Assessments and exercises of cough strength in critically ill patients: a literature review

Introduction

Background

Airway clearance is crucial for maintaining airway patency in critically ill patients and depends on the mucociliary escalator, expiratory flow, and cough strength (1). In patients receiving noninvasive ventilation (NIV) or high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy to prevent intubation or reintubation, a weak cough is a significant risk factor for therapy failure (2,3). In intubated patients, a strong cough alone is not a reliable predictor of successful extubation, as they may be reintubated for other reasons. However, a weak cough and large amounts of secretion are important predictors of extubation failure and reintubation (4-8). A weak cough is also associated with an increased incidence of tracheostomy, prolonged mechanical ventilation duration, extended hospital stays, and increased mortality (9-11). Critically ill patients with diseases of the airways, nerves, and muscles often exhibit a weak cough, particularly those with high-risk factors such as advanced age, obesity, smoking, diabetes, pulmonary infections, and recent surgeries (12). Therefore, assessing and exercising cough strength are especially important for managing critically ill patients.

There are significant differences between voluntary and involuntary coughs. The voluntary cough consists of three phases: the inspiratory phase, controlled by the volume of inhaled air; the compressive phase, characterized by elevated intrapulmonary pressure; and the expulsive phase, during which the glottis suddenly opens and strong coughs are produced by rapid airflow through the airways (13,14). The involuntary or protective cough consists of four phases (irritation, inspiration, compression, and expulsion) and can be induced by inhaling irritants, such as capsaicin in healthy patients, or by administering 2 mL of saline into the airways of patients with artificial airways (4,15). The primary neurophysiological difference in the mechanics of voluntary and involuntary coughs is that the latter originates in the brainstem (16,17). Notably, the expiratory and accessory muscles are more active during voluntary cough (18-20). The voluntary cough is activated to indicate the patient’s strength in clearing the airways, while the involuntary cough reflects the capacity to protect the airways. This distinction is particularly important for patients at higher risk of silent aspiration and aspiration pneumonia (18,20,21).

Objective

This review aims to summarize current practices in assessing and exercising cough strength. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1673/rc).

Methods

Literature search

We conducted a systematic search of the PubMed, Embase, and ScienceDirect using specific keywords for publications up to December 31, 2023. The search strategy included the following keywords: (“cough assessment” OR “cough intensity” OR “cough ability” OR “cough capacity” OR “cough strength” OR “cough strength score”). The search strategy summary is in Table 1. A total of 281 related articles were identified, and we ultimately enrolled 26 of them. The characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 2. Commonly used methods for assessing cough strength are summarized in Table 3. We also searched for cough exercises using the keywords: (“cough training” OR “cough exercise”). A total of 1,407 related articles were identified, and we ultimately enrolled 73 of them. The characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 4. This search aimed to identify all studies related to the assessment and exercises of cough ability in critically ill patients.

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | 2023/12/31 |

| Databases and other sources searched | PubMed, Embase and ScienceDirect |

| Search terms used | Cough assessment; cough intensity; cough strength; cough strength score; cough training; cough exercise |

| Timeframe | 2000.01.01–2023.12.31 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria: RCTs, non-randomized trials, observational studies (case-control, cohort, cross-sectional studies), proof-of-concept studies, research protocols, case reports or series |

| Exclusion criteria: subjects: hospitalized adult patients, language: non-English | |

| Selection process | S.M.Z. and Y.M. searched relative articles, S.M.Z. sorted out and classified the literature and K.L. controlled the direction and content of the review |

| Any additional considerations, if applicable | None |

Table 2

| Author, year | Country | Study | Patients | Methods | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003, Smina M (22) | America | Cohort | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=95) | PEF | PEF and the rapid shallow breathing index were independently associated with extubation outcomes, while only the PEF (< or = 60 L/min) was independently associated with in-hospital mortality |

| 2009, Gao XJ (23) | China | Prospective | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=200) | CPF | CPF is a strong and independent predictor of extubation outcome when the patient is mentally clear and has a successful SBT. When the CPF >58.5 L/min, the successful rate is high. On the contrary, when the CPF < or =58.5 L/min, the unsuccessful rate is high |

| 2009, Beuret P (24) | France | Prospective | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=130) | PEF | The interest of measuring the PEF to predict extubation outcome in patients having successfully passed the spontaneous breathing trial |

| 2010, Su WL (15) | China | Evaluation study | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=150) | CPFi | CPFi as an indication of cough reflex has the potential to predict successful extubation in patients who pass an SBT |

| 2013, Lee SC (25) | Korea | Cross-sectional study | TBI (n=25) and healthy (n=48) | CPF vs. LCR | As LCR can be measured as a numerical value and significantly correlates with CPF, LCR can be used to estimate cough ability of patients with TBI who cannot cooperate with CPF measurement |

| 2014, Fan L (26) | China | Prospective observational | AECOPD receiving NIV (n=261) | SCSS | AECOPD patients with weak cough had a high risk of NIV failure. SCSS, APACHE II scores, and total proteins were predictors of NIV failure. Combined, these factors increased the power to predict NIV failure |

| 2014, Duan J (27) | China | – | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=115) | V-CPF vs. IV-CPF | V-CPF is noninvasive. It is much more accurate than IV-CPF as a predictor of re-intubation in cooperative patients because the IV-CPF may underestimate cough strength in patients with high V-CPF |

| 2015, Duan J (28) | China | – | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=186) | SCSS | SCSS was convenient to measure at the bedside. It was positively correlated with CPF and had the same accuracy for predicting reintubation after planned extubation |

| 2016, Kulnik ST (29) | UK | Clinical trial | Stroke (N=72) | CPF | Risk of pneumonia reduces with increasing CPF of voluntary and to a lesser degree with increasing CPF of reflex cough |

| 2017, Gobert F (30) | France | Prospective observational study | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=92) | CPF measured using the flow meter of an ICU ventilator and Vt | After dichotomization (CPF < –60 L/min or Vt >0.55 L), there was a synergistic effect to predict early extubation success |

| 2017, Lee KK (31) | UK | – | Patients with chronic cough (N=32) | Sound power and energy of cough | Cough sound power and energy correlate strongly with physiological measures and subjective perception of cough strength. Power and energy are highly repeatable measures but the microphone position should be standardised |

| 2018, Umayahara Y (32) | Japan | – | Healthy (N=88) | Cough sounds | The absolute error between CPFs and estimated CPFs were significantly lower when the microphone distance from the participant’s mouth was within 30 cm than when the distance exceeded 30 cm |

| 2018, Umayahara Y (33) | Japan | – | Healthy (N=58) | Young vs. elder | Developed device can be applied for daily CPF measurements in clinical practice |

| 2018, Aguilera LG (34) | Spain | Retrospective | Preoperative patients (N=9) | Pes, Pga, Pcv, Pbl, Prec | Cough pressure can be measured in the esophagus, stomach, superior vena cava or rectum, since their values are similar. It can also be measured in the bladder, although the value will be slightly higher |

| 2018, Sohn D (35) | Korea | Retrospective analysis of a prospective maintained database | Dysphagia (n=163) | Reflexive PCF | Those with reflexive cough strength less than 59 L/min may be at high risk of respiratory infections within the first 6 months after dysphagia onset |

| 2018, Ibrahim AS (36) | Egypt | Prospective observational study | TBI (n=80) | SCSS and GCS | SCSS has shown promise in predicting successful extubation in TBI |

| 2019, Morrow BM (37) | South Africa | Retrospective descriptive study | NMD (n=41) | PEF, FVC, CPF | Peak expiratory flow < 160 L·min-1 and FVC <1.2 L were significantly predictive of CPF <160 L·min-1 (suggestive of cough ineffectiveness), whilst PEF <250 L·min-1 was predictive of CPF <270 L·min-1, the level at which cough assistance is usually implemented |

| 2019, Norisue Y (38) | Japan | Physiologic study | Healthy adults (n=56) | Passive cephalic movement of the diaphragm | Passive cephalic excursion of the diaphragm during the cough expiratory phase significantly predicted CPF with maximum cough effort in healthy adults |

| 2020, Froutan R (39) | Iran | RCT | – | PEF vs. WCT | Using the cough PEF rate increases the likelihood of extubation success and reduces adverse effects, and is recommended to be used for extubation decision-making |

| 2020, O'Neill MP (40) | Durban | Prospective observational | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=42) | ΔPcuff | CPF =60 L/min equates to ΔPcuff =28 cmH2O |

