|

Original Article

Clinicopathologic analysis of cardiac myxomas: Seven years’ experience with 61 patients

Ji-Gang Wang1, Yu-Jun Li1, Hui Liu1, Ning-Ning Li2, Jie Zhao1, Xiao-Ming Xing1

1Department of Pathology, the Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, 16 Jiangsu Road, Qingdao, Shandong Province, 266003, China; 2Department of Nephrology, the Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, 16 Jiangsu Road, Qingdao, Shandong Province, 266003, China

Corresponding to: Ji-Gang Wang. Department of Pathology, the Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Qingdao University, 16 Jiangsu Road, Qingdao, Shandong Province, 266003, China. Tel: +86-532-82911532; Fax: +86-532-82911533. Email: qdwangjigang@hotmail.com.

|

|

Abstract

Objective: Cardiac myxomas are the most common primary neoplasms of heart. The present study was performed on the 61 cases of patients with cardiac myxoma, in order to investigate the tumors’ clinical and pathological features, and to identify the relationship between the pathological characteristics and clinical behaviors.

Methods: A total of 61 cardiac myxoma cases were analyzed and reviewed retrospectively, including the clinical presentations, physical examinations, and echocardiography, electrocardiography, and pathology documents.

Results: The total patient cohort was made up of 37 women and 24 men. The average age at diagnosis was 48.8 years in males and 51.9 years in females. The most common complaint was dyspnea (37 cases, 60.7%) and the most common sign was systolic murmur (30 cases, 49.2%). Two surface structures and three tumor cell arrangement patterns were observed, and statistical analysis revealed the surface structure was related to the cell arrangement pattern. However, neither the cell arrangement pattern nor the tumor surface structure showed a significant correlation with the clinical presentation.

Conclusions: The present study showed the pathological profiles of cardiac myxomas were not related to the clinical presentations. The results of our study indicate morphologic classifications of cardiac myxomas may not be significant for clinical practice.

Key words

Cardiac neoplasms; myxoma; immunohistochemistry; pathology, surgical; neoplasm recurrence, local

J Thorac Dis 2012;4(3):272-283. DOI: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2012.05.07 |

|

Introduction

Primary tumors of the heart are extremely rare, with an estimated incidence ranged from 0.0017% to 0.33% at autopsy ( 1). Cardiac myxomas represent the most frequent benign cardiac tumors. In most surgical series, they account for almost 80% of cases ( 2). The cells giving rise to the tumor are considered to be multipotential mesenchymal cells that persist as embryonal residues during septation of the heart ( 3, 4). They also are thought to arise from cardiomyocyte progenitor cells, subendothelial vasoformative reserve cells or primitive cells which reside in the fossa ovalis and surrounding endocardium or endocardial sensory nerve ( 5- 8). Occasionally, mucous glandular epithelium may present, which may represent rests of entrapped embryonic foregut ( 9, 10). Two types of macroscopic appearance are observed: polypoid type and papillary type ( 11, 12). The histopathological diagnosis of a cardiac myxoma depends on the identification of the myxoma cell, which has occasionally been called the lepidic cell ( 13). The cells are arranged singly or in small clusters, or formed capillary like channels ( 2). Some morphological and immunohistochemical features may be related to the clinical presentations. Burke found that embolic myxomas were less often fibrotic than nonembolic myxomas and were more likely thrombosed and extensively myxoid with an irregular frond-like surface. Fibrotic and non-thrombosed tumors had a longer mean duration of clinical symptoms and were found in older persons. Recurrent, multiple, and familial myxomas were more often found in younger women and, more likely irregular surfaced and histologically myxoid ( 4). Endo’s group reported that tumors associated with constitutional signs were significantly more likely to be large, multiple, or recurrent than those unassociated with

constitutional signs ( 14). Papillary surface myxomas are thought

to be related to embolism, and large left atrial tumors are related

to atrial fibrillation. Myxoma cells usually express IL-6, and some

tumors have abnormal cellular DNA content ( 15). A C769T

PRKAR1a mutation has been observed in “familial myxomas” ( 16). Previous studies have reported a large series of myxomas,

however, little was focusing on the histopathologic classifications,

and the origin of the myxoma cells is still controversial ( 8).

