一种适宜社区和基层应用的慢性阻塞性肺疾病初步诊断方法

摘要

目的:慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)的诊断和严重程度分级依赖肺功能检查,但是,肺功能在很多医院尤其是基层医院没有普及,致使相当部分COPD患者被漏诊或者误诊。本研究希望建立一种适合我国基层和社区应用的初步判别COPD病情的方法,以帮助基层医务人员对COPD患者进行初步的甄别,提高我国社区COPD

的防治水平。

方法:利用在广东农村和城市社区收集到的243例COPD患者及112例正常人资料作为训练样本,应用贝叶斯准则下的逐步判别分析方法,建立COPD的筛选判别函数,利用建立的判别函数对用同样的方法收集到的150例COPD患者及50例正常人进行判别。所有纳入者都予肺功能测试及支气管扩张实验检查。肺功能诊断按照GOLD指南标准。

结果:通过逐步分析的逐步筛选,筛选出生活环境(x1)、性别(x2)、年龄(x3)、气促级(x5)、吸烟指数(x7)、职业暴露史(x8)、体重指数(x11)、咳嗽(x12)、喘息(x14)9个判别因子最具有判别效果。敏感性、特异性、正相关率、负相关率、正确率、错判率分别为89.00%, 82.00%, 4.94, 0.13, 86.66% 和13.34%。预测COPD的正确率及 Kappa值分别为70% and 0.61 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.71)。

结论:应用贝叶斯准则下的逐步判别分析的方法筛选出用以甄别COPD的判别因子,建立的诊断COPD的数学模型,能够较好的用于社区与基层医院对COPD诊断和病情的初步判别

关键词:慢性阻塞性肺疾病、初步诊断、贝叶斯判别模型

前言

慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)是一种具有气流受限特征的可以预防和治疗的疾病,气流受限不完全可逆、呈进行性发展,与肺部对香烟烟雾等有害气体或有害颗粒的异常炎症反应有关。由于其患病人数多,死亡率高,社会经济负担重,已成为一个重要的公共卫生问题。目前居全球死亡原因的第4位,至2020年COPD将位居世界疾病经济负担的第5位(1-3)。而且在COPD的诊断中存在一定的漏诊误诊,大多数的COPD患者没有得到正确的诊断和治疗(4)。在近期的流行病学调查中(5)显示在诊断为“哮喘”、“肺气肿”、“支气管炎”、“COPD”的患者中仅有35.1%的患者进行过肺功能检查,在美国71.7%的中度气流受限的患者没有诊断为COPD (6)。

慢性阻塞性肺疾病(COPD)的诊断和严重程度分级依赖肺功能检查,但是,肺功能在很多医院尤其是基层医院没有普及(5)致使相当部分COPD患者被漏诊或者误诊。最近的流行病学调查显示(5),只有6.5%的被访者此前做过肺功能检查。因此寻找一种适合社区的简单经济的COPD的筛查和初步诊断的方法,对节省医疗资源、解决COPD在社区的筛查及初步诊断具有较大的实际意义。

材料与方法

病例资料

在广州市部分社区和韶关部分乡村进行COPD入户筛查,总共收集到343例COPD患者和162例正常人,年龄在40岁至86岁。具体筛查方法已在之前发表的论文中详述(7)。调查问卷参考BOLD研究的调查表,根据我国情况调整。肺功能的检查肺功能诊断标准按照GOLD指南,以扩张试验后FEV1 /FVC200ml为可逆试验阳,最少3次ATS能接受的肺功能曲线,重复性好,变异小。同时需排除肺结核、支气管扩张、充血性心力衰竭、肺癌等其他肺部疾病。将收集到的患者随机分成训练样本和考核样本2组,训练样本包括118例I-II级COPD患者,III-IV级COPD患者125例和112例正常人,此组样本用于建立贝叶斯准则下的数学模型。考核样本是从流调数据库中随机选择的I-II,III-IVCOPD患者及部分正常人,共150例,此组样本用于检验判别模型的特异性、敏感性及相关性。本实验设计由广州呼吸疾病研究所伦理委员会批准并且所有参与者都签署了知情同意书。

