Characteristics of cardiothoracic surgeons practicing at the top-ranked US institutions

Introduction

Several US cardiothoracic (CT) surgical centers are renowned for their busy clinical volumes and outstanding outcomes, together with conducting innovative research and imparting state-of-the-art education. We previously showed that the annual rankings released by US News & World Report (USNWR), which are generally regarded as a reasonable correlate of the quality of patient care provided at a certain institution, are also a valid synthetic measure of the overall academic productivity of a CT surgical center, while ranking on the basis of National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding for research or designation as a stand-alone department vs. as a dependent division is not (1). In particular we found that CT surgical centers with the highest rankings in several USNWR hospital categories (such as “Honor Roll”, “Adult Cardiology and Heart Surgery”, “Adult Pulmonology”, and “Adult Cancer”) have the CT surgical faculty with the highest academic impact, as measured by their median H index. We also found that having a chairperson with a high personal academic output (in particular: a chairperson with an individual H index ≥50) has a beneficial impact on the scholarly productivity of the whole team. However, many topics remain to be addressed in order to pinpoint the characteristics that are truly necessary for professional success in CT surgery (2).

Here we aim to investigate which individual factors, if any, distinguish the CT surgeons practicing at the best US institutions from their peers, in terms of demographics (such as gender and seniority), prior training (in particular: any medical or post-graduate surgical training received outside the US, the reputation of the institutions where they received their education, and any prior training at the same center where they are currently faculty members), individual academic performance (citations, publications, H index) and research funding.

Methods

Selection of the institutions and data collection

The methods we used for the current study have been described previously (1,3).

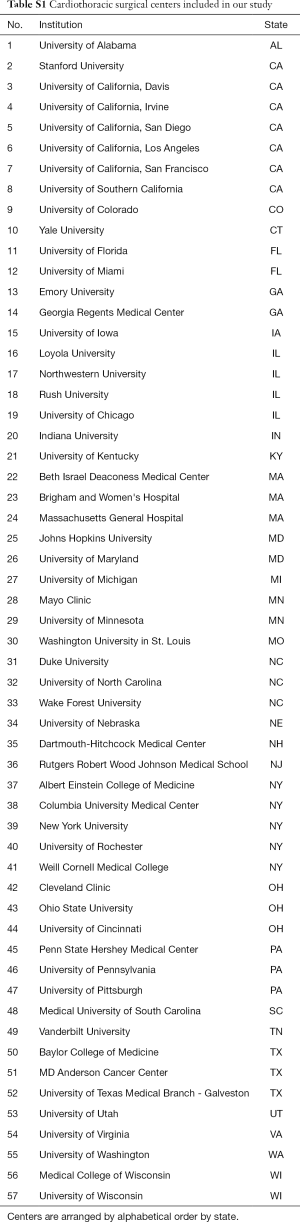

Briefly, we chose to examine the CT surgery faculty members of the 50 university-based departments of surgery with the highest NIH funding for research in the year 2014, as provided by the Blue Ridge Institute for Medical Research (http://www.brimr.org/NIH_Awards/2014/NIH_Awards_2014.htm). For one institution, we did not find any CT surgery faculty members. We then added eight institutions that are well-known academic CT centers, even if not among those with the highest NIH funding as defined above. We therefore considered 57 institutions overall (Table S1 in Supplementary Material).

Full table

An institution was classified among the “top CT centers” if, according to the USNWR 2015–2016, it was ranked among the top 10 institutions in the US in at least one of the following hospital categories: “Honor Roll”, “Adult Cardiology and Heart Surgery”, “Adult Pulmonology”, or “Adult Cancer”. Eighteen institutions (Table S2 in Supplementary Material) met such criteria and were therefore classified as “top CT centers”, while we will refer to the remaining 39 institutions as the “other CT centers”.

We accessed the website of each institution to identify their CT surgery faculty. We excluded faculty members who were not engaged in active clinical surgical practice or who were devoted exclusively to research. We used these same institutional websites and other online resources, including:

Full table

- SCOPUS database;

- NIH RePORTER (http://projectreporter.nih.gov/reporter.cfm);

- Grantome (http://grantome.com/);

- CTSnet (http://www.ctsnet.org/);

- US News&World Report (http://www.usnews.com/).