Moreover, there is still no study related to cardiac myxoma in

Shandong Peninsula. Therefore, we presented a retrospective

review of our institution’s experience to investigate the clinical

and pathological features of cardiac myxomas, and to identify the

relationship between the pathological characteristics and clinical

presentations. |

|

Materials and methods

Materials

61 consecutive cases of cardiac myxomas, surgically resected

at the Cardiac Surgery Department of the Affiliated Hospital

of Medical College, Qingdao University, were identified by

searching the surgical pathology database during the seven-year

period between 2004 through 2010. During the seven years’

period, a total of 71 primary cardiac or pericardiac tumors had

been identified, including myxomas (61 cases, occupied about

85.9%), malignant fibrohistiocytomas (2 cases), non-Hodgkin’s

lymphomas (2 cases), low grade myxofibrosarcoma (1 case),

liposarcoma (1 case) ( 17), angiosarcoma (1 case), hemangioma

(1 case), papillary fibroelastoma (1 case), and rhabdomyoma (1

case). Approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional

Review Board. The medical records were reviewed with clinical

presentations, methods of diagnosis, management. Followup

was made by contacting with referring physicians or by

telephone. Pathologic study

All tumors underwent surgical resection after imaging diagnosis.

The tumor location and maximal diameter were evaluated in

all cases. All specimens were fixed in 10% buffered formalin

and embedded in paraffin, and then treated with Hematoxylin

and Eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemical staining.

The latest ten cases were treated with Alcian blue-Periodic acid

schiff (AB-PAS) staining to determine and identify carbohydrate

macromolecules of the myxoid stroma. When detected by ABPAS

staining, neutral mucopolysaccharides are stained “purplemagenta”

by schiff ’s reagent, acid mucopolysaccharides are

stained “blue” by alcian blue, and the complex of the both are

stained “purplish red”. A panel of antibodies, including CD34,

CD68, smooth muscle actin (SMA), epithelial membrane

antigen (EMA), Vimentin, and cytokeratin (CK), was used for

immunohistochemical staining (all antibodies were from Santa

Cruz, Beijing, China). The specificity of immunolabeling was

demonstrated by the absence of labeling of the antigen when the

primary antibody was omitted. All slides were reviewed by two

independent pathologists using an Olympus BX-51 microscope

(Tokyo, Japan). Only the brown particles that were easily visible

with a low power objective was categorized positive staining.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software for Microsoft Windows.

Mean values between two groups were compared by Student

t-tests. The associations between the morphological features and

clinical presentations were determined by Pearson’s chi-square

tests with correction for the continuity. The criterion level of

significance was P<0.05 for all comparisons. |

|

Results

Clinical findings

60 cases were sporadic myxomas and 1 case was familial

myxoma. The total patient cohort was made up of 37 women

and 24 men (female/male ratio was 1.5). Patients’ age ranged

from 12 to 76 years (mean age was 50.7±15.7 years). Most

patients were in the fifth, sixth and seventh decades of life (39 of

the total 61 cases, account for 60.7%). It was rare in individuals

younger than 30 years (5 cases, less than 10%). The average age

at diagnosis was 48.8 years in males and 51.9 years in females

(P=0.46, no significant difference between males and females).

The myxomas involved predominantly the left atrial cavities

(54 cases, 88.5%). Besides, there were six right atrial myxomas

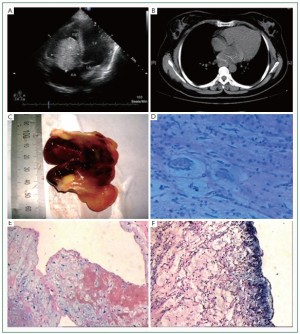

(9.8%) and one right ventricular myxoma (1.7%) ( Figure 1A).

The detailed descriptions of the six right atrial myxomas and one

right ventricular myxoma are offered in Table 1. Most myxomas

were attached to the septum by a stalk (57 cases, 93.4%). The

right ventricular myxoma was originated from the regulating

bundle branch.

| Table 1. Clinicopathologic features of 6 right atrial and 1 right ventricular myxomas. |

