2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病管理:中国专家共识(2024)

文章亮点

主要发现

• 2型(T2)炎症性呼吸系统疾病是一类以2型免疫反应为主要发病机制的炎症性疾病。在管理这类疾病时,需充分考量每种具体的2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病及其共病的特征,从而实现精准治疗,尤其是合理选用靶向2型炎症的生物制剂进行治疗。

推荐意见是什么,有哪些新进展?

•慢性呼吸系统疾病通常包括哮喘、慢性阻塞性肺疾病等一系列气道疾病。这些疾病具有高度异质性,其典型特征是涉及多种炎性细胞和介质浸润的慢性气道和肺部炎症。慢性呼吸系统疾病的药物治疗主要针对控制气道炎症(如吸入性糖皮质激素、白三烯受体拮抗剂)、扩张支气管(如长效β-2-受体激动剂、长效毒蕈碱拮抗剂)和缓解急性发作(如短效β受体激动剂、全身性糖皮质激素)。

• 2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病以2型炎症为主要特征,具体包括哮喘、部分慢性阻塞性肺疾病、过敏性支气管肺曲霉病、嗜酸性肉芽肿性多血管炎、嗜酸性粒细胞性支气管炎、嗜酸性粒细胞性肺炎以及部分非囊性纤维化支气管扩张。已有研究证实,针对2型炎症的疗法在治疗2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病及其共病方面疗效显著。

其中的含义是什么,现在应该改变什么?

• 2型炎症靶向疗法显示出对2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病及其共病的高效治疗作用,但目前尚缺乏高质量的研究对其临床效果进行评价。而且,需要进一步探索能够有效治疗所有2型炎症性疾病的生物制剂。

一、引言

2型(T2)炎症性呼吸系统疾病,是一系列由2型炎症介导、累计气道和肺组织的炎症性疾病。2型炎症是指一种特殊的免疫反应,涉及免疫系统中参与促进黏膜表面屏障免疫的固有免疫和适应性免疫部分[1]。这类疾病涵盖了哮喘、过敏性支气管肺曲霉病(allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis,ABPA)、嗜酸性肉芽肿性多血管炎(eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis,EGPA)、部分慢性阻塞性肺疾病(chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,COPD,简称“慢阻肺病”)和非囊性纤维化支气管扩张以及其他相关疾病。哮喘和慢阻肺病的全球患病率极高,而ABPA和EGPA的诊断和治疗给临床工作带来了巨大挑战。因此,深入理解其发病机制以实现精确干预显得尤为必要。

全球约有近10亿人受2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的影响[2-5]。全球确诊哮喘的患病率为4.3%[2],在中国20岁及以上人群中哮喘患病率为4.2%,患者人数超过4 500万人[6]。2015年,全球疾病负担(Global Burden of Disease,GBD)研究报告显示,全球哮喘年死亡人数约为40万;2019年,中国哮喘死亡人数约为2.5万[7]。全球慢阻肺病年死亡人数为320万[7],其中中国慢阻肺病患者年死亡人数为103.7万,约占全球的三分之一[8]。虽然中国哮喘和慢阻肺病的死亡率呈逐年下降趋势,但死亡人数随年龄增长而上升,疾病防控形势依然严峻[8]。此外,误诊和漏诊问题普遍存在,这加重了人们对这些疾病不良后果的担忧。我国一项研究显示,因哮喘就诊的患者中约2.5%为ABPA患者[9]。EGPA虽不常见,但可累及呼吸系统及全身多个组织和器官,导致医疗资源的大量消耗。研究表明,分别有17%~42%和25%~42%的EGPA患者需要经常住院和定期急诊就诊[5]。

2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病常与其他系统疾病合并存在。例如,哮喘常合并下呼吸道疾病,如ABPA和COPD、还可伴有过敏性鼻炎(allergic rhinitis,AR)、慢性鼻窦炎伴鼻息肉(chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps,CRSwNP)以及消化和皮肤等方面的疾患。与无这些共病的患者相比,共病的存在显著降低了患者的生活质量,加重了疾病的严重程度,同时也增加了医疗负担[10]。

近年来,国内外针对2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的发病机制、生物标志物和靶向治疗的研究成为热点,这促进了对2型炎症性疾病,特别是与过敏性和嗜酸性粒细胞性哮喘相关内容的更深入了解。然而,临床医生对该领域研究进展的临床意义认识不足,对靶向各种T2通路的生物制剂的临床应用仍缺乏了解。为指导临床医务工作者对这类疾病进行准确评估以及合理选择生物制剂治疗,中华医学会变态反应学分会呼吸过敏疾病学组(筹)组织了15位呼吸科或变态反应学专家进行深入讨论,并撰写了本共识报告。本共识有助于临床医师更全面、系统地认识2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的免疫应答、病理特征和临床表现。此外,在规范药物治疗的基础上,对重度难治性疾病的生物制剂治疗选择提供指导意见和合理的治疗策略。本共识将秉持不断更新、立足循证的疾病管理理念,在未来持续补充和完善。

二、方法

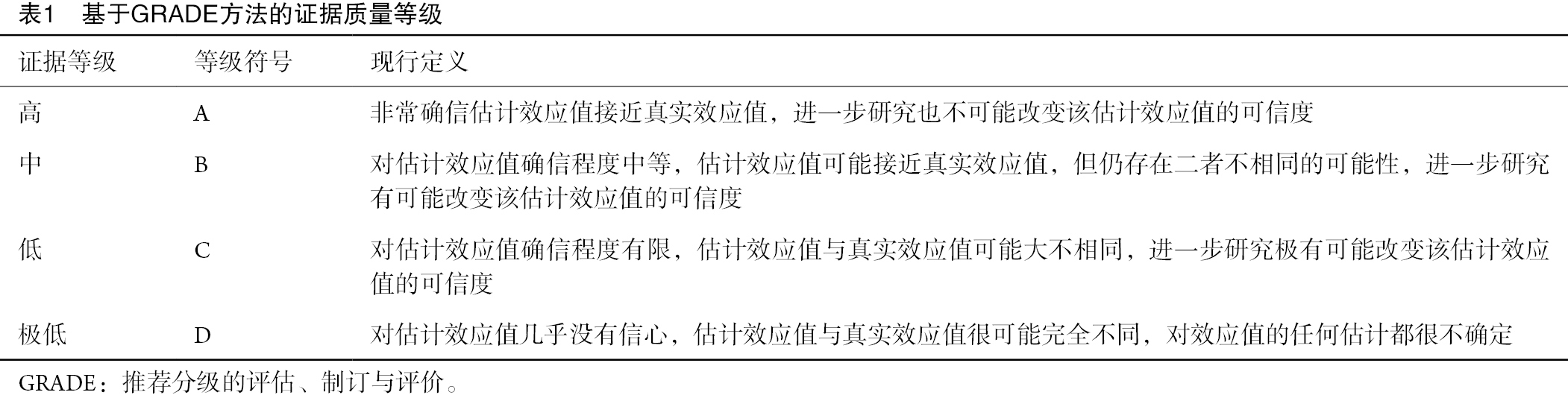

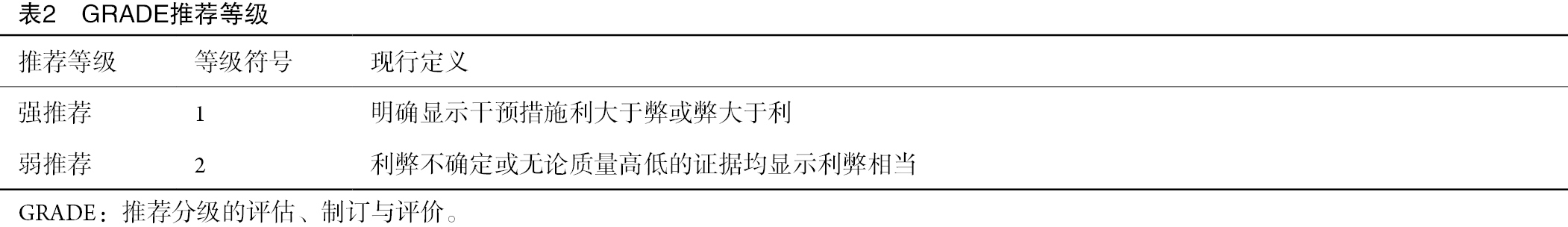

在本共识的制定过程中,设立了文献整理小组。该小组根据2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病相关问题制定了科学合理的检索策略。近10年发表的相关文献主要来源于PubMed平台,检索从国内外相关指南引用的支持依据的原始文献入手,随后逐步扩展检索和筛选范围,以纳入更广泛的文献。检索项目包括“((2型[标题/摘要])或(Th2[标题/摘要])或(ILC2[标题/摘要]))和((哮喘[标题/摘要])或(慢性鼻窦炎伴鼻息肉[标题/摘要])或(CRSwNP[标题/摘要])或(慢性鼻窦炎不伴鼻息肉[标题/摘要])或(CRSwNP[标题/摘要])或(过敏性鼻炎[标题/摘要])或(AR[标题/摘要])或(过敏性支气管肺曲霉病[标题/摘要])或(ABPA[标题/摘要])或(慢性阻塞性肺疾病[标题/摘要])或(COPD[标题/摘要])或(嗜酸性肉芽肿性多血管炎[标题/摘要])或(EGPA[标题/摘要])或(嗜酸细胞性支气管炎[标题/摘要])或(EB[标题/摘要])或(嗜酸性粒细胞性肺炎[标题/摘要])或(EP[标题/摘要])或(非囊性纤维化支气管扩张[标题/摘要]))和((奥马珠单抗[标题/摘要])或(度普利尤单抗[标题/摘要])或(美泊利珠单抗[标题/摘要])或(本瑞利珠单抗[标题/摘要])或(瑞利珠单抗[标题/摘要])或(特泽利尤单抗[标题/摘要]))”。推荐分级的评估、制订与评价(Grading of Recommendations Assessment,Development and Evaluation,GRADE)系统为评估证据质量和推荐强度分级提供了一个标准化的框架[11-12]。通过专家共识会议的方式达成共识。共识工作组多次召开会议,针对2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的重点关注问题进行了充分讨论。为促进决策过程,进行了2轮匿名投票表决。第一轮投票主要围绕免疫应答机制、病理生理和临床关注问题进行筛选。随后,根据全体专家的投票结果,再次组织讨论,对共识的关注问题进行删除和修正。第二轮投票中,所有专家参照GRADE网格,就推荐意见达成共识。投票规则明确规定:对于存在分歧的部分,推荐或反对某一干预措施至少需要获得50%的参与者认可,且持相反意见的参与者比例需低于20%,若未满足此项标准则不产生推荐意见。值得强调的是,一个推荐意见若被列为强推荐,需要得到至少70%的参与者认可[13](表1-表2)。

Full table

Full table

三、呼吸系统的2型免疫应答机制与生物标志物

(一)2型免疫应答与2型炎症

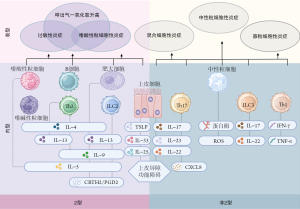

基于不同效应T细胞以及固有淋巴细胞(innate lymphoid cells,ILCs)的参与情况,免疫应答主要可分为3种类型:①由Th1细胞、ILC1、自然杀伤细胞(natural killer cell,NK)、CD8+ Tc1细胞和巨噬细胞介导的1型免疫应答;②由Th2细胞、ILC2和Tc2细胞介导的2型免疫应答;③由Th17细胞和ILC3介导的3型免疫应答。免疫应答除参与机体正常的保护作用外,1型和3型免疫应答主要与自身免疫性疾病相关,而2型免疫应答则主要参与过敏性疾病的发生发展[14-15]。

