Demographics, risk factors and prevalence of chronic cough in Asian general adult population: a narrative review

Introduction

Cough is a vital protective reflex preventing aspiration and enhancing airway clearance (1,2). When cough was excessive and chronic, it brought a marked adverse effect on quality of life, major medical and socio-economic consequences (2-6).

The definition of chronic cough is diverse, which increases the challenge of comparing the prevalence of chronic cough in different populations. In 1965, the Medical Research Council defined chronic bronchitis as coughing with phlegm on most days during at least three consecutive months for more than two successive years (7). Based on this criterion, early studies defined chronic cough as lasting for at least 3 months. In 2006, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) cough guideline recommended defining chronic cough as lasting more than 8 weeks (8). Subsequently, the 2018 CHEST (9) and 2020 European Respiratory Society (ERS) cough guidelines (1) also accepted this definition. In addition, a study defined chronic cough without any objective duration, but rather rely on subjective judgment of whether the patients have longstanding cough (10).

Chronic cough is a major symptom of many diseases, and the most common conditions include asthma, cough variant asthma (CVA), upper airway cough syndrome (UACS) (termed postnasal drip syndrome previously), rhinitis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (11,12). Thus, the prevalence of symptomatic chronic cough may correlate with the prevalence of its common causes. However, there may be no obvious cause for chronic cough in more than half of the patients through survey questionnaire (4,11). Additionally, patients with refractory chronic cough (13), defined as coughing persists despite thorough assessment and optimal treatment of the underlying condition, or unexplained chronic cough (13,14) indicating either no underlying disease or etiology that can be identified commonly have increased cough reflex sensitivity, which has been described as cough hypersensitivity syndrome. Thus, epidemiologically, these undetected cases are much less obvious than symptomatic cough which suggested that the prevalence of chronic cough may be much higher.

The first anatomical diagnostic protocol for chronic cough was implemented by Irwin and colleagues (15) in 1981. A variety of investigations have been performed since then to determine the epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, treatment, and management of chronic cough worldwide. Asia has the largest population size, the unique cultures, lifestyles, environments, and genetic backgrounds among different countries and regions, which may be varied and distinct from those reported in other regions of the world.

The global prevalence of chronic cough was 9.6% in a pooled analysis by Song and colleagues (16). They also reported there was much lower prevalence of chronic cough for 4.4% in Asian countries compared to 18.1% in Oceania, 12.7% in Europe, and 11.0% in United States, showing a significant regional difference. And almost half of chronic cough patients (51.2%) did not use any medications indicating a poor treatment management (11). The most promising future developments in pharmacotherapy are drugs reducing hypersensitivity by neuromodulation such as the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) receptor (P2X3), which have early regulatory approval in Japan and a few other countries (17,18), also drawing attention to the epidemiology of chronic cough in Asia.

However, the prevalence, risk factors and disease burden of chronic cough in Asians have not undergone systematic analysis. Herein, we perform this narrative review to describe the prevalence of chronic cough in several geographical areas of Asia, and to summarize the underlying causes and burden among chronic cough patients. We present this article in accordance with the Narrative Review reporting checklist (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-248/rc).

Methods

The PubMed database, the Cochrane Library and Web of Science were searched from January 1, 2004 to January 1, 2024. The searching strategy included medical theme title as the main and supplemented by free text words covering “chronic cough”, “chronic bronchitis”, “longstanding cough”, “persistent cough”, “epidemiology”, “prevalence”, “risk factor”, “burden”, “adult”, “general population”, and “Asia”. Study designs included observational study design (case-control, cross-sectional, cohort), review, and meta-analysis articles. Studies published in English and conducted on humans were considered. Further details of the literature search are described in Table 1.

Table 1

| Items | Specification |

|---|---|

| Date of search | January 1, 2024 |

| Databases and other sources searched | The PubMed database, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science |

| Search terms used | Medical subject headings and free text words covering “chronic cough”, “chronic bronchitis”, “longstanding cough”, “persistent cough”, “epidemiology”, “prevalence”, “risk factor”, “burden”, “adult”, “general population”, and “Asia” |

| Timeframe | From January 1, 2004 to January 1, 2024 |

| Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria: observational study design (case-control, cross-sectional, cohort), review, meta-analysis, conducted on humans, English language only |

| Exclusion criteria: editorial, comments, letters, proceedings, case reports, full paper, non-English papers | |

| Selection process | X.Y. did the initial literature search with subsequent help from all authors |

Discussion

Prevalence and demographics

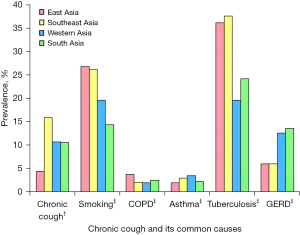

There have been different definitions of chronic cough, which have increased the challenge of comparing the chronic cough prevalence in different studies. According to the geographical subregions in Asia (Figure 1), we summarized the prevalence of chronic cough in different Asian countries or regions from recent studies (Table 2), and the prevalence of its most frequent potential causes based on Global Burden of Disease Study (GBD) (23,24) in Figure 2. Theoretically, the prevalence of chronic cough may correlate with the prevalence of common causes of symptomatic cough, i.e., smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, tuberculosis, and, GERD, however, the association between the prevalence of chronic cough and its common causes is not always evident, the reasons are complex and need further research.