| Age (years)/sex |

Symptoms/ signs |

Location |

Tumor size (cm) |

Macro/histopathology |

Follow-up |

| 69/Male |

Dyspnea and palpitation |

Right atrium (atrial

septum) |

6×3×3 |

Papillary/significant

hemorrhage and

necrosis |

Recovered |

| 30/Male |

Found during

echocardiography after

a “biatial and right

ventricular myxoma

excision” operation seven

years ago |

Right atrium (atrial

septum), tricuspid valve |

4×4×2, 1 |

Solid/ cell cord

predominant |

Recovered |

| 49/Female |

Asymptomatic |

Right atrium (atrial

septum) |

3.5×2.4×2 |

Papillary/significant

hemorrhage and

necrosis |

Recovered |

| 50/Male |

Dyspnea and angina |

Right atrium (atrial

septum) |

3×2.2×2 |

Solid/cell cord

predominant |

Recovered |

| 35/Female |

Dyspnea and palpitation |

Right atrium (atrial

septum) |

6×5×3 |

Papillary/single cell

predominant |

Recovered |

| 19/Female |

Cough |

Right atrium (atrial

septum) |

7×7×5 |

Papillary/cell cord

predominant |

Recovered |

| 34/Male |

Syncope |

Right ventricle, originated

from the regulating

bundle branch |

7×5×3.5 |

Solid/single cell

predominant |

Recovered |

Clinical presentations are described in Table 2. Dyspnea was

the most frequent complaint at diagnosis (60.7%). The course

of disease at presentation ranged from two days to twenty years.

Four cases (6.6%) were asymptomatic. Of these four myxomas,

three were located in the left atrium and one located in the right

atrium. The four myxomas were incidentally found during other

preoperative examination or routine examination.

| Table 2. Clinical presentations of 61 patients. |

| Symptoms |

Course of disease |

Total (61) |

|

Left Atrial (54) |

|

Right Atrial (6) |

|

Right Ventricular (1) |

| Cases |

% |

Cases |

% |

Cases |

% |

Cases |

% |

| Cardiac |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Dyspnea |

5 days - 20 years |

37 |

60.7 |

34 |

63.0 |

3 |

50 |

- |

- |

| Palpitation |

2 days - 20 years |

28 |

45.9 |

26 |

48.1 |

2 |

33.3 |

- |

- |

| Cough |

8 days - 6months |

4 |

6.6 |

3 |

5.6 |

1 |

16.7 |

- |

- |

| Angina |

1 week - 30 years |

3 |

4.9 |

2 |

3.7 |

1 |

16.7 |

- |

- |

| Edema of lower limbs |

1 year |

1 |

1.6 |

1 |

1.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Central nervous |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vertigo |

6 months - 6 years |

4 |

6.6 |

4 |

7.4 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Cerebral infarction |

10 days - 7 months |

2 |

3.3 |

2 |

3.7 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Syncope |

3 days |

1 |

1.6 |

- |

|

- |

- |

1 |

100 |

| Systemic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fatigue |

6 months - 2 years |

4 |

6.6 |

4 |

7.3 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Fever |

2 months - 4 months |

3 |

4.9 |

3 |

5.6 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Asymptomatic |

- |

4 |

6.6 |

2 |

3.7 |

2 |

33.3 |

- |

- |

Abnormal physical examination findings were recorded in 54

cases (88.5%). The most common sign was the systolic murmur

(30 cases, 49.2%), and then followed by the diastolic murmur

(19 cases, 31.1%). The murmur was often altered along with the body position. Tumor plop could be heard in 10 patients

(16.4%). Other abnormal cardiac signs included the loud first

sound (15 cases, 24.6%), the loud second sound (10 cases,

16.4%), and the opening snap (6 cases, 7.4%). Two-dimensional

echocardiography was performed in all patients, which could

well determine the tumor location, size, shape, attachment and

mobility. There was no misdiagnosis with echocardiography.

Radiological examinations (computed tomography or magnetic

resonance imaging) of the chest were only available in several

cases ( Figure 1B). Electrocardiography documents were

available in 55 cases, and abnormal findings were reported in 30

cases (54.5%), including signs of atrial hypertrophy (20 cases,

36.4%), atrial fibrillation (7 cases, 12.7%), arrhythmia (2 cases,

3.6%), and tachycardia (1 cases, 1.8%).

All patients underwent complete myxoma excisions with

cardiopulmonary bypass after echocardiographic diagnosis.

The patient with the recurrent right atrial myxoma also received

tricuspid valve repairing surgery. There were 50 cases available

for follow-up (ranged from 6 months to 7 years). Two cases died

of other diseases. There was one case bear a recurrence during

the follow-up period (2 years after the first surgery). The patient

underwent second surgery and recovered uneventfully after that.

Other 47 cases recovered uneventfully. Among them two cases

had accepted “myxoma resection” surgery at other institutions

7 years and 20 years before. Unfortunately, it is impossible for us

to get the detailed information at that time.