2型免疫应答主要由在Th2细胞和ILC2中表达的GATA- 3+转录因子驱动。在正常生理状态下,其对于抵御寄生虫感染及减轻炎症损伤至关重要[15]。上皮源性预警素类细胞因子,如胸腺基质淋巴细胞生成素(thymic stromal lymphoprotein,TSLP)、白细胞介素(interleukin,IL)-25和IL-33,能够启动或促进2型免疫应答,但其功能并不限于2型免疫应答[1]。过度的2型免疫应答可触发一系列炎症反应,即2型炎症。其典型特征是2型细胞因子,如IL-4、IL-5和IL-13的合成和释放增加,进而引起嗜酸性粒细胞(eosinophils,EOS)为主的组织浸润和免疫球蛋白E(immunoglobulin E,IgE)水平升高,最终导致一系列2型炎症性疾病[16]。已有研究报道,在部分哮喘、慢阻肺病及EGPA患者的支气管肺泡灌洗液或其他组织中,均检测到2型炎症因子表达升高,这表明这些疾病是由2型免疫应答介导的[16-23]。此外,2型免疫应答也参与了其他呼吸系统疾病,如ABPA、嗜酸细胞性支气管炎(eosinophilic bronchitis,EB)、嗜酸性粒细胞性肺炎(eosinophilic pneumonia,EP)及2型炎症性支气管扩张症。

(二)2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病机制

在2型炎症过程中,预警素可直接活化ILC2,刺激其产生IL-5、IL-13、IL-9等细胞因子。这些细胞因子可作用于多种细胞,包括嗜酸性粒细胞、嗜碱性粒细胞、肥大细胞和上皮细胞,从而促进2型炎症的发生[24]。同时,IL-13可促使活化的树突状细胞迁移到局部淋巴结,并与IL-4共同促进初始T细胞(naive T cell,Th0)分化为Th2细胞。Th2细胞会分泌IL-4、IL-5、IL-13等细胞因子。这些细胞因子与炎症细胞产生的嗜酸性粒细胞趋化因子如碳-碳基趋化因子11(CCL11)以及胸腺活化调节趋化因子(TARC/CCL17)协同作用,共同促进B细胞类别转换和IgE的产生。此外,它们还会将炎症细胞(包括嗜酸性粒细胞)募集到呼吸道和肺组织中。2型细胞因子还会诱导肥大细胞产生脂质介质,如前列腺素D2(prostaglandin D2,PGD2)。此外,进一步刺激ILC2向肺部迁移,最终促使2型细胞因子的持续生成,形成一种相互影响、协同作用的炎症回路[25-27](图1)。

(三)2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的病理生理

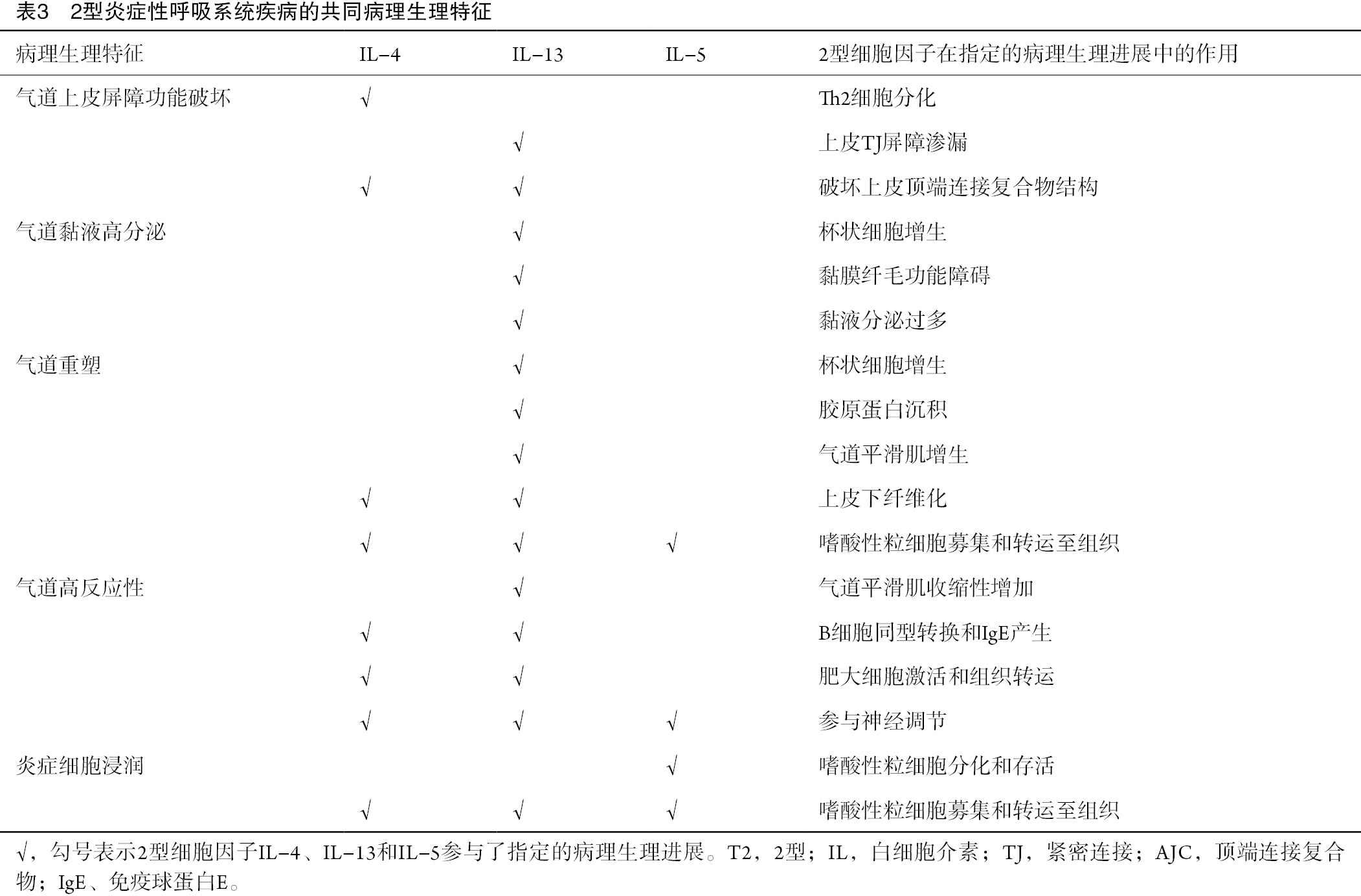

2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的主要病理生理特征包括气道上皮屏障功能破坏、炎症细胞浸润、气道黏液高分泌、气道重塑及气道高反应性(airway hyperreactivity,AHR)(表3)。T2细胞因子,特别是IL-4、IL-5和IL-13,在上述过程中发挥着关键作用。IL-4和IL-13可破坏上皮顶端连接复合物(epithelial apical junction complex,AJC)结构[28],而IL-13可导致支气管上皮紧密连接屏障出现渗漏[29]。此外,IL-4和IL-13可促进嗜酸性粒细胞募集到气道及肺组织。同时,IL-5可促进骨髓嗜酸性粒细胞前体细胞分化成熟,延长气道嗜酸性粒细胞存活,并激活释放白三烯(LT)和毒性颗粒蛋白,如嗜酸细胞阳离子蛋白(eosinophil cationic protein,ECP)、主要必需蛋白和嗜酸性粒细胞神经毒素[30]。IL-4和IL-13虽不会直接激活嗜酸性粒细胞,但会通过上调血管细胞粘附分子-1(粘附)和CC趋化因子受体3配体(迁移)的表达来促进嗜酸性粒细胞气道炎症[31]。

Full table

IL-13在促进杯状细胞黏液生成和气道重塑方面也至关重要[1]。IL-13可促进人支气管上皮细胞持续表达黏蛋白5AC(mucin 5AC,MUC5AC),导致黏液纤毛功能障碍,进而使气道黏液清除受阻,最终导致肺功能恶化[32-34]。IL-13不仅可导致上皮下胶原纤维沉积和杯状细胞增生,还可通过转移生长因子(transforming growth factor-β,TGF-β)信号通路诱导支气管上皮下纤维化[35-36]。此外,2型炎症因子可促进气道嗜酸性粒细胞浸润,嗜酸性粒细胞分泌TGF-β[37],刺激上皮细胞产生多种介质,促进气道平滑肌增殖[38],参与气道重塑[39]。

IL-4和IL-13还可诱导气道平滑肌收缩,进而导致气道狭窄和AHR形成[40-41]。Mas相关G蛋白偶联受体(Mas-related G-protein-coupled receptors,Mrgprs)表达的感觉神经元可被肥大细胞释放的神经肽FF激活,介导支气管平滑肌收缩和AHR[42-43]。此外,肺组织的感觉神经元可被IL-5激活从而释放血管活性肠肽,血管活性肠肽继而作用于CD4+ T淋巴细胞和ILC2,扩大炎症反应[44]。过敏原激发后,支气管收缩以及气道中嗜酸性粒细胞增多增强了感觉神经元引起咳嗽超敏反应的敏感性[45]。

推荐意见1

2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病包括哮喘、部分慢阻肺病、ABPA、EGPA、EB、EP和部分非囊性纤维化支气管扩张症(1D)。

推荐意见2

2型炎症反应主要由Th2细胞和ILC2及其分泌的IL-4、IL-5、IL-13等2型细胞因子介导。其引发的病理生理变化包括气道上皮屏障功能破坏、嗜酸性粒细胞浸润、气道黏液分泌过多、气道重塑和AHR(1D)。

(四)生物标志物

目前,呼吸系统疾病临床评估常用的2型炎症生物标志物包括血清总IgE(tIgE)、过敏原特异性IgE(sIgE)、痰EOS、血EOS和呼出气一氧化氮(FeNO)等。虽然全球哮喘防治创议(Global Initiative for Asthma,GINA)对2型炎症性哮喘进行了明确的定义,但对于其他2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的描述尚不明确[46]。

评估tIgE和sIgE水平对于诊断2型炎症性疾病和预测抗IgE抗体治疗的应答至关重要[47]。在过敏性哮喘患者中,常可观察到血清tIgE和sIgE水平升高[48-49]。其中,sIgE是判断过敏的主要标志物,而tIgE则是过敏性哮喘和ABPA进行抗IgE治疗的主要参考指标。此外,在慢阻肺病患者中,tIgE和sIgE水平升高与急性加重和肺功能下降相关[50]。值得注意的是,IgE的产生不仅是过敏的特征表现,还可见于寄生虫感染、多发性骨髓瘤和其他全身性疾病[51-52]。

血和气道EOS增多是2型炎症的主要特征之一。痰EOS≥3%可预测哮喘患者对吸入性糖皮质激素(inhaled corticosteroids,ICS)的反应性[53]。重度哮喘患者痰EOS增多(≥2%)与持续性气流受限相关,并且可预测哮喘控制不佳[54]。稳定期慢阻肺病患者痰EOS增多可预测未来急性加重风险增加,且与ICS治疗的良好反应性相关[55]。此外,有研究表明,痰EOS增多(≥2%)还与慢阻肺病患者肺功能下降及肺气肿严重程度显著相关[56]。

