Wedge resection for localized infectious lesions: high margin/lesion ratio guaranteed operational safety

Introduction

Localized infectious pulmonary lesions may form from abscess, aspergilloma and other granulomatous infections such as tuberculosis and coccidioidomycosis (1). Surgical management for these infectious lesions is commonly comprised of partial resection, lobectomy or pneumonectomy. The most difficult aspect of intraoperative planning for these focal diseases lies in determining whether the majority of the infiltrate could be anatomically excised (2).

Some surgeons chose partial resection for some small peripheral infectious lesion formations, would such non-anatomic resection increase the risk for post-operative complication?

In the present study, the authors retrospectively investigated clinical and pathological features for patients that received partial resection for infectious pulmonary lesions and also analyzed the risk factors for pulmonary complications of localized infectious lesions with limited resection.

Materials and methods

Patients

Wedge resection was in 1,325 cases of peripheral benign lung nodules in our centre between January 2008 and December 2012, included granuloma diseases 576 cases (tuberculosis granuloma in 534 cases, cryptococcal granuloma in 42 cases); infectious disease 171 cases [focal organizing pneumonia (OP) in 78 cases, lung abscess in 60 cases, aspergilloma in 23 cases, lung abscess combining aspergillus fumigates in 5 cases, and lung abscess combined with tuberculosis granuloma in 5 cases]; and other lung tumor 578 cases (hamartoma or fibroma in 310 cases, sclerosing hemangioma in 120 cases, pulmonary lymph node in 36 cases, pleuropulmonary sarcoidosis in 78 cases, bronchogenic cyst in 34 cases).

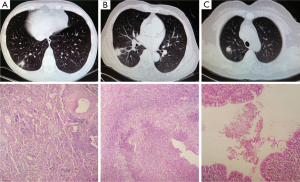

All of 171 cases of infectious disease were retrieved and corresponding H&E slides were reviewed by two pathologists (LK Hou and HK Xie), respectively. Focal OP was diagnosed by using criteria outlined in the American-European consensus statement on idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (3), cases with infiltrating inflammatory cells were included in our study. Neutrophils were present in the necrosis tissue of lung abscess which were characterized by suppurative inflammation with fibrosis in microscope. Final diagnosis of aspergilloma was achieved based on aspergillus founding in HE staining (Figure 1).

Finally, total 139 cases of localized infectious lesions were enrolled in our study, including focal OP in 46 cases, lung abscess in 60 cases, aspergilloma in 23 cases, lung abscess combining aspergillus fumigates in 5 cases, and lung abscess combined with tuberculosis granuloma in 5 cases. The group was 85 males and 54 females with a median age of 53 years (range: 21-74 years old). All patients underwent partial pulmonary resection (wedge resection) due to lesions in an HRCT slice that were highly suspect for lung cancer. Preliminary fibrobronchoscopy was routinely performed to preclude lesion involvement of the lobar and segment bronchus. Mediastinoscopy or endobronchial ultrasound-guided trans-bronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) was performed for patients with mediastinal lymph node enlargement.

Preoperative evaluations and operations

A thoracotomy or video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) procedure was applied to all patients; partial resection was carried out with a linear stapler or endoGIA. Stitches were routinely placed in the junction of staplers when more than two staplers using. The whole lesion was contained in resected specimens ensuring at least one centimeter of visibly lesion-free surrounding margins of the deflated lung. Frozen-section analysis was mandatory to determine the pathological nature of the lesion. Two chest tubes were positioned to the anterior and posterior for air leakage, blood, and plural effusion drainage. Chest tubes were removed when there was no air leakage and drainage was less than 100 mL over 24 h. Hospital mortality was defined as death that occurred within 30 days of the operation.

Post-operative management and pathological evaluation

The diameters, location, lesion-free stapled margins of all lesions were measured from the resected specimens.

Postoperative treatment

Patients with detection of tuberculosis received regular therapy with anti-tuberculosis drugs and follow-up from the outpatient service of the Tuberculosis Department. Patients with aspergillosis were given itraconazole orally for two weeks. Patients with lung abscesses were given intravenous antibiotics for three days.

Data collection

Information regarding underlying disease, clinical presentation, radiologic findings, diagnosis, operative procedure, complications, and follow-up was collected for further statistical analysis.