Gross pathology

The mean maximal diameter was 5.8±1.8 cm (ranged from 2 to

11 cm). There was no significant difference between the left and

right (left: 5.9±1.8 cm, right: 4.8±1.8 cm, P=0.13). The maximal

diameter of four asymptomatic cases was 6, 4, 3, and 3 cm,

respectively. On gross examination, the tumors had broad base,

and most have pedicles (57 cases). The tumor mass was soft,

gelatinous, and very friable. They were smooth and glistening

(solid type, 18 of 30 available cases with gross description) or

had multiple papillary, villous, finger-like projections (papillary

type, 12 of 30 cases). Two cases presented with cerebral

infarction symptoms were papillary type. The cut surface

was variable; most cases were soft, gelatinous, pale grey with

hemorrhage areas, others were a little firmer, or with calcification

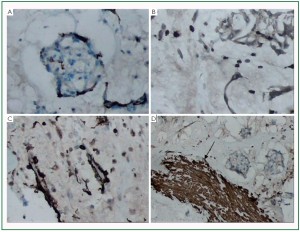

( Figure 1B, 1C). Histopathology

On microscopy, myxoma was made up of a myxoid stroma

with variable myxoma cells. The stromal matrix was loose,

homogenized and red-stained, which contained variable

amounts of proteoglycans, collagen and elastin. Using ABPAS

staining, we found that the stromal matrix appeared to

be purplish red (positive for AB and PAS), while the mucous

halo showed blue color (positive for AB) ( Figure 1D). Variable

amounts of thin walled blood sinus or thick walled blood

vessels were often present. Hemorrhagic foci, fibrinoid necrosis,

hemasiderin-laden macrophages, and inflammatory cells were

also frequent. The tumor cells may be spindle, polygonal, or

stellate, and have round to oval nuclei with inconspicuous

nucleoli, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and indistinct borders. Mitoses

are rare. The cells could be arranged in single, in nests or cords,

or in vasoformative ring structures. Small or large mucous halos

were frequently observed to surround the myxoid cells, the cords

or vasoformative ring structures. In fact, most myxomas were

combined with the above two or three structures. 2 cases had

extensive hemorrhage and necrosis, which made it difficult to

classify. According to the arrangement pattern of tumor cells, we

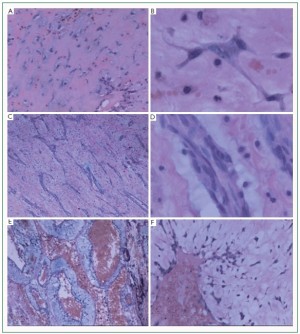

categorized the other 59 myxomas into three subtypes: Single

cell predominant subtype, cell cord predominant subtype,

and vasoformative ring predominant subtype ( Figure 2). The

majority of myxomas were belonging to single cell predominant

subtype (28 cases, 47.5%). The cell cord predominant type often

showed rudimentary “chicken-wire” vessels like appearance, with

few and scattered single myxoid cells in the stroma. There were

21 cases belonging to this subtype (35.6%). The vasoformative

ring predominant subtype showed a hemangioma-like

appearance, containing distended blood sinus and positive alcian

blue stained myxiod halo. 10 cases were categorized into this

subtype (16.9%). Calcification was observed in 3 cases. Besides,

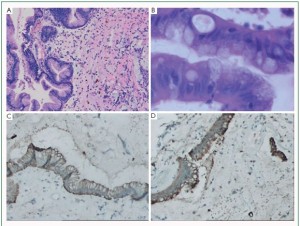

well-defined mucous glands, containing goblet cells interspersed

between cells, formed by columnar epithelium were found in 2

cases ( Figure 3A, 3B). According to the microscopic appearance of tumor surface, all

myxomas also could be divided into two subtypes: solid subtype

(29 cases) and papillary subtype (30 cases) ( Figure 1E, 1F).

Sometimes the tumor with clefted area made the differentiation

between the two subtypes difficult. In the present study, we

categorized such tumors into the former subtype. Only those

observed with obvious papillary architecture under low power

were categorized into papillary subtype. We found the two

subtypes have different cell arrangement patterns. The papillary

subtype appeared more likely to form a single cell predominant

pattern, whereas the solid subtype was more likely to form

rudimentary vessels ( Table 3). Moreover, statistical analysis

revealed there was no significant difference between these

morphological features and clinical symptoms ( Table 4).