在哮喘患者中,血EOS计数与痰EOS之间存在相关性[57],这种相关性可用于预测哮喘急性发作和肺功能下降等不良结局[58-59]。自2019年起,GINA将血EOS计数≥150/μL作为诊断2型哮喘的标准之一[46],同时建议将其作为抗IL-5、抗IL-5R和抗IL-4R抗体治疗重度哮喘的生物标志物[46]。全球慢阻肺病防治创议(Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease,GOLD)建议将血EOS计数(≥300个细胞/μL)作为慢阻肺病患者ICS治疗的参考依据[60]。此外,在评估EOS计数升高时,必须排除寄生虫感染、肿瘤和风湿性免疫疾病等因素的影响。

FeNO是诊断2型哮喘的一种无创性生物标志物,具有简单、快速、重复性好等优点。GINA建议将FeNO水平≥20 ppb作为诊断2型哮喘的标准[46]。研究表明,FeNO水平超过47 ppb与气道嗜酸性粒细胞增多和激素反应相关,二者是哮喘急性发作的预测因素[61-62]。GINA推荐将FeNO作为预测抗IL-4R治疗应答的生物标志物[46]。此外,FeNO也是预测慢阻肺病气道嗜酸性粒细胞增多和糖皮质激素反应性的潜在生物标志物,且与慢阻肺病急性加重风险增加相关[63-64]。在预测重度慢阻肺病急性加重方面,FeNO比血液嗜酸性粒细胞计数更精确[65]。若将FeNO和血EOS这两个生物标志物联合应用,可进一步提高对中重度慢阻肺病急性加重的识别能力。

推荐意见3

血清tIgE、sIgE、血和痰EOS以及FeNO可用于评估2型炎症,并预测生物制剂的治疗反应。在开始和调整治疗策略之前,均应进行这些指标的检测(1D)。

推荐意见4

血清tIgE和血液嗜酸性粒细胞计数水平升高应排除寄生虫感染和/或其他相关疾病的潜在影响(1C)。

四、生物制剂治疗概述

针对2型炎症的生物制剂治疗,是针对2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病及其共病开展的精准治疗手段。该疗法能够特异性阻断或抑制这些疾病炎症通路中的靶分子,进而抑制相应通路所介导的炎症反应,从而最大限度地提高治疗的安全性。

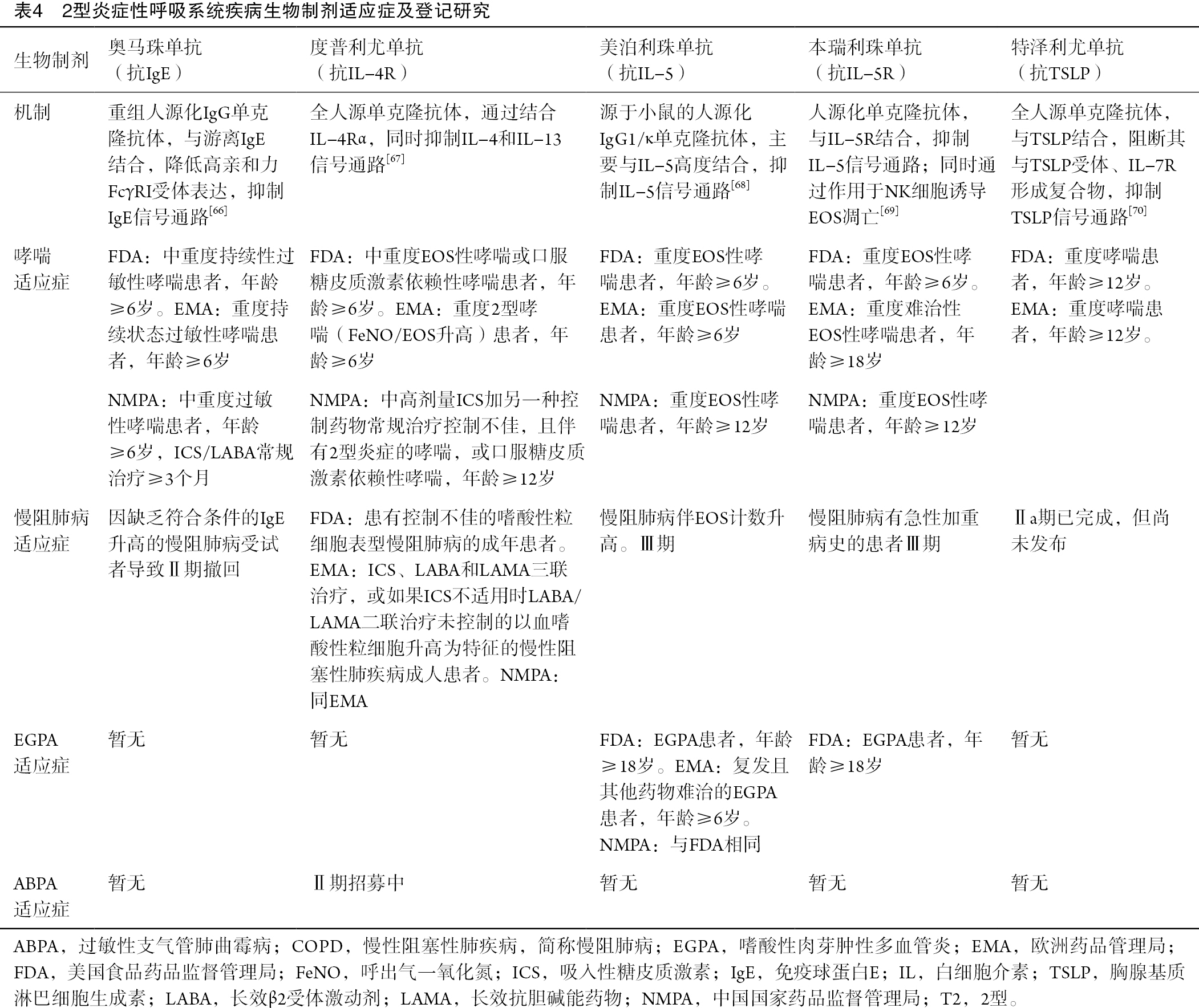

目前,中国国家药品监督管理局(China National Medical Products Administration,NMPA)、美国食品药品监督管理局(Food and Drug Administration,FDA)和欧洲药品管理局(European Medicines Agency,EMA)批准用于治疗哮喘和其他2型炎症性疾病的生物制剂治疗涵盖了多种类型,包括抗IgE抗体(奥马珠单抗)、抗IL-4受体α(抗-IL-4Rα)抗体(度普利尤单抗)、抗-IL-5抗体(美泊利珠单抗)和抗-IL-5受体抗体(本瑞利珠单抗)。FDA和EMA均已批准抗TSLP抗体(特泽利尤单抗),但NMPA尚未批准。这些生物制剂的具体获批情况、适应症及研究进展详见表4。

Full table

五、2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病

(一)哮喘

哮喘是一种以慢性气道炎症为主要特征的疾病,其临床表现为反复发作的喘息、气短、胸闷和咳嗽等症状,且这些症状在时间和强度尚存在变化,同时伴有可变性呼气性气流受限,部分患者气流受限可持续存在[46]。

作为一种复杂的异质性疾病,哮喘具有多种临床特征,由不同的潜在病理生理机制驱动。根据患者的免疫炎症特征,哮喘主要可分为两种内型:2型哮喘和非2型哮喘[66-71](图2)。根据炎症分类,2型哮喘包括过敏性哮喘、EOS性哮喘和其他混合性炎症内型/表型(表现为2型生物标志物升高,如FeNO)[71]。

目前,2型哮喘的确切患病率尚不明确。一项使用支气管镜刷检中2型相关转录物表达的病理学研究表明,约50%的轻中度哮喘病例可归类为2型哮喘[72]。在重度哮喘病例中,这种内型的患病率更高[18,73]。中国约56%~76%的成人重度哮喘及80%的儿童哮喘为2型哮喘[74-75]。

重度哮喘是指“需要使用高剂量ICS加第二种控制药物(和/或全身性糖皮质激素)治疗以防止其‘未控制’或尽管接受了该治疗仍‘未控制’的哮喘”[76]。未控制的哮喘需至少符合以下一项标准[77]:①症状控制不佳:哮喘控制问卷(ACQ)评分持续≥1.5,哮喘控制测试(Asthma Control Test,ACT)评分<20(或根据NAEPP/GINA指南确定为“控制不佳”);②频繁急性发作:过去一年内接受过≥2个疗程全身性糖皮质激素治疗(每次3 d);③重度急性发作:过去一年内至少一次住院、重症监护室(intensive care unit,ICU)住院或机械通气。

1. 2型炎症在哮喘中的作用与评估

2型哮喘由Th2细胞和ILC2共同驱动[78]。其详细机制和关键病理生理特征分别参见图1和表3。痰和血液中EOS、FeNO、血清IgE和等下游生物标志物水平升高也与这种哮喘内型相关[78]。

根据最新GINA报告,符合以下任何一项标准即可判定为2型哮喘[46]:①血EOS计数≥150/μL;②FeNO≥20 ppb;③痰EOS计数≥2%;④哮喘在临床上是过敏原驱动的。正在使用口服糖皮质激素(oral corticosteroid,OCS)的个体,应在重新检测血EOS计数、血清tIgE或sIgE和FeNO以进行重新评估之前,停止使用或维持最低剂量1~2周,因为OCS对这些标志物水平具有潜在的抑制作用。

2. 2型哮喘的生物制剂

通常,哮喘药物可分为控制药物和缓解药物。控制药物一般包括ICS、白三烯调节剂、吸入性长效β2受体激动剂(long-acting beta-2-agonists,LABA)、吸入性长效抗胆碱能药物(long-acting muscarinic anticholinergics,LAMA)、缓释茶碱或色甘酸钠。缓解药物通常包括吸入性速效β2受体激动剂、吸入性速效抗胆碱能药物、短效茶碱和全身性激素。最近,GINA 2024建议将低剂量ICS-福莫特罗作为维持和缓解治疗,而非仅按需使用[46]。此外,对于对中高剂量ICS/LABA治疗无反应的重度哮喘,LAMA和生物制剂是主要的额外治疗选择[79]。