| 2021, Chang S (41) | China | Retrospective | Postoperative lung cancer (n=560) | Preoperative PEF | A PEF value of 250 L/min was selected as the optimal cutoff value in female patients, and 320 L/min in male patients. Patients with PEF under cutoff value of either sex had higher PPCs rate and unfavorable clinical outcomes |

| 2021, Norisue Y (42) | Japan | Prospective cohort study | Endotracheally intubated patients (n=252) | Passive cephalic excursion of the diaphragm | PCED on ultrasonography was significantly associated with CPF and extubation failure after a successful SBT |

| 2023, Bonny V (43) | France | Prospective observational study | Endotracheally intubated patients (n=106) | Sonometric assessment of cough | A threshold of Sonoscore <67.1 dB predicted extubation failure with a sensitivity of 0.93 and a specificity of 0.82 |

| 2023, Lee KW (44) | Korea | Retrospective pilot | PD (n=219) | CPF | A PCF value ≤153 L/min was associated with an increased risk of aspiration |

| 2023, Tabor Gray L (45) | Finland | – | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (n=62) | MPT | MPT is a simple clinical test that can be measured via telehealth and represents a potential surrogate marker for important respiratory and airway clearance indices |

| 2023, Recasens BB (46) | Spain | Cohort | NMD (n=50) | CPF | The smartphone app had 94.4% sensitivity and 100% specificity to detect patients with CPF <270 L/min |

PEF, peak expiratory flow; SBT, spontaneous breathing trial; CPF, cough peak flow; TBI, traumatic brain injury; LCR, laryngeal cough reflex; AECOPD, acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; SCSS, semi-quantitative cough strength score; Vt, tidal volume; ICU, intensive care unit; VAS, visual analogue scale; GCS, Glasgow coma scale; NMD, neuromuscular disorders; FVC, forced vital capacity; RCT, randomized controlled trial; WCT, white card test; PPCs, postoperative pulmonary complications; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; PCED, passive cephalic excursion of diaphragm; PD, Parkinson disease; MPT, maximum phonation time.

Table 3

| Assessment methods | Patients (ET/Tra/no-tube) | High-risk | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPF/PEF (4,15,22-25,27,30,35,37,41,44,47-55) | No-tube: CPF; ET/Tra: PEF | Healthy adults: CPF <270 L/min | Easy, noninvasive, widely used, quantified | Accuracy varies among instruments |

| Neuromuscular disease patients: CPF <160 L/min | ||||

| After extubation: CPF <160 L/min | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation patients: PEF <60 L/min | ||||

| SCSS (4,26,28,36,56-59) | All | Score <3 | Easy, noninvasive | Subjective |

| Requires experienced evaluators | ||||

| WCT (4,39,57) | ET/Tra | Negative | Easy, noninvasive, high sensitivity | Subjective |

| Cannot evaluate passive cough | ||||

| Diaphragm ultrasound (38,42,60-65) | All | – | Easy, noninvasive, widely used, quantified | Easily influenced by age, sex, and height. Differences between males and females |

| ΔPcuff (40) | ET/Tra | 28 cmH2O equals to CPF 60 L/min; <20 cmH2O predicts extubation failure | Easy, noninvasive, quantified | Easily influenced by size and position of the artificial airway |

| Cough sound (31-33,45,46) | No-tube | – | Easy, noninvasive, quantified | Related to distance between the microphone and patient’s mouth |

| Sonoscore (43) | ET | <61.7 dB | Easy, noninvasive, quantified | No more related data/studies |

| EMG (66,67) | All | – | Quantified | Invasive |

| Influenced by activities of the heart and other muscles | ||||

| Pes, Pgas, Pcv, Pbla, Prec (34) | All | – | Quantified | Invasive |

| Cautious in post thoracic/abdominal surgeries patients |

ET, endotracheal intubation; Tra, tracheotomy tube; CPF, cough peak flow; PEF, peak expiratory flow; SCSS, semiquantitative cough strength score; WCT, white card test; EMG, electromyography; Pes, esophageal pressure; Pgas, internal gastric pressure; Pcv, central venous pressure; Pbla, bladder pressure; Prec, rectal pressure.

Table 4

| Year, author | Groups | Patient | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1996, Nakamura S (68) | Flutter | Chronic respiratory diseases (N=17) | Flutter can increase the expectoration of sputum and can relieve related symptoms |

| 2000, Savci S (69) | AD vs. ACBT | COPD (N=30) | Autogenic drainage is as effective as the ACBT in cleaning secretions and improving lung functions |

| 2003, Toussaint M (70) | IPV vs. without IPV | DMD (N=8) | IPV increases the effectiveness of assisted mucus clearance techniques |

| 2004, Berney S (71) | Head-down tilt | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=20) | Head-down tilt and manual hyperinflation increase sputum production and improve PEF |

| 2004, Winck JC (72) | Different pressure of MIE | Chronic ventilatory failure (N=29) | MIE may be a potential complement to noninvasive ventilation for a wide variety of patient groups |

| 2004, Sancho J (73) | MIE | ALS (N=26) | MIE is able to generate clinically effective PCFMI-E (>2.7 L/s) for stable patients with ALS, except for those with bulbar dysfunction who also have a MIC >1 L and PCFMIC <2.7 L/s who probably have severe dynamic collapse of the upper airways during the exsufflation cycle |

| 2006, McCarren B (74) | Vibration vs. Acapella, Flutter, PEP, percussion | CF (N=18) | Mean peak expiratory flow rate of vibration was greater |

| 2006, Kang SW (55) | Unassisted PCF vs. three different techniques of assisted PCF | DMD (N=32) | Combined assisted cough technique (both manual and volume assisted PCF) significantly exceeded manual assisted PCF and volume assisted PCF |

| 2006, Lange DJ (75) | HFCWO vs. control | ALS (N=46) | In patients with impaired breathing, high-frequency chest wall oscillation decreased fatigue and showed a trend toward slowing the decline of forced vital capacity |

| 2007, Spivak E (76) | Self-controlled | Tetraplegia (N=10) | Abdominal FES failed to improve respiratory function in this study, but applying FES to abdominal muscles by EMG from the patient’s muscle may promote caregiver-free respiration and coughing |

| 2009, Durmuş D (77) | Conventional vs. Global Posture Reeducation vs. control | Ankylosing spondylitis (N=51) | Both exercises are efficient in improving pulmonary functions. Improved in pulmonary function tests were greater in the patients who performed the exercise according to global posture reeducation method |

| 2009, Chatwin M (78) | CPT+MIE vs. CPT | NIV (N=8) | The device appeared to be safe and well tolerated, and may provide additional benefit to patients with neuromuscular disease and upper-respiratory-tract infection |

| 2010, Barros GF (79) | RMT vs. control | CABG (N=38) | RMT performed in this phase was effective to restore the ventilatory capacity in the following parameters: MIP, MEP, PEF and tidal volume, in this group of patients |

| 2010, Neligan PJ (80) | NIV vs. COT | OSA (N=40) | NIV given immediately after extubation significantly improves spirometric lung function at 1 hour and 1 day postoperatively |

| 2010, Sutbeyaz ST (81) | IMT vs. breath training vs. control | Stoke (N=45) | IMT improves exercise capacity, sensation of dyspnea and quality of life |

| 2011, Pangborn J (82) | IS vs. control | Sickle cell anaemia (N=49) | Locally designed incentive spirometry improved PEF |

| 2011, Chicayban LM (83) | Flutter vs. control | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=20) | Flutter Valve improves lung secretion removal, mucus production, respiratory mechanics, and arterial oxygenation |

| 2012, Matheus GB (84) | IMT vs. control | CABG (N=47) | Muscle training was performed to retrieve TV and VC in the PO3, in the trained group |

| 2012, Nery FPOS (85) | CPAP vs. control | Lung resection (N=30) | When compared to breathing exercises, CPAP increases the 6MWD in postoperative lung resection patients, without prolonging air leak through the chest drain |

| 2013, Cleary S (86) | Manual breath stacking technique vs. control | ALS (N=29) | Lung volume recruitment may be an effective treatment for improving coughing and pulmonary function in individuals with ALS |

| 2013, Venturelli E (87) | TPEP vs. control | Chronic lung disease (N=98) | Temporary positive expiratory pressure improves lung volumes and speeds up the improvement of bronchial encumbrance in patients with lung diseases and hypersecretion |

| 2013, McBain RA (88) | Cough training combined with FES | SCI (N=15) | Six weeks of cough training further increases gastric and esophageal cough pressures and expiratory cough flow during stimulated cough maneuvers |