| Table 3. Morphologic features of 59 myxomas (cases). |

| |

Solid |

Papillary |

| Single cell predominant |

7 |

21 |

| Cell cord predominant |

13 |

8 |

| Vasoformative ring predominant |

9 |

1 |

| The cell has expected count less than 5. Chi-square test showed the solid subtype and papillary subtype have different cell

arrangement architectures (x2=13.163, P=0.001). |

| Table 4. Correlation of clinical presentations and morphologic features (cases). |

| Symptoms |

Total |

Surface |

|

Cell arrangement |

P value |

| Solid (29) |

Papillary (30) |

Single (28) |

Cord (21) |

Ring (10) |

| Cardiac |

|

|

|

0.904 |

|

|

|

0.520 |

| Dyspnea |

37* |

18 (62.1%) |

18 (60.0%) |

19 (67.9%) |

11 (52.4%) |

6 (60.0%) |

| Palpitation |

28* |

13 (44.8%) |

14 (46.7%) |

14 (50.0%) |

9 (42.9%) |

4 (40.0%) |

| Cough |

4 |

3 (10.3%) |

1 (3.3%) |

3 (10.7%) |

1 (4.8%) |

0 |

| Angina |

3 |

2 (6.9%) |

1 (3.3%) |

0 |

3 (14.3%) |

0 |

| Edema of lower limbs |

1 |

1 (3.4%) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 (30.0%) |

| Central nervous |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vertigo |

4 |

2 (6.9%) |

2 (6.7%) |

1 (3.6%) |

1 (4.8%) |

2 (20.0%) |

| Cerebral infarction |

2 |

0 |

2 (6.7%) |

2 (7.1%) |

0 |

0 |

| Syncope |

1 |

1 (3.4%) |

0 |

1 (3.6%) |

0 |

0 |

| Systemic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fatigue |

4 |

3 (10.3%) |

1 (3.3%) |

1 (3.6%) |

1 (4.8%) |

2 (20.0%) |

| Fever |

3 |

1 (3.4%) |

2 (6.7%) |

3 (10.7%) |

0 |

0 |

| Asymptomatic |

4* |

2 (6.9%) |

1 (3.3%) |

0 |

2 (9.5%) |

1 (10.0%) |

| *Case with extensive hemorrhage and necrosis was excluded. Little sample size made the exact analysis testing of every number difficult.

To reduce the errors, we combined data of each group, and performed Pearson’s chi-square tests with correction for the continuity. |

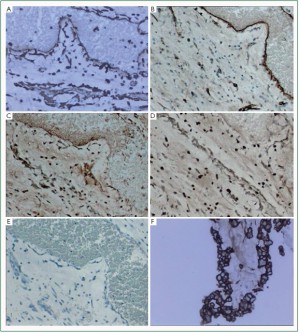

Immuohistochemical staining was carried out in 10 cases.

Vimentin was diffusely and strongly reactive with all tumor cells

and blood vessels, also reactive with surface lining cells. SMA,

CD34 and CD68 were expressed variably ( Figure 4, 5). Only

part of tumor cells showed positive immunoreactivity for these

antibodies. The surface lining cells were only positively stained

for Vimentin and CD34 ( Figure 4F). The glandular cells showed positive CK and EMA expressions ( Figure 3C, 3D). Recurrent myxomas

In our series, a 29-year-old male, who underwent a “biatrial and

right ventricular myxoma excision” operation at other institution

seven years ago (detailed operation and pathological information

at that time was hardly available), presented with a recurrent

tumor. He accepted a second surgery at our institution, and two

recurrent tumor masses which respectively located in the right

atrium and tricuspid valve were observed. Pathological analysis

showed the tumor masses have solid surface and rumentary

vessels, with foci of hemorrhage, hemorsiderin and patched

calcification, which were similar to other sporadic myxomas.

However, no pedicle was found. Although the patient denied

any family history, we still regard him as a familial myxoma case

according to the clinical features. A 16-year-old boy also bore

recurrence at the same place (the upper atrial septum) with a

pedicle (2 cm × 1.5 cm) after left myxoma resection two years

before. The patient presented in April 2006 with dyspnea and

palpitation over six months, and the tumor showed papillary

surface and single cell predominant structure. In May 2008 the

patient accepted the second surgery, however, the recurrent

tumor showed a solid appearance and cell cord predominant

arrangement structure. After that he recovered uneventfully.

We consider the recurrence may attribute to the residual tumor

cells. The other recurrent case was a 67-year-old female, who

present with dyspnea and palpitation, with a history of “left

atrial myxoma resection” twenty years before. The pathologic

examination revealed the tumor had a pedicle and appeared a

solid surface type and vasoformative ring predominant pattern.

Unfortunately, the previous excision record was not available.

The patient also recovered uneventfully after the second surgery.