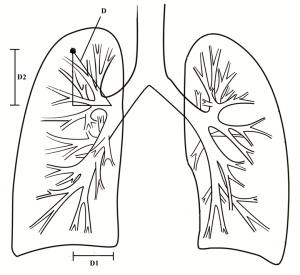

Radiological re-measurement

Preoperative high-resolution chest CT (HRCT) scan was available for all patients to assess the size, location, and characteristic of the lesion image. The data from HRCT included the diameter of the lesion and the distance (D) from the centre of the lesion to the lobe bronchus orifice (lobe where the lesion was located). We positioned the center of the lesion as one point at the lobe-orifice level with the help of an axis of coordinate using the CT scanning computer and measured the distance point to the lobe-orifice (lobe where the lesion was located) as D1. The distance between the cross section of the center of the lesion to the cross section of the lobe orifice was considered as D2, and we then deduced the following (Figure 2).

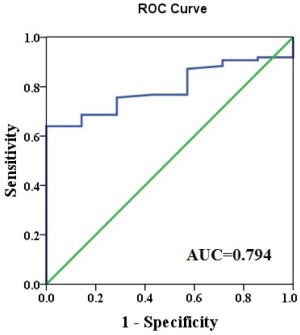

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). Variables were compared between the two groups using a Mann Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate analysis association with pulmonary complication was done using logistic regression analysis to identify potential independent risk factors. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Inc.). A significant difference was defined as a P value less than 0.05. The best cutoff value of the margin/lesion ratio to complication was determined by the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC).

Results

General information

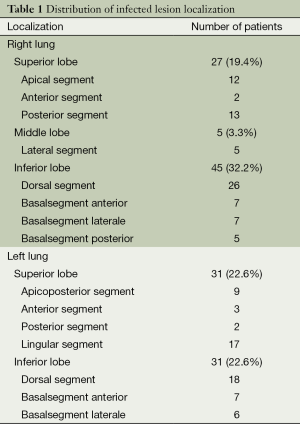

On initial presentation, 32 patients (23.0%) complained of hemoptysis, 30 patients (21.5%) had cough only, 18 patients (12.9%) had cough with bloody sputum, 18 patients (12.9%) had chest pain, 23 (16.5%) patients had high fever, one (0.7%) patient experienced shortness of breath, and 17 patients (12.2%) had a slight fever. According to medical histories, hypertension and type II diabetes were observed in four patients (2.8%), gastric ulcer was observed in two patients (1.4%), and emphysema in two patients (1.4%). Additionally, 36 patients (25.8%) had a history of smoking and 103 patients (74.2%) had never smoked. The distribution of infected lesion localization is presented in Table 1. All patients received fibrobronchoscopy. Four patients and 12 patients received mediastinoscopy and EBUS-TBNA examination respectively, and malignant cells were not obtained. Negative results were found in 22 cases receiving CT guided transthoracic needle biopsy.

Full table

There were 55 thoracotomies and 84 VATS procedures. Partial resection (wedge resection) in one lobar was completed in 137 patients and wedge excision in bilobar was performed in two patients. Median operative time and intraoperative bleeding were 97.5 min (IQR, 75-120 min) and 50 mL (IQR, 50-100 mL), respectively. The median chest tube drainage duration and intensive care unit (ICU) stay was 3 days (IQR, 2-4 days) and 2 days (IQR, 1-3 days), respectively. The median hospital stay was eight days (IQR, 5.25-12 days). In pathologic review, the median diameter of the lesions was 2 cm (1.2-3 cm) in a pathologic specimen, the median lesion-free stapled margin was 2.07 cm (IQR, 1.48-2.71 cm), and median rate of margin/tumor was 1.08 cm (IQR, 0.70-1.70 cm).

Radiographic finding

Lesions had the appearance of a nodule, mass, or cavity in 81, 35, and 23 cases, respectively. Lesions located at the peripheral lung tissue and the localization of lesions is detailed in Table 1. Eight cases had a thin wall cavity and 15 cases had a thick wall cavity; in the group of the nodules or mass (nodule: smaller than 3 cm in diameter) (4), well defined, irregular, and a linear outer margin was found in 18, 78, and 20 cases, respectively. Other simultaneous computed tomography findings included a satellite nodule in 10 cases, bronchiectasis in 16 cases, an air crescent sign in 14 cases, a gas fluid level in 10 cases, calcification in six cases, a vacuole sign in eight cases, and pleural indentation in five cases. The median distance from the centre of lesion to lobe bronchus opening was 6.78 cm (IQR, 5.82-7.92 cm), while the diameter of lesions was 1.89 cm (IQR, 1.29-2.63 cm). There was no significant difference in the diameter of lesions between CT scans and pathologic measurements.