| 2014, Kim J (89) | Exercise vs. control | Stoke (N=20) | Exercise of the respiratory muscles using an individualized respiratory device had a positive effect on pulmonary function and exercise capacity and may be used for breathing rehabilitation in stroke patients |

| 2014, Mellies U (90) | Titration from 10 to 40mbar using IPPB/LIAM | Healthy (N=60) | A submaximal insufflation is ideal for generating the best individual PCF even in patients with severely reduced compliance of the respiratory system. Optimum insufflation capacity can be achieved using IPPB or LIAM with moderate pressures |

| 2014, Lacombe M (91) | IPPB+MAC vs. MIE vs. MIE+MAC | Neuromuscular (N=18) | PCF was higher with IPPB + MAC |

| 2014, Kulnik ST (92) | IMT vs. EMT vs. sham RMT | Stoke (N=60) | RMT is effective for improving cough strength, IMT is effective for improving MIP and EMT is effective for improving MEP. RMT is effective for reducing the incidence of pneumonia |

| 2014, Liu X (93) | Fibrobronchoscopic drainage | AECOPD (N=102) | The application of fibrobronchoscopy in the extubated AECOPD patients with low CPF can reduce the rate of re-intubation, avoid the prolonged ventilation, but cannot reduce the time of ICU stay |

| 2014, Tokuda M (94) | TENS vs. control | Abdominal surgery (N=49) | TENS is a valuable treatment to alleviate postoperative pain and improve pulmonary functions (i.e., VC, CPF) in patients following abdominal surgery |

| 2014, Esguerra-Gonzales A (95) | CPT vs. HFCWO | Lung transplant (N=45) | Lung function (measured by Spo2/FiO2) improves with HFWCO after lung transplantation. dyspnea and PEF did not differ significantly between treatment types, HFCWO may be an effective, feasible alternative to CPT |

| 2014, Aslan GK (96) | RMST vs. sham | Neuromuscular diseases (N=26) | Respiratory muscle strength improved by inspiratory and expiratory muscle training in patients with slowly progressive neuromuscular disease |

| 2014, Amelina EL (97) | Vibration-compression therapy vs. CPT | CF (N=31) | Incorporation of vibration-compression therapy (Vest vibro drainage) into the combination treatment of adult patients with CF results in significantly improved bronchial patency and more effective abolishment of an exacerbation |

| 2014, Guimarães FS (98) | ERCC vs. control | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=20) | Although ERCC increases expiratory flow, it has no clinically relevant effects from improving the sputum production and respiratory mechanics in hypersecretive mechanically ventilated patients |

| 2015, Liao LY (99) | Respiratory rehabilitation exercise training package vs. control | AECOPD (N=61) | Respiratory rehabilitation exercise training package reduced symptoms and enhanced the effectiveness of the care of elderly inpatients with AECOPD |

| 2015, Postma K (100) | Resisted IMT vs. control | SCI (N=40) | Improvement in respiratory muscle strength is associated with improvement in cough capacity in persons with recent spinal cord injury who have impaired pulmonary function |

| 2015, Kulnik ST (101) | Expiratory vs. inspiratory vs. sham training | Stroke (N=82) | Respiratory muscle function and cough flow improve with time after acute stroke. Additional inspiratory or expiratory respiratory muscle training does not augment or expedite this improvement |

| 2015, Reyes A (102) | Training vs. control | Huntington’s disease (N=18) | A home-based respiratory muscle training program appeared to be beneficial to improve pulmonary function in manifest Huntington's disease patients but provided small effects on swallowing function, dyspnoea and exercise capacity |

| 2016, Zeren M (103) | IMT vs. control | Atrial fibrillation (N=38) | Inspiratory muscle training can improve pulmonary function, respiratory muscle strength and functional capacity in patients with atrial fibrillation |

| 2016, Choi JY (104) | IS vs. control | Spastic cerebral palsy (N=50) | The use of IS for enhancing pulmonary function and breath control for speech production |

| 2016, Tallner A (105) | E-training vs. control | MS (N=126) | E-training had no effect on HrQoL but did on muscle strength, lung function, and physical activity |

| 2016, Hegland KW (106) | EMST | Ischemic stroke (N=14) | EMST improves expiratory muscle strength, reflex cough strength, and urge to cough |

| 2016, Kim SM (107) | Unassisted vs. manually assisted following a MIC maneuver vs. MIE assisted vs. manual thrust+MIE | NMD (N=40) | MI-E alone was more effective than manual assistance following an MIC maneuver, MI-E used in conjunction with manual thrust improved PCF even further |

| 2016, Toussaint M (70) | Home-ventilator group vs. resuscitator-bag group | DMD (N=52) | Both methods achieved mean air stacking-assisted cough peak flow values of >160 L/min |

| 2016, Jo MR (108) | Intervention vs. control | Stoke (N=42) | The increase in maximal expiratory pressure plays an important role in improving the cough capacity of stroke patients |

| 2017, Dwyer TJ (109) | control vs. treadmill exercise vs. Flutter | CF (N=24) | A single bout of treadmill exercise and Flutter® therapy were equally effective in augmenting mucus clearance mechanisms |

| 2018, Nicolini A (110) | CPT+IPV vs. CPT+ HFCWO vs. CPT |

COPD (N=60) | Both IPV and HFCWO can improve lung function, muscular strength, dyspnea, and scores on health status assessment scales, and IPV performs better |

| 2018, Jung JH (111) | MIE vs. control | NMD and pneumonia (N=27) | Increased peak cough flow after MIE application persists for at least 45 minutes |

| 2018, Li P (112) | Acapella vs. control | Video-assisted thorascopic surgery (N=69) | The application of OPEP device during the perioperative period was valuable in decreasing PPCs and enhancing recovery |

| 2018, Reyes A (113) | IMT vs. EMT vs. control | PD (N=31) | EMT program was more beneficial than IMT program for improving MEP and voluntary PCF |

| 2019, Oliveira ACO (114) | Without MCC vs. other three with MCC | Endotracheally intubated patients (N=10) | The PEEP-ZEEP maneuver, without MCC, resulted in an expiratory flow bias superior to that necessary to facilitate pulmonary secretion removal. Combining MCC with the PEEP-ZEEP maneuver increased the expiratory flow bias, which increases the potential of the maneuver to remove secretions |

| 2019, Jang KW (115) | Mechanical inspiration and expiration exercise vs. control | Subacute stoke (N=36) | Mechanical inspiration and expiration exercise had a therapeutic effect on velopharyngeal incompetence in subacute stroke patients with dysphagia |

| 2019, Alves WM (116) | RST vs. control | PD (N=28) | Sixteen weeks of strength training improves the inspiratory and expiratory muscle strength and QoL of elderly with Parkinson disease |

| 2019, Xavier VB (117) | Experimental vs. control | Adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis (N=40) | The experimental group also improved more than the control group on several respiratory measures, including FEV1, MIP, PEF |

| 2019, Zeren M (103) | IMT+CPT vs. CPT | CF (N=36) | Combining IMT with chest CPT failed to provide further improvements, except for MIP |

| 2020, Riboldazzi G (118) | Standard therapy vs. EFA | PD (N=25) | EFA® technology in Parkinson's patients with dysphagia to reduce the risk of respiratory complications |

| 2020, Sundar KM (119) | CPAP vs. sham CPAP | Chronic cough and OSA (N=22) | Treatment of comorbid OSA in patients with chronic cough improved cough quality of life measures following treatment of OSA with CPAP in this pilot study |

| 2021, Nicolini A (120) | MIE+EFA vs. MIE | ALS (N=30) | The cough-assist device with EFA technology performed better than a traditional MIE device in ALS patients regarding respiratory function and cough efficacy, although number of exacerbations and acceptability of the two devices was similar |

| 2021, Allam NM (121) | CPT vs. TCPT+HFCWO | Smoke inhalation injury (N=60) | Pulmonary function increased in both groups, they increased significantly in group with HFCWO posttreatment |

| 2021, Schindel CS (122) | CPAP (PEEP 10 cmH2O) vs. CPAP with minimum PEEP at 1 cmH2O | Severe therapy-resistant asthma (N=13) | The results suggest that the use of CPAP before physical exercise increases exercise duration |

| 2022, Aydoğan Arslan S (123) | IMT vs. control | Stroke (N=21) | IMT improved inspiratory muscle strength and trunk control |

| 2021, Cabrita B (124) | IMT | Neuromuscular diseases (N=21) | Significant improvements on pulmonary muscles function and might be considered as an adjunct treatment to neuromuscular treatment |