Histologically, we found the recurrent cases had no malignant

histological characteristics, for instance, atypical nucleus and

pathologic karyokinesis.

|

|

Discussion

In the present study we have retrospectively reviewed a series

of 61 consecutive cardiac myxomas at a single institution of

Shandong Peninsula. To the best of our knowledge, this is one

of the largest populations related to myxomas during a decade’s

period. Our report is similar to the previous studies, which have

shown the tumors are the most common primary tumor, and

roughly 90% of the tumors are located in the atria, with the left

atrium accounting for 80% of those ( 18). Only 3-4% of myxomas

are detected in the left ventricle, and only 3-4% in the right ( 11).

Multilocular myxomas are extremely rare, which often result

in local recurrences ( 19). Familial myxomas are estimated to

account for 7% of atrial myxomas ( 20), are more often multiple,

recurrent and right sided, as compared to sporadic myxomas. The

affected patients are also younger, most presenting at 20-30 years

of age ( 21- 23). Moreover, our study demonstrated, for the first

time, that the surface appearance is associated with the tumor

cell arrangement structure. In addition, our study indicated that

the clinical presentations have no relations with the pathological

features, which may be different from the previous study ( 15).

The clinical presentation of myxomas is diverse and

dependent upon tumor location, size and mobility ( 24- 27).

According to a previous study, the most common symptom is

dyspnea (54%), and then followed by palpitation (35%) ( 15). Dyspnea and edema of lower limbs are thought to a consequence

of atrioventricular valve obstruction. Nevertheless, the intracardiac obstruction may also lead to narrowing outflow

tract and atrial fibrillation, which could contribute to dyspnea

and palpitation. Cough is thought to result in pulmonary venous

hypertension and frank pulmonary edema. Angina may be

caused by insufficient blood supply. Embolism is also a classic

symptom of myxomas, which have been reported to associate

with the papillary surface ( 15). The cause of some constitutional

disturbances is still unclear. Some findings suggest the cytokine

interleukin-6 (IL-6) may be responsible for that. The relationship

between IL-6 and constitutional syndromes is still controversial.

In some cases, the right atrial myxomas may induce pulmonary

hypertension because of embolism of tumor fragments. Right

ventricular myxomas may mimic stenosis of pulmonary valve

and cause syncope. In our series, both left and right atrial

myxomas were observed with symptoms of dyspnea, palpitation,

cough, and angina. Among them, one left atrial myxoma case

was observed with edema of lower limbs and syncope, however,

the patient also suffered from systemic lupus erythematosus

(SLE), which made the pathophysiological process even

puzzled. The symptoms disappeared after the myxoma resection.

Unfortunately, the patient died of SLE four years later. Besides,

two cases presented with cerebral infarction symptoms and one

case with angina and vertigo showed papillary surface, which was

consistent with previous studies ( 4, 15). However, in the present

study it is difficult to perform further exact analysis because of

the little sample size. Other cerebral symptoms in cases of solid

surface may only caused by cardiac obstruction and cerebral

ischemia. About 20% of cardiac myxomas are asymptomatic; they are

usually smaller than 4 cm ( 28, 29). The maximal diameter of four

asymptomatic cases of the present report was 6, 4, 3, and 3 cm,

respectively. We consider it is due to the small tumor size or long growth course, which may result in adaption to the tumor. In our study, 54.5% of patients exhibited abnormal

electrocardiography findings, compared with previous

study report of 56% ( 15). The abnormalities found on the

electrocardiography are usually nonspecific ( 11, 12, 15). They may

only reflect the hemodynamic alterations, such as atrial overload

or ventricular hypertrophy, which secondarily increased the

chamber diameter and altered conduction. Echocardiography is

widely recognized as a sensitive preoperative diagnostic method,

although it appears nonspecific to some occupying lesions. We

have an experience with a low grade cardiac myxofibrosarcoma,

which was considered as a myxoma on echocardiography.

Moreover, thrombus may be misdiagnosed as myxoma in some

cases. Nevertheless, echocardiography is also demonstrated as

the most accurate and reliable preoperative method with which

to predict the diameter, location, attachment, mobility, and

morphology of cardiac myxomas. Two surface types and three cell arrangement patterns

were observed in these cases. Statistical analysis revealed the

tumor cells of solid type have a tendency to form vasoforming

structures: the tumor cells may arranged in cords or rings.