Table 2

| First author, publication year | Study name | Country or region |

Study year |

Population | Sample size | Chronic cough definition | Chronic cough prevalence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Sex | Age | Smoking status | |||||||

| East Asia | ||||||||||

| Huang K, 2022 (5) | The CPH study | China | 2012–2015 | ≥20 years | 50,991 | Coughing last for >3 months each year | 3.6% | Women: 2.6%, men: 4.6% (P=0.0005) | 20–49 years: 2.4%, ≥50 years: 6.0% (P<0.0001) | Never: 2.5%, ever: 5.9% (P<0.0001) |

| Yu CJ, 2022 (6) | The 2020 China Taiwan NHWS and a chronic cough survey | Taiwan, China | 2020 | ≥18 years | 11,507 | Coughing last for ≥8 weeks in the past 12 months and currently at the time of survey | Lifetime: 8.27%; the 12-month: 5.55% | Lifetime: women: 8.38%, men: 8.15% (no P value reported). The 12-month: women: 5.86%, men: 5.23% (no P value reported) | • Lifetime: 18–29 years: 5.89%, 30–39 years: 8.12%, 40–49 years: 7.26%, 50–64 years: 7.55%, ≥65 years: 13.05% (no P value reported) | • Lifetime: never: 7.50%, former: 9.73%, current: 12.86% (no P value reported) |

| • The 12-month: 18–29 years: 3.73%, 30–39 years: 6.17%, 40–49 years: 4.73%, 50–64 years: 4.85%, ≥65 years: 8.74% (no P value reported) | • The 12-month: never: 5.01%, former: 6.64%, current: 8.76% (no P value reported) | |||||||||

| The 2020 South Korea NHWS and a chronic cough survey | South Korea | 2020 | ≥18 years | 12,660 | Coughing last for ≥8 weeks in the past 12 months and currently at the time of survey | Lifetime: 6.20%; the 12-month: 4.34% | Lifetime: women: 7.01%, men: 5.39% (no P value reported); the 12-month: women: 4.89%, men: 3.78% (no P value reported) | • Lifetime: 18–29 years: 5.16%, 30–39 years: 6.94%, 40–49 years: 5.28%, 50–64 years: 4.45%, ≥65 years: 10.22% (no P value reported); | • Lifetime: never: 5.68%, former: 5.48%, current: 8.19% (no P value reported) | |

| • The 12-month: 18–29 years: 3.80%, 30–39 years: 4.80%, 40–49 years: 3.78%, 50–64 years: 3.09%, ≥65 years: 6.96% (no P value reported) | • The 12-month: never: 3.87%, former: 3.71%, current: 6.12% (no P value reported) | |||||||||

| Kang MG, 2017 (19) | The KNHANES 2010–2012 | South Korea | 2010–2012 | ≥18 years | 18,071 | Coughing last for ≥8 weeks | 2.6% | Women: 2.0%, men: 3.3% (P<0.001) | NA | NA |

| Tobe K, 2021 (11) | The 2019 Japan NHWS and a chronic cough survey | Japan | 2019 | ≥20 years | 24,015 | Coughing last for >8 weeks in the past 12 months | 4.29% | NA | NA | NA |

| Southeast Asia | ||||||||||

| Lâm HT, 2011 (10) | A study in Hanoi and Bavi | Vietnam | 2007–2008 | 21–70 years | 5,782 (Hanoi: 2,115, Bavi: 3,667) | Coughing last longstanding during the last years | Hanoi: 12.0%; Bavi: 18.1% |

NA | NA | NA |

| Western Asia | ||||||||||

| Hamzaçebi H, 2006 (20) | The ECRHS | Turkey | 2002 | ≥15 years | 1,916 | Coughing on most days >3 months in the past 12 months |

10.6% | Women: 8.9%, men: 13.0% (P<0.01) | 15–29 years: 6.1%, 30–49 years: 9.9%, ≥50 years: 19.1% (P<0.0001) | Never: 6.9%, former: 9.2%, current: 17.8% (P<0.0001) |

| South Asia | ||||||||||

| Bishwajit G, 2017 (21) | The World Health Survey (2002–2003) | Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka | 2002 | ≥18 years | 35,929 (Bangladesh: 5,510, India: 9,495, Nepal: 8,579, Pakistan: 6,118, Sri Lanka: 6,227) | Coughing last for >3 weeks in the past 12 months | Bangladesh: 14.4%, India: 11%, Nepal: 15.3%, Pakistan: 10%, Sri Lanka: 5.9% | Bangladesh: women: 14.3%, men: 14.5% (no P value reported); India: women: 10.6%, men: 11.5% (no P value reported); Nepal: women: 15.4%, men: 15% (no P value reported); Pakistan: women: 8.4%, men: 11.2% (no P value reported); Sri Lanka: women: 5.3%, men: 6.5% (no P value reported) | NA | NA |

| Mahesh PA, 2011 (22) | A study in Mysore taluk | India | 2006–2009 | ≥30 years | 4,333 | Coughing firstly in the morning or at any time during the day or night >3 months each year | 2.5% | Women: 1.3%, men: 3.6% (no P value reported) | 31–40 years: 1.1%, 41–50 years: 2.2%, 51–60 years: 3.0%, 61–70 years: 4.3%, ≥71 years: 11.1% (no P value reported) | Never: 1.5%, ever: 5.0% (no P value reported) |

CPH, China Pulmonary Health; ECRHS, European Community Respiratory Health Survey; KNHANES, Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; NA, not available; NHWS, National Health and Wellness Survey.