To get information about the CT surgical faculty, including:

- Training history: site and year of graduation from medical school, any attainment of a PhD degree, general surgery residency program, thoracic surgery fellowship program, any additional subspecialized CT surgical training (or “super-fellowship”), and the equivalent information in case of medical school or post-graduate surgical training received outside the US;

- Total number of publications and citations reported in the medical literature and the related H index;

- Any prior or current individual NIH research funding;

- Current academic rank, in any of the following four categories: Professor, Associate Professor, Assistant Professor, or Instructor;

- Institutional leadership role (being chairperson of a department or division).

Each surgeon was categorized as either a “cardiac” or a “thoracic” surgeon depending on the main focus of their current clinical activities. If a surgeon’s current clinical activity entailed both cardiac and general thoracic surgical procedures, there were assigned to the “cardiac” surgeon category. Similarly, surgeons focused on congenital CT surgery were classified as “cardiac” surgeons.

We divided faculty members into “junior” and “senior” depending on the time (≤20 or >20 years, respectively) since their graduation from medical school.

Statistical analysis

We used the open-access software R (https://www.r-project.org/). Contingency tables were analyzed using a chi-square test or a Fisher exact test, whenever appropriate. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare medians of two samples. Missing data points were excluded from computations of percentage values and from sample comparisons.

Results

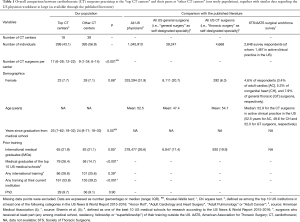

Among the 694 CT surgeons we considered, 489 (70%) were cardiac surgeons and 205 (30%) thoracic surgeons. Two-hundred and ninety-nine (43.1%) individuals were practicing at the “top CT centers” (18 institutions), while 395 (56.9%) at the “other CT centers” (39 institutions). There were 643 (92.7%) men and 51 (7.3%) women. Median time since graduation from medical school was 24 years (range: 7–71 years), with 254 (36.8%) junior (≤20 years) and 437 (73.2%) senior (>20 years since medical school graduation) CT surgeons, respectively. There were 148 (21.4%) international medical graduates (IMGs) and 542 (78.6%) US medical graduates (USMGs). Sixty-five (9.4%) CT surgeons had a PhD degree. There were 240 (37.1%) Professors, 151 (23.3%) Associate Professors, 217 (33.5%) Assistant Professors and 39 (6.0%) Instructors, respectively. The median number of total publications was 48 [range: 0-1,025; interquartile range (IQR): 17–112], the median number of total citations was 884 (range: 0–34,398; IQR: 242–2,698) and the median H index was 14 (range: 0–93; IQR: 7–26), respectively. One-hundred and fifty-two (22.0%) CT surgeons received NIH funding for research at any time (past or present) across their career. The size of CT surgery faculty at the “top CT centers” was larger than at the “other CT centers”, with a median number [range] of 17 [6–28] vs. 9 [1–34] CT surgeons per center, respectively (P<0.001) (Table 1).

Full table

Seniority

There was no difference in seniority: the median time (range) since medical school graduation was 25 years (7–62 years) for the “top CT centers” and 24 years (8–71 years) for the “other CT centers” (P=0.55).

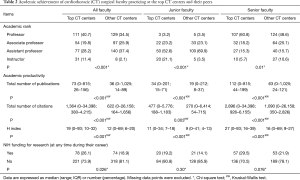

Academic productivity

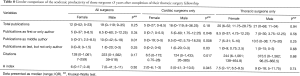

CT surgeons practicing at the top CT centers had higher career-long academic productivity in terms of number of publications, citations and H index (Table 2). Similarly, those practicing at the top CT centers were more likely to have ever received NIH funding for research during their career. Considering the whole study population, the median number of publications during residency, fellowship and in the first 5 years as an attending CT surgeon (i.e., after completion of a CT surgery fellowship) was 5 (range: 0–55), 2 (range: 0–36) and 10 (range: 0–143), respectively. The median number of publications as the first or only author during the same periods was 2 (range: 0–33), 1 (range: 0–17) and 2.5 (range: 0–37), respectively. The number of publications (both overall and as a first or only author) attained during CT fellowship and even more during the first 5 years after fellowship completion was positively associated with a higher current academic rank (professorship), institutional leadership role (being division/department chair) and recruitment at the top CT centers (Table 3). When individual data were plotted according to time from medical school graduation and academic rank, individuals with higher number of publications during their early career had achieved higher academic rank (Figure 1).