问卷调查

本实验所用问卷参考BOLD研究的调查表(8),与前期进行的流行病调查调查表相同(9)。内容包括:人口学资料,呼吸道症状(咳嗽、咳痰、气喘、气促),呼吸道疾病诊断及管理,COPD的潜在危险因素,共患疾病,呼吸困难的程度及健康状况评估(10),职业暴露指在有粉尘、气体、化学制剂等有害环境下工作超过1年。吸烟指数的计算是每天吸烟支数乘以吸烟年限。儿童时期有麻疹、百日咳及呼吸道感染史的为有儿童时期呼吸道感染史。家族成员例如父母及兄弟姐妹有COPD为有家族史。

肺功能检查

肺功能仪器标准满足美国胸科学会及欧洲呼吸协会肺功能标准(11,12)。采用应用便携式肺功能仪,每次启动肺功能仪时均应用容量定标器(3.0L)标定,误差<=3%,确定该肺功能仪工作正常。试前评估记录安全性问题。

支气管扩张试验采用 储雾罐方法吸入沙丁胺醇400μg ,15分钟后再次测试。扩张前后各最多进行8次测试,最少需获得3次ATS能接受的肺功能曲线,且最大最好的2次的FEV1和FVC变异小于0.2L,当FVC小于1L时,最大最好的2次的FEV1和FVC变异小于0.1L。

肺功能诊断按照GOLD指南,以扩张试验后FEV1 /FVC200ml为可逆试验阳,最少3次ATS能接受的肺功能曲线,重复性好,变异小。

质量控制

质控标准已在前期发表的论文里详述(4)。每个参与调查者都经过正规的培训并且考核合格。每个完成的调查问卷及肺功能报告都经过验证。所有数据经过编码后分别由两名研究者各自输入Excel表(Microsoft, Redmond, WA)。同时通过电脑程序纠错。

统计分析

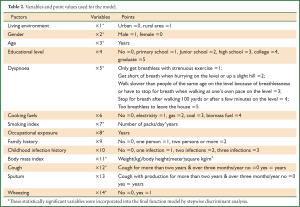

首先,根据相关文献报道及问卷的具体内容选取了生活环境(x1)、性别(x2)、年龄(x3)、教育程度(x4)、气促级(x5)、燃料级(x6)、吸烟指数(x7)、职业暴露(x8)、家族史(x9)、儿感史(x10)、体重指数(x11)、咳嗽(x12)、咳痰(x13)、喘息(x14)等14个指标作为甄别这3类调查对象所属类别的判别因子(9,13-38)。据训练样本应用贝叶斯准则下的逐步判别分析的方法筛选出用以甄别COPD的判别因子,应用筛选出的判别因子根据贝叶斯判别准则建立诊断COPD的数学模型。所有统计分析应用SAS9.1统计软件(SAS Institute, Cary, NC)完成。

结果

共收集到COPD患者243人,其中男性215人女性28人,年龄40-86岁。收集到的正常人共112例,男51例女61例,年龄40-79岁。所收集的资料中吸烟者占84%,大约有59%的病例来源于农村,详细资料见表 1

Full table

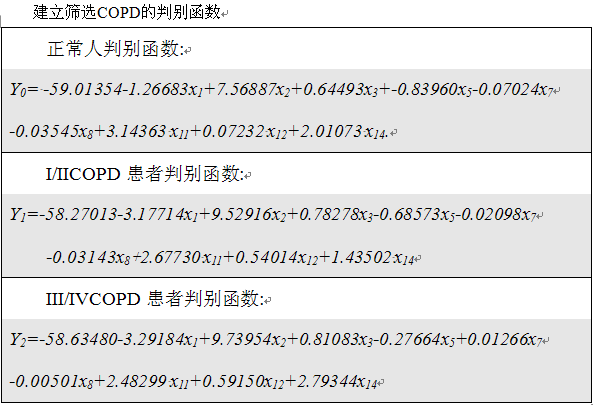

根据所选判别因子,利用贝叶斯逐步判别分析方法筛选出生活环境(x1)、性别(x2)、年龄(x3)、气促级(x5)、吸烟指数(x7)、职业暴露史(x8)、体重指数(x11)、咳嗽(x12)、喘息(x14)9个判别因子最具有判别效果。详细资料见(表 2) 。