East Asia

In China, a meta-analysis included 15 studies involving 141,114 community-based adults showed a prevalence of chronic cough was 6.22%, with 4.38% in southern China and 8.70% in northern China (25). Nonetheless, the actual prevalence of chronic cough in China might not be accurately reflected due to the small sample sizes of the studies in this pooled analysis, and the diagnostic criteria and sampling methods were different. The China Pulmonary Health (CPH) was a national cross-sectional study that enrolled 57,779 Chinese adults aged 20 years or older with a multi-stage stratified cluster sampling procedure by Huang and colleagues (5). They reported the prevalence of chronic cough defined as lasting for >3 months each year was 3.6%, increasing with age from 2.4% among individuals aged 20–49 years to 6.0% among those aged 50 years or older. They also found that men had a higher prevalence than women in all age groups (4.6% vs. 2.6%), likely partly due to the significantly higher smoking rate of 47.2% in men compared to 2.7% in women (26). A cross-sectional study from China Taiwan based on the 2020 China Taiwan National Health and Wellness Survey (NHWS) found that the lifetime prevalence of chronic cough defined as self-reporting coughing daily for >8 weeks was 8.27%, and the 12-month prevalence defined as reporting it in the past 12 months was 5.55%, with a higher prevalence in those aged 65 years and older by Yu and colleagues (6). They also found that chronic cough was more prevalent among women and current smokers compared to those without the symptom.

In South Korea, Kang and colleagues (19) used cross-sectional data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) 2010–2012, and found that the prevalence of chronic cough defined as coughing for ≥8 weeks was 2.6% in subjects aged 18 years or older. They reported it was more prevalent in the elderly (≥65 years), which was independent of current smoking and comorbidities. There were 44.1% of participants with current cough who had a chronic cough. Additionally, the study showed that men had a significantly higher prevalence of chronic cough than women, at 3.3% compared to 2.0%, but it became statistically insignificant after adjustment for smoking status. Similarly, Yu and colleagues (6) based on the data from the 2020 South Korea NHWS reported a weighted prevalence of 4.34% of chronic cough defined as cough >8 weeks in the past 12 months for those aged 18 years or older. And they found that chronic cough was more prevalent in women than men (5.86% vs. 5.23%).

Using data from the 2019 Japan NHWS and a supplemental chronic cough survey, Tobe and colleagues (11) reported a 12-month prevalence of 4.29% of chronic cough defined as cough ≥8 weeks in the past 12 months for those aged 20 years or older. They also observed that individuals with chronic cough tended to be older and more predominantly male sex.

Southeast Asia

In Vietnam, a study randomly selected 3,008 subjects living in an inner-city area of Hanoi and 4,000 in a rural area of Bavi aged 21–70 years. Based on self-reported longstanding cough during the last years, Lâm and colleagues (10) reported that the prevalence of chronic cough was 18.1% in Bavi versus 12.0% in Hanoi, without significant age or gender difference in both areas.

Western Asia

Hamzaçebi and colleagues (20) reported a weighted prevalence of 10.6% of chronic cough defined as cough on most days >3 months each year for those aged 15 years or older based on the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) conducted in Turkey between October and December 2002. They also found that the prevalence of chronic cough was higher among the men than women (13.0% vs. 8.9%) increased with age, and the prevalence of chronic cough was higher among those who smoked more than 20 cigarettes per day than the other groups.

South Asia

In South Asia, the studies identified in this literature search were relatively outdated, and the variable definitions of chronic cough resulted in different prevalences. Bishwajit and colleagues (21) based on the data from the World Health Survey (2002–2003) found that the prevalence of chronic cough defined as coughing for 3 weeks or longer in the last 12 months was 14.4%, 11%, 15.3%, 10%, and 5.9% in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, respectively. A higher prevalence was observed in men than women in all the countries but Nepal, and a higher prevalence among those who reported smoking daily or occasionally compared to nonsmokers. However, a cross-sectional survey in India selected randomly among the general population aged 31 years or older in Mysore taluk, Mahesh and colleagues (22) found 2.5% of participants were diagnosed with chronic cough defined as coughing firstly in the morning or at any time during the day or night for as much as 3 months each year.

Central Asia

No studies in Central Asia were identified in this literature search.

Risk factors

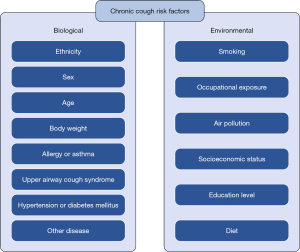

Risk factors for chronic cough have been explored in Asian population-based studies. It can be divided into two categories: biological factors and environmental factors (Figure 3).

Ethnicity

As discussed above, there was a significant variation in chronic cough prevalence among Asian regions. This inevitably led to the question of whether it was due to racial differences. Current research elucidated this from the perspective of cough physiological mechanisms. Capsaicin cough challenge testing was performed in 182 healthy volunteers of three distinct ethnic groups: Caucasian (white, non-Hispanic, of European origin), Indian (originating from the Indian subcontinent) and Chinese, and showed there were no significant differences in cough reflex sensitivity across ethnicities (27). Thus, the variable prevalence among races may be due to the impact of other factors, such as occupational exposure, air pollution, and socioeconomic status. Further research was needed to explore the relationship between racial factor and chronic cough.