Full table

Full table

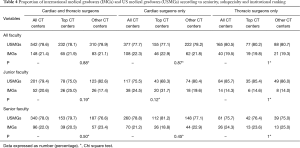

IMG/international training

There was no difference in the proportion of CT faculty who were IMGs at the “top CT centers” (21.9% of all, 25% of junior and 20.3% of senior surgeons, respectively) and their peers at the “other CT centers” (21.1%, 17.4% and 23.4%, respectively; P=0.88, P=0.19 and P=0.50, respectively) (Table 4).

Full table

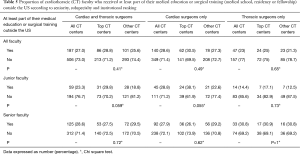

Similarly, when considering those faculty who received at least part of their training (any among medical school, residency, CT fellowship or super-fellowship) outside the US (27% of the whole population), no difference was found across institutional ranking (Table 5). However, we noticed a non-significant trend (P=0.055) towards a higher proportion of junior cardiac surgeons with any prior international training at the “top CT centers” (38.1%) than at the “other CT centers” (22.6%).

Full table

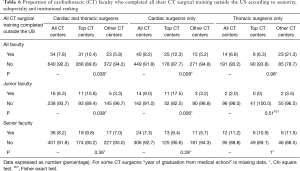

The proportion of faculty who completed their entire CT training (both medical school and CT residency and fellowship or their foreign equivalent) outside the US was higher at the “top CT centers” (10.4%) than at the “other CT centers” (5.8%; P=0.038). Subpopulation analysis revealed that such a difference was attributable to both junior faculty and cardiac surgeons (Table 6).

Full table

Prior training in the US

When examining prior medical education and surgical training in the US, surgeons of the “top CT centers” were more likely to be graduates of highly-ranked institutions than their peers (Table 7). For instance, the proportion of current CT surgery faculty who received at least part (82.9%) or all (25.8%) their training (medical school, residency and fellowship) at any of the “top CT centers” was higher than their peers (46.8% and 9.4%, respectively; P<0.001 for both comparisons). Moreover, surgeons of the “top CT centers” were more likely to have received at least part of their prior training at the same institution where they are currently faculty members than those at the “other CT centers” (53.8% vs. 39.2%; P<0.001).

Full table

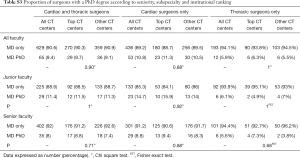

PhD degree

No significant difference in the attainment of a PhD was found between the “top CT centers” (where 9.7% of all faculty, 11.5% of junior faculty, and 8.8% of senior had a PhD degree) and the “other CT centers” (9.1%, 11.3%, and 7.4%, respectively; P=0.90, P=1 and P=0.71, respectively).

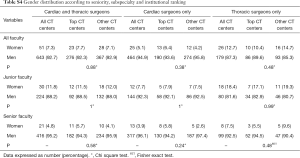

Gender

Fifty-one (7.3%) surgeons were female, with a lower prevalence among cardiac than among thoracic surgeons (5.1% vs. 12.7%; P<0 .001). Considering training history, no gender difference was found in the prevalence of CT surgeons who were IMGs (17.6% vs. 21.8%; P=0.61) or with a PhD (7.8% of women vs. 9.5% of men; P=1) (Table S3 in Supplementary Material). There was no difference in the proportion of female CT faculty across institutional ranking (Table S4 in Supplementary Material).

Full table

Full table

Women were less senior and less represented among higher academic ranks (Figure 2). Two (3.9%) women were chairpersons of their department/division vs. 122 (19.2%) men (P=0.01). Five (9.8%) women ever received NIH funding vs. 147 (23.0%) men (P=0.03). Gender differences in academic productivity (number of publications and role as author, citations, H index) of the youngest generation of CT faculty (those ≤5 years after thoracic surgery fellowship completion) are represented in Table 8.

Full table

Discussion

We aimed to investigate potential differences between CT surgeons practicing at the top-ranked US institutions and their peers. Several points deserve to be discussed.