Full table

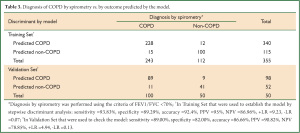

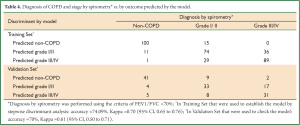

根据调查问卷我们可以知道每个病例资料的 x1, x2, x3, x5, x7, x8, x11, x12 及 x14 的具体数值,从而可计算出每个病例的 Y0, Y1 和 Y2 的具体数值,根据贝叶斯判别原理将该例归入Y值数值最大的一组。 利用所建立的模型对训练样本进行回顾性检验,模型的敏感性达到93.83%, 特异性为89.29%, 正相关率为9.23, 负相关率 0.07, 正确率为92.4% ,错判率为 7.6% 。利用模型对150例 进行判别,敏感性、特异性、正相关率、负相关率、正确率、错判率分别为89.00%, 82.00%, 4.94, 0.13, 86.66% 和13.34% (表 3)。判别模型的正确率为74.09% ,Kappa 值为 0.70 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.76) , 对COPD进行分级的回顾性检验中正确率为70%, Kappa 值为0.61 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.71) (表 4).

Full table

Full table

讨论

本研究建立了一种适合我国不能进行肺功能检查的基层和社区应用的初步判别COPD病情的方法,以帮助基层医务人员对COPD患者进行初步的甄别,提高我国社区COPD的防治水平,据我们所知虽然逐步判别分析的方法被用于其他疾病的诊断中(39),但应用逐步判别分析方法建立COPD的数学模型未见报道。

最近的研究显示不仅在中国在其他的发展中国家的社区医院里肺功能的使用率普遍较低。有研究提示可以应用调查问卷的方法对高危人群进行COPD的初步筛查(40-42)。我们根据简易的调查问卷应用建立的数学模型对COPD患者进行初步诊断筛查。本模型的灵敏度高(>89%)特异性强(>82%)可用于社区等基层医院尤其是广大农村没有肺功能的医疗单位对COPD的早期诊断。应用我们制定的简易的调查问卷及诊断软件基层医院的医生可以对COPD患者进行初步的诊断。与进行肺功能检查相比,我们制定的有9个问题的调查问卷更简单、易行、经济。我们的敏感性及特异性均高于根据调查问卷进行评分从而诊断COPD的诊断系统的敏感性和特异性,其特异性和敏感性分别为54 %至 82% ,58 %到88% (42)。而且我们的诊断系统可与对COPD患者进行初步的分级判断,其正确率达到70%。根据相关文献报道,我们选取了14个与COPD相关的危险因素作为判别因子(9-36)(表 2)。应用逐步判别分析的方法对14个判别因子进行筛选,最后筛选出9个危险因子作为调查问卷的筛查问题。与相关文献报道一致的是在我们筛选的判别因子中吸烟指数及体重指数(BMI)最具判别能力。众所周知,吸烟是COPD的发生发展过程中最直接相关的高危因素。在中国大概有2/3的COPD患者吸烟,其中有81.8%的男性患者,24%的女性患者吸烟。在吸烟者中有13.2%的人患有COPD,且抽烟越多患COPD的危险性越高。在韩国88%的男性COPD患者为吸烟者,在大于45岁的人群中每天抽烟大于20支的COPD的诊断率高达36%。BMI作为另外一个COPD的重要的相关因素,BMI与COPD呈负相关,BMI小于18.5 kg/m2的人群中COPD的患病率高达21%。在本研究中筛选出的判别因子作为危险因素在COPD的发生和发展中有着一定的作用,但是有些相关性较高的因子如燃料类型、咳痰的症状、儿童期的感染、受教育的程度、家庭环境被排除在外,这可能因为燃料类型与环境相关及受教育的程度与所选环境与年龄均相关,使得燃料级别在病例中没有明显差异。可以在今后的研究中对燃料级别进行仔细划分以后再进一步进行研究。 本研究中仅有355例样本资料,不能代表所有COPD患者的情况特点。入选病例资料中女性较少可能与COPD女性发病率明显低于男性有关。我们的COPD诊断标准采用GOLD指南的COPD标准,可能存在在老年人中过度诊断的问题。我们的诊断数学模型仅作为COPD初步筛查的工具,最后COPD的确诊还是要根据肺功能的结果做出诊断。最后我们的病例资料均来自于广东省,但根据COPD的危险因子筛选出的判别因子是普遍适用的,从而可能会影响模型的判别效果。