Sex

Some early studies focused on the sex difference in cough sensitivity in Asia, for example, a study conducted in Chinese and Indian healthy people found lower cough thresholds in women by capsaicin cough challenge testing (27). Similarly, Song and colleagues (28) recruited 272 chronic cough patients from a tertiary cough clinic in Korea, found that women had a significantly higher capsaicin cough sensitivity than men. And the total challenge test counts of capsaicin-induced coughs were significantly higher for women aged more than 40 years, which indicated a higher prevalence of capsaicin cough sensitivity for elderly women.

However, the research results of the cough challenge testing were not consistent with recent epidemiological studies in Asia. Some studies showed that the prevalence of chronic cough had no significant difference in sex in Korea (29) and in Vietnam (10). Some studies suggested that the prevalence of chronic cough was higher in men than women, but sex was not an independent risk factor for chronic cough in multivariable adjusted analyses including age and cigarette smoking (5,19,22). In Turkey (20), a study based on the ECRHS found that the odds ratio (OR) for chronic cough for males was 1.51, with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 1.12–2.05, which was not corrected for multiple factor regression. Kang and colleagues (19) based on the KNHANES during 2010–2012, showed that chronic cough was significantly associations with male sex in univariate analysis, but after adjusting for smoking status, it lost its statistical significance. It may suggest that the associations with the male sex often observed in general population studies were probably due to current smoking.

Age

Most studies conducted in Asia showed that the prevalence of chronic cough in the general adult population significantly grew with age. In Korea, multivariate analysis showed that advanced age was associated with chronic cough in a general population based on the KNHANES 2010–2012 (19) and in participants aged ≥40 years with acceptable STOP-Bang questionnaire results based on the KNHANES 2019 (29). In China, the CPH study (5) showed that the prevalence of chronic cough increased with age, and it was an independent risk factor in multivariate analysis (increased 10 years, OR 1.43, 95% CI: 1.26–1.61). Besides, a study was conducted in a representative population in Mysore district in India confirmed independent association of age from 31–40 years to more than 71 years or older (OR 8.02, 95% CI: 4.07–15.79) (22). However, another study with a small size of 5,782 participants conducted in Vietnam with showed that chronic cough has no significant difference from 46–70 years to 21–45 years, in which the chronic cough was defined as coughing longstanding during the last years (10).

Body weight

The evidence for the relationship between body mass index (BMI) and chronic cough remains limited and inconsistent in Asia. Kim and colleagues (29) based on the data from the 2019 KNHANES, and grouped BMI to five groups according to the Asian-Pacific BMI classification (30). They found that obesity I defined as BMI between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 had a protective role against the occurrence of chronic cough after multiple factor adjustment, while the other BMI groups had no significant association with chronic cough. However, based on the data from the KNHANES 2010–2012, Kang and colleagues (19) reported there was no significant relationship between BMI and the occurrence of chronic cough in a multivariate analysis. Similarly, the CPH study (5) showed that BMI had no association with the prevalence of chronic cough and was not an independent risk factor.

Allergy or asthma

Many studies have shown that current or family history of the diseases related to allergic factor is a risk factor for chronic cough. For example, Liang and colleagues (31) found a more than 3-fold greater risk for subjects with allergy compared to those without allergy for suffering from chronic cough (OR 3.72, 95% CI: 1.85–7.47). The KNHANES 2010–2012 also demonstrated that chronic cough was significantly associated with self-reported physician diagnosis of asthma (OR 4.70, 95% CI: 3.11–7.10) (19), which was similar to the 2019 KNHANES (29). In another study targeting on a community population aged more than 65 years old in Korea, Song and colleagues (32) found that asthma and allergic rhinitis were risk factors for cough in this population. Similarly, the CPH study (5) showed positive relationships between allergic rhinitis with the prevalence of chronic cough (OR 2.84, 95% CI: 1.98–4.09).

Family history about diseases related to allergic factors was also an important risk factor for chronic cough. A meta-analysis covered an area of 11 Chinese provinces, Liang and colleagues (31) observed that family history of allergy was a risk factor for chronic cough in China (OR 1.74, 95% CI: 1.59–1.90). And it was statistically significant that people with a family history of respiratory conditions such as asthma had a higher risk of chronic cough (OR 1.67, 95% CI: 1.47–191). Similarly, a study conducted in rural and urban Vietnam demonstrated that family history of obstructive lung disease like asthma strongly associated with chronic cough (OR 3.42, 95% CI: 2.79–3.95) (10).

UACS

Another identified common cause of chronic cough was UACS, it was suggested the cause of 7.3% of chronic cough according to a study conducted in a hospital of Guangzhou, China (33). A meta-analysis focusing on the potential risk factors of chronic cough in China showed nasal or sinusitis diseases a 3-fold greater risk of chronic cough compared to those without (OR 3.56, 95% CI: 2.02–6.29) (31). However, Kang and colleagues (19), based on the KNHANES 2010–2012, demonstrated that allergic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis were not the independent risk factors of chronic cough, which was similar in participants aged ≥40 years with acceptable STOP-Bang questionnaire results based on the 2019 KNHANES (29).

Hypertension or diabetes mellitus

The correlation between chronic cough and hypertension or diabetes mellitus remained inconsistent. Kim and colleagues found that hypertension was not correlated with chronic cough in participants aged ≥40 years with acceptable STOP-Bang questionnaire results based on the 2019 KNHANES (29), which also supported by the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA) study (32). Lai and colleagues (33) observed only 0.4% with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor-induced cough among a total of 1162 patients with a primary complaint of chronic cough. In addition, the KNHANES 2010–2012 (19) indicated that chronic cough was significantly associated with self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes mellitus (OR 1.54, 95% CI: 1.01–2.24). This finding was supported by the KLoSHA (32) survey which defined uncontrolled diabetes mellitus as HbA1c more than 8%, and found it was a risk factor for chronic cough in the elderly. However, there were some studies that showed the opposite opinion that diabetes mellitus was not significantly associated chronic cough (5,29).