| 2021, Emirza C (125) | EMST vs. sham | CF (N=28) | EMST could improve PCF, MIP, MEP, treatment burden, digestive symptoms, functional exercise capacity and vitality domains of QoL in patients with CF |

| 2021, Srp M (126) | EMST vs. non-training | MS (N=35) | EMST improves expiratory muscle strength and voluntary cough strength in severely disabled MS patients |

| 2021, Liu GX (127) | Effective vs. ineffective | Underwent lung surgery (N=153) | PEF can be used as a quantitative indicator of cough ability. Chest wall compression could improve cough ability for patients who have ineffective cough |

| 2022, Hung TY (128) | AWT vs. AWT + CM vs. control | PMV (N=40) | AWT can significantly improve lung function, respiratory muscle strength, and cough ability in the PMV patients. AWT + CM can further improve their expiratory muscle strength and cough ability |

| 2022, Martí JD (129) | Different pressure sets | Pigs (N=6) | MI-E appeared to be an efficient strategy to improve mucus displacement during invasive ventilation, particularly when set at +40/-70 cmH2O |

| 2022, Çelik M (130) | HFCWO vs. control | COVID-19 (N=100) | High-frequency chest wall oscillation device contributed to the improvement of oxygenation by providing significant improvement as observed in the pulmonary function tests of the patients |

| 2023, Bito SAF (131) | High-intensity RMT vs. control | PD (N=34) | High-intensity respiratory muscle training improves muscle strength, functional outcomes, and quality of life in individuals with PD |

| 2023, Basbug G (132) | IMT vs. control | Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (N=36) | FEV1, PEF, MIP, MEP and 6MWT distance significantly improved in both groups. IMT group also showed significant improvement in FVC |

| 2023, Plowman EK (133) | RST vs. sham | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (N=45) | RST represents a proactive rehabilitative intervention that could increase physiologic capacity of specific breathing and airway clearance functions during the early stages of ALS |

| 2023, Ji X (134) | ACBT vs. routine care | Lung cancer (N=64) | ACBT combined with the Watson Theory of Human Caring can better restore LF in patients with LC following surgery, so as to promote rapid recovery and reduce postoperative complications |

| 2023, Troche MS (135) | EMST vs. smTAP | PD and dysphagia (N=65) | The efficacy of smTAP to improve reflex and voluntary cough function, above and beyond EMST, the current gold standard |

| 2023, Srp M (126) | EMST | Multiple system atrophy (N=15) | After the training period, MEP significantly increased, non-significant differences in vPCF after 8 weeks of EMST |

| 2023, Yoo SD (136) | Transcranial magnetic stimulation vs. control | Supratentorial cerebral infarction (N=145) | The combination of conventional rehabilitation and transcranial magnetic stimulation in the subacute period may be helpful in improving voluntary cough function |

AD, autogenic drainage; ACBT, active cycle breath technology; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IPV, intrapulmonary percussion ventilation; DMD, Duchenne muscular dystrophy; PEF, peak expiratory flow; MIE, mechanical insufflation exsufflation; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CPF, cough peak flow; MIC, maximum insufflation capacity; PEP, positive expiratory pressure; HFCWO, high frequency chest wall oscillation; FES, functional electrical stimulation; IMT, inspiratory muscle training; CPT, chest physical therapy; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; MEE, maximal expiratory effort; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; TPEP, therapeutic positive expiratory pressure; SCI, spinal cord injury; IPPB, intermittent positive pressure breath; LIAM, lung insufflation assist maneuver; MAC, manually assisted coughing; AECOPD, acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICU, intensive care unit; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; VC, vital capacity; R(M)ST, respiratory (muscle) strength training; CF, cystic fibrosis; ERCC, expiratory rib cage compression; MS, multiple sclerosis; NMD, neuromuscular disease; PPC, postoperative pulmonary complication; PD, Parkinson disease; MCC, manual chest compression; PEEP, positive end expiratory pressure; ZEEP, zero end expiratory pressure; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in first 1 second; MIP, maximum inspiratory pressure; MEP, maximum expiratory pressure; 6-MWT, 6 meter walking test; FVC, forced vital capacity; IS, incentive spirometer; EMST, expiratory muscle strength training; AWT, abdominal weight training; CM, cough machine; PMV, permanent mechanical ventilation; EFA, expiratory flow accelerator; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; OSA, obstructive apnea; OPEP, oscillating positive expiratory pressure; RMT, respiratory muscle training; IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; COT, conventional oxygenation therapy; EMG, electromyography; LF, lung function; LC, lung cancer; smTAP, sensorimotor training for airway protection; vPCF, voluntary peak cough flow; LF, lung function; LC, lung cancer; smTAP, sensorimotor training for airway protection; vPCF, voluntary peak cough flow.

Eligibility criteria

We included the following types of literature: randomized controlled trials, non-randomized trials, observational studies (case-control, cohort, and cross-sectional studies), proof-of-concept studies, research protocols, and case reports or series. Studies were eligible if they met these criteria: Subjects: Hospitalized adult patients. Language: Publications in English, including full-text articles or abstracts.

Data abstraction

Two independent evaluators reviewed all selected studies based on the inclusion criteria outlined above. In cases of discrepancies in data extraction or assessment, a single investigator was consulted to resolve the inconsistencies. The following information was extracted from each study: author(s), publication year, country, study type, sample size, patient characteristics (e.g., medical conditions), assessment method, conclusions/results and other relevant information.

Assessing cough strength

Cough peak flow (CPF) and peak expiratory flow (PEF)

CPF measures the maximum expiratory flow during a patient’s cough after a complete deep inspiration, with the glottis first closed and then opened. CPF is regarded as the gold standard for assessing cough strength and is significantly influenced by disease status and the overall physical condition of patients (24,47). A CPF <270 L/min indicates a weakened cough in healthy adults, while a CPF <160 L/min in patients with neuromuscular disorders and dysphagia is associated with a high risk of infectious pneumonia (44). Additionally, patients with a CPF <160 L/min immediately after extubation are at high risk of reintubation (48-50). PEF measures the maximum expiratory flow after a complete deep inspiration through an open glottis, and is therefore generally lower than CPF. In intubated patients, CPF and PEF are often used interchangeably in several studies (23-25,35,41). In fact, PEF is more suitable for assessing cough strength in intubated and tracheostomized patients because the artificial airway inhibits glottis closure, thus affecting the compressive phase of cough (48). Compared to other methods for assessing cough intensity, a PEF <60 L/min is the strongest predictor of extubation failure and is independently associated with in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients (4,22).

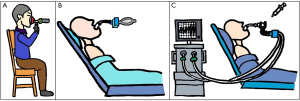

Plethysmography is the most accurate method for calculating CPF; however, it can be challenging to use with patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). A flowmeter is preferable for measuring CPF/PEF at the bedside, although accuracy can vary among different instruments (51). In non-intubated patients, CPF can be measured using a flowmeter and a mask. In intubated or tracheostomized patients, PEF can be directly measured using built-in flowmeters in the ventilator, based on the flow-time curve generated during pressure support ventilation [pressure support: 6–8 cmH2O; positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP): <5 cmH2O] when patients exert maximum effort to cough. This method is more convenient for patients with artificial airways (30). PEF can also be measured using a separate flowmeter connected to the ventilator pipeline, and its accuracy is typically superior to that of built-in instruments (4). For patients who cannot cooperate, involuntary cough can be induced by administering 2 mL of saline into the airway and then connecting the flow spirometer as quickly as possible (15,27). Occasionally, 2 mL of saline may not be sufficient to induce involuntary cough in patients, and an additional injection of normal saline may be considered (52). The effectiveness of voluntary versus involuntary coughs in assessing PEF remains controversial. Some studies have found that PEF obtained during voluntary cough, rather than involuntary cough, is a better predictor of reintubation (27). However, Almeida et al. reported no significant difference in reintubation rates among the voluntary cough, saline stimulus, and suction tube stimulus groups (53). Common methods for measuring CPF/PEF are summarized in Figure 1.

All factors that can influence any of the four phases of the cough reflex can theoretically also influence CPF/PEF(37). Moreover, forced vital capacity and maximum inspiratory pressure are both highly sensitive to decreased cough strength (54). However, unlike CPF/PEF, the following volume and pressure measurements—including forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume in the first second, vital capacity, functional residual capacity, maximum inspiratory pressure, and maximum expiratory pressure—are not predictive of extubation failure (54,55).