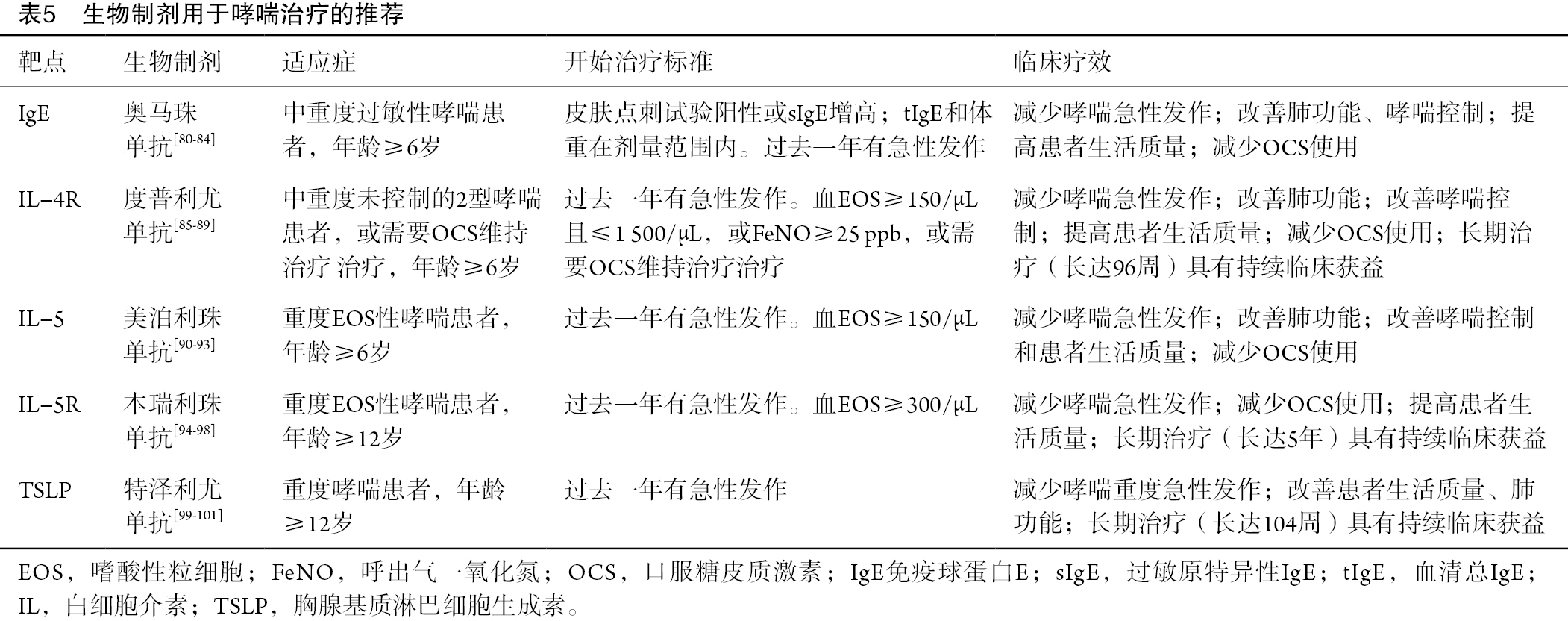

目前用于治疗2型哮喘的生物制剂包括奥马珠单抗、度普利尤单抗、美泊利珠单抗、本瑞利珠单抗和特泽利尤单抗[46]。多项Ⅲ期临床研究已证实,奥马珠单抗[80-84]、度普利尤单抗[85-89]、美泊利珠单抗[90-93]、本瑞利珠单抗[94-98]和特泽利尤单抗[99-101]在2型哮喘患者中能够减少急性发作、改善肺功能和哮喘控制,此外,还可提高患者的生活质量,且耐受性和安全性良好[46](表5)。

Full table

推荐意见5

对于未控制的中重度过敏性哮喘患者,推荐使用抗IgE(奥马珠单抗)作为附加治疗(1A)。

推荐意见6

对于中重度2型/EOS性哮喘,或需要OCS维持治疗的患者,推荐使用抗IL-4Rα(度普利尤单抗)作为附加治疗(1A)。

推荐意见7

对于重度EOS性哮喘患者,推荐使用抗IL-5/5Rα(美泊利珠单抗或本瑞利珠单抗)作为附加治疗(1A)。

推荐意见8

对于未控制的重度哮喘患者,推荐使用抗TSLP(特泽利尤单抗)作为附加治疗(1A)。

(二)慢阻肺病

慢阻肺病是一种异质性的肺部状态,其显著特征包含呼吸困难、咳嗽、咳痰和/或急性加重等慢性呼吸道症状,以及因气道异常(支气管炎、细支气管炎)和/或肺泡异常(肺气肿)所导致的持续性气流受限,且这种气流受限往往呈进行性[102]。若病情未得到有效控制,慢阻肺病可进一步发展为肺心病和呼吸衰竭,具有较高的致残率和病死率。慢阻肺病的发生是个体一生(T)中的基因(G)-环境(E)相互作用的结果[102],这种相互作用会损害肺部组织和/或改变其正常的发育/衰老过程。主要的致病暴露因素包括吸烟和吸入来自室内和室外环境的有毒颗粒和气体[102]。相关数据显示,在1990—2019年期间,全球204个国家和地区中,慢阻肺病所致的伤残调整寿命年有46.0%归因于吸烟[103]。2012—2015年,中国慢阻肺病吸烟暴露20包/年或以上的风险因素优势比为1.95[95%置信区间(CI):1.53~2.47][104]。

1. 2型炎症在慢阻肺病中的作用与评估

慢阻肺病的炎症反应存在多样性[105],其中约有高达40%的患者主要由2型炎症反应驱动[106]。当气道上皮细胞受到香烟烟雾、过敏原、细菌或病毒等有害刺激后,2型免疫应答被激活[107]。持续过强的炎症反应导致慢阻肺病的发生[107]。伴有2型炎症的慢阻肺病患者通常具有血EOS增多、FeNO升高、急性加重频率增加、吸入支气管舒张剂后可逆性更高以及哮喘样症状增加的特点[65,108]。但目前对于伴有2型炎症的慢阻肺病尚未形成尚未形成统一的诊断标准,多数研究以血和/或痰EOS升高为判断依据。持续性血EOS≥2%的慢阻肺病患者接近37%[109],持续性血EOS≥300/μL的患者约占15%~33%[106,109]。

2. 慢阻肺病的生物制剂

迄今为止,已有多种生物制剂在伴有2型炎症的慢阻肺病领域进行了探索,但仅抗IL-4Rα(度普利尤单抗)显示出了较为理想的治疗效果。两项Ⅲ期临床试验,即BOREAS研究[110]和NOTUS研究[111],探索了度普利尤单抗在伴有2型炎症(血EOS≥300个细胞/μL)且有相关急性加重史的中重度慢阻肺病患者中的疗效和安全性,目前这两项试验均已完成。研究结果表明,与安慰剂组相比,度普利尤单抗治疗52周可使中度或重度急性加重的年发生率分别降低30%和34%。此外,度普利尤单抗还显著改善患者第一秒用力呼气容积(FEV1)、症状和健康相关生活质量,且这些获益可持续至52周[110-111]。近期一项中国真实世界研究进一步证实,度普利尤单抗联合三联吸入疗法可增强伴有2型炎症的慢阻肺病患者的肺功能,缓解过敏症状,降低2型炎症生物标志物水平,改善患者的生活质量[112]。

另外,几项大型Ⅲ期研究探究了抗IL-5和抗IL-5R(如美泊利珠单抗和本瑞利珠单抗)在中重度慢阻肺病患者中的疗效[113-114]。然而,在EOS表型慢阻肺病患者中,与安慰剂相比,这两种生物制剂并未一致显示出可降低中度或重度急性加重年发生率的效果[113-114]。目前,抗上游预警素IL-33和TSLP的单克隆抗体(如Itepekimab、Tozorakimab、Astegolimab和特泽利尤单抗)在慢阻肺病患者中的疗效和安全性也正在研究当中[115-116]。

推荐意见9

对于接受ICS+LABA+LAMA治疗但仍有急性加重风险,且伴有2型炎症(如EOS≥300/μL)的未控制慢阻肺病患者,推荐加用抗IL-4Rα(度普利尤单抗)治疗(1A)。

(三)ABPA

ABPA是一种由烟曲霉(aspergillus fumigatus,AF)孢子定植于易感患者气道而引发的变应性肺部疾病。其临床主要表现为哮喘样症状和支气管扩张,肺部影像中常可见反复出现的游走性肺部阴影或黏液阻塞[117-118]。ABPA常常被误诊为支气管哮喘。回顾性研究显示,中国ABPA患者中93%有哮喘症状[119]。

1. 2型炎症在ABPA中的作用与评估

目前认为人体吸入真菌分生孢子后触发或诱发的2型免疫应答是ABPA的主要发病机制。其主要病理生理特征包括2型炎症细胞因子IL-4、IL-5和IL-13的生成增加,血清总IgE水平和烟曲霉sIgE、IgG合成增加,气道内杯状细胞化生和黏液沉积,肺部Th2细胞和EOS聚集等[120]。持续的炎症反应和组织破坏会导致支气管扩张,若病情继续发展,则会导致肺纤维化和呼吸衰竭[121]。

2型炎症生物标志物升高也是ABPA的重要诊断标准。其临界值为:血清烟曲霉sIgE≥0.35 kU/L、总IgE≥1 000 U/mL、EOS≥0.5×109/L[117]。近期一项中国研究发现,当烟曲霉sIgE的临界值为4.108 kU/L和EOS为0.815×109/L时,诊断效率最佳[122]。

2. ABPA的生物制剂

ABPA治疗的原则是控制炎症,最大限度地减少急性发作,降低真菌负荷和防止肺损伤的进展。目前,标准治疗为全身性糖皮质激素和抗真菌药物治疗。其中OCS是目前治疗ABPA的首选药物,ICS一般仅用于缓解ABPA患者的哮喘症状[117,121]。

据报道,生物制剂已成为ABPA的辅助治疗手段。近期进行的一项全面系统综述和荟萃分析,包括了评估奥马珠单抗、度普利尤单抗、美泊利珠单抗和本瑞利珠单抗4种生物制剂治疗ABPA疗效的所有现有研究[123]。在所有生物制剂中,奥马珠单抗相关研究最多。近年来,一项小规模随机对照研究(randomized controlled trial,RCT)显示,奥马珠单抗治疗ABPA可显著降低急性发作率和OCS剂量,并改善肺功能[124]。其他三种生物制剂的研究多为病例系列研究或病例报告,均显示对ABPA患者具有一定临床益处[123]。鉴于生物制剂用于ABPA患者的相关证据有限,其有效性及安全性仍有待进一步大规模RCT来验证。

推荐意见10

鉴于药物的可用性和可负担性,可将抗IgE(奥马珠单抗)作为ABPA的可选治疗方案(1B)。

(四)EGPA

EGPA是一种少见的可累及全身多个系统的自身免疫性疾病。其主要表现为血及组织中EOS增多、浸润,及中小血管的坏死性肉芽肿性炎症。除血清抗中性粒细胞胞浆抗体(serum antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies,ANCA)外,EOS在疾病发展中也起着至关重要的作用。几乎所有EGPA患者都有过敏背景,96%以上的患者存在哮喘和/或鼻窦炎。在疾病晚期,EGPA可累及全身多个组织器官[125-126]。

1. 2型炎症在EGPA中的作用与评估

EGPA的主要驱动因素是CD4+T细胞,尤其与Th2亚型有关。2型细胞因子(如IL-4、IL-5和IL-13)在EGPA引起的组织炎症反应中具有关键作用[126-127]。据估计,仅40%~60%的EGPA患者为ANCA阳性。ANCA阳性患者可能出现更多血管性疾病特征,如紫癜、神经病变、肺肾综合征;而ANCA阴性患者可能表现出更多EOS驱动症状,如肺部浸润和心肌病[127-128]。