Complications

A total of 12 cases (8.6%) developed post-operative complications in the present study. Post-operative pneumonia was confirmed in eight patients in this group, including three patients of lung abscess, three patients of lung abscess combining aspergillus fumigates infection and two patients of focal organization pneumonia excision. All patients had high fever 2-3 days post-operation, accompanying with elevating WBC count and mainly neutrophils; radiographic imagination showed a large patching dense shadow in the surgical lobe. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Candida were found by sputum culture respectively in three patients of lung abscess, these three patients were cured with sensitive intravenous antibiotics according to antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Three patients of lung abscess combining aspergillus fumigates infection were cured with empirical intravenous antibiotics and simultaneous oral itraconazole capsules. Two patients of focal organization pneumonia excision were cured with empirical intravenous antibiotics. Postoperative prolonged air leak (>7 days), which required no surgical intervention, occurred in two patients and was cured on the 11th and 12th postoperative days, respectively, by continuous negative pressure suction in a drainage bottle system and chest physiotherapy. Atrial fibrillation occurred in two patients on the 2nd and 3rd postoperative day and recovered with medical intervention. There was no perioperative or postoperative mortality in this group. Recurrences of infections were not found within 30 days of the operation.

Follow-up

Five (3.6%) patients were lost to follow-up, and 134 (96.4%) patients had regular follow-up. The end-point of follow-up was December 2012. The median period of follow-up was 21.5 months (range, 1-61 months; IQR, 6.75-35.25 months). One patient underwent wedge resection for lung abscess, and recurrence of high fever and purulent sputum five months postoperation and a lung abscess was confirmed by CT-guided percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy, and he underwent a left superior lobectomy after the diagnosis was confirmed; this patient fully recovered and was discharged one week after operation. One patient died two months after discharge because of pneumonia resulting in respiratory failure. One patient had accompanying intermittent incision pain and relied on painkillers. The remaining 131 patients were asymptomatic after surgery and had no evidence of disease elsewhere in the lung in the follow-up.

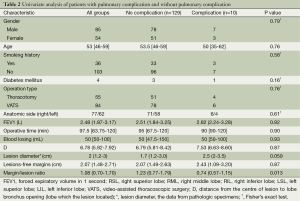

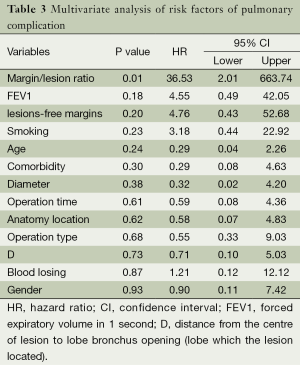

Univariate and multivariate analysis for pulmonary complications

The univariate analysis considered 13 variables between groups with no complications and complications with definite pneumonia (including two patients during follow-up within six months). Table 2 reports the results of the analysis. A risk factor associated with pulmonary complication was the margin/lesion ratio. All clinical variables were included in the multivariate analysis. The results are summarized in Table 3. Only one factor was independently associated with pulmonary complication: margin/lesion ratio (P=0.01). The relationship of the margin/lesion ratio to complication was analyzed by the receiver ROC, and the results showed that the best cut-off value for the margin/lesion ratio was 0.985 (Figure 3).

Full table

Full table

Discussion

Some localized lesions underwent surgical resection because the lesions mimicked lung cancer. Localized infectious lesions appearing in pulmonary parenchyma may be nodules, masses, or cavities, and some cases were accompanied by a vacuole sign or pleural indentation sign, thus, it was difficult in most cases to distinguish in the CT reading between benign or malignant. Even in PET-CT examination, abscess or fungal infection were common causes of increased 18F-FDG uptake, which mimicked lung cancer (5). In the present study, 83.5% (116/139) of lesions were nodule or mass, and 67.2% (78/116) of the nodules or masses had irregular margins. The lesions were highly suggestive of lung cancer through radiographic imaging, and surgical resection for those cases allowed for both diagnosis and cure.