Semiquantitative cough strength score (SCSS)

The SCSS, first proposed by Khamiees et al. in 2001, is an objective measurement of cough strength ranging from 0 to 5, as follows: 0= no cough on command, 1= audible movement of air without an audible cough, 2= weakly audible cough, 3= clearly audible cough, 4= strong cough, and 5= multiple sequential strong coughs. It can be used to assess cough strength in patients with or without an artificial airway (56,57). The SCSS is useful for bedside assessments and is highly repeatable among experienced respiratory therapists. When comparing SCSS with PEF, an SCSS score of 3 corresponds to a PEF of 60 L/min (28). The predictive power of the SCSS is slightly lower than that of PEF, although its specificity is higher (4,58,59). Notably, the SCSS, when combined with another relevant index of extubation outcomes, such as the Glasgow Coma Scale, can provide a more reliable predictive model (36). The SCSS can also be used to assess non-intubated patients and predict the failure of NIV (26).

White card test (WCT)

The WCT is used to assess cough strength in patients with artificial airways. The WCT requires the patient to cough 3–4 times toward a white card placed approximately 1–2 cm in front of the endotracheal cannula. If secretions are present or the card becomes wet, it is considered a positive result, providing an initial impression of the amount and characteristics of the secretions (39). The extubation failure rate associated with negative WCT results is three times greater than that associated with positive results (57). However, compared to PEF, a PEF <60 L/min is a superior predictor of extubation failure compared to a negative WCT result (39). Although relatively few studies have reported direct comparisons between the WCT and SCSS, the WCT is generally more accurate (4). Additionally, it is important to note that a positive WCT result may be influenced by the evaluator’s subjective judgment, particularly when the card is only slightly wet, which presents a disadvantage of the WCT.

Diaphragm ultrasound

Diaphragm ultrasound is a noninvasive and convenient imaging modality that is highly repeatable and can be easily performed in the ICU. It can be used to assess cough strength in patients with or without artificial airways (60). The passive excursion of the diaphragm refers to the distance it moves from its original position during end-expiration to end-inspiration (38,61). Passive diaphragm excursion during expiration in healthy adults has been shown to significantly correlate with CPF when coughing with maximum effort (42). Furthermore, diaphragm excursion is greater during involuntary cough than during voluntary cough (62). Diaphragm thickening fraction (DTF) refers to the change in diaphragm thickness when the patient breathes deeply with maximum effort and is calculated as follows: [(end-inspiration thickness) – (end-expiration thickness)]/(end-expiration thickness). DTF correlates with diaphragmatic activity and reflects the work of breathing of the diaphragm (63,64). However, no studies have investigated the association between DTF and cough strength. Based on current evidence, diaphragm ultrasound is inappropriate as a sole criterion for assessing cough strength, as the results are influenced by sex, age, height, position during the examination, and the technician’s experience (65).

Cuff pressure change (ΔPcuff)

The difference between peak and baseline cuff pressure is defined as ΔPcuff (40). Generally, a cuff pressure gauge (cuff manometer) is used to monitor changes in the pressure of laryngeal masks and intubation tubes before and after coughing. It can only assess cough strength in patients with artificial airways. ΔPcuff is highly correlated with PEF, and the cutoff value for predicting extubation failure is reportedly 28 cmH2O (40). However, changes in cuff pressure can be influenced by bronchial and lung compliance, the measurement method, and the diameter of the cannula.

Other methods

Cough sound power and energy are strongly correlated with physiological measures, such as esophageal pressure and CPF, as well as the subjective perception of cough strength (31,46). This method can be used to assess cough strength in patients without artificial airways. Umayahara et al. (32) established a model to accurately calculate CPF based on cough sounds collected using a microphone positioned less than 30 cm from the patient’s mouth (33). This method could be particularly useful for non-intubated patients using speaking valves. Maximum phonation time is also a surrogate marker for respiratory function and airway clearance indices (45). However, more evidence is needed for its application in the ICU.

Sonoscore is the average decibel level of three consecutive coughs performed with maximum effort. Currently, there is only one related study that involved patients receiving invasive mechanical ventilation (43). The results indicated that a Sonoscore <67.1 dB was able to predict extubation failure.

Electromyography (EMG) is a useful modality for evaluating respiratory muscle activity and can be used to assess cough strength in patients with or without artificial airways. During voluntary coughing, EMG signals increase for the rectus, oblique, transverse abdominal, internal intercostal, and external anal sphincter muscles (66,67). EMG activity of the abdominal wall is related to cough flow, expired volume, and cough sound amplitude (137). However, EMG is a valuable diagnostic tool for patients with good motor function but reduced cough strength (66). It can effectively assess cough threshold and power in both healthy adults and individuals with spinal cord injuries (66,138). Compared to concentric needle electrodes, surface electrodes are better suited for obtaining accurate measurements of whole-muscle EMG activity (67).

Esophageal pressure varies with intrathoracic pressure; therefore, cough intensity is highly correlated with changes in esophageal pressure. Contraction of the abdominal muscles generates positive gastric pressure during coughing. Changes in internal gastric pressure, central venous pressure, bladder pressure, and rectal pressure are similar to those in esophageal pressure and also reflect cough strength, although small discrepancies exist among these parameters (34). These pressure-related indices can be used to assess cough strength in patients with or without artificial airways. Monitoring changes in pressure requires invasive catheterization, and the pressure sensor only functions correctly when the catheter is properly positioned.

Clearance and expectoration of mucus, including mucociliary transport, sputum weight (dry and wet), and sputum volume, are commonly used as primary or secondary outcomes in studies assessing the effectiveness of cough exercise tools (139). These measures also serve as supplementary indicators of cough ability. Current research shows that improved cough ability is often linked to increased sputum production (all P<0.05) (140). Measuring sputum volume at a single time point has inherent limitations and may not fully capture the patient overall cough capacity. To address this, dynamic observation over a specific time frame may be needed to assess sputum output as a measure of cough capacity. Additionally, due to individual variability, improvements in cough ability should be evaluated by comparing each patient’s performance before and after the intervention.

Most available data on assessing cough strength focus on healthy individuals or well-defined groups, such as the elderly, intubated patients, and those with neuromuscular disorders. However, clinical data remain limited for patients with glottic insufficiency or dysphagia after extubation.

Cough exercises

Given the consequences of weak cough, timely and early training in cough and expectoration is essential for patients at high risk of cough decline, as well as for those who already have reduced cough strength. Increased cough strength can enhance lung function and improve outcomes (29,141-143) (Table 4). Although various methods exist for cough training in critically ill patients, all are based on three fundamental principles: increasing inhaled volume, increasing expiratory flow, and oscillation (144). Commonly used methods for cough exercises are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5

| Principles | Breath-stacking | IS | Early mobilization | RMT | FES/TENS | NIV | VCM | IPPB | OPEP* | FET | ACBT | AD | MI-E | Vibration and percussion | HFWCO | IPV | MetaNeb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increase inhaled volume | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Increase expiratory flow | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||||||

| Airway oscillation | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

OPEP* including PEP bottle, PEP-Mask, Thera-PEP, Acapella, Flutter, RC Cornet, Aerobike, et al. IS, incentive spirometer; RMT, respiratory muscle training; FES, functional electrical stimulation; TENS, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; NIV, noninvasive ventilation; VCM, volumetric cough mode; IPPB, intermittent positive pressure breath; OPEP, oscillating positive expiratory pressure; FET, forced expiratory technology; ACBT, active cycle breath technology; AD, autogenic drainage; MI-E, mechanical insufflation-exsufflation; HFCWO, high frequency chest wall oscillation; IPV, intrapulmonary percussion ventilation.

Increase inhaled volume

Inhaled volume is the most important indicator of respiratory health in adult patients with either a single or continuous cough (86,90,145). Furthermore, maximum inspiratory pressure is more significantly associated with cough strength than maximum expiratory pressure for both voluntary and involuntary coughs. Therefore, increasing inspiratory muscle strength and inspiratory volume is essential for enhancing cough strength (70). Intermittent positive pressure breathing (91), NIV (80), and continuous positive airway pressure (85,122) can all passively increase inhaled volume and are effective. Some home ventilators can achieve these effects effectively (70). Voluntary exercise tools, such as the incentive spirometer (IS), have been shown to significantly increase maximum inspiratory capacity in both hospitalized and discharged patients (104,146-148). Notably, the effectiveness of the IS largely depends on the patient’s effort, and the addition of a reminder bell can lead to significant improvements (49,82,149). Additionally, it is important to avoid the adverse consequences of excessive use (150). Early mobilization, inspiratory muscle strength training, and certain forms of electrical muscle stimulation (94,136) can also improve inhaled volume in critically ill patients, as well as in those with neuromuscular diseases and postoperative patients (79,81,84,151). The inhaled volume of patients receiving mechanical ventilation can be increased by augmenting the conveying volume through the volumetric cough mode of the ventilator, thereby gradually raising the inhaled volume to provide a convenient target for the patient (49).