2. EGPA的生物制剂

目前临床上常使用OCS和免疫抑制剂治疗EGPA。尽管OCS治疗可有效缓解症状,但在OCS减量或停药期间,EGPA容易复发[125]。随着生物制剂的广泛应用,多个研究表明针对2型炎症途径的治疗可能有效。Ⅲ期临床试验[129]证明,美泊利珠单抗与安慰剂相比,可提高EGPA疾病缓解率,降低复发率,并减少OCS的剂量,该药物已被FDA批准用于治疗EGPA。最近,一份循证指南建议在重度EGPA患者或无危及器官或危及生命症状的复发-难治性EGPA患者中,加用美泊利珠单抗联合糖皮质激素以维持疾病缓解[130]。一项观察性研究[131]表明,基于序贯利妥昔单抗(一种靶向CD20的单克隆抗体,一种在B细胞表面发现的蛋白)和美泊利珠单抗的治疗方案可能可有效诱导和维持全身和呼吸系统EGPA症状的缓解。一项回顾性队列研究表明,在实际临床实践中,本瑞利珠单抗可能是EGPA的有效治疗方法[132]。最近,一项头对头Ⅲ期试验(MANDARA)评估了本瑞利珠单抗与美泊利珠单抗相比的疗效和安全性,结果显示在复发性或难治性EGPA患者中,本瑞利珠单抗在诱导缓解方面非劣效于美泊利珠单抗[133]。

推荐意见11

对于正在接受免疫抑制治疗或正在接受低剂量口服糖皮质激素治疗且出现非重症复发的非重度EGPA患者,推荐添加美泊利珠单抗或本瑞利珠单抗作为联合治疗方案(1B)。

(五)EB

EB是引发慢性咳嗽的常见基础病因之一。接触粉尘、油烟等有害刺激常为咳嗽的诱因[134]。EB的主要表现为慢性咳嗽和痰中嗜酸性粒细胞增多,但通常无哮喘患者所常见的气道功能异常[135]。部分患者会合并AR[136]。在体格检查时,呼吸系统通常无显著异常;X线胸片和肺通气功能正常,支气管激发试验阴性[134]。

1. 2型炎症在EB中的作用与评估

EB是一种2型炎症驱动的疾病。除气道EOS增多外,对EB患者气道黏膜活检发现,T淋巴细胞、肥大细胞和ILC2水平同样增加,同时炎症介质和2型细胞因子水平升高(如组胺、LT、IL-4、IL-5和ECP等)。这些因素会引发气道黏液分泌、血浆渗出和炎症细胞浸润[137-138]。痰EOS计数≥2.5%是诊断EB的必要标准之一[139]。此外,FeNO水平≥32.5 ppb有助于在临床上诊断EB[140]。

2. EB的生物制剂

EB的主要治疗方法是抗炎治疗,临床上常使用ICS[141],很少需要长期使用OCS治疗[142]。Brightling等人曾报道过1例发生了与长期未受控制的嗜酸性粒细胞气道炎症相关的固定气流阻塞的EB患者[143]。也有学者推测,EB可能是哮喘表型发展的早期阶段[144]。目前,用于EB治疗的生物制剂仍处于临床试验阶段。美泊利珠单抗早期研究(NCT00292877)[145]已证实,其在控制EB部分临床症状方面有一定疗效,为EB的治疗开辟了新思路。但关于停药后EB的复发情况尚无数据结果,生物制剂的临床效果仍需更多长期研究做进一步评估。

推荐意见12

鉴于缺乏RCT研究证据以及真实世界研究有限(1D),目前不推荐对EB患者进行生物制剂治疗。

(六)EP

EP以肺实质或肺泡中大量EOS浸润为特征,分为急性EP(acute EP,AEP)和慢性EP(chronic EP,CEP)[146]。AEP起病急,常在几天到几周内发病。其主要临床表现为急性发热和呼吸困难,严重时可并发呼吸衰竭,肺部会快速出现阴影。多数AEP患者发病年龄在20岁左右,且与吸烟明显相关[147]。部分AEP患者的血EOS水平可能正常。若能早期诊断并及时治疗可使患者症状快速缓解,且极少复发[146-150]。CEP起病隐匿,呈慢性进行性发展,常见咳嗽、呼吸困难等症状,少见呼吸衰竭。大多数CEP患者发病年龄为30~50岁,且患者中吸烟者不到10%[149]。CEP患者早期血EOS可明显增多,近1/3患者可能会出现“肺水肿反转征”这一特异性影像学表现。约2/3的患者有过敏性哮喘史,对糖皮质激素反应良好,但易复发[150-151]。

1. 2型炎症在EP中的作用与评估

现有证据倾向于认为AEP是一种2型炎症相关性疾病。当吸入或暴露于烟草等抗原后,肺泡或上皮损伤激活炎症信号。这一过程可上调IL-33、IL-25和TSLP的分泌,从而激活2型炎症反应,并导致肺内EOS的活化和募集[146]。由于大多数AEP患者外周嗜酸性粒细胞无增多现象,因此详细的病史询问和计算机断层扫描图像有助于提示疑似AEP[146]。

2. EP的生物制剂

目前,OCS仍然是EP的主要治疗方法,通常适用于大多数患者,治疗持续时间一般为6~12个月[146]。然而,50%以上的CEP患者会复发,需再次进行OCS治疗[146]。考虑长期使用OCS可能导致严重不良反应,目前正在探索使用ICS和生物制剂治疗进行替代治疗。然而,这些替代治疗大多主要由病例报告作为支撑[152-153],缺乏确凿的证据。因此,需要进一步的RCT和真实世界研究来探索CEP生物制剂治疗的适应症、有效性和安全性。

推荐意见13

鉴于缺乏RCT研究证据以及真实世界研究有限(1D),目前不推荐对EP患者进行生物制剂治疗。

(七)非囊性纤维化支扩

非囊性纤维化支扩是由多种因素引起的反复发作的化脓性感染性疾病,可导致中小支气管反复损伤和/或阻塞,使支气管壁结构破坏,支气管出现持久性扩张。其临床表现包括慢性咳嗽、咳痰、间断咯血、伴或不伴呼吸困难或呼吸衰竭[154]。通常认为支扩是一种以中性粒细胞为主的慢性气道炎症性疾病,近年来,由于嗜酸性粒细胞参与其发病机制的可能性而受到关注。一项欧洲研究显示,约30%的患者痰EOS≥3%[155];另一项欧洲多队列研究[156]显示,22.6%的患者血EOS水平≥300/μL。将血EOS≥300/μL或FeNO≥25 ppb的嗜酸性粒细胞性支扩定义为2型炎症性支扩,大约31%的患者被归类为该亚型。此类患者通常呼吸困难更重,肺功能更差,生活质量更低[157]。

1. 2型炎症在非囊性纤维化支扩中的作用与评估

嗜酸性粒细胞性支扩患者通常表现出FeNO和痰IL-13水平升高,以及对支气管扩张剂的反应性增强[155]。支扩患者的血EOS≥300/μL与链球菌和假单胞菌感染有关[155]。铜绿假单胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa,PA)是一种常见的条件致病菌,可分泌氧化还原活性外毒素绿脓素,抑制Th1反应,促进Th2炎症反应。此外,PA分泌的毒素(如弹性蛋白酶B)可能通过激活上皮双调蛋白的表达促进2型炎症的发展[158-159]。这些发现提示2型炎症在支扩的发生发展中起一定作用。此外,以2型炎症增强为特征的多种疾病(如哮喘、ABPA、CRSwNP)常与支扩并存[159]。然而,2型炎症性支扩的统一诊断标准仍然未达成共识。

2. 非囊性纤维化支扩的生物制剂

生物制剂在支扩中的应用仍处于初步探索阶段。目前,正在评估多种2型炎症性生物制剂(奥马珠单抗、度普利尤单抗、美泊利珠单抗、本瑞利珠单抗和瑞利珠单抗)治疗支扩的潜在治疗获益。尽管多项病例报告和回顾性研究显示,上述生物制剂可减少哮喘合并支扩患者的哮喘急性发作次数,降低血和痰EOS计数,减少OCS用量或缩短OCS疗程,但这些结果有待进一步大型研究的确证[160-161]。具体而言,仅针对支扩的生物制剂治疗在当前研究中代表性不足,值得注意的是,正在进行中的MAHALE研究(NCT05006573)旨在探索本瑞利珠单抗治疗非囊性纤维化支扩的疗效,该研究结果尚未公布[162]。

初步结果表明,生物制剂治疗在支扩中具有一定的治疗前景,但存在几个障碍阻碍了其广泛应用。建立支扩相关气道炎症的标准化分类系统对于优化个体化治疗策略至关重要。目前缺乏这样的框架,使得难以选择最合适的治疗方法。此外,对支扩复杂发病机制的认识目前仍不深入,特别是对于有2型炎症倾向的这部分机制,还需进一步深入探索。

推荐意见14

鉴于缺乏RCT研究证据以及真实世界研究有限(1D),目前不推荐对非囊性纤维化支扩患者进行生物制剂治疗。

(八)与2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病相关的共病

1. 流行病学和机制

2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病常同时存在大量其他2型炎症性疾病,如哮喘、慢阻肺病、ABPA等下呼吸道疾病以及AR、CRSwNP等上呼吸道疾病、非甾体抗炎药(nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,NSAID)加重性呼吸道疾病(nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs(NSAID)-exacerbated respiratory disease,NERD)、阿司匹林加重性呼吸道疾病,以及非呼吸系统共病,如特应性皮炎(atopic dermatitis,AD)、嗜酸性食管炎(eosinophilic esophagitis,EOE)、眼部疾病、其他胃肠道疾病、食物过敏等[163]。对于2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病患者而言,存在共病的患者在症状表现、发作频率、住院时间和医疗费用等方面均明显高于无共病患者[164-165]。患者对OCS的依赖性增加,导致疾病负担明显加重[166-167]。调查显示,59%以上的患者患有两种以上的共病,无论严重程度如何,都显著降低了患者的生活质量[168]。大量证据表明,2型炎症在这些呼吸系统疾病中起着关键作用。患者可能表现出一种或多种2型炎症的临床特征,包括血清tIgE和sIgE水平升高,以及血或组织EOS增多等[1]。

2. 2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病共病的生物制剂

目前针对2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病共病的大型临床研究较少。大多数研究主要关注哮喘共病,例如,哮喘合并AR、CRSwNP、AD和慢阻肺病等。其中,针对哮喘共病CRSwNP的研究相对较多。哮喘共病CRSwNP的真实世界研究显示,奥马珠单抗、度普利尤单抗、美泊利珠单抗和本瑞利珠单抗可缓解哮喘和鼻部症状[169-173]。治疗4个月或6个月后,相关指标出现具有统计学显著性的变化[170-171]。此外,5项Ⅲ期研究的事后分析显示,度普利尤单抗在改善哮喘、鼻窦炎和AD症状方面具有显著效果[174]。该分析还提到,度普利尤单抗的改善作用迅速,并从治疗的前几个月一直持续到后续时间[174]。同样,关于哮喘共病AR,Ⅲ期研究的事后分析强调了度普利尤单抗在减少哮喘加重、增强肺功能和改善与鼻结膜炎相关的生活质量评分方面的有效性[175]。此外,关于哮喘共病慢阻肺病,一项单中心、回顾性研究显示,美泊利珠单抗在治疗6个月后可降低EOS水平、减少急性加重次数、降低OCS剂量并改善患者肺功能[176]。

阻断2型炎症介质的策略对多种2型炎症性疾病有良好疗效。特别是,奥马珠单抗已被证明对哮喘、CRSwNP和慢性自发性荨麻疹等疾病有效。另一方面,度普利尤单抗在哮喘、慢阻肺病、CRSwNP、AD和EOE中显示出治疗价值[177]。美泊利珠单抗和本瑞利珠单抗对哮喘、CRSwNP和EGPA等疾病均有效[129,170-171]。因此,在管理多系统2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病和非呼吸系统共病时,必须综合考虑不同系统的受累情况,以指导选择最合适的生物制剂。