总之,本研究所应用贝叶斯准则下的逐步判别分析的方法筛选出用以甄别COPD的判别因子,建立的诊断COPD的数学模型,能够较好的用于社区与基层医院对COPD的筛选。对COPD患者早诊断、早治疗、节省医疗资源具有较大的实际意义。

Acknowledgements

Funding: This study was supported by the National Key Technology R&D Program of the 12th National Five-year Development Plan (2012BAI05B01). The funding providers, however, had no influence on the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of the data, writing of the report and the decision to submit the report for publication.

Contributors: JC collected the data, monitored data collection, planned the statistical analysis, analyzed the data, and drafted and revised the manuscript. YZ and JT collected the data and revised the manuscript. XW planned the statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. JZ monitored data collection and revised the manuscript. PR and NZ initiated and designed the project, monitored data collection, drafted and revised the manuscript. PR and JC are guarantors.

Competing interests: all authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest Form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author), and declared herein no support from any institution for the submitted work, no financial relationship with any institution that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years and no other relationship or activity that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: the study protocol was approved by Medical Ethic Committee at Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases and a written informed consent was given by all participants.

References

- Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:1256-76.

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990-2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 1997;349:1498-504.

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy--lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science 1996;274:740-3.

- Pauwels RA, Rabe KF. Burden and clinical features of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Lancet 2004;364:613-20.

- Zhong N, Wang C, Yao W, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China: a large, population-based survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:753-60.

- Mannino DM, Gagnon RC, Petty TL, et al. Obstructive lung disease and low lung function in adults in the United States: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1683-9.

- Liu S, Zhou Y, Wang X, et al. Biomass fuels are the probable risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in rural South China. Thorax 2007;62:889-97.

- Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Sullivan SD, et al. The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease Initiative (BOLD): rationale and design. COPD 2005;2:277-83.

- Cheng X, Li J, Zhang Z. Analysis of basic data of the study on prevention and treatment of COPD and chronic cor pulmonale. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 1998;21:749-52.

- Mannino DM, Buist AS. Global burden of COPD: risk factors, prevalence, and future trends. Lancet 2007;370:765-73.

- Standardization of Spirometry, 1994 Update. American Thoracic Society. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:1107-36.

- Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319-38.

- Kim DS, Kim YS, Jung KS, et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in Korea: a population-based spirometry survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:842-7.

- Tzanakis N, Anagnostopoulou U, Filaditaki V, et al. Prevalence of COPD in Greece. Chest 2004;125:892-900.

- Eisner MD, Balmes J, Yelin EH, et al. Directly measured secondhand smoke exposure and COPD health outcomes. BMC Pulm Med 2006;6:12.

- Eisner MD, Balmes J, Katz PP, et al. Lifetime environmental tobacco smoke exposure and the risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Environ Health 2005;4:7.

- Weinmann S, Vollmer WM, Breen V, et al. COPD and occupational exposures: a case-control study. J Occup Environ Med 2008;50:561-9.

- Bakke PS, Baste V, Hanoa R, et al. Prevalence of obstructive lung disease in a general population: relation to occupational title and exposure to some airborne agents. Thorax 1991;46:863-70.