Increase expiratory flow

Exercising the expiratory muscles can effectively increase expiratory flow and improve cough capacity, particularly in patients with neuromuscular diseases (92,96,99-103,105,106,108,115,116,123,124). Setting resistance during the expiratory phase through positive expiratory pressure therapy can achieve a similar effect to PEEP for training the expiratory muscles (87,117,119,144). Different devices have specific requirements for patients during use; for example, the patient must be in either an upright or sitting position when using a flutter device (68,83,109). Some cough training methods, such as forced expiratory technology, active cycle of breathing techniques (134), autogenic drainage (69), and mechanical insufflation-exsufflation (72,73,78,111,120,129), can enhance both inspiratory volume and expiratory flow, thereby increasing expectoration and facilitating the expulsion of sputum (152,153). Despite insufficient evidence, mechanical insufflation-exsufflation is commonly used in patients with neuromuscular diseases to aid expectoration (154). Expiratory muscle training can also enhance muscle strength and cough capacity (125,126,131-133,155), and it seems to be more effective for improving CPF compared to inspiratory muscle training (113). In addition to mechanical aids, manual aids can also facilitate increased expiratory airflow, including expiratory rib cage compression (98), manual chest compression (114), expiratory flow acceleration (118) and abdominal wall compression, among others (71,76,77,88,89,127,128,135).

Oscillation

Oscillations in the airway or external to the chest wall can effectively transmit to the airway to facilitate sputum release (156). High-frequency oscillation can effectively increase tidal volume and inspiration duration, reduce respiratory rate, and result in deeper and slower breaths (95,97,110,121,130,157). Consequently, mean PEF will be greater (74). Commonly used techniques in the ICU include clapping and vibration, oscillating positive expiratory pressure (OPEP) (112), high-frequency chest wall oscillation (75), and intrapulmonary percussion ventilation (IPV) (158-162). Aside from IPV, there is no significant difference in the use of these devices; however, IPV is more effective and beneficial for airway clearance (160,163). The MetaNeb® System (Hill-Rom Holdings, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was recently introduced for the mobilization of secretions, lung expansion therapy, and the treatment and prevention of pulmonary atelectasis (164).

All of the above-mentioned means and methods of improving cough ability are not strictly contraindicated. All airway clearance techniques have a good safety profile when the patient is generally stable (139). For patients who can cooperate and have good compliance, they can take tools or methods with high autonomy to exercise, such as IS, OPEP, etc. If the patient is difficult to cooperate or has poor compliance, it would be more suitable for these patients to receive passive expectoration methods, such as IPV, MI-E, airway suction, etc. (93).

Currently, cough exercises are widely used in clinical practice; however, optimal effects are often not achieved because most of these techniques maintain rather than improve patient status (107,165). Cough exercises should be encouraged for critically ill patients; however, many do not tolerate prolonged training, necessitating the presence of a respiratory therapist or physical therapist. Furthermore, there is a lack of high-quality evidence regarding the appropriate power, frequency, and duration for cough exercises in critically ill patients (144,166). Therefore, further research is warranted to develop individualized training methods and parameters, as well as to enhance patients' tolerance and cooperation.

Conclusions

Weak cough in critically ill patients is linked to an increased risk of extubation failure, prolonged mechanical ventilation, longer ICU and hospital stays, and higher mortality. Therefore, it is crucial to select appropriate methods for assessing and exercising cough strength in ICU patients. CPF/PEF, SCSS, and WCT are relatively simple and widely used methods. The key elements of cough exercises typically include increasing inhaled volume, enhancing expiratory flow, and incorporating oscillation. Developing personalized programs and effective action plans is essential for cough exercises which largely depends on patient cooperation and persistence.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1673/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1673/prf

Funding: This study was financially supported by grants from

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-1673/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Van der Schans CP. Bronchial mucus transport. Respir Care 2007;52:1150-6; discussion 1156-8.

- Fernando SM, Tran A, Sadeghirad B, et al. Noninvasive respiratory support following extubation in critically ill adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med 2022;48:137-47. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hernández G, Vaquero C, Ortiz R, et al. Benefit with preventive noninvasive ventilation in subgroups of patients at high-risk for reintubation: a post hoc analysis. J Intensive Care 2022;10:43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duan J, Zhang X, Song J. Predictive power of extubation failure diagnosed by cough strength: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2021;25:357. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thille AW, Richard JC, Brochard L. The decision to extubate in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:1294-302. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thille AW, Boissier F, Ben Ghezala H, et al. Risk factors for and prediction by caregivers of extubation failure in ICU patients: a prospective study. Crit Care Med 2015;43:613-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Epstein SK, Ciubotaru RL. Independent effects of etiology of failure and time to reintubation on outcome for patients failing extubation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:489-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rothaar RC, Epstein SK. Extubation failure: magnitude of the problem, impact on outcomes, and prevention. Curr Opin Crit Care 2003;9:59-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sanson G, Sartori M, Dreas L, et al. Predictors of extubation failure after open-chest cardiac surgery based on routinely collected data. The importance of a shared interprofessional clinical assessment. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2018;17:751-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Esteban A, Anzueto A, Frutos F, et al. Characteristics and outcomes in adult patients receiving mechanical ventilation: a 28-day international study. JAMA 2002;287:345-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- 2-month mortality and functional status of critically ill adult patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation. Chest 2002;121:549-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Terzi N, Guerin C, Gonçalves MR. What's new in management and clearing of airway secretions in ICU patients? It is time to focus on cough augmentation. Intensive Care Med 2019;45:865-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morice AH, Fontana GA, Belvisi MG, et al. ERS guidelines on the assessment of cough. Eur Respir J 2007;29:1256-76. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee PC, Cotterill-Jones C, Eccles R. Voluntary control of cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2002;15:317-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Su WL, Chen YH, Chen CW, et al. Involuntary cough strength and extubation outcomes for patients in an ICU. Chest 2010;137:777-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Addington WR, Stephens RE, Phelipa MM, et al. Intra-abdominal pressures during voluntary and reflex cough. Cough 2008;4:2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ward K, Seymour J, Steier J, et al. Acute ischaemic hemispheric stroke is associated with impairment of reflex in addition to voluntary cough. Eur Respir J 2010;36:1383-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Enrichi C, Zanetti C, Gregorio C, et al. The assessment of the peak of reflex cough in subjects with acquired brain injury and tracheostomy and healthy controls. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 2020;274:103356. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lasserson D, Mills K, Arunachalam R, et al. Differences in motor activation of voluntary and reflex cough in humans. Thorax 2006;61:699-705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mills C, Jones R, Huckabee ML. Measuring voluntary and reflexive cough strength in healthy individuals. Respir Med 2017;132:95-101. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mootassim-Billah S, Van Nuffelen G, Schoentgen J, et al. Assessment of cough in head and neck cancer patients at risk for dysphagia-An overview. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 2021;4:e1395. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smina M, Salam A, Khamiees M, et al. Cough peak flows and extubation outcomes. Chest 2003;124:262-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gao XJ, Qin YZ. A study of cough peak expiratory flow in predicting extubation outcome. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2009;21:390-3.

