From self-awareness to self-actualization: empowering sepsis survivors to a meaningful and enduring recovery

The rising incidence of sepsis and improvements in critical care medicine have led to a growing number of sepsis survivors (1). Unfortunately, many intensive care unit (ICU) survivors suffer impairments in cognitive function, physical function and mental health (2-5). In 2010, these revelations received a name, post-intensive care syndrome (PICS) (6). PICS is thought to cause, or contribute to, loss of employment, reduced health-related quality of life, and increased healthcare utilization (7-9). Given the impact on survivors and society, efforts to improve the quality and quantity of life among sepsis survivors are urgently needed.

On the heels of the stakeholder conference that coined the term PICS, Schmidt and colleagues launched an innovative multi-center, unblinded, randomized clinical trial in the out-patient setting. “Sepsis survivors monitoring and coordination in outpatient health care” (SMOOTH) focused on determining if a primary-care based intervention would improve long-term outcomes of sepsis survivors, and mental health-related quality of life specifically (10). Between 2011 and 2014, 291 adult sepsis survivors from nine ICUs in Germany were randomized to a usual care (the primary care group) or a 12-month intervention group.

The intervention involved three components: (I) discharge management with structured information between the inpatient and outpatient providers; (II) training patients and primary care physicians in sepsis sequelae and self-monitoring of PICS-related symptoms and functional abilities, nutrition, sleep habits, and pain; and (III) telephone monitoring of patients for 12 months (11). The intervention was delivered by one of three case managers who were nurses with ICU experience who underwent training in outpatient case management focused on sepsis, sepsis sequelae, communication skills, telephone monitoring, and goal setting. One of three liaison physicians was responsible for overseeing the case manager and communicating any results from the telephone monitoring to the primary care physician and offering consultation, training and clinical decision support as necessary. Together, as depicted in image e3, these interactions made for an interdependent relationship between the case manager, consulting physician, primary care physician, and patient.

At the time of the trial design, PICS recognition was emerging and survivors were beginning to share their stories. Survivors of critical illness expressed that they were ill-prepared and ill-equipped for the “day-to-day impact of new disability” (12). As a result, PICS defined one’s “sense of self”, led to strain on existing relationships, and effective coping skills were identified as essential to survive life after critical illness. Together, an intervention that prioritized awareness of functional impairments incurred after critical illness and coping skill-training was an evidence-based intervention worthy of examination at the time the trial began enrolling.

With this background, the intervention began with the case manager having a 60-minute face-to-face training session with the patient shortly after ICU discharge that focused on sepsis sequelae. Specifically, sepsis sequelae focused on the “Sepsis Six”, which aligned with PICS and included: cognitive impairment, pain, PTSD, cachexia, depression, and physical impairment. Notably, clinical manifestations of sepsis-induced immunosuppression (e.g., recurrent infection), sepsis-induced inflammation and cardiovascular risk (e.g., atrial fibrillation), identified after the trial began (13), were not incorporated into the SMOOTH educational materials or self-monitoring programs.

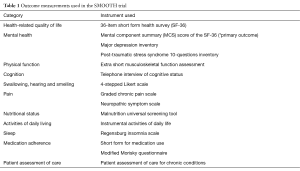

This initial visit was followed by monthly telephone contact for the first 6 months, then every 3 months to complete the year. Case managers used validated tools to assess cognition, physical function, mental health, sleep, nutritional status, pain, and process outcomes at ICU discharge as well as 6 and 12 months (Table 1). In addition to the validated tools, data on process-related outcomes were also derived from primary care physician documentation, including number of primary care physician contacts, number of specialty contacts, number of diagnostic procedures, days unable to work, length of stay in the hospital and rehabilitation center, and need for therapeutic aids.

Full table

The primary outcome was the change in mental health-related quality of life between ICU discharge and 6-month using the mental component summary (MCS) score of the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36). The primary aim of the study was to detect a difference of 5 points or more in the mean MCS score, a clinically meaningful difference.