Seniority

Using the 2015 report by the American Medical Association (AMA) (4), we were able to compare our study population with the overall US physician taskforce (1,045,910 individuals), all US general surgeons (i.e., those physicians who self-designated “general surgery” as specialty in the AMA registry: 39,247 individuals) and all US cardiothoracic surgeons (i.e., “thoracic surgery” as self-designated specialty in the AMA registry: 4,668 individuals) (Table 1). We did not have data regarding year of birth or age for our study population, but, considering that median time since medical school graduation was 24 years, it is reasonable to suppose that the median age of our population was about 50 years, which is comparable to the mean age of all US physicians (52.5 years), all US general surgeons (47.4 years) or all US CT surgeons (54.7 years).

A similar nation-wide comparison can be attempted by using the results of a survey performed by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS) in 2010 (5): the mean age of the surveyed CT surgeons in active clinical practice (1,467 individuals) was 52.9 years (52.5 years for the adult cardiac, 49.6 years for the congenital heart and 52.0 for the general thoracic surgeons, respectively), again comparable with our study population.

Our division of faculty members into “junior” (≤20 years) and “senior” (>20 years since their graduation from medical school, respectively) was arbitrary, but we think it represents a reasonable cut-off to distinguish fully-trained surgeons who are still climbing their learning curve from more mature individuals.

Academic productivity

We previously found that CT surgeons practicing at those centers with the highest USNWR rankings in the hospital categories “Honor Roll”, “Adult Cardiology and Heart Surgery”, “Adult Pulmonology”, and “Adult Cancer” (same criteria used here to define the “top CT centers”) have a higher academic productivity as measured by their H index (1). It comes to no surprise, therefore, that here we show in further detail that they have a higher number of total publications and citations (Table 2).

Those CT surgeons who published the most (in terms of total publications and also of publications as first or only author) during their early career years (namely during their residency, fellowship and in the first 5 years after fellowship completion) were more likely to attain advanced professorship positions, to become division/department chairperson and to be recruited at one of the top CT centers.

IMG/international training

IMGs face unique challenges when entering US surgical training and practice, yet they represent a large component of US physicians and of surgeons in particular (6,7). The proportion of IMGs among US CT surgeons (19.9% at the national level; 21.4% in our study population) is lower than the overall national prevalence (26.6%) (4). However, our data show that there is no difference in the proportion of IMGs between CT surgeons practicing at the top-ranked US surgical centers and those at other institutions. Of great interest, we found that the top-ranked CT surgical centers are those with the highest prevalence of faculty members who received part of or their entire CT surgical training abroad. This is likely the result of a virtuous cycle that is in place at those premiere CT institutions: thanks to their outstanding reputation and the professional opportunities they offer, those centers are able to attract the brightest and most innovative foreign CT surgeons; vice versa, those individuals, by training and/or practicing there, contribute to and reinforce the overall clinical and academic value of those institutions. It is therefore a characterizing feature of the best CT surgical centers in the US to have strong bonds with international institutions and individuals.

Prior training in the US

We found a strong correlation between practicing at one of the best CT centers and prior training at a highly-ranked institution as well, including, in the case of CT surgical faculty that are US medical graduates, graduating from one of the best US medical schools.

PhD degree

It is difficult to tell which training pathway is the most recommendable for a trainee who wishes to become a successful academic CT surgeon (2,8,9). Two recommendations that are often given are to dedicate extra time to research only (off clinical duties) during the training years (“go to the lab”), prolonging, by doing so, the duration of one’s training beyond the minimum time required for board certification, and to get a PhD degree. However, we previously showed that neither of these two pursuits is guarantee of subsequent lifelong professional achievement, in particular in terms of academic rank (i.e., attaining professorship) or institutional leadership role (becoming chairperson of a surgical division or department) advancement (3). Again, we did not find any significant difference in the prevalence of CT surgeons with a PhD (only 9.4% overall), being it between top CT centers and the other institutions or between senior or junior faculty.

However, it is undeniable that early engagement in a fruitful scholarly activity has a beneficial effect on overall success of an academic surgeon. Our current data show how early career academic productivity (number of ongoing publications) is associated with subsequent professional success, as discussed above (point “Academic productivity” of this Discussion). Actual scholarly output is therefore more predictive of long-term academic success than just “going to the lab” or getting a PhD.

Gender

The prevalence of women among US surgeons is lower than among non-surgical specialties, and this is especially true for certain surgical specialties, such as CT surgery (10). The proportion of women (7.3% overall) in our population was lower than among all US physicians (women: 31.9% overall) or all US general surgeons (women: 20.7%), but comparable with all US CT surgeons (women: 6.3%), according to the AMA4 (Table 1). In the STS/AATS national survey, women were 4.6% of the survey respondents (3.4% of the adult cardiac, 5.2% of congenital heart, and 7.9% of general thoracic surgeons, respectively) (5).