- Beuret P, Roux C, Auclair A, et al. Interest of an objective evaluation of cough during weaning from mechanical ventilation. Intensive Care Med 2009;35:1090-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SC, Kang SW, Kim MT, et al. Correlation between voluntary cough and laryngeal cough reflex flows in patients with traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2013;94:1580-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan L, Zhao Q, Liu Y, et al. Semiquantitative cough strength score and associated outcomes in noninvasive positive pressure ventilation patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2014;108:1801-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duan J, Liu J, Xiao M, et al. Voluntary is better than involuntary cough peak flow for predicting re-intubation after scheduled extubation in cooperative subjects. Respir Care 2014;59:1643-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duan J, Zhou L, Xiao M, et al. Semiquantitative cough strength score for predicting reintubation after planned extubation. Am J Crit Care 2015;24:e86-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulnik ST, Birring SS, Hodsoll J, et al. Higher cough flow is associated with lower risk of pneumonia in acute stroke. Thorax 2016;71:474-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gobert F, Yonis H, Tapponnier R, et al. Predicting Extubation Outcome by Cough Peak Flow Measured Using a Built-in Ventilator Flow Meter. Respir Care 2017;62:1505-19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KK, Matos S, Ward K, et al. Sound: a non-invasive measure of cough intensity. BMJ Open Respir Res 2017;4:e000178. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Umayahara Y, Soh Z, Sekikawa K, et al. Estimation of Cough Peak Flow Using Cough Sounds. Sensors (Basel) 2018;18:2381. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Umayahara Y, Soh Z, Sekikawa K, et al. A Mobile Cough Strength Evaluation Device Using Cough Sounds. Sensors (Basel) 2018;18:3810. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aguilera LG, Gallart L, Álvarez JC, et al. Rectal, central venous, gastric and bladder pressures versus esophageal pressure for the measurement of cough strength: a prospective clinical comparison. Respir Res 2018;19:191. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sohn D, Park GY, Koo H, et al. Determining Peak Cough Flow Cutoff Values to Predict Aspiration Pneumonia Among Patients With Dysphagia Using the Citric Acid Reflexive Cough Test. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2018;99:2532-2539.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim AS, Aly MG, Abdel-Rahman KA, et al. Semi-quantitative Cough Strength Score as a Predictor for Extubation Outcome in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Prospective Observational Study. Neurocrit Care 2018;29:273-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morrow BM, Angelil L, Forsyth J, et al. The utility of using peak expiratory flow and forced vital capacity to predict poor expiratory cough flow in children with neuromuscular disorders. S Afr J Physiother 2019;75:1296. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norisue Y, Santanda T, Nabeshima T, et al. Association of Diaphragm Movement During Cough, as Assessed by Ultrasonography, With Extubation Outcome. Respir Care 2021;66:1713-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Froutan R, Abedini M, Bagheri Moghaddam A, et al. Comparison of “cough peak expiratory flow measurement” and “cough strength measurement using the white card test” in extubation success: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2020;25:52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O'Neill MP, Gopalan PD. Endotracheal tube cuff pressure change: Proof of concept for a novel approach to objective cough assessment in intubated critically ill patients. Heart Lung 2020;49:181-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chang S, Zhou K, Wang Y, et al. Prognostic Value of Preoperative Peak Expiratory Flow to Predict Postoperative Pulmonary Complications in Surgical Lung Cancer Patients. Front Oncol 2021;11:782774. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Norisue Y, Santanda T, Homma Y, et al. Ultrasonographic Assessment of Passive Cephalic Excursion of Diaphragm During Cough Expiration Predicts Cough Peak Flow in Healthy Adults. Respir Care 2019;64:1371-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonny V, Joffre J, Gabarre P, et al. Sonometric assessment of cough predicts extubation failure: SonoWean—a proof-of-concept study. Critical Care 2023;27:368. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee KW, Kim SB, Lee JH, et al. Cut-Off Value of Voluntary Peak Cough Flow in Patients with Parkinson's Disease and Its Association with Severe Dysphagia: A Retrospective Pilot Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023;59:921. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tabor Gray L, Donohue C, Vasilopoulos T, et al. Maximum Phonation Time as a Surrogate Marker for Airway Clearance Physiologic Capacity and Pulmonary Function in Individuals With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Speech Lang Hear Res 2023;66:1165-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Recasens BB, Balañá Corberó A, Llorens JMM, et al. Sound-based cough peak flow estimation in patients with neuromuscular disorders. Muscle Nerve 2024;69:213-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulnik ST, Lewko A, MacBean V, et al. Accuracy in the Assessment of Cough Peak Flow: Good Progress for a "Work in Progress". Respir Care 2020;65:133-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Winck JC, LeBlanc C, Soto JL, et al. The value of cough peak flow measurements in the assessment of extubation or decannulation readiness. Rev Port Pneumol (2006) 2015;21:94-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Del Amo Castrillo L, Lacombe M, Boré A, et al. Comparison of Two Cough-Augmentation Techniques Delivered by a Home Ventilator in Subjects With Neuromuscular Disease. Respir Care 2019;64:255-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi J, Baek S, Kim G, et al. Peak Voluntary Cough Flow and Oropharyngeal Dysphagia as Risk Factors for Pneumonia. Ann Rehabil Med 2021;45:431-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulnik ST, MacBean V, Birring SS, et al. Accuracy of portable devices in measuring peak cough flow. Physiol Meas 2015;36:243-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bai L, Duan J. Use of Cough Peak Flow Measured by a Ventilator to Predict Re-Intubation When a Spirometer Is Unavailable. Respir Care 2017;62:566-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Almeida CM, Lopes AJ, Guimarães FS. Cough peak flow to predict the extubation outcome: Comparison between three cough stimulation methods. Can J Respir Ther 2020;56:58-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaneko H, Suzuki A, Horie J. Relationship of Cough Strength to Respiratory Function, Physical Performance, and Physical Activity in Older Adults. Respir Care 2019;64:828-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang SW, Shin JC, Park CI, et al. Relationship between inspiratory muscle strength and cough capacity in cervical spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord 2006;44:242-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thille AW, Boissier F, Muller M, et al. Role of ICU-acquired weakness on extubation outcome among patients at high risk of reintubation. Crit Care 2020;24:86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khamiees M, Raju P, DeGirolamo A, et al. Predictors of extubation outcome in patients who have successfully completed a spontaneous breathing trial. Chest 2001;120:1262-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Duan J, Zhou L, Xiao M, et al. Semiquantitative cough strength score for predicting reintubation after planned extubation. Am J Crit Care 2015;24:e86-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hong Y, Deng M, Hu W, et al. Weak cough is associated with increased mortality in COPD patients with scheduled extubation: a two-year follow-up study. Respir Res 2022;23:166. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haaksma ME, Smit JM, Boussuges A, et al. EXpert consensus On Diaphragm UltraSonography in the critically ill (EXODUS): a Delphi consensus statement on the measurement of diaphragm ultrasound-derived parameters in a critical care setting. Crit Care 2022;26:99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kilaru D, Panebianco N, Baston C. Diaphragm Ultrasound in Weaning From Mechanical Ventilation. Chest 2021;159:1166-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stephens RE, Addington WR, Miller SP, et al. Videofluoroscopy of the diaphragm during voluntary and reflex cough in humans. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2003;82:384. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vivier E, Mekontso Dessap A, Dimassi S, et al. Diaphragm ultrasonography to estimate the work of breathing during non-invasive ventilation. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:796-803. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Goligher EC, Fan E, Herridge MS, et al. Evolution of Diaphragm Thickness during Mechanical Ventilation. Impact of Inspiratory Effort. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;192:1080-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santana PV, Cardenas LZ, Albuquerque ALP, et al. Diaphragmatic ultrasound: a review of its methodological aspects and clinical uses. J Bras Pneumol 2020;46:e20200064. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Macedo FS, da Rocha AF, Miosso CJ, et al. Use of electromyographic signals for characterization of voluntary coughing in humans with and without spinal cord injury-A systematic review. Physiother Res Int 2019;24:e1761. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deffieux X, Hubeaux K, Porcher R, et al. External intercostal muscles and external anal sphincter electromyographic activity during coughing. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2008;19:521-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakamura S, Kawakami M. Acute effect of use of the Flutter on expectoration of sputum in patients with chronic respiratory diseases. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi 1996;34:180-5.

- Savci S, Ince DI, Arikan H. A comparison of autogenic drainage and the active cycle of breathing techniques in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 2000;20:37-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Toussaint M, Pernet K, Steens M, et al. Cough Augmentation in Subjects With Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: Comparison of Air Stacking via a Resuscitator Bag Versus Mechanical Ventilation. Respir Care 2016;61:61-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berney S, Denehy L, Pretto J. Head-down tilt and manual hyperinflation enhance sputum clearance in patients who are intubated and ventilated. Aust J Physiother 2004;50:9-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Winck JC, Gonçalves MR, Lourenço C, et al. Effects of mechanical insufflation-exsufflation on respiratory parameters for patients with chronic airway secretion encumbrance. Chest 2004;126:774-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sancho J, Servera E, Díaz J, et al. Efficacy of mechanical insufflation-exsufflation in medically stable patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Chest 2004;125:1400-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McCarren B, Alison JA. Physiological effects of vibration in subjects with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2006;27:1204-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lange DJ, Lechtzin N, Davey C, et al. High-frequency chest wall oscillation in ALS: an exploratory randomized, controlled trial. Neurology 2006;67:991-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Spivak E, Keren O, Niv D, et al. Electromyographic signal-activated functional electrical stimulation of abdominal muscles: the effect on pulmonary function in patients with tetraplegia. Spinal Cord 2007;45:491-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Durmuş D, Alayli G, Uzun O, et al. Effects of two exercise interventions on pulmonary functions in the patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine 2009;76:150-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chatwin M, Simonds AK. The addition of mechanical insufflation/exsufflation shortens airway-clearance sessions in neuromuscular patients with chest infection. Respir Care 2009;54:1473-9.