A total of 291 patients were enrolled, with 143 randomized to usual care and 148 randomized to the intervention. Overall, baseline characteristics were well balanced. The mean age of study participants was 61.6 years and 66% of study participants were male. The majority of participants developed sepsis from a nosocomial infection while 36% had community-acquired infections. The median length of stay in the ICU was 26 days and 84.4% were mechanically ventilated for a median duration of 12 days. Within the intervention group, 130 (87.8%) received patient training from case managers at a median of 8 days after ICU discharge, and 84.5% of primary care physicians received training from the liaison physician at a mean of 62 days after the patient was discharged from the ICU. The delay in PCP training is potentially meaningful, as more recent evidence has revealed that as many as one out of four sepsis survivors will be rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge, the majority with another life-threatening infection (13).

At 6 months, 72 patients (24.7%) died or were lost to follow-up, leaving 219 patients in the primary analyses. There was no significant difference in the mean change of the MCS score between the intervention group (3.79 points, 95% CI: 1.05–6.54) and the usual care group (2.15 points, 95% CI: −1.79 to 6.09, P=0.28). A total of 202 patients completed follow-up at 12 months (30.6% died or were lost to follow-up). There was also no significant difference in the mean change of the MCS score between the intervention and usual care groups at 12 months. The authors additionally evaluated over 60 secondary outcomes at 6 and 12 months. There were no statistically significant differences in the eight subscales of the SF-36, depressive symptoms, post-traumatic stress symptoms, or cognitive function. There were also no differences in process-related outcomes including days unable to work, number of primary care physician contacts and number of specialty referrals.

However, a signal of the potential benefits of the self-management aspect of the intervention, patients in the intervention group had better functional outcomes that were within the range considered to be clinically meaningful differences. Patients in the intervention group scored one point higher (less impairment) on the Activities of Daily Living assessment at 6 (P=0.03) and 12 months (P=0.05), and 9 fewer points (less impairment) on the Short Musculoskeletal Function Assessment physical function assessment at 6 months (P=0.04), and 9–10 fewer points (less disability) on the Short Musculoskeletal Function assessment disability assessment at 6 (P=0.03) and 12 months (P=0.06).

There are several limitations of the present study that are worth highlighting. First, study participants were limited to ICU survivors, thereby capturing a more severely ill subgroup of sepsis survivors. Further, those enrolled had longer ICU stays and longer duration of mechanical ventilation compared to many other studies of similar patient populations (3,7,14). This may have caused an ascertainment bias because patients with longer ICU stays may have been easier to identify for enrollment, may have made it more difficult to demonstrate a benefit with the intervention, and may not be generalizable. The study also excluded patients with significant cognitive impairment, patients who are particularly vulnerable and may be most likely to benefit from the intervention. Second, although the study used several well-validated tools to assess the many domains that are impaired in ICU survivors, in the absence of consensus on the best tools to use in post-ICU outcomes research, comparison across studies is inherently challenging (15). Additionally, the study was not designed to investigate whether the intervention had any effect on hospital readmissions, a challenge faced by nearly one out of four sepsis survivors (16). Finally, although the broad intervention in some ways is a strength of the study, it could have been too broad to significantly impact individual domains. Although the ultimate goal is to improve all the domains that are impaired in ICU survivors, these impairments may not track completely with one another. Some patients may predominantly experience cognitive impairment, while others predominantly suffer psychiatric impairment or functional impairment. An alternative strategy would be to target specific functional disabilities. Then, armed with evidence-based interventions that improve specific domains, we could combine them into a bundle for patients with impairments across multiple domains or use a more targeted approach.

In conclusion, as the sepsis survivorship literature has evolved (13), so too has our understanding of what survivors experience and therefore what they need to survive and thrive in the long-term. Education, awareness, preparation, and coordination of care remain the pillars upon which to build a “culture of resilience” amongst sepsis survivors (17), yet they are not sufficient. Innovative strategies, such as peer-to-peer survivor support, are needed to close the gap between what survivors crave and what they receive (18). Survivors yearn to salvage what they have and regain what was lost. To stave off new and recurrent/unresolved infections that plague many survivors, future efforts will need to incorporate sepsis surveillance strategies. To regain what survivors have lost, coping skills training will need to be paired with effective cognitive and physical rehabilitation (19-23), initiated early in the recovery process. Caregivers, in hindsight conspicuously absent from the conceptual diagram employed in SMOOTH, will need to be engaged in the recovery process (24). While SMOOTH reveals that self-awareness of life after sepsis is not sufficient to improve long-term outcomes, it sets the stage for efforts to achieve self-actualization through a process that prepares survivors to face, and overcome, the challenges that lie ahead after sepsis.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant F32-GM116637.