- Humerfelt S, Eide GE, Gulsvik A. Association of years of occupational quartz exposure with spirometric airflow limitation in Norwegian men aged 30-46 years. Thorax 1998;53:649-55.

- Meijer E, Kromhout H, Heederik D. Respiratory effects of exposure to low levels of concrete dust containing crystalline silica. Am J Ind Med 2001;40:133-40.

- Hnizdo E, Murray J, Davison A. Correlation between autopsy findings for chronic obstructive airways disease and in-life disability in South African gold miners. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2000;73:235-44.

- Peabody JW, Riddell TJ, Smith KR, et al. Indoor air pollution in rural China: cooking fuels, stoves, and health status. Arch Environ Occup Health 2005;60:86-95.

- Viegi G, Simoni M, Scognamiglio A, et al. Indoor air pollution and airway disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8:1401-15.

- Huttner H, Beyer M, Bargon J. Charcoal smoke causes bronchial anthracosis and COPD. Med Klin (Munich) 2007;102:59-63.

- Ekici A, Ekici M, Kurtipek E, et al. Obstructive airway diseases in women exposed to biomass smoke. Environ Res 2005;99:93-8.

- Warren CP. The nature and causes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a historical perspective. The Christie Lecture 2007, Chicago, USA. Can Respir J 2009;16:13-20.

- Arbex MA, de Souza Conceição GM, Cendon SP, et al. Urban air pollution and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-related emergency department visits. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:777-83.

- Sauerzapf V, Jones AP, Cross J. Environmental factors and hospitalisation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a rural county of England. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:324-8.

- Zanobetti A, Bind MA, Schwartz J. Particulate air pollution and survival in a COPD cohort. Environ Health 2008;7:48.

- Zhou Y, Wang C, Yao W, et al. COPD in Chinese nonsmokers. Eur Respir J 2009;33:509-18.

- Fuhrman C, Delmas MC, pour le groupe épidémiologie et recherche clinique de la SPLF. Epidemiology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in France. Rev Mal Respir 2010;27:160-8.

- Kazerouni N, Alverson CJ, Redd SC, et al. Sex differences in COPD and lung cancer mortality trends--United States, 1968-1999. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13:17-23.

- Stojkovic J, Stevcevska G. Quality of life, forced expiratory volume in one second and body mass index in patients with COPD, during therapy for controlling the disease. Prilozi 2009;30:129-42.

- Montes de Oca M, Tálamo C, Perez-Padilla R, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and body mass index in five Latin America cities: the PLATINO study. Respir Med 2008;102:642-50.

- Pérez-Padilla R, Regalado J, Vedal S, et al. Exposure to biomass smoke and chronic airway disease in Mexican women. A case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996;154:701-6.

- Oxman AD, Muir DC, Shannon HS, et al. Occupational dust exposure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A systematic overview of the evidence. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;148:38-48.

- Künzli N, Kaiser R, Rapp R, et al. Air pollution in Switzerland--quantification of health effects using epidemiologic data. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 1997;127:1361-70.

- Stang P, Lydick E, Silberman C, et al. The prevalence of COPD: using smoking rates to estimate disease frequency in the general population. Chest 2000;117:354S-9S.

- Le Goff JM, Lavayssière L, Rouëssé J, et al. Nonlinear discriminant analysis and prognostic factor classification in node-negative primary breast cancer using probabilistic neural networks. Anticancer Res 2000;20:2213-8.

- Price DB, Tinkelman DG, Halbert RJ, et al. Symptom-based questionnaire for identifying COPD in smokers. Respiration 2006;73:285-95.

- Tinkelman DG, Price DB, Nordyke RJ, et al. Symptom-based questionnaire for differentiating COPD and asthma. Respiration 2006;73:296-305.

- Price DB, Tinkelman DG, Nordyke RJ, et al. Scoring system and clinical application of COPD diagnostic questionnaires. Chest 2006;129:1531-9.