3. 共病的多学科管理

管理2型炎症相关共病通常需要多学科方法。推荐实施多学科诊疗模式,以有效管理2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病共病,为患者制定个体化诊疗方案。多学科管理也有助于增加患者对疾病的理解、提高治疗的依从性和自我管理能力,并最终改善患者的生活质量。建立多学科护理团队能够确保以患者为中心,改善直接和间接治疗结果,降低医疗成本,并做出更合适的治疗决策[178-179]。中国的多学科管理模式以及未来的发展方向仍有待进一步摸索和完善(图3)。

推荐意见15

在治疗2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病时,建议根据患者的临床表现进行相关共病的多学科评估。评估内容包括评估共病、生物标志物、对生活质量的影响以及现有药物的使用情况(1D)。

推荐意见16

在选择2型炎症靶向治疗时,初始生物制剂应的首选应聚焦于对生活质量影响最严重的疾病并考虑获批适应症。应在治疗4~6个月后进行生物制剂的疗效评估(1A)。

六、展望

本共识是首个旨在指导中国临床医生治疗和管理2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的中国专家共识。尽管取得了一定进展,但目前可用的生物标志物仍存在局限性,且尚无一种生物制剂能够有效治愈所有2型炎症性疾病。然而,随着病理生理机制及治疗方法探索的不断深入,有望逐步研究出更多新型的生物标志物。这些新型标志物旨在进一步提高2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病的诊断准确性和管理水平。最近的研究已确定了2型炎症的几种潜在生物标志物,包括二肽基肽酶-4(dipeptidyl peptidase-4,DPP-4)、呼出气中的挥发性有机化合物、外周血ILC2的百分比和计数、ECP、嗜酸性粒细胞神经毒素(eosinophil derived neurotoxin,EDN)、CCL11和G蛋白偶联受体X2(mas-related G proteincoupled receptor X2,MRGPRX2)以及蛋白S的趋化因子或炎症介质[180-184]。此外,诱导痰中IL-4、IL-5和IL-13基因表达的RNA定量测定,也可能有助于更精准地识别2型炎症[18,185]。

目前,针对其他靶向2型炎症的生物制剂的研究正在进行中。这些生物制剂可能包括抗IL-9、抗IL-25、抗IL-33、抗TSLP、双特异性抗IL-13/TSLP[186]等抗体。特泽利尤单抗作为一种与TSLP结合的在研人IgG2单克隆抗体,已在北美和欧洲上市。其他类型的生物制剂包括前列腺素D2受体(DP2/CRTH2)拮抗剂、抗GATA C3抗体、JAK抑制剂、BTK抑制剂和抗OX40L抗体等[187-190]。鉴于2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病本质上属于系统性疾病,其主要驱动因素是持续异常的炎症细胞和炎症因子水平,因此2型炎症靶向制剂是否有可能替代目前基本的呼吸道治疗方案,成为主要的全身性治疗药物?此外,该类制剂是否能够应用于更广泛的轻中度患者人群,而非仅局限于重度患者?这些问题均有待进一步探索。但可以确定的事,个体化和精准化治疗必将成为该领域未来的发展方向。

七、结论

2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病以2型炎症为特征,主要包括哮喘、部分慢阻肺病、ABPA、EGPA、EB、EP和部分非囊性纤维化支扩。2型炎症靶向疗法在治疗2型炎症性呼吸系统疾病及其共病方面显示出较高的有效性。但目前尚缺乏高质量的研究对其临床效果进行全面、深入的评价。此外,需要研发能够有效治疗所有2型炎症性疾病的生物制剂。

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the below experts for their contribution to the consensus—Consultant in Chief: Prof. Nan Shan Zhong from the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. International Consultants: Prof. Kian Fan Chung from Imperial College London, United Kingdom; Professor Gary Wing-Kin Wong from Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China; Prof. Paul M. O’Byrne from McMaster University, Canada. Consultants: Prof. Yinshi Guo from the Department of Allergy, Renji Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Prof. Jie Shao from the Department of Pediatrics, Ruijin Hospital of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Prof. Limin Zhao from the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Henan Provincial People’s Hospital. Prof. Chun Chang from the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Peking University Third Hospital. Prof. Haijin Zhao from the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Nanfang Hospital of Southern Medical University. Prof. Chuangli Hao from the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Soochow University. Prof. Juntao Feng from the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xiangya Hospital of Central South University. Prof. Yuqing Wang from the Department of Respiratory Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Soochow University. Prof. Xinming Su from the Department of Respiratory Medicine, the First Hospital of China Medical University. Prof. Yadong Gao from the Department of Allergy, the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine. Methodology Consultant: Dr. Jiang Mei from the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University.

Footnote

Peer Review File: Available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-2092/prf

Funding: This work was supported by grants of

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://jtd.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/jtd-2024-2092/coif). R.C. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Journal of Thoracic Disease. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

References

- Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NM, et al. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016;15:35-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Papi A, Brightling C, Pedersen SE, et al. Asthma. Lancet 2018;391:783-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10:447-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Denning DW, Pleuvry A, Cole DC. Global burden of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis with asthma and its complication chronic pulmonary aspergillosis in adults. Med Mycol 2013;51:361-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jakes RW, Kwon N, Nordstrom B, et al. Burden of illness associated with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol 2021;40:4829-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Huang K, Yang T, Xu J, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and management of asthma in China: a national cross-sectional study. Lancet 2019;394:407-18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:691-706. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Long Z, Liu W, Qi J, et al. Mortality and Trend of Chronic Respiratory diseases in China from 1990 to 2019. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology 2022;43:14-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ma Y, Zhang W, Yu B, et al. Prevalence of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis in Chinese patients with bronchial asthma. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases 2011;34:909-13.

- Gómez de la Fuente E, Alobid I, Ojanguren I, et al. Addressing the unmet needs in patients with type 2 inflammatory diseases: when quality of life can make a difference. Front Allergy 2023;4:1296894. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:401-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an Emerging Consensus on Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. Chinese Journal of Evidence-based Medicine 2009;9:8-11.

- Jaeschke R, Guyatt GH, Dellinger P, et al. Use of GRADE grid to reach decisions on clinical practice guidelines when consensus is elusive. BMJ 2008;337:a744. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Annunziato F, Romagnani C, Romagnani S. The 3 major types of innate and adaptive cell-mediated effector immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:626-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chinese Society of Allergology. Wang L, Sun Y. Expert consensus on the mechanism and targeted therapy of type 2 inflammatory diseases. National Medical Journal of China 2022;102:3349-73.

- Martinez-Gonzalez I, Steer CA, Takei F. Lung ILC2s link innate and adaptive responses in allergic inflammation. Trends Immunol 2015;36:189-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Robinson D, Hamid Q, Bentley A, et al. Activation of CD4+ T cells, increased TH2-type cytokine mRNA expression, and eosinophil recruitment in bronchoalveolar lavage after allergen inhalation challenge in patients with atopic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1993;92:313-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters MC, Mekonnen ZK, Yuan S, et al. Measures of gene expression in sputum cells can identify TH2-high and TH2-low subtypes of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;133:388-94. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ying S, O'Connor B, Ratoff J, et al. Expression and cellular provenance of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and chemokines in patients with severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Immunol 2008;181:2790-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Byers DE, Alexander-Brett J, Patel AC, et al. Long-term IL-33-producing epithelial progenitor cells in chronic obstructive lung disease. J Clin Invest 2013;123:3967-82. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kim SW, Rhee CK, Kim KU, et al. Factors associated with plasma IL-33 levels in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017;12:395-402. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jakiela B, Szczeklik W, Plutecka H, et al. Increased production of IL-5 and dominant Th2-type response in airways of Churg-Strauss syndrome patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012;51:1887-93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dallos T, Heiland GR, Strehl J, et al. CCL17/thymus and activation-related chemokine in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:3496-503. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lloyd CM, Snelgrove RJ. Type 2 immunity: Expanding our view. Sci Immunol 2018;3:eaat1604.

- Halim TY, Steer CA, Mathä L, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells are critical for the initiation of adaptive T helper 2 cell-mediated allergic lung inflammation. Immunity 2014;40:425-35. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mortaz E, Amani S, Mumby S, et al. Role of Mast Cells and Type 2 Innate Lymphoid (ILC2) Cells in Lung Transplantation. J Immunol Res 2018;2018:2785971. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Jain A, Pasare C. Innate Control of Adaptive Immunity: Beyond the Three-Signal Paradigm. J Immunol 2017;198:3791-800. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Saatian B, Rezaee F, Desando S, et al. Interleukin-4 and interleukin-13 cause barrier dysfunction in human airway epithelial cells. Tissue Barriers 2013;1:e24333. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sugita K, Steer CA, Martinez-Gonzalez I, et al. Type 2 innate lymphoid cells disrupt bronchial epithelial barrier integrity by targeting tight junctions through IL-13 in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141:300-310.e11. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McBrien CN, Menzies-Gow A. The Biology of Eosinophils and Their Role in Asthma. Front Med (Lausanne) 2017;4:93. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nakagome K, Nagata M. The Possible Roles of IL-4/IL-13 in the Development of Eosinophil-Predominant Severe Asthma. Biomolecules 2024;14:546. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dunican EM, Elicker BM, Gierada DS, et al. Mucus plugs in patients with asthma linked to eosinophilia and airflow obstruction. J Clin Invest 2018;128:997-1009. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dunican EM, Elicker BM, Henry T, et al. Mucus Plugs and Emphysema in the Pathophysiology of Airflow Obstruction and Hypoxemia in Smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:957-68. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bonser LR, Zlock L, Finkbeiner W, et al. Epithelial tethering of MUC5AC-rich mucus impairs mucociliary transport in asthma. J Clin Invest 2016;126:2367-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee CG, Homer RJ, Zhu Z, et al. Interleukin-13 induces tissue fibrosis by selectively stimulating and activating transforming growth factor beta(1). J Exp Med 2001;194:809-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malavia NK, Mih JD, Raub CB, et al. IL-13 induces a bronchial epithelial phenotype that is profibrotic. Respir Res 2008;9:27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ohno I, Nitta Y, Yamauchi K, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF beta 1) gene expression by eosinophils in asthmatic airway inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 1996;15:404-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Halwani R, Vazquez-Tello A, Sumi Y, et al. Eosinophils induce airway smooth muscle cell proliferation. J Clin Immunol 2013;33:595-604. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pégorier S, Wagner LA, Gleich GJ, et al. Eosinophil-derived cationic proteins activate the synthesis of remodeling factors by airway epithelial cells. J Immunol 2006;177:4861-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Manson ML, Säfholm J, James A, et al. IL-13 and IL-4, but not IL-5 nor IL-17A, induce hyperresponsiveness in isolated human small airways. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020;145:808-817.e2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xiong DJP, Martin JG, Lauzon AM. Airway smooth muscle function in asthma. Front Physiol 2022;13:993406. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han L, Limjunyawong N, Ru F, et al. Mrgprs on vagal sensory neurons contribute to bronchoconstriction and airway hyper-responsiveness. Nat Neurosci 2018;21:324-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu Q, Tang Z, Surdenikova L, et al. Sensory neuron-specific GPCR Mrgprs are itch receptors mediating chloroquine-induced pruritus. Cell 2009;139:1353-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Talbot S, Abdulnour RE, Burkett PR, et al. Silencing Nociceptor Neurons Reduces Allergic Airway Inflammation. Neuron 2015;87:341-54. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Satia I, Watson R, Scime T, et al. Allergen challenge increases capsaicin-evoked cough responses in patients with allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;144:788-795.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2024. Updated May 2024. Available online: www.ginasthma.org