Footnote

Provenance: This is an invited Editorial commissioned by the Section Editor Zhongheng Zhang (Department of Critical Care Medicine, Jinhua Municipal Central Hospital, Jinhua Hospital of Zhejiang University, Jinhua, China).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Iwashyna TJ, Cooke CR, Wunsch H, et al. Population burden of long-term survivorship after severe sepsis in older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1070-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fan E, Dowdy DW, Colantuoni E, et al. Physical complications in acute lung injury survivors: a two-year longitudinal prospective study. Crit Care Med 2014;42:849-59. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, et al. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1306-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen ME, Christie JD, Lanken PN, et al. The adult respiratory distress syndrome cognitive outcomes study: long-term neuropsychological function in survivors of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;185:1307-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med 2011;39:371-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H, et al. Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders' conference. Crit Care Med 2012;40:502-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yende S, Austin S, Rhodes A, et al. Long-Term Quality of Life Among Survivors of Severe Sepsis: Analyses of Two International Trials. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1461-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oeyen SG, Vandijck DM, Benoit DD, et al. Quality of life after intensive care: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med 2010;38:2386-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Prescott HC, Langa KM, Liu V, et al. Increased 1-year healthcare use in survivors of severe sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:62-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt K, Worrack S, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of a Primary Care Management Intervention on Mental Health-Related Quality of Life Among Survivors of Sepsis: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;315:2703-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schmidt K, Thiel P, Mueller F, et al. Sepsis survivors monitoring and coordination in outpatient health care (SMOOTH): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2014;15:283. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cox CE, Docherty SL, Brandon DH, et al. Surviving critical illness: acute respiratory distress syndrome as experienced by patients and their caregivers. Crit Care Med 2009;37:2702-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maley JH, Mikkelsen ME. Short-term Gains with Long-term Consequences: The Evolving Story of Sepsis Survivorship. Clin Chest Med 2016;37:367-80. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brummel NE, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Delirium in the ICU and subsequent long-term disability among survivors of mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med 2014;42:369-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Turnbull AE, Rabiee A, Davis WE, et al. Outcome Measurement in ICU Survivorship Research From 1970 to 2013: A Scoping Review of 425 Publications. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1267-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sun A, Netzer G, Small DS, et al. Association Between Index Hospitalization and Hospital Readmission in Sepsis Survivors. Crit Care Med 2016;44:478-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maley JH, Mikkelsen ME. Sepsis survivorship: how can we promote a culture of resilience? Crit Care Med 2015;43:479-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen ME, Jackson JC, Hopkins RO, et al. Peer Support as a Novel Strategy to Mitigate Post-Intensive Care Syndrome. AACN Adv Crit Care 2016;27:221-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jackson JC, Ely EW, Morey MC, et al. Cognitive and physical rehabilitation of intensive care unit survivors: results of the RETURN randomized controlled pilot investigation. Crit Care Med 2012;40:1088-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones C, Eddleston J, McCairn A, et al. Improving rehabilitation after critical illness through outpatient physiotherapy classes and essential amino acid supplement: A randomized controlled trial. J Crit Care 2015;30:901-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, et al. Rehabilitation after critical illness: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2456-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brummel NE, Girard TD, Ely EW, et al. Feasibility and safety of early combined cognitive and physical therapy for critically ill medical and surgical patients: the Activity and Cognitive Therapy in ICU (ACT-ICU) trial. Intensive Care Med 2014;40:370-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chao PW, Shih CJ, Lee YJ, et al. Association of postdischarge rehabilitation with mortality in intensive care unit survivors of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;190:1003-11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cameron JI, Chu LM, Matte A, et al. One-Year Outcomes in Caregivers of Critically Ill Patients. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1831-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]