- Barros GF. Treinamento muscular respiratório na revascularização do miocárdio. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Cardiovascular 2010;25:483-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Neligan PJ, Malhotra G, Fraser M, et al. Noninvasive ventilation immediately after extubation improves lung function in morbidly obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea undergoing laparoscopic bariatric surgery. Anesth Analg 2010;110:1360-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sutbeyaz ST, Koseoglu F, Inan L, et al. Respiratory muscle training improves cardiopulmonary function and exercise tolerance in subjects with subacute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2010;24:240-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pangborn J, Kazemi L, Eltorai AEM. Human factors and usability of an incentive spirometer patient reminder (SpiroTimer). Adv Respir Med 2020;88:574-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chicayban LM, Zin WA, Guimarães FS. Can the Flutter Valve improve respiratory mechanics and sputum production in mechanically ventilated patients? A randomized crossover trial. Heart Lung 2011;40:545-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matheus GB, Dragosavac D, Trevisan P, et al. Postoperative muscle training improves tidal volume and vital capacity in the postoperative period of CABG surgery. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Cardiovascular 2012;27:362-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nery FP, Lopes AJ, Domingos DN, et al. CPAP increases 6-minute walk distance after lung resection surgery. Respir Care 2012;57:363-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cleary S, Misiaszek JE, Kalra S, et al. The effects of lung volume recruitment on coughing and pulmonary function in patients with ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener 2013;14:111-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Venturelli E, Crisafulli E, DeBiase A, et al. Efficacy of temporary positive expiratory pressure (TPEP) in patients with lung diseases and chronic mucus hypersecretion. The UNIKO(R) project: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2013;27:336-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McBain RA, Boswell-Ruys CL, Lee BB, et al. Abdominal muscle training can enhance cough after spinal cord injury. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2013;27:834-43. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim J, Park JH, Yim J. Effects of respiratory muscle and endurance training using an individualized training device on the pulmonary function and exercise capacity in stroke patients. Med Sci Monit 2014;20:2543-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mellies U, Goebel C. Optimum insufflation capacity and peak cough flow in neuromuscular disorders. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2014;11:1560-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lacombe M, Del Amo Castrillo L, Boré A, et al. Comparison of three cough-augmentation techniques in neuromuscular patients: mechanical insufflation combined with manually assisted cough, insufflation-exsufflation alone and insufflation-exsufflation combined with manually assisted cough. Respiration 2014;88:215-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulnik ST, Rafferty GF, Birring SS, et al. A pilot study of respiratory muscle training to improve cough effectiveness and reduce the incidence of pneumonia in acute stroke: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:123. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Li Y, He W, et al. The application of fibrobronchoscopy in extubation for patients suffering from acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with low cough peak expiratory flow. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2014;26:855-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tokuda M, Tabira K, Masuda T, et al. Effect of modulated-frequency and modulated-intensity transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation after abdominal surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain 2014;30:565-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Esguerra-Gonzales A, Ilagan-Honorio M, Kehoe P, et al. Effect of high-frequency chest wall oscillation versus chest physiotherapy on lung function after lung transplant. Appl Nurs Res 2014;27:59-66. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Aslan GK, Gurses HN, Issever H, et al. Effects of respiratory muscle training on pulmonary functions in patients with slowly progressive neuromuscular disease: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2014;28:573-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Amelina EL, Krasovskii SA, Usacheva MV, et al. Use of high-frequency chest wall oscillation in an exacerbation of chronic pyo-obstructive bronchitis in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Ter Arkh 2014;86:33-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guimarães FS, Lopes AJ, Constantino SS, et al. Expiratory Rib Cage Compression in Mechanically Ventilated Subjects: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Respiratory Care 2014;59:678-685. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liao LY, Chen KM, Chung WS, et al. Efficacy of a respiratory rehabilitation exercise training package in hospitalized elderly patients with acute exacerbation of COPD: a randomized control trial. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2015;10:1703-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Postma K, Vlemmix LY, Haisma JA, et al. Longitudinal association between respiratory muscle strength and cough capacity in persons with spinal cord injury: An explorative analysis of data from a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med 2015;47:722-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kulnik ST, Birring SS, Moxham J, et al. Does respiratory muscle training improve cough flow in acute stroke? Pilot randomized controlled trial. Stroke 2015;46:447-53. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reyes A, Cruickshank T, Nosaka K, et al. Respiratory muscle training on pulmonary and swallowing function in patients with Huntington's disease: a pilot randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2015;29:961-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeren M, Demir R, Yigit Z, et al. Effects of inspiratory muscle training on pulmonary function, respiratory muscle strength and functional capacity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil 2016;30:1165-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi JY, Rha DW, Park ES. Change in Pulmonary Function after Incentive Spirometer Exercise in Children with Spastic Cerebral Palsy: A Randomized Controlled Study. Yonsei Med J 2016;57:769-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tallner A, Streber R, Hentschke C, et al. Internet-Supported Physical Exercise Training for Persons with Multiple Sclerosis-A Randomised, Controlled Study. Int J Mol Sci 2016;17:1667. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hegland KW, Davenport PW, Brandimore AE, et al. Rehabilitation of Swallowing and Cough Functions Following Stroke: An Expiratory Muscle Strength Training Trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:1345-51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SM, Choi WA, Won YH, et al. A Comparison of Cough Assistance Techniques in Patients with Respiratory Muscle Weakness. Yonsei Med J 2016;57:1488-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jo MR, Kim NS. The correlation of respiratory muscle strength and cough capacity in stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci 2016;28:2803-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dwyer TJ, Zainuldin R, Daviskas E, et al. Effects of treadmill exercise versus Flutter(R) on respiratory flow and sputum properties in adults with cystic fibrosis: a randomised, controlled, cross-over trial. BMC Pulm Med 2017;17:14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nicolini A, Grecchi B, Ferrari-Bravo M, et al. Safety and effectiveness of the high-frequency chest wall oscillation vs intrapulmonary percussive ventilation in patients with severe COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018;13:617-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jung JH, Oh HJ, Lee JW, et al. Improvement of Peak Cough Flow After the Application of a Mechanical In-exsufflator in Patients With Neuromuscular Disease and Pneumonia: A Pilot Study. Ann Rehabil Med 2018;42:833-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li P, Lai Y, Zhou K, et al. Can Perioperative Oscillating Positive Expiratory Pressure Practice Enhance Recovery in Lung Cancer Patients Undergoing Thorascopic Lobectomy? Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi 2018;21:890-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Reyes A, Castillo A, Castillo J, et al. The effects of respiratory muscle training on peak cough flow in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled study. Clinical Rehabilitation 2018;32:1317-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oliveira ACO, Lorena DM, Gomes LC, et al. Effects of manual chest compression on expiratory flow bias during the positive end-expiratory pressure-zero end-expiratory pressure maneuver in patients on mechanical ventilation. J Bras Pneumol 2019;45:e20180058. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jang KW, Lee SJ, Kim SB, et al. Effects of mechanical inspiration and expiration exercise on velopharyngeal incompetence in subacute stroke patients. J Rehabil Med 2019;51:97-102. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alves WM, Alves TG, Ferreira RM, et al. Strength training improves the respiratory muscle strength and quality of life of elderly with Parkinson disease. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2019;59:1756-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xavier VB, Avanzi O, de Carvalho BDMC, et al. Combined aerobic and resistance training improves respiratory and exercise outcomes more than aerobic training in adolescents with idiopathic scoliosis: a randomised trial. J Physiother 2020;66:33-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Riboldazzi G, Spinazza G, Beccarelli L, et al. Effectiveness of expiratory flow acceleration in patients with Parkinson's disease and swallowing deficiency: A preliminary study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2020;199:106249. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sundar KM, Willis AM, Smith S, et al. A Randomized, Controlled, Pilot Study of CPAP for Patients with Chronic Cough and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Lung 2020;198:449-57. [Crossref] [PubMed]