- Szefler SJ, Wenzel S, Brown R, et al. Asthma outcomes: biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129:S9-23. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burrows B, Martinez FD, Halonen M, et al. Association of asthma with serum IgE levels and skin-test reactivity to allergens. N Engl J Med 1989;320:271-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ahmad Al Obaidi AH, Mohamed Al Samarai AG, Yahya Al Samarai AK, et al. The predictive value of IgE as biomarker in asthma. J Asthma 2008;45:654-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lommatzsch M, Speer T, Herr C, et al. IgE is associated with exacerbations and lung function decline in COPD. Respir Res 2022;23:1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fitzsimmons CM, Falcone FH, Dunne DW. Helminth Allergens, Parasite-Specific IgE, and Its Protective Role in Human Immunity. Front Immunol 2014;5:61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nafría Jiménez B, Oliveros Conejero R. IgE multiple myeloma: detection and follow-up. Adv Lab Med 2022;3:79-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cowan DC, Taylor DR, Peterson LE, et al. Biomarker-based asthma phenotypes of corticosteroid response. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:877-883.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ten Brinke A, Zwinderman AH, Sterk PJ, et al. Factors associated with persistent airflow limitation in severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;164:744-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Singh D, Kolsum U, Brightling CE, et al. Eosinophilic inflammation in COPD: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1697-700. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hastie AT, Martinez FJ, Curtis JL, et al. Association of sputum and blood eosinophil concentrations with clinical measures of COPD severity: an analysis of the SPIROMICS cohort. Lancet Respir Med 2017;5:956-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ortega H, Katz L, Gunsoy N, et al. Blood eosinophil counts predict treatment response in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:825-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Semprini R, Williams M, Semprini A, et al. Type 2 Biomarkers and Prediction of Future Exacerbations and Lung Function Decline in Adult Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:1982-1988.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Backman H, Lindberg A, Hedman L, et al. FEV(1) decline in relation to blood eosinophils and neutrophils in a population-based asthma cohort. World Allergy Organ J 2020;13:100110. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agustí A, Celli BR, Criner GJ, et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Eur Respir J 2023;61:2300239. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Smith AD, Cowan JO, Brassett KP, et al. Exhaled nitric oxide: a predictor of steroid response. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:453-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kupczyk M, ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, et al. Frequent exacerbators--a distinct phenotype of severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 2014;44:212-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Maniscalco M, Fuschillo S, Mormile I, et al. Exhaled Nitric Oxide as Biomarker of Type 2 Diseases. Cells 2023;12:2518. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Xu X, Zhou L, Tong Z. The Relationship of Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide in Patients with AECOPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2023;18:3037-46. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alcázar-Navarrete B, Díaz-Lopez JM, García-Flores P, et al. T2 Biomarkers as Predictors of Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Arch Bronconeumol 2022;58:595-600. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pereira Santos MC, Campos Melo A, Caetano A, et al. Longitudinal study of the expression of FcεRI and IgE on basophils and dendritic cells in association with basophil function in two patients with severe allergic asthma treated with Omalizumab. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;47:38-40.

- Pelaia C, Vatrella A, Gallelli L, et al. Dupilumab for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2017;17:1565-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pelaia C, Vatrella A, Busceti MT, et al. Severe eosinophilic asthma: from the pathogenic role of interleukin-5 to the therapeutic action of mepolizumab. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:3137-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pelaia C, Vatrella A, Bruni A, et al. Benralizumab in the treatment of severe asthma: design, development and potential place in therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther 2018;12:619-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Marone G, Spadaro G, Braile M, et al. Tezepelumab: a novel biological therapy for the treatment of severe uncontrolled asthma. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2019;28:931-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kuruvilla ME, Lee FE, Lee GB. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2019;56:219-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:388-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Schleich F, Brusselle G, Louis R, et al. Heterogeneity of phenotypes in severe asthmatics. The Belgian Severe Asthma Registry (BSAR). Respir Med 2014;108:1723-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Deng Z, Jin M, Ou C, et al. Eligibility of C-BIOPRED severe asthma cohort for type-2 biologic therapies. Chin Med J (Engl) 2023;136:230-2. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Huang Y, Lin X, et al. Influence of degree of specific allergic sensitivity on severity of rhinitis and asthma in Chinese allergic patients. Respir Res 2011;12:95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung KF, Dixey P, Abubakar-Waziri H, et al. Characteristics, phenotypes, mechanisms and management of severe asthma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2022;135:1141-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J 2014;43:343-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Busse WW, Kraft M, Rabe KF, et al. Understanding the key issues in the treatment of uncontrolled persistent asthma with type 2 inflammation. Eur Respir J 2021;58:2003393. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asthma group of Chinese Throacic Society. Guidelines for bronchial asthma prevent and management(2020 edition) Asthma group of Chinese Throacic Society. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 2020;43:1023-48. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Busse W, Corren J, Lanier BQ, et al. Omalizumab, anti-IgE recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of severe allergic asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:184-90. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Solèr M, Matz J, Townley R, et al. The anti-IgE antibody omalizumab reduces exacerbations and steroid requirement in allergic asthmatics. Eur Respir J 2001;18:254-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Humbert M, Beasley R, Ayres J, et al. Benefits of omalizumab as add-on therapy in patients with severe persistent asthma who are inadequately controlled despite best available therapy (GINA 2002 step 4 treatment): INNOVATE. Allergy 2005;60:309-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lanier B, Bridges T, Kulus M, et al. Omalizumab for the treatment of exacerbations in children with inadequately controlled allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2009;124:1210-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Li J, Kang J, Wang C, et al. Omalizumab Improves Quality of Life and Asthma Control in Chinese Patients With Moderate to Severe Asthma: A Randomized Phase III Study. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2016;8:319-28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Castro M, Corren J, Pavord ID, et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Moderate-to-Severe Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2486-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Glucocorticoid-Dependent Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med 2018;378:2475-85. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bacharier LB, Maspero JF, Katelaris CH, et al. Dupilumab in Children with Uncontrolled Moderate-to-Severe Asthma. N Engl J Med 2021;385:2230-40. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wechsler ME, Ford LB, Maspero JF, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of dupilumab in patients with moderate-to-severe asthma (TRAVERSE): an open-label extension study. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10:11-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang Q, Zhong N, Fang H, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Patients from China with Persistent Asthma: A Subgroup Analysis of a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Parallel-Group, Phase 3 Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2023;207:A4768.

- Ortega HG, Liu MC, Pavord ID, et al. Mepolizumab treatment in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1198-207. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral glucocorticoid-sparing effect of mepolizumab in eosinophilic asthma. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1189-97. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khurana S, Brusselle GG, Bel EH, et al. Long-term Safety and Clinical Benefit of Mepolizumab in Patients With the Most Severe Eosinophilic Asthma: The COSMEX Study. Clin Ther 2019;41:2041-2056.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen R, Wei L, Dai Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of mepolizumab in a Chinese population with severe asthma: a phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. ERJ Open Res 2024;10:00750-2023. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016;388:2128-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Korn S, Bourdin A, Chupp G, et al. Integrated Safety and Efficacy Among Patients Receiving Benralizumab for Up to 5 Years. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9:4381-4392.e4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Harrison TW, Chanez P, Menzella F, et al. Onset of effect and impact on health-related quality of life, exacerbation rate, lung function, and nasal polyposis symptoms for patients with severe eosinophilic asthma treated with benralizumab (ANDHI): a randomised, controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:260-74. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menzies-Gow A, Gurnell M, Heaney LG, et al. Oral corticosteroid elimination via a personalised reduction algorithm in adults with severe, eosinophilic asthma treated with benralizumab (PONENTE): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm study. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10:47-58. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai K, Sun D, Dai R, et al. Benralizumab efficacy and safety in severe asthma: A randomized trial in Asia. Respir Med 2024; Epub ahead of print. [Crossref]

- Menzies-Gow A, Corren J, Bourdin A, et al. Tezepelumab in Adults and Adolescents with Severe, Uncontrolled Asthma. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1800-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wechsler ME, Menzies-Gow A, Brightling CE, et al. Evaluation of the oral corticosteroid-sparing effect of tezepelumab in adults with oral corticosteroid-dependent asthma (SOURCE): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10:650-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Menzies-Gow A, Wechsler ME, Brightling CE, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of tezepelumab in people with severe, uncontrolled asthma (DESTINATION): a randomised, placebo-controlled extension study. Lancet Respir Med 2023;11:425-38. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Evidence-based strategy document for COPD diagnosis, management, and prevention, with citations from the scientific literature. 2024 REPORT. 2024 GOLD Report - Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease – GOLD. Available online: https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/#:~:text=Evidence-based%20strategy%20document%20for%20COPD%20diagnosis%2C%20management%2C%20and,scientific%20literature.%20View%20the%202024%20Summary%20of%20Changes

- Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ 2022;378:e069679. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang C, Xu J, Yang L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in China (the China Pulmonary Health [CPH] study): a national cross-sectional study. Lancet 2018;391:1706-17.

- Expert Consensus on Immunomodulatory Therapy for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Writing Group. Expert consensus on immunomodulatory therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chinese General Practice 2022;25:2947-59.

- Halpin DMG, de Jong HJI, Carter V, et al. Distribution, Temporal Stability and Appropriateness of Therapy of Patients With COPD in the UK in Relation to GOLD 2019. EClinicalMedicine 2019;14:32-41. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lange P, Ahmed E, Lahmar ZM, et al. Natural history and mechanisms of COPD. Respirology 2021;26:298-321. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sharma V, Ricketts HC, Steffensen F, et al. Obesity affects type 2 biomarker levels in asthma. J Asthma 2023;60:385-92. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Casanova C, Celli BR, de-Torres JP, et al. Prevalence of persistent blood eosinophilia: relation to outcomes in patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 2017;50:1701162. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhatt SP, Rabe KF, Hanania NA, et al. Dupilumab for COPD with Type 2 Inflammation Indicated by Eosinophil Counts. N Engl J Med 2023;389:205-14. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bhatt SP, Rabe KF, Hanania NA, et al. Dupilumab for COPD with Blood Eosinophil Evidence of Type 2 Inflammation. N Engl J Med 2024;390:2274-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shi X, Tan CF, Chen XY, et al. Efficacy of dupilumab in the treatment of COPD with type 2 inflammation: A real-world study. Allergy Medicine 2024;2:100015.