Other diseases

In addition, some studies have focused on the risk of chronic cough caused by some other diseases. Based on the 2019 KNHANES, Kim and colleagues (29) reported that obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) assessed by STOP-Bang questionnaire was a significant risk factor for chronic cough. Lai and colleagues (33) found GERD was one of the most common causes of chronic cough, with 12.5% of 1,162 patients with a primary complaint of chronic cough in China. However, Song and colleagues found GERD had no significant difference between chronic cough groups and control groups (2.8% vs. 1.0%) among the elderly aged more than 65 years old in Korea (32). Several studies conducted in Korea also found the relationship between psychological factors or the basic condition of patients and the risk of chronic cough. The KNHANES 2010–2012 (19) demonstrated that chronic cough was not associated with depression, while the KLoSHA survey (32) found constipation was a risk factor for chronic cough in the elderly.

Smoking

Most studies in Asia reported that smoking significantly contributed to the risk factor of developing chronic cough. For example, the KNHANES 2010–2012 found the current-smokers defined as people who were either currently smoked or had quit within the past 6 months had a threefold higher risk of chronic cough than those who never smoked or smoked less than 100 cigarettes in total (OR 3.01, 95% CI: 2.01–4.52) (19). It was consistent with the reports from the 2019 KNHANES data (29) and the KLoSHA study (32) that chronic cough independently correlated with current smokers. In China, the CPH study (5) showed that smoking was consistently associated with the prevalence of chronic cough in multivariable adjusted analyses (OR 2.61, 95% CI: 2.10–3.25). A meta-analysis from 28 studies which covered an area of 11 Chinese provinces also showed the consistent results (31), and found that people who were exposed to passive smoking had also higher risk of suffering from chronic cough (OR 1.44, 95% CI: 1.32–1.57). Similar results were reported from the studies conducted in Southeast and South Asia, for example, a study conducted in rural and urban Vietnam showed that current smoking was a risk factor for chronic cough (OR 1.45, 95%CI 1.16–1.80), but not for ex-smokers (10). Another study conducted in India by Mahesh and colleagues showed that the prevalence of chronic cough was associated with the total smoking consumption, and had a dose-dependent response relationship, which moderate-heavy smokers defined as smoking more than 14 pack years had a threefold risk of chronic cough than never-smokers (OR 3.19, 95% CI: 1.83–5.62) (22).

Occupational exposure

Most studies in Asia showed that occupational exposure was an important risk factor for chronic cough. The CPH study (5) showed that occupational exposure defined as exposure to dust, allergens, noxious gases (e.g. mining, forging, chemical industry, cement, greenhouse planting) for more than 3 months, was consistently associated with the prevalence of chronic cough (OR 1.41, 95% CI: 1.10–1.80). A meta-analysis conducted by Liang and colleagues (31) also demonstrated that individuals exposed to occupational pollutants had a trend for developing chronic cough, than those who were not exposed (OR 2.40, 95% CI: 1.34–4.29). Another study in India confirmed the risk of new-onset chronic cough was elevated in farmers (OR 2.02, 95% CI: 1.24–3.26) and retired (OR 2.30, 95% CI: 1.22–4.34), compared to housewife in a multivariate analysis (22). However, the KNHANES 2010–2012 showed that chronic cough was significantly associated with blue-collar occupation defined as workers in agriculture, forestry, fisheries, and craft and related trades, plant and machine operators, assemblers, and simple laborers, but it was not an independent risk factor of chronic cough (19). In addition, exposure to pets was linked to a greater likelihood of developing chronic cough compared to no exposure (OR1.37, 95% CI: 1.18–1.58) according to a meta-analysis in China (31).

Air pollution

Several studies from Asia have shown a significant association between air pollution and chronic cough. For example, a meta-analysis covered an area of 11 Chinese provinces, and found that people who had exposure to pollutants compared to those who were not exposed to pollutants had higher risks of developing chronic cough (OR 1.60, 95% CI: 1.26–2.04) (31). Another study from Palestine also showed that chronic cough defined as coughing at night in the last 12 months was frequently reported in those who lived the quarry sites less than 500 meters than those lived more than 500 meters away (11% vs. 0%) (34). Similarly, Hu and colleagues (35) observed a higher prevalence of chronic cough among the individuals living near major roads less than 100 meters in Beijing than those living over 200 meters away (OR 2.54, 95% CI: 1.57–4.10). They also found a dose-dependent response relationship between trafficrelated air pollution exposure and the prevalence of chronic cough. However, the CPH study (5) observed that biomass use defined as using woody fuels or animal waste for cooking or heating during the past 6 months or longer and exposure to high concentrations of particulate matter less than 2.5 (PM2.5) (≥75 µg·m−3) were not associated with the prevalence of chronic cough.