However, women represent an ever-expanding proportion among the youngest generations of CT surgeons. In our study population, we did not find any gender difference in terms of institutional ranking (“top CT centers” vs. “other CT centers”) and the proportion of IMGs or of surgeons with a PhD degree. Considering academic productivity in the early career years (Table 8), a factor that, as we showed (Table 3), is associated with lifelong career achievements, while among cardiac surgeons there was still a difference between genders (unfavorable for women), this was not the case for thoracic surgeons. The growing impact of women in CT surgery is well documented in the literature and is highlighted, for instance, by the history and successful initiatives of the Women in Thoracic Surgery association (5,11-15). Gender disparities are therefore expected to vanish in the coming years.

Conclusions

Our data show that:

- CT surgeons practicing at the “top CT centers” are more academically productive than their peers;

- Early career academic productivity (i.e., publications during residency, fellowship and in the first 5 years as an attending surgeon) is strongly associated with lifelong professional achievements in terms of academic rank (professorship) and institutional leadership role (division/department chair) advancement and recruitment as faculty member at the “top CT centers”;

- The proportion of academic CT surgeons with a PhD degree is low (9.4% in our population) and is not higher at the “top CT centers”;

- The proportion of IMGs among US CT surgeons (19.9% at the national level; 21.4% in our study population) is lower than among all US physicians (IMGs: 26.6%), but higher than among all US general surgeons (IMGs: 17.4%). The “top CT centers” are those with the strongest international bonds, in the sense that, while the proportion of IMG faculty members is the same across institutional ranking, those “top CT center” have the highest proportion of faculty who received all or at least part of their CT surgical training abroad;

- Women still represent a minority in CT surgery, especially among cardiac and senior surgeons. However, due to the growing prevalence of women among younger faculty, without significant differences in training and (for thoracic surgeons) early academic productivity, gender disparities at senior and leadership positions should decrease in the years to come.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Rosati CM, Vardas PN, Gaudino M, et al. Academic Productivity of US Cardiothoracic Surgical Centers. J Card Surg 2016;31:423-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Verrier ED. Getting started in academic cardiothoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;119:S1-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rosati CM, Valsangkar NP, Gaudino M, et al. Training Patterns and Lifetime Career Achievements of US Academic Cardiothoracic Surgeons. World J Surg 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- American Medical Association. Physician characteristics and distribution in the US. Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2015.

- Shemin RJ, Ikonomidis JS. Thoracic Surgery Workforce: report of STS/AATS Thoracic Surgery Practice and Access Task Force--Snapshot 2010. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:348-55, 355.e1-6.

- Itani KM, Hoballah J, Kaafarani H, et al. Could international medical graduates offer a solution to the surgical workforce crisis? Balancing national interest and global responsibility. Surgery 2011;149:597-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kaafarani HM. International medical graduates in surgery: facing challenges and breaking stereotypes. Am J Surg 2009;198:153-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rajagopal K, Whitson BA. Basic and translational research careers as early faculty cardiothoracic surgeons-perspectives from 2 young investigators. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2016;152:362-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stephens EH, Shah AA, Robich MP, et al. The Future of the Academic Cardiothoracic Surgeon: Results of the TSRA/TSDA In-Training Examination Survey. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:643-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Valsangkar N, Fecher AM, Rozycki GS, et al. Understanding the Barriers to Hiring and Promoting Women in Surgical Subspecialties. J Am Coll Surg 2016;223:387-398.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dresler CM, Padgett DL, MacKinnon SE, et al. Experiences of women in cardiothoracic surgery. A gender comparison. Arch Surg 1996;131:1128-34; discussion 1135. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Donington JS, Litle VR, Sesti J, et al. The WTS report on the current status of women in cardiothoracic surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:452-8; discussion 458-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burgess N. Women in Thoracic Surgery: our story. 30th Anniversary Celebration, January 2016 [cited 2016 Aug 25]. Available from: http://wtsnet.org/

- Antonoff MB, David EA, Donington JS, et al. Women in Thoracic Surgery: 30 Years of History. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:399-409. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stephens EH, Robich MP, Walters DM, et al. Gender and Cardiothoracic Surgery Training: Specialty Interests, Satisfaction, and Career Pathways. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;102:200-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]