- Criner GJ, Celli BR, Brightling CE, et al. Benralizumab for the Prevention of COPD Exacerbations. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1023-34. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavord ID, Chanez P, Criner GJ, et al. Mepolizumab for Eosinophilic Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1613-29. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rabe KF, Celli BR, Wechsler ME, et al. Safety and efficacy of itepekimab in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD: a genetic association study and randomised, double-blind, phase 2a trial. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:1288-98. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yousuf AJ, Mohammed S, Carr L, et al. Astegolimab, an anti-ST2, in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD-ST2OP): a phase 2a, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med 2022;10:469-77. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal R, Chakrabarti A, Shah A, et al. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: review of literature and proposal of new diagnostic and classification criteria. Clin Exp Allergy 2013;43:850-73. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asano K, Hebisawa A, Ishiguro T, et al. New clinical diagnostic criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis/mycosis and its validation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021;147:1261-1268.e5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeng Y, Xue X, Cai H, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis of Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Asthma Allergy 2022;15:53-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dietschmann A, Schruefer S, Krappmann S, et al. Th2 cells promote eosinophil-independent pathology in a murine model of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Eur J Immunol 2020;50:1044-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agarwal R, Muthu V, Sehgal IS, et al. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis. Clin Chest Med 2022;43:99-125. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen H, Zhang X, Zhu L, et al. Clinical and immunological characteristics of Aspergillus fumigatus-sensitized asthma and allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. Front Immunol 2022;13:939127. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen X, Zhi H, Wang X, et al. Efficacy of Biologics in Patients with Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lung 2024;202:367-83. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Voskamp AL, Gillman A, Symons K, et al. Clinical efficacy and immunologic effects of omalizumab in allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2015;3:192-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Multidisciplinary Expert Consensus Writing Group on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Eosinophilic Granulomatis with Poyangiitis. Multidisciplinary expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiration 2018;41:8.

- Kouverianos I, Angelopoulos A, Daoussis D. The role of anti-eosinophilic therapies in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int 2023;43:1245-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gleich GJ, Adolphson CR. The eosinophilic leukocyte: structure and function. Adv Immunol 1986;39:177-253. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Milne ME, Kimball J, Tarrant TK, et al. The Role of T Helper Type 2 (Th2) Cytokines in the Pathogenesis of Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis (eGPA): an Illustrative Case and Discussion. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2022;22:141-50. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Steinfeld J, Bradford ES, Brown J, et al. Evaluation of clinical benefit from treatment with mepolizumab for patients with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019;143:2170-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wechsler ME, Akuthota P, Jayne D, et al. Mepolizumab or Placebo for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:1921-32. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bettiol A, Urban ML, Bello F, et al. Sequential rituximab and mepolizumab in eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA): a European multicentre observational study. Ann Rheum Dis 2022;81:1769-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bettiol A, Urban ML, Padoan R, et al. Benralizumab for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol 2023;5:e707-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wechsler ME, Nair P, Terrier B, et al. Benralizumab versus Mepolizumab for Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. N Engl J Med 2024;390:911-21. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cai C. Unmasking nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis as an important cause of chronic cough. Medical Journal of Chinese People's Liberation Army 2014;39:365-8.

- Brightling CE, Ward R, Goh KL, et al. Eosinophilic bronchitis is an important cause of chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1999;160:406-10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai K, Chen R, Peng W, et al. Non-asthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis and its relationship with asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2017;47:66-71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhan C, Xu R, Li B, et al. Eosinophil Progenitors in Patients With Non-Asthmatic Eosinophilic Bronchitis, Eosinophilic Asthma, and Normal Controls. Front Immunol 2022;13:737968. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhan C, Liu J, Li B, et al. Group 2 innate lymphoid cells in patients with nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis. Allergy 2022;77:649-52. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhan W, Lai K. Research progress of eosinophilic bronchitis. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiration 2023;46:192-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu X, Wang X, Yao X, et al. Value of Exhaled Nitric Oxide and FEF(25-75) in Identifying Factors Associated With Chronic Cough in Allergic Rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019;11:830-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Berry MA, Hargadon B, McKenna S, et al. Observational study of the natural history of eosinophilic bronchitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2005;35:598-601. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gonlugur U, Gonlugur TE. Eosinophilic bronchitis without asthma. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2008;147:1-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Brightling CE, Woltmann G, Wardlaw AJ, et al. Development of irreversible airflow obstruction in a patient with eosinophilic bronchitis without asthma. Eur Respir J 1999;14:1228-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cockcroft DW. Eosinophilic bronchitis as a cause of cough. Chest 2000;118:277. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Mepolizumab: 240563, anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody - GlaxoSmithKline, anti-interleukin-5 monoclonal antibody - GlaxoSmithKline, SB 240563. Drugs R D 2008;9:125-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Suzuki Y, Suda T. Eosinophilic pneumonia: A review of the previous literature, causes, diagnosis, and management. Allergol Int 2019;68:413-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shorr AF, Scoville SL, Cersovsky SB, et al. Acute eosinophilic pneumonia among US Military personnel deployed in or near Iraq. JAMA 2004;292:2997-3005. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- De Giacomi F, Vassallo R, Yi ES, et al. Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia. Causes, Diagnosis, and Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;197:728-36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang J, Cai H. Research Progress on Acute Eosinophilic Pneumonia. Chinese Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care 2015;14:4.

- Allen J, Wert M. Eosinophilic Pneumonias. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:1455-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Gong H, Gao J. Clinical Analysis of 40 Patients with Eosinophilic Lung Diseases in Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Acta Academiae Medicinae Sinicae 2018;40:170-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lin RY, Santiago TP, Patel NM. Favorable response to asthma-dosed subcutaneous mepolizumab in eosinophilic pneumonia. J Asthma 2019;56:1193-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- To M, Kono Y, Yamawaki S, et al. A case of chronic eosinophilic pneumonia successfully treated with mepolizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6:1746-1748.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Bronchiectasis Expert Consensus Writing Collaboration Group. Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of bronchiectasis in adults in China. Chinese Journal of Tuberculosis and Respiration 2021;44:11.

- Tsikrika S, Dimakou K, Papaioannou AI, et al. The role of non-invasive modalities for assessing inflammation in patients with non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Cytokine 2017;99:281-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shoemark A, Shteinberg M, De Soyza A, et al. Characterization of Eosinophilic Bronchiectasis: A European Multicohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022;205:894-902. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Oriano M, Gramegna A, Amati F, et al. T2-High Endotype and Response to Biological Treatments in Patients with Bronchiectasis. Biomedicines 2021;9:772. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Agaronyan K, Sharma L, Vaidyanathan B, et al. Tissue remodeling by an opportunistic pathogen triggers allergic inflammation. Immunity 2022;55:895-911.e10. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guan WJ, Oscullo G, He MZ, et al. Significance and Potential Role of Eosinophils in Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023;11:1089-99. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Crimi C, Campisi R, Cacopardo G, et al. Real-life effectiveness of mepolizumab in patients with severe refractory eosinophilic asthma and multiple comorbidities. World Allergy Organ J 2020;13:100462. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kudlaty E, Patel GB, Prickett ML, et al. Efficacy of type 2-targeted biologics in patients with asthma and bronchiectasis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2021;126:302-4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Record History | ver. 5: 2021-11-16 | NCT05006573 | ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05006573

- Maspero J, Adir Y, Al-Ahmad M, et al. Type 2 inflammation in asthma and other airway diseases. ERJ Open Res 2022;8:00576-2021. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- ten Brinke A, Grootendorst DC, Schmidt JT, et al. Chronic sinusitis in severe asthma is related to sputum eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;109:621-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yawn BP, Yunginger JW, Wollan PC, et al. Allergic rhinitis in Rochester, Minnesota residents with asthma: frequency and impact on health care charges. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103:54-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Khan A, Vandeplas G, Huynh TMT, et al. The Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GALEN rhinosinusitis cohort: a large European cross-sectional study of chronic rhinosinusitis patients with and without nasal polyps. Rhinology 2019;57:32-42. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters AT, Bengtson LGS, Chung Y, et al. Clinical and economic burden of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis: A U.S. administrative claims analysis. Allergy Asthma Proc 2022;43:435-45. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McDonald VM, Osadnik CR, Gibson PG. Treatable traits in acute exacerbations of chronic airway diseases. Chron Respir Dis 2019;16:1479973119867954. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Armengot-Carceller M, Gómez-Gómez MJ, García-Navalón C, et al. Effects of Omalizumab Treatment in Patients With Recalcitrant Nasal Polyposis and Mild Asthma: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2021;35:516-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gallo S, Castelnuovo P, Spirito L, et al. Mepolizumab Improves Outcomes of Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps in Severe Asthmatic Patients: A Multicentric Real-Life Study. J Pers Med 2022;12:1304. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Detoraki A, Tremante E, D'Amato M, et al. Mepolizumab improves sino-nasal symptoms and asthma control in severe eosinophilic asthma patients with chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps: a 12-month real-life study. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2021;15:17534666211009398. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Domínguez-Sosa MS, Cabrera-Ramírez MS, Marrero-Ramos MDC, et al. Efficacy of dupilumab on chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps and concomitant asthma in biologic-naive and biologic-pretreated patients. Ann Med 2024;56:2411018. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nolasco S, Crimi C, Pelaia C, et al. Benralizumab Effectiveness in Severe Eosinophilic Asthma with and without Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps: A Real-World Multicenter Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021;9:4371-4380.e4. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Canonica GW, Bourdin A, Peters AT, et al. Dupilumab Demonstrates Rapid Onset of Response Across Three Type 2 Inflammatory Diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022;10:1515-26. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Busse WW, Maspero JF, Lu Y, et al. Efficacy of dupilumab on clinical outcomes in patients with asthma and perennial allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2020;125:565-576.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Isoyama S, Ishikawa N, Hamai K, et al. Efficacy of mepolizumab in elderly patients with severe asthma and overlapping COPD in real-world settings: A retrospective observational study. Respir Investig 2021;59:478-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Dellon ES, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, et al. Dupilumab in Adults and Adolescents with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. N Engl J Med 2022;387:2317-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Senna G, Micheletto C, Piacentini G, et al. Multidisciplinary management of type 2 inflammatory diseases. Multidiscip Respir Med 2022;17:813. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Vassilopoulou E, Skypala I, Feketea G, et al. A multi-disciplinary approach to the diagnosis and management of allergic diseases: An EAACI Task Force. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2022;33:e13692. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shiobara T, Chibana K, Watanabe T, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 is highly expressed in bronchial epithelial cells of untreated asthma and it increases cell proliferation along with fibronectin production in airway constitutive cells. Respir Res 2016;17:28. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Malinovschi A, Rydell N, Fujisawa T, et al. Clinical Potential of Eosinophil-Derived Neurotoxin in Asthma Management. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023;11:750-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pavord ID, Afzalnia S, Menzies-Gow A, et al. The current and future role of biomarkers in type 2 cytokine-mediated asthma management. Clin Exp Allergy 2017;47:148-60. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Ogulur I, Pat Y, Ardicli O, et al. Advances and highlights in biomarkers of allergic diseases. Allergy 2021;76:3659-86. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- An J, Lee JH, Won HK, et al. Clinical significance of serum MRGPRX2 as a new biomarker in allergic asthma. Allergy 2020;75:959-62. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Peters MC, Nguyen ML, Dunican EM. Biomarkers of Airway Type-2 Inflammation and Integrating Complex Phenotypes to Endotypes in Asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2016;16:71. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rogliani P, Manzetti GM, Bettin FR, et al. Investigational thymic stromal lymphopoietin inhibitors for the treatment of asthma: a systematic review. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2024;33:39-49. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Santus P, Saad M, Damiani G, et al. Current and future targeted therapies for severe asthma: Managing treatment with biologics based on phenotypes and biomarkers. Pharmacol Res 2019;146:104296. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Matucci A, Vivarelli E, Nencini F, et al. Strategies Targeting Type 2 Inflammation: From Monoclonal Antibodies to JAK-Inhibitors. Biomedicines 2021;9:1497. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zarrin AA, Bao K, Lupardus P, et al. Kinase inhibition in autoimmunity and inflammation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021;20:39-63. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Song R, Zhang H, Liang Z. Research progress in OX40/OX40L in allergic diseases. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2024;14:1921-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

(本译文仅供学术交流,实际内容请以英文原文为准。)