However, the morphological features have no correlation

with the clinical presentations. The results indicate that the

morphologic classifications of cardiac myxomas may not be

significant for clinical practice. Imunohistochemical study

showed the tumor cells bear a diffuse, and positive expression

for Vimentin, and focal expressions for CD34, CD68, and

SMA. The results support the hypothesis of myxoma originated

from multipotential mesenchymal cells, capable of vessel,

smooth muscle, and histiocyte differentiation. The typical

mucous glands may represent rests of entrapped embryonic

foregut. Furthermore, previous reports have showed the cells

immunoreactive for neuropeptides (s-100, NSE) ( 7) and

Calrectinin ( 6, 30). Bone and brain metastases from glandular cardiac myxomas

have been reported in the recent literature ( 31- 35). The most

frequent metastatic site for cardiac myxomas is cerebrum ( 33).

Several reports have reviewed cerebral metastasis cases ( 34, 35).

Since most myxomas are located in the left atrium, systemic

embolism is particularly frequent. The tumor fragments

metastasized to cerebral vessel walls may penetrate through the

vessel wall, forming intra-atrial metastases. Some cytokines, such

as CXC chemokines, may explain the metastasis potential of

morphologically benign myxomas. In our series, no metastatic

case was observed, including two cases with typical mucous

glandular differentiation. Especially to deserve to be mentioned,

there was an uncommon histological likeness between the

glandular myxomas and mucinous adenocarcinomas. One case

with glandular differentiation in the series was considered as

metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma at one time. In conclusion, we have retrospectively reviewed a series of

61 myxoma cases at a single institution of Shandong Peninsula.

The clinical presentations and pathological characteristics

(particular on the relationship between the both) were

investigated. Myxomas may cause varies kinds of symptoms,

and mainly categorize into two surface subtypes and three

cell arrangement patterns. However, further statistical analysis

showed these morphological features have no relationship with

the clinical presentations. The results of this study indicate the

histopathologic classifications of cardiac myxomas may not be

significant for clinical practice. |

|

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Xiang-Rui Ji for his skillful assistance with

the English language.

Disclosure: We confirm that we have not previously published

or have not submitted the same manuscript elsewhere; we took

a significant part in the work and approved the final version of

the manuscript; we have complied with ethical standards; we

agree Pioneer Bioscience Publishing Company, to get a license

to publish the accepted article when the manuscript is accepted,

and we have obtained all necessary permissions to publish any

figures or tables in the manuscript, and assure that the authors

will pay for any necessary charges.

|

|

References

- Wold LE, Lie JT. Cardiac myxomas: a clinicopathologic profile. Am J Pathol

1980;101:219-40.

- Burke AP, Tazelaar H, Gomez-Roman JJ, et al. Cardiac myxoma. In: Travis

WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC, editors. Pathology

and Genetics of Tumours of the Lung, Pleura, Thymus and Heart. Lyon:

IARC Press, 2004: 260-3.

- Lie JT. The identity and histogenesis of cardiac myxomas: a controversy put

to rest. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1989;113:724-6.

- Burke AP, Virmani R. Cardiac myxoma. A clinicopathologic study. Am J

Clin Pathol 1993;100:671-80.

- Kodama H, Hirotani T, Suzuki Y, et al. Cardiomyogenic differentiation

in cardiac myxoma expressing lineage-specific transcription factors. Am J

Pathol 2002;161:381-9.

- Terracciano LM, Mhawech P, Suess K, et al. Calretinin as a marker for

cardiac myxoma. Diagnostic and histogenetic considerations. Am J Clin

Pathol 2000;114:754-9.

- Pucci A, Gagliardotto P, Zanini C, et al. Histopathologic and clinical

characterization of cardiac myxoma: review of 53 cases from a single

institution. Am Heart J 2000;140:134-8.

- Amano J, Kono T, Wada Y, et al. Cardiac myxoma: its origin and tumor

characteristics. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2003;9:215-21.

- Johansson L. Histogenesis of cardiac myxomas. An immunohistochemical

study of 19 cases, including one with glandular structures, and review of the

literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1989;113:735-41.

- Pucci A, Bartoloni G, Tessitore E, et al. Cytokeratin profile and

neuroendocrine cells in the glandular component of cardiac myxoma.

Virchows Arch 2003;443:618-24.

- Reynen K. Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1610-7.

- Butany J, Nair V, Naseemuddin A, et al. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and

management. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:219-28.

- St John Sutton MG, Mercier LA, Giuliani ER, et al. Atrial myxomas: a

review of clinical experience in 40 patients. Mayo Clin Proc 1980;55:371-6.