Socioeconomic status and education level

Researches on the relationship between socioeconomic status and education level and the risk of chronic cough were still limited. Kang and colleagues (19) classified household income as “low” or “high” at the 50th percentile, and demonstrated that chronic cough was significantly associated with low household income among the general population in Korea, but it was not an independent risk factors of chronic cough after adjusted by factors including age, sex, and occupation. Similarly, Kim and colleagues (29) based on the 2019 KNHANES study showed that low household income had almost triple the risk of chronic cough compared with high household income in univariate analysis (OR 2.866, 95% CI: 1.686–4.817), but it was not an independent risk factors of chronic cough after adjusted by factors such as age, sex, and smoking status. They also observed an increased prevalence of chronic cough in those who was unemployed or inactive compared with who employed in multivariate analysis (OR 1.660, 95% CI: 1.047–2.633). In view of the education level, the 2019 KNHANES study (29) showed that low educational level defined as middle school or less had a positive association with chronic cough in univariate analysis (OR 1.468, 95% CI: 1.024–2.105), but it was not an independent risk factor of chronic cough after adjusted by factors such as age, sex, and smoking status. Similarly, the CPH study (5) demonstrated education level was not the independent risk factor after adjusted by other factors, such as age, sex, and occupational exposure.

Diet

There was little research on the protective factors of chronic cough. Butler and colleagues (36) based on a population-based cohort of 63,257 middle-aged Chinese men and women initiated in Singapore, and demonstrated that high intakes of non-starch polysaccharides, certain non-citrus fruits (e.g., apples, pears), and total soya isoflavones were independently linked to a reduced risk of chronic cough.

Disease burden

An accumulating body of research indicates that the disease burden of chronic cough in general populations of Asia is huge and includes healthcare resource utilization, lung function impairment, comorbidities and concomitant symptoms, socioeconomic burden, and impact on life quality.

Healthcare resource utilization

Most studies could reach a consensus that patients with chronic cough in Asia had a higher healthcare resource utilization (HRU) compared to those without the disease. The CPH study (5) reported that people with chronic cough had more emergency room (ER) visits (3.5% vs. 0.5%) or hospital admission (5.5% vs. 0.4%) in the past 12 months because of worsening respiratory symptoms, which were significantly higher than those without chronic cough. And subgroup analysis showed that the influence of chronic cough on hospital admission was much more pronounced in patients with COPD, or small airway dysfunction (SAD) compared to those without. Using a population-based cross-sectional study comprising the 2019 Japan NHWS and a chronic cough survey, Kubo and colleagues (4) also reported that patients with chronic cough had significantly more visits to the healthcare professional (HCP) (7.71 vs. 5.25) and the ER (0.21 vs. 0.04). However, they found that HRU including HCP visits and ER visits in chronic cough patients had no association with the severity of chronic cough defined by visual analogue scale (VAS) (37). Similarly, Yu and colleagues (6) based on the 2020 South Korea and China Taiwan NHWS and a chronic cough survey, showed that there were more visits to HCP for chronic cough patients in the past 6 months. And they found patients with severe chronic cough (VAS>4) reported significantly greater number of visits to the HCP (10.13 vs. 4.96), compared to mild chronic cough (VAS <4) patients in South Korea.

Lung function impairment

Current research implied that chronic cough may be associated with lung function impairment. The CPH study (5) showed that people with chronic cough had lower lung function, including forced expiratory volume in one second/ forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC), maximal mid-expiratory flow (MMEF) percentage of predicted value (%pred), forced expiratory flow (FEF) 50%pred, and FEF 75%pred. Based on the data from the 2019 KNHANES conducted in Korea, Kim and colleagues (29) reported that chronic cough independently correlated with impaired lung function defined by FEV1 %pred. However, another study from Korea conducted in a community population aged more than 65 years old showed that airway obstruction defined as FEV1/FVC less than 70% had no association with chronic cough (32).

Comorbidities and concomitant symptoms

Some studies revealed that comorbidities and concomitant symptoms were considerable with a negative impact on the chronic cough patients. Using the data from the baseline KLoSHA survey in Korea, Song and colleagues found chronic cough patients were usually accompanied by more constipation (45.9% vs. 15.6%), gastritis (21.6% vs. 10.4%), asthma (16.2% vs. 3.1%), and allergic rhinitis (13.5% vs. 4.4%) in the elderly aged more than 65 years old, compared to those without chronic cough (32). Similarly, the CPH study (5) reported more hypertension in patients with chronic cough compared to those without (13.1% vs. 6.4%), and showed that phlegm was the most common concomitant symptom (67.5%), only 404 (22.6%) subjects with chronic cough had neither phlegm nor dyspnea and wheeze. In addition, patients with chronic cough reported more psychological problems and symptoms in Asia. A population-based cross-sectional study comprising the 2019 Japan NHWS and a chronic cough survey (4) reported more anxiety (3.9% vs. 1.5%), depressive symptoms (8.3% vs. 14.1%), and sleep problems and symptoms (66.2% vs. 48.7%) for chronic cough patients in the past 12 months, compared with matched non-cough respondents. However, these psychological concomitant symptoms in chronic cough patients were not associated with the severity of chronic cough defined by VAS. Based on the 2020 NHWS and a chronic cough survey in South Korea and China Taiwan, Yu and colleagues (6) reported a higher proportion of experience anxiety, depression, and insomnia in chronic cough patients compared to the matched non-cough respondents. Meanwhile, they observed there were more depression (39.8% vs. 16.5%) in patients with severe chronic cough compared to those with mild chronic cough in South Korea, while there was no correlation between psychological concomitant symptoms and the severity of chronic cough in China Taiwan.

