1 (SUCNR1)-dependent polarization of alveolar macrophages, apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells, and subsequent lung injury during gut ischemia-reperfusion (14,16). In this study, we found that the preoperative serum levels of succinate were significantly increased in patients with ATAAD and remained elevated at both the 12- and 24-hour postoperative time points; moreover, its level at 12 hours after operation was one of the risk factors for 12-hour postoperative hypoxemia, which suggests that succinate may be involved in the aggravation of systemic inflammatory responses and hypoxemia in the patients with ATAAD.

This study involved several limitations that should be discussed. The primary limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size, which may have led to an overestimation or underestimation of the effect size. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted with caution and require validation in larger-scale studies. Second, although DAO activity, iFABP level, and PaO2/FiO2 ratio are widely recognized as excellent indicators of gut and lung injury severity, histological examinations confirming such injuries is preferred. Third, despite the observed increase in succinate levels in patients with ATAAD and its identification as one of the risk factors for postoperative hypoxemia, further investigation is necessary to determine the precise source of the elevated succinate levels in these patients and its role in hypoxemia. Nonetheless, this study provided novel insights into the perioperative dynamic changes of systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, and hypoxemia in patients with ATAAD, along with their functional implications on hypoxemia. Importantly, our work represents a crucial examination of the dynamic change of succinate and its correlation with postoperative hypoxemia in patients with ATAAD, which may prove valuable for guiding further studies on the mechanisms underlying gut and lung injury in patients with ATAAD. Additionally, total arch replacement combined with FET stent implantation has become the gold standard for the management of ATAAD and is widely accepted in China. Therefore, the findings of this study have significant implications for optimizing surgical strategies and standardizing management protocols for ATAAD in the Chinese healthcare context.

Conclusions

Preoperative systemic inflammatory response, gut injury, and hypoxemia were significantly aggravated in patients with ATAAD and further exacerbated following the TAR combined with FET procedure under hypothermic lower-body circulatory arrest and antegrade cerebral perfusion. Succinate may be crucially involved in the development of hypoxemia.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-141/rc

Data Sharing Statement: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-141/dss

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-141/prf

Funding: This work was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2025-141/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital, Capital Medical University (No. GZR-046). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or their immediate relatives.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Pan X, Lu J, Cheng W, et al. Independent factors related to preoperative acute lung injury in 130 adults undergoing Stanford type-A acute aortic dissection surgery: a single-center cross-sectional clinical study. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:4413-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao Z, Pei X, He C, et al. Oxygenation impairment in patients with acute aortic dissection is associated with disorders of coagulation and fibrinolysis: a prospective observational study. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:1190-201. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugano Y, Anzai T, Yoshikawa T, et al. Serum C-reactive protein elevation predicts poor clinical outcome in patients with distal type acute aortic dissection: association with the occurrence of oxygenation impairment. Int J Cardiol 2005;102:39-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo Z, Yang Y, Zhao M, et al. Preoperative hypoxemia in patients with type A acute aortic dissection: a retrospective study on incidence, related factors and clinical significance. J Thorac Dis 2019;11:5390-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vrsalović M, Vrsalović Presečki A. Admission C-reactive protein and outcomes in acute aortic dissection: a systematic review. Croat Med J 2019;60:309-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hsieh WC, Henry BM, Hsieh CC, et al. Prognostic Role of Admission C-Reactive Protein Level as a Predictor of In-Hospital Mortality in Type-A Acute Aortic Dissection: A Meta-Analysis. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2019;53:547-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vrsalovic M, Zeljkovic I, Presecki AV, et al. C-reactive protein, not cardiac troponin T, improves risk prediction in hypertensives with type A aortic dissection. Blood Press 2015;24:212-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yuan SM. Profiles and Predictive Values of Interleukin-6 in Aortic Dissection: a Review. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2019;34:596-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Zheng J, Jin X, et al. Intestinal barrier dysfunction is involved in the development of systemic inflammatory responses and lung injury in type A aortic dissection: a case-control study. J Thorac Dis 2022;14:3552-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kimura N, Machii Y, Hori D, et al. Influence of false lumen status on systemic inflammatory response triggered by acute aortic dissection. Sci Rep 2025;15:475. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Luo YX, Matniyaz Y, Tang YX, et al. Postoperative hyper-inflammation as a predictor of poor outcomes in patients with acute type A aortic dissection (ATAAD) undergoing surgical repair. J Cardiothorac Surg 2024;19:138. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duan XZ, Xu ZY, Lu FL, et al. Inflammation is related to preoperative hypoxemia in patients with acute Stanford type A aortic dissection. J Thorac Dis 2018;10:1628-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gu J, Hu J, Qian H, et al. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction: A Novel Therapeutic Target for Inflammatory Response in Acute Stanford Type A Aortic Dissection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 2016;21:64-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang YH, Yan ZZ, Luo SD, et al. Gut microbiota-derived succinate aggravates acute lung injury after intestinal ischaemia/reperfusion in mice. Eur Respir J 2023;61:2200840. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Souza DG, Vieira AT, Soares AC, et al. The essential role of the intestinal microbiota in facilitating acute inflammatory responses. J Immunol 2004;173:4137-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bongers KS, Stringer KA, Dickson RP. The gut microbiome in ARDS: from the "whether" and "what" to the "how". Eur Respir J 2023;61:2202233. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen J, Wang Y, Shi Y, et al. Association of Gut Microbiota With Intestinal Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022;12:962782. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma WG, Zheng J, Liu YM, et al. Dr. Sun's Procedure for Type A Aortic Dissection: Total Arch Replacement Using Tetrafurcate Graft With Stented Elephant Trunk Implantation. Aorta (Stamford) 2013;1:59-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma WG, Zhu JM, Zheng J, et al. Sun's procedure for complex aortic arch repair: total arch replacement using a tetrafurcate graft with stented elephant trunk implantation. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013;2:642-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li JR, Ma WG, Chen Y, et al. Total arch replacement and frozen elephant trunk for aortic dissection in aberrant right subclavian artery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2020;58:104-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo YY, Liu ML, He XD, et al. Functional changes of intestinal mucosal barrier in surgically critical patients. World J Emerg Med 2010;1:205-8.

- Zhang L, Fan X, Zhong Z, et al. Association of plasma diamine oxidase and intestinal fatty acid-binding protein with severity of disease in patient with heat stroke. Am J Emerg Med 2015;33:867-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Montagnana M, Danese E, Lippi G. Biochemical markers of acute intestinal ischemia: possibilities and limitations. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:341. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu W, Liang Y, Gao J, et al. Study on risk factors and treatment strategies of hypoxemia after acute type a aortic dissection surgery. J Cardiothorac Surg 2024;19:273. [Crossref] [PubMed]