- Endo A, Ohtahara A, Kinugawa T, et al. Characteristics of cardiac myxoma

with constitutional signs: a multicenter study in Japan. Clin Cardiol

2002;25:367-70.

- Acebo E, Val-Bernal JF, Gómez-Román JJ, et al. Clinicopathologic study

and DNA analysis of 37 cardiac myxomas: a 28-year experience. Chest

2003;123:1379-85.

- Yokomuro H, Yoshihara K, Watanabe Y, et al. The variations in the

immunologic features and interleukin-6 levels for the surgical treatment of

cardiac myxomas. Surg Today 2007;37:750-3.

- Wang JG, Wei ZM, Liu H, et al. Primary pleomorphic liposarcoma of

pericardium. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010;11:325-7.

- Kumar BV, Abbas AK, Fausto N, et al. Cardiac tumors. In: Kumar BV,

Abbas AK, Fausto N, Mitchell R, editors. Robbins basic pathology, 8th

edition. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2007: 417-8.

- Martin LW, Wasserman AG, Goldstein H, et al. Multiple cardiac myxomas

with multiple recurrences: unusual presentation of a “benign” tumor. Ann

Thorac Surg 1987;44:77-8.

- Casey M, Mah C, Merliss AD, et al. Identification of a novel genetic

locus for familial cardiac myxomas and Carney complex. Circulation

1998;98:2560-6.

- Larsson S, Lepore V, Kennergren C. Atrial myxomas: results of 25 years’

experience and review of the literature. Surgery 1989;105:695-8.

- Edwards A, Bermudez C, Piwonka G, et al. Carney’s syndrome: complex

myxomas. Report of four cases and review of the literature. Cardiovasc Surg

2002;10:264-75.

- Papagiannopoulos K, Hughes S, Nicholson AG, et al. Cystic lung lesions

in the pediatric and adult population: surgical experience at the Brompton

Hospital. Ann Thorac Surg 2002;73:1594-8.

- Premaratne S, Hasaniya NW, Arakaki HY, et al. Atrial myxomas:

experiences with 35 patients in Hawaii. Am J Surg 1995;169:600-3.

- Bjessmo S, Ivert T. Cardiac myxoma: 40 years’ experience in 63 patients.

Ann Thorac Surg 1997;63:697-700.

- Pinede L, Duhaut P, Loire R. Clinical presentation of left atrial cardiac

myxoma. A series of 112 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore)

2001;80:159-72.

- Gabe ED, Rodríguez Correa C, Vigliano C, et al. [Cardiac myxoma.

Clinical-pathological correlation]. Rev Esp Cardiol 2002;55:505-13.

- Goswami KC, Shrivastava S, Bahl VK, et al. Cardiac myxomas: clinical and

echocardiographic profile. Int J Cardiol 1998;63:251-9.

- Grebenc ML, Rosado-de-Christenson ML, Green CE, et al. Cardiac

myxoma: imaging features in 83 patients. Radiographics 2002;22:673-89.

- Acebo E, Val-Bernal JF, Gómez-Roman JJ. Thrombomodulin, calretinin

and c-kit (CD117) expression in cardiac myxoma. Histol Histopathol

2001;16:1031-6.

- Moiyadi AV, Moiyadi AA, Sampath S, et al. Intracranial metastasis

from a glandular variant of atrial myxoma. Acta Neurochir (Wien)

2007;149:1157–62.

- Uppin SG, Jambhekar N, Puri A, et al. Bone metastasis of glandular cardiac

myxoma mimicking a metastatic carcinoma. Skeletal Radiol 2011;40:107-11.

- Shimono T, Makino S, Kanamori Y, et al. Left atrial myxomas. Using

gross anatomic tumor types to determine clinical features and coronary

angiographic findings. Chest 1995;107:674-9.

- Altundag MB, Ertas G, Ucer AR, et al. Brain metastasis of cardiac myxoma:

case report and review of the literature. J Neurooncol 2005;75:181-4.

- Rodrigues D, Matthews N, Scoones D, et al. Recurrent cerebral metastasis

from a cardiac myxoma: case report and review of literature. Br J Neurosurg

2006;20:318-20.

Cite this article as: Wang JG, Li YJ, Liu H, Li NN, Zhao J, Xing XM.

Clinicopathologic analysis of cardiac myxomas: Seven years’ experience

with 61 patients. J Thorac Dis 2012;4(3):272-283. doi: 10.3978/

j.issn.2072-1439.2012.05.07

|