Socioeconomic burden

There was almost no research report on the specific expenses of diagnosing and treating chronic cough, reduced work productivity, or unemployment, indicating an insufficient attention paid to patients with chronic cough in Asia. Only one review reported the burden for patients to pay 300,000 to 500,000 Korean won, about 450 United States dollars (USD) each time visiting the hospital by Won and colleagues (38). They also reported that chronic cough patients who were engaged in teaching children or interacting with others showed a more pronounced decline in work productivity or higher unemployment rates, which can lose about 1,000,000 Korean won (about 900 USD) in monthly salary. Patients with chronic cough had significantly increased absenteeism, presenteeism, total work productivity impairment, and total activity impairment, compared with matched non-cough respondents both in Japan (4) and South Korea (6), while only absenteeism was not significantly increased in patients with chronic cough in China Taiwan (6). In addition, based on the 2019 NHWS and a chronic cough survey in Japan, Kubo and colleagues (4) reported absenteeism (6.87 vs. 2.11), total work productivity impairment (29.56 vs. 21.77), and total activity impairment (31.21 vs. 25.04) significantly increased with severity of chronic cough. And there was only absenteeism significantly higher in Korea, while both absenteeism and total activity impairment were significantly higher in China Taiwan based on the 2020 NHWS as well as a chronic cough survey (6).

Impact on life quality

Currently, some studies have reached a consensus that chronic cough has a significant negative impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) of patients. HRQoL could usually be divided into two parts for evaluation: physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS). In the CPH study (5), it was reported that PCS was impaired in people with chronic cough (48.7 vs. 52.6), but not MCS, measured by the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) questionnaire after adjustment for factors including age and sex, which was significantly greater in elderly people or those accompanied with COPD. Similar to the CPH study, another study conducted in an elderly population from a small community in Korea showed that chronic cough was associated with an adverse impact not only on PCS but also predominantly on MCS of the Short Form 36 (SF-36) questionnaire (32). Similarly, based on the World Health Survey (2002–2003), self-rated health measured by a single question positively was associated with chronic cough in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka (21).

In addition, patients with chronic cough had a poorer HRQoL relative to matched non-cough respondents in terms of PCS and MCS, and worsen with the severity of chronic cough classified by VAS, based on the 2022 South Korea and China Taiwan NHWS and chronic cough survey (6) and the 2019 Japan NHWS (4). Kubo and colleagues (4) found that there was a correlation between cough-related quality of life (QoL) measured by Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ) and Hull Airway Reflux Questionnaire (HARQ) and cough severity in Japan. Health state utilities was a preference-based single index, which was usually used as a measurement for health and higher scores indicate better HRQoL. Several studies found poorer health state utilities measured by EuroQol Five Dimensions Questionnaire (EQ-5D) index or Short Form 6-Dimension (SF-6D) in patients with chronic cough compared to those without, and worsen with the increased severity of chronic cough in Japan (4), South Korea and China Taiwan (6). It may be explained that cough bout parameters as inter-cough intervals no more than three seconds, significantly correlated with cough severity measured by VAS in patients with refractory chronic cough, especially when single coughs were removed (39). And people with refractory or unexplained chronic cough, indicating the difficulty of controlling prolonged cough bouts, which hindered daily activities and reduced emotional well-being, thus affecting overall quality of life (40).

Conclusions

Chronic cough is a common complaint in clinical practice, which has attracted more attention. The reported prevalence varies widely among the general adult population in different regions of Asia, partly due to the variable definition of chronic cough. In addition, there are still some countries or regions lacking epidemiological data.

Risk factors for chronic cough can be roughly divided into biological and environmental factors. Currently, it mostly reaches a consensus on the risk factors of chronic cough, including age, allergy or asthma, smoking, occupational exposure, and air pollution. Other factors which are often cited based on empirical evidence, such as ethnicity, sex, body weight, other diseases, socioeconomic status, education level, and diet need further investigation.

Chronic cough is associated with a huge disease burden, especially in elderly and those with coexistent respiratory disease, including healthcare resource utilization, lung function impairment, comorbidities and concomitant symptoms, socioeconomic burden, and impact on life quality. In conclusion, chronic cough is a common symptom in the general population with some identifiable risk factors and great disease burden, which still need more attention in Asia.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnote

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the Guest Editor (Kefang Lai) for the series “the Fourth International Cough Conference (ICC) 2023” published in Journal of Thoracic Disease. The article has undergone external peer review.

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the Narrative Review reporting checklist. Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-248/rc

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-248/prf

Funding: This study was supported by

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-24-248/coif). The series “the Fourth International Cough Conference (ICC) 2023” was commissioned by the editorial office without any funding or sponsorship. K.H. reports that this study was supported by the Financial Budgeting Project of Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine (grant number YSBZ2024001, YSBZ2025001 to K.H.), and the Capital’s Funds for Health Improvement and Research (grant number CFH2024-1-1061 to K.H.). The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Morice AH, Millqvist E, Bieksiene K, et al. ERS guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in adults and children. Eur Respir J 2020;55:1901136. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung KF, Pavord ID. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and causes of chronic cough. Lancet 2008;371:1364-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Morice AH, Millqvist E, Belvisi MG, et al. Expert opinion on the cough hypersensitivity syndrome in respiratory medicine. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1132-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kubo T, Tobe K, Okuyama K, et al. Disease burden and quality of life of patients with chronic cough in Japan: a population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open Respir Res 2021;8:e000764. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang K, Gu X, Yang T, et al. Prevalence and burden of chronic cough in China: a national cross-sectional study. ERJ Open Res 2022;8:00075-2022. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yu CJ, Song WJ, Kang SH. The disease burden and quality of life of chronic cough patients in South Korea and Taiwan. World Allergy Organ J 2022;15:100681. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Definition and classification of chronic bronchitis for clinical and epidemiological purposes. A report to the Medical Research Council by their Committee on the Aetiology of Chronic Bronchitis. Lancet 1965;1:775-9.

- Irwin RS, Baumann MH, Bolser DC, et al. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129:1S-23S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin RS, French CL, Chang AB, et al. Classification of Cough as a Symptom in Adults and Management Algorithms: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2018;153:196-209. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lâm HT, Rönmark E, Tu'ò'ng NV, et al. Increase in asthma and a high prevalence of bronchitis: results from a population study among adults in urban and rural Vietnam. Respir Med 2011;105:177-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Tobe K, Kubo T, Okuyama K, et al. Web-based survey to evaluate the prevalence of chronic and subacute cough and patient characteristics in Japan. BMJ Open Respir Res 2021;8:e000832. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai K, Chen R, Lin J, et al. A prospective, multicenter survey on causes of chronic cough in China. Chest 2013;143:613-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McGarvey L, Gibson PG. What Is Chronic Cough? Terminology. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2019;7:1711-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pratter MR. Unexplained (idiopathic) cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2006;129:220S-1S. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Irwin RS, Corrao WM, Pratter MR. Chronic persistent cough in the adult: the spectrum and frequency of causes and successful outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis 1981;123:413-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song WJ, Chang YS, Faruqi S, et al. The global epidemiology of chronic cough in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2015;45:1479-81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kum E, Patel M, Diab N, et al. Efficacy and Tolerability of Gefapixant for Treatment of Refractory or Unexplained Chronic Cough: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2023;330:1359-69. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto S, Horita N, Hara J, et al. Benefit-Risk Profile of P2X3 Receptor Antagonists for Treatment of Chronic Cough: Dose-Response Model-Based Network Meta-Analysis. Chest 2024;166:1124-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kang MG, Song WJ, Kim HJ, et al. Point prevalence and epidemiological characteristics of chronic cough in the general adult population: The Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2010-2012. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6486. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hamzaçebi H, Unsal M, Kayhan S, et al. Prevalence of asthma and respiratory symptoms by age, gender and smoking behaviour in Samsun, North Anatolia Turkey. Tuberk Toraks 2006;54:322-9.

- Bishwajit G, Tang S, Yaya S, et al. Burden of asthma, dyspnea, and chronic cough in South Asia. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017;12:1093-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mahesh PA, Jayaraj BS, Prabhakar AK, et al. Prevalence of chronic cough, chronic phlegm & associated factors in Mysore, Karnataka, India. Indian J Med Res 2011;134:91-100.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021) Results. 2022. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2021

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Smoking Tobacco Use Prevalence 1990-2019. 2021. Available online: https://doi.org/

10.6069/FVQE-GR75 - Liang H, Ye W, Wang Z, et al. Prevalence of chronic cough in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med 2022;22:62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang M, Luo X, Xu S, et al. Trends in smoking prevalence and implication for chronic diseases in China: serial national cross-sectional surveys from 2003 to 2013. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:35-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dicpinigaitis PV, Allusson VR, Baldanti A, et al. Ethnic and gender differences in cough reflex sensitivity. Respiration 2001;68:480-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song WJ, Kim JY, Jo EJ, et al. Capsaicin cough sensitivity is related to the older female predominant feature in chronic cough patients. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2014;6:401-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim TH, Heo IR, Kim HC. Impact of high-risk of obstructive sleep apnea on chronic cough: data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BMC Pulm Med 2022;22:419. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pan WH, Yeh WT. How to define obesity? Evidence-based multiple action points for public awareness, screening, and treatment: an extension of Asian-Pacific recommendations. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2008;17:370-4.

- Liang H, Zhi H, Ye W, et al. Risk factors of chronic cough in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Respir Med 2022;16:575-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song WJ, Morice AH, Kim MH, et al. Cough in the elderly population: relationships with multiple comorbidity. PLoS One 2013;8:e78081. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai K, Zhan W, Li H, et al. The Predicative Clinical Features Associated with Chronic Cough That Has a Single Underlying Cause. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9:426-432.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nemer M, Giacaman R, Husseini A. Lung Function and Respiratory Health of Populations Living Close to Quarry Sites in Palestine: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:6068. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hu ZW, Zhao YN, Cheng Y, et al. Living near a Major Road in Beijing: Association with Lower Lung Function, Airway Acidification, and Chronic Cough. Chin Med J (Engl) 2016;129:2184-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Butler LM, Koh WP, Lee HP, et al. Dietary fiber and reduced cough with phlegm: a cohort study in Singapore. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2004;170:279-87. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Decalmer SC, Webster D, Kelsall AA, et al. Chronic cough: how do cough reflex sensitivity and subjective assessments correlate with objective cough counts during ambulatory monitoring? Thorax 2007;62:329-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Won HK, Song WJ. Impact and disease burden of chronic cough. Asia Pac Allergy 2021;11:e22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Holt KJ, Dockry RJ, McGuinness K, et al. An exploration of clinically meaningful definitions of cough bouts. ERJ Open Res 2024;10:00316-2024. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bali V, Schelfhout J, Sher MR, et al. Patient-reported experiences with refractory or unexplained chronic cough: a qualitative analysis. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2024;18:17534666241236025. [Crossref] [PubMed]