Several studies have referred complications of limited resection for localized infection lesion exclusively. The most common complications for patients who underwent wedge resections were pulmonary related, regardless of open thoracotomy or VATS (6). In the reports by Mitchel et al. (7), 171 patients underwent 212 consecutive thoracoscopic lobectomies or sub-lobar for infectious lung disease and postoperative complications occurred in 19 cases (8.9%). In the study by Maldonado et al. (8), 24 patients had focal OP lesions and received sub-lobar resection by thoracotomy or VATS procedures, with postoperative pulmonary complications noted in two patients (8.3%). According to series reports for patients with infectious lesions, such as bronchiectasis, undergoing resection, the morbidity rates varied from 9% to 23% (9,10). Our findings in the present study were comparable with these results; the in-hospital complication rate was 8.6% (12/139) and pulmonary complications 5.7% (8/139). It was suggested that the approach of partial resection was feasible in patients with focal infectious.

The goal of surgery for treatment of localized infectious disease is to remove damaged lung parenchyma that can serve as a reservoir or nidus for recurrent infection (11). All reports emphasize the need for complete resection of focal infectious lung tissue associated with recurrent lung infection. Non-anatomic (wedge) resection for this kind of disease may result in insufficient resection range, and residual infectious tissue may contribute to pulmonary complications. In our study, univariate and multivariate analysis showed that the group with pulmonary complications yielded a significant difference in the margin/lesion ratio compared to the no complications group. Patients without complications had higher margin/lesion ratios (see Tables 2,3), and thus, it is implied that larger lesions should obtain longer lesion-free stapled margins to ensure sufficient excision.

It’s also reported that a margin/tumor ratio of less than one is associated with a higher rate of recurrence in patients of early-stage NSCLC that had undergone partial excision (12,13). The results of our research also demonstrated that the best cut-off value of the margin/lesion ratio for complications was 0.985; and a ratio of less than 0.985 had high pulmonary complications. The best cut-off value was approximately equal to one in our finding. We can draw a conclusion that relatively larger lesions should have a longer free margin, and that maintaining a margin/lesion ratio of more than one ensure better safely for limited resection of focal infectious lung disease.

Our study has several limitations. This was a retrospective study and only partial resection cases were included. The participants included in this study consisted of only 139 cases. Therefore, the small population may potentially influence the results.

Conclusions

For small peripheral pulmonary local infectious lesions, partial resection is an acceptable surgical manipulation choice, and maintaining a high margin/lesion ratio may better guarantee operational safety.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gould MK, Fletcher J, Iannettoni MD, et al. Evaluation of patients with pulmonary nodules: when is it lung cancer? ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest 2007;132:108S-130S.

- Pogrebniak HW, Gallin JI, Malech HL, et al. Surgical management of pulmonary infections in chronic granulomatous disease of childhood. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;55:844-9. [PubMed]

- American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277-304. [PubMed]

- Ost D, Fein AM, Feinsilver SH. Clinical practice. The solitary pulmonary nodule. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2535-42. [PubMed]

- Shim SS, Lee KS, Kim BT, et al. Focal parenchymal lung lesions showing a potential of false-positive and false-negative interpretations on integrated PET/CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;186:639-48. [PubMed]

- Howington JA, Gunnarsson CL, Maddaus MA, et al. In-hospital clinical and economic consequences of pulmonary wedge resections for cancer using video-assisted thoracoscopic techniques vs traditional open resections: a retrospective database analysis. Chest 2012;141:429-35. [PubMed]

- Mitchell JD, Yu JA, Bishop A, et al. Thoracoscopic lobectomy and segmentectomy for infectious lung disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;93:1033-9; discussion 1039-40. [PubMed]

- Maldonado F, Daniels CE, Hoffman EA, et al. Focal organizing pneumonia on surgical lung biopsy: causes, clinicoradiologic features, and outcomes. Chest 2007;132:1579-83. [PubMed]

- Prieto D, Bernardo J, Matos MJ, et al. Surgery for bronchiectasis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2001;20:19-23, discussion 23-4. [PubMed]

- Zhang P, Jiang G, Ding J, et al. Surgical treatment of bronchiectasis: a retrospective analysis of 790 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;90:246-50. [PubMed]

- Mitchell JD, Bishop A, Cafaro A, et al. Anatomic lung resection for nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1887-92. [PubMed]

- Sawabata N, Ohta M, Matsumura A, et al. Optimal distance of malignant negative margin in excision of nonsmall cell lung cancer: a multicenter prospective study. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;77:415-20. [PubMed]

- Schuchert MJ, Pettiford BL, Keeley S, et al. Anatomic segmentectomy in the treatment of stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg 2007;84:926-32; discussion 932-